“I never, never want to be a pioneer… It’s always best to come in second, when you can look at all the mistakes the pioneers made — and then take advantage of them.”— Seymour Cray

About a year ago I attended a wonderful event in San Diego. This event was the JRV symposium (http://dept.ku.edu/~cfdku/JRV.html) organized by Z. J. Wang of Kansas State University. The symposium was a wonderful celebration of the careers of three giants of CFD, Bram Van Leer, Phil Roe and Tony Jameson who helped create the current state of the art. All three have had a massive influence on modern CFD with a concentration in aerospace engineering. Like most things, their contributions were based on a foundation provided by those who preceded them. It is the story of those pioneers that needs telling lest it be forgotten. It turns out that scientists are terrible historians and the origins of CFD are messy and poorly documented. See Wikipedia for example, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computational_fluid_dynamics, this history is appallingly incomplete.

I wanted to make a contribution, and with some prodding Z. J. agreed. I ended up giving the last talk of the symposium titled “CFD Before CFD” (http://dept.ku.edu/~cfdku/JRV/Rider.pdf). As it turned out the circumstances for my talk became more trying. Right before my talk Bram Van Leer delivered what he announced would probably be his last scientific talk. The talk turned out to be a fascinating history of the development of Riemann solvers in the early 1980’s. In addition, it was a scathing condemnation of the lack of care some researchers take in understanding and properly citing the literature. It was a stunningly hard act to follow.

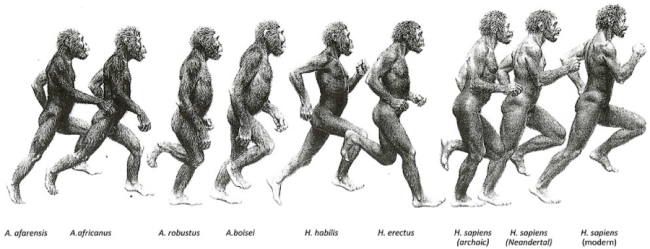

In talking about the history of CFD, I used the picture of the accent of man to illustrate the period of time. Part I of the history would correspond to the emergence of man from the forests of Africa to the savannas where apes become Australopithecus, but before the emergence of the genus Homo. The history of man before man!

The talk was a look at the origins of CFD that occurred at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project in World War II. Part of the inspiration for the talk was a lecture Bram gave a couple years prior called the “History of CFD: Part II”. As I discovered during a discussion with Bram, there is no Part I. With the material available on the origins of CFD so sketchy, incomplete and wrong, it is something I need to work to rectify. First of all, it wasn’t called CFD until 1967 (this term was invented by C.K. Chu of Columbia University) although the term rapidly gained acceptance with Pat Roache’s book of the same title probably putting the term “over the top”.

So, I’m probably committed to giving a talk titled the “History of CFD: Part I”. The talk last summer was a down payment. History is important to study because it contains many lessons and objective experience that we might learn from. The invention of CFD was almost certainty properly placed in 1944 Los Alamos during World War II. It is probably appropriate that the first operational use of electronic computers coincides with the first CFD. It isn’t well known that Hans Bethe and Richard Feynman two Nobel Prize winners in physics executed the first calculations! Really they led a team of people pursuing calculations supporting the atomic bomb work at Los Alamos. Feynman executed the herculean task of producing the first truly machine calculations. Prior to this calculators were generally people (women primarily) who produced the operations with the assistance of mechanical calculators. Bethe led the “physics” part of the calculation which used two methods for numerical integrations: one invented by Von Neumann based on shock capturing, and a second developed by Rudolf Peierls based on shock tracking. Von Neumann’s method was ultimately unsuccessful because Richtmyer hadn’t invented the artificial viscosity, yet. Without dissipation at the shock waves, Von Neumann’s method eventually explodes into oscillations, and become functionally useless.

CFD continued to be invented at Los Alamos after the war as the Cold War unfolded. The invention of artificial viscosity happened during the postwar work at Los Alamos where the focus had shifted to the hydrogen bomb. Computation was a key to continued progress. For example, the Monte Carlo method was an invention there in that period. First with the invention of useful shock capturing schemes by Richtmyer (building on Von Neumann’s work from 1944) in 1948. This was closely followed by seminal work by Peter Lax (started during his brief time on staff at Los Alamos in 1949-1950 plus summers there for more than a decade), and Frank Harlow in 1952. These three bodies of work formed the foundation for CFD that Van Leer, Jameson and Roe among others built on.

