The fundamental law of computer science: As machines become more powerful, the efficiency of algorithms grows more important, not less.

– Nick Trefethen

The powerful truth of this observation by a famous mathematician seems to be lost on the dialog associated with computing. The result will be the waste of a lot of money and effort getting highly suboptimal results at the end. It shows the danger of defining public research policy on the basis of marketing slogans and poorly thought through conventional wisdom. Hopefully a more sensible and effective path can be crafted before too much longer.

One of the key unanswered questions in supercomputing is how the next generation of computers (i.e., exascale or 10^18 operations/second, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exascale_computing) would be used to the benefit of the Nation (or humanity). Thus far, the scientific community has offered up rather weak justifications for the need for exascale. In part, the scientific community should get a pass because the computing, when available, will undoubtedly be worthwhile and beneficial to discovery, industry and national security.

One of the key unanswered questions in supercomputing is how the next generation of computers (i.e., exascale or 10^18 operations/second, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exascale_computing) would be used to the benefit of the Nation (or humanity). Thus far, the scientific community has offered up rather weak justifications for the need for exascale. In part, the scientific community should get a pass because the computing, when available, will undoubtedly be worthwhile and beneficial to discovery, industry and national security.

At a deeper level, the weakness of the case for exascale highlights the extent to which the tail is now wagging the dog. Historically, the application of computing has always been preeminent and the computers themselves were always inadequate to sate the appetite for problem solving. Now we have a meta-development program for computing that exceeds our grasp of vision for problems to solve (see for example http://www.seas.harvard.edu/news/2014/07/built-for-speed-designing-exascale-computers). In the broader computing industry the use of computing is still king, but scientific computing has for some reason lost this basic rule along the way.

At a deeper level, the weakness of the case for exascale highlights the extent to which the tail is now wagging the dog. Historically, the application of computing has always been preeminent and the computers themselves were always inadequate to sate the appetite for problem solving. Now we have a meta-development program for computing that exceeds our grasp of vision for problems to solve (see for example http://www.seas.harvard.edu/news/2014/07/built-for-speed-designing-exascale-computers). In the broader computing industry the use of computing is still king, but scientific computing has for some reason lost this basic rule along the way.

Doing the right thing is more important than doing the thing right.

– Peter Drucker

The working assumption is that the bigger and faster a computer is, the better it is. This is the basis of current policy and the focus of research in supercomputing. By merely examining the broader computing industry it is easy to see how specious this assumption is. Better is a tight collaboration between machine and how the machine is used. Apple is a great example of software and elegant design trumping pure power. The spate of recent developments in innovative applications of computing is driving the economic engine around computing. The convergence of computing with communication and mass media transcends almost anything done in computing hardware. All of these lessons are there for picking, but completely lost on the supercomputing crowd who are stuck in the past, and following old ideas on an inertial trajectory.

This simply cannot continue, we must define problems to be solved that clearly benefit from the power provided by the computer. Where does this disconnect come from? I believe that the last 20-25 years have focused almost exclusively on developments associated with the nature of the hardware with the need for computing being an a priori assumption. The failure to invest in application-focused programs, algorithms, and modeling has left computing adrift. The march of the killer-micros and the emergence of computing as a major axis in the economy have deepened this development. We are left with a supercomputing program lacking the visionary basis for justifying its own existence. It basis is viewed as being axiomatic. It isn’t axiomatic; therefore we have a problem in need of immediate attention.

A large part of the reason for the current focus hinges upon the lack of appetite for risk taking in research. The capacity of computing to improve has been able to count on Moore’s law for decades and improvement happened without having to do much. It was basically a sure  thing. Granted that the transition of computing from the Crays of the 80’s and 90’s to the massively parallel machines of the 21st Century was challenging, but Moore’s law softened the difficulty. Risky algorithmic research was basically starved and ignored because the return from Moore’s law was virtually guaranteed. The result has been a couple of decades where algorithmic advances have languished due to wanton neglect. We have been able to depend on Moore’s law’s almost mechanical reliability for 50 or more years. The beginning of the end is at hand and the problems with its continuation will only mount (see the excellent post by Herb Sutter for more than I can begin to state on the topic http://herbsutter.co

thing. Granted that the transition of computing from the Crays of the 80’s and 90’s to the massively parallel machines of the 21st Century was challenging, but Moore’s law softened the difficulty. Risky algorithmic research was basically starved and ignored because the return from Moore’s law was virtually guaranteed. The result has been a couple of decades where algorithmic advances have languished due to wanton neglect. We have been able to depend on Moore’s law’s almost mechanical reliability for 50 or more years. The beginning of the end is at hand and the problems with its continuation will only mount (see the excellent post by Herb Sutter for more than I can begin to state on the topic http://herbsutter.co m/welcome-to-the-jungle/). The consequence is that risky research is the only path forward, and our current approach to managing research is woefully out of step with taking risks. If we don’t embrace risky research and take some real chances there will be a colossal crash.

m/welcome-to-the-jungle/). The consequence is that risky research is the only path forward, and our current approach to managing research is woefully out of step with taking risks. If we don’t embrace risky research and take some real chances there will be a colossal crash.