My sense was that once Richtmyer showed how to make shock capturing methods work, Lax and Harlow were able to proceed with great confidence. Knowing something is possible has the incredible effect of assuring that efforts can be redoubled with assurance of success. When you haven’t seen a demonstration of success, problems along the way are much more difficult to overcome.

Like so many innovations made there, the chief developments for the long term did not continue to be centered in Los Alamos, but spread outward to the rest of the World. This is  common and not unlike other innovations such as the Internet (started by DoD/DARPA but perfected outside the defense industry). While Los Alamos was a hotbed of development for CFD methods, over time, it ceased to be the source of innovation. This state of affairs was a constant source of consternation on my part while I worked at the Lab. Ultimately computation had a very utilitarian role there, and once they were functional, innovation wasn’t necessary.

common and not unlike other innovations such as the Internet (started by DoD/DARPA but perfected outside the defense industry). While Los Alamos was a hotbed of development for CFD methods, over time, it ceased to be the source of innovation. This state of affairs was a constant source of consternation on my part while I worked at the Lab. Ultimately computation had a very utilitarian role there, and once they were functional, innovation wasn’t necessary.

Rumor has it that Harlow was nearly fired in his early time at Los Alamos because the value of his work was not appreciated. Fortunately another senior person came to Frank’s defense and his work continued. Indeed my experience at Los Alamos showed a prevailing culture that didn’t always appreciate computation as a noble or even useful practice. Instead it was viewed with suspicion and distrust, an unfortunate necessity of work. It is a rather sad commentary on how inventions fail to be appreciated by the place where they took place.

Harlow’s efforts formed the foundation of engineering CFD in many ways. The basic methods and philosophy inspired scientists the world over. No single scientific paper quite had the prevailing impact of his 1965 article in Scientific American with Jacob Fromm. This article showed the power of computational experiments and inspired visualization, and captured a generation who created CFD as a force. The only downside is the strong tendency to create CFD that is merely “Colorful Fluid Dynamics” and eschew a more measured scientific approach. Nonetheless, Frank planted the seeds that sprouted around the World.

For that matter Lax’s work while started at Los Alamos had almost no impact there. While Lax’s work formed the basis of the mathematical theory of hyperbolic PDEs and their numerical solution, and is immensely relevant to the Lab’s work, it receives almost no attention at all. Lax’s efforts had the greatest appeal in aeronautics and astrophysics through the work of Jameson and Van Leer/Roe. Interestingly enough the line of thinking from Lax did compete with the Von Neumann-Richtmyer approach in astrophysics, and resulted in the Lax thread winning out.

Von Neumann and Richtmyer’s work is the workhorse of shock physics codes to this day, but the attitude toward the method is hardly healthy. The basic methodology is viewed as being a “hack” and the values of the coefficients for artificial viscosity are merely knobs, to be adjusted. This attitude persists despite copious theory that says the opposite. Overcoming the misperceptions of artificial viscosity within a culture like the one that exists at Los Alamos (and its sister Labs the World over) is daunting, and seemingly impossible. Progress on this front is slowly happening, but the now traditional viewpoint is resilient. Lax’s work is also making inroads at the Labs primarily to some stunningly good work by French researchers led by the efforts of Pierre-Henri Maire and Bruno Depres who have created a cell-centered Lagrangian methodology that works. This was something that seemed “impossible” 10 or 15 years ago because it had been tried by a number of talented scientists, but always met with failure.

The origins of weather and climate modeling are closely related to this work. Von Neumann used his experience with shock physics at Los Alamos to confidently start the study of weather and climate in collaboration with Jules Charney. Despite the incredibly primitive state of computing, the work began shortly after World War II. Joseph Smagorinsky whose 1963 paper is jointly viewed as the beginning of global climate modeling and large eddy simulation successfully executed the second generation of the weather and climate modeling. The subgrid turbulence model with Smagorinsky’s name is nothing more than a three-dimensional extension of the Richtmyer-Von Neumann artificial viscosity. Charney suggested adding this stabilization to the simulations in a 1956 conference on the first generation of such modeling. Success with computing shocks in pursuit of nuclear weapons gave him the confidence it could be done. The connection of shock capturing dissipation to turbulence dissipation is barely acknowledged by anyone despite the very concept being immensely thought provoking.

The impact of climate science on the public perception of modern science is the topic of next week’s post. Stay tuned.