It is useful to look at history for some much needed perspective on the current state of supercomputing. At the beginning of the computing age, the problems being solved were the focus of attention, the computers were necessary vehicles. For several decades the computers and computing environment was woefully inadequate to the vision of what computational science could d o. Sometime in 1980’s the computers caught up. For about 15-20 glorious years a golden age ensued where the computers and the problems being solved were in balance. Sure the computers could be faster, but the state of programming, visualization, methods, and all the various aspects were in glorious harmony. This golden age of supercomputing is probably most clearly associated with Seymour Cray’s computers like the Cray 1, X-MP, Y-MP and C90. Then computing became more than just mainframes for accounting and supercomputers for scientists, computing became mainstream. The harmony was upset and suddenly the computers themselves lurched into the forefront of thought with the “killer micros” and massively parallel processors. Since that time supercomputing has become increasingly about hardware and we have in large part lost the vision of what we are doing with them.

o. Sometime in 1980’s the computers caught up. For about 15-20 glorious years a golden age ensued where the computers and the problems being solved were in balance. Sure the computers could be faster, but the state of programming, visualization, methods, and all the various aspects were in glorious harmony. This golden age of supercomputing is probably most clearly associated with Seymour Cray’s computers like the Cray 1, X-MP, Y-MP and C90. Then computing became more than just mainframes for accounting and supercomputers for scientists, computing became mainstream. The harmony was upset and suddenly the computers themselves lurched into the forefront of thought with the “killer micros” and massively parallel processors. Since that time supercomputing has become increasingly about hardware and we have in large part lost the vision of what we are doing with them.

Doing more things faster is no substitute for doing the right things.

– S. R. Covey

This is in large part at the core of the problems today with supercomputing focus. We are not envisioning difficult problems we want to or need to solve and finding computers that can assist us. Instead we are chasing computers that are designed through a Frankenstein monster process of combining commercial viability and constraints increasingly coming from the mobile computing market with solving yesterday’s problems with yesterday’s methods measured by yesterday’s yardstick. Almost everything about this is wrong for supercompu ting and computational science. In the process of we are losing innovation in algorithms and problem-solving strategies. For example the increasing irrelevance of applied math to computing (and particularly the applications of computing) can be traced directly to the time when the golden era ended. In almost any area that participated in the golden era the codes today are simply ports of the codes from that time to the new computers.

ting and computational science. In the process of we are losing innovation in algorithms and problem-solving strategies. For example the increasing irrelevance of applied math to computing (and particularly the applications of computing) can be traced directly to the time when the golden era ended. In almost any area that participated in the golden era the codes today are simply ports of the codes from that time to the new computers.

Management is doing things right. Leadership is doing the right things

– Peter Drucker

What we need is a fresh vision of problems to solve. Problems that matter for society are essential as are new ways of attacking old problems. As a matter of course we should not be simply solving the same old problems on a finer mesh with a more resolved geometry. Instead we should be solving these problems in better ways. Engaging in the design of devices and materials using optimization and deeply embedded error quantification. We need to be solving problems in more accurate, physically true and efficient methods. In short a new vision is needed that pushes today’s computers to be woefully inadequate. At a minimum the balance needs to be restored where the application of the computers is as important as the computers themselves. We need to realize that our thinking about using supercomputers is basically “in the box”. It is in the same box that created computing 70 years ago, and it is time to envision something bolder. We remain stuck today in the original vision where forward simulations of physical phenomena drove the creation of supercomputing.

It has become almost a cliché to say that supercomputing is an essential element to our National Security. The forays of the Chinese into the lead of supercomputing has been used as an alarm bell to call for greater support from the government. Yesterday’s missile gap has become today’s supercomputer gap. Throughout the Cold War supercomputing was used to support our national defense especially at the cutting edge in the nuclear weapons labs. At the end of the Co ld War when underground nuclear testing ended, the USA put its nuclear stockpile’s health in a scientific program known a stockpile stewardship where supercomputing plays a major role. I have argued repeatedly that the mere power of the computers has received too much priority and the way we use the computers too little, but the overall idea has merit.

ld War when underground nuclear testing ended, the USA put its nuclear stockpile’s health in a scientific program known a stockpile stewardship where supercomputing plays a major role. I have argued repeatedly that the mere power of the computers has received too much priority and the way we use the computers too little, but the overall idea has merit.

While the ascendance of the Chinese in computing power is alarming, we should be far more alarmed by the great leaps and bounds they are making in the methods to use on such computers. Their advances in computing methodology have been even more dramatic than the headline catching fastest computers. Th eir investment in intellectual capital seems to greatly exceed our own. This is a far greater threat to our security than the computers themselves (or ISIS for that matter!). This is coupled with strategic investments of the Chinese in their convention and nuclear defense including substantial improvement in technology (including innovative approaches). Today the dialog of supercomputing is solely cast in overly simplistic terms of raw power, and raw speed without the texture of how this is or can be used. We are poorly served by the dialog.

eir investment in intellectual capital seems to greatly exceed our own. This is a far greater threat to our security than the computers themselves (or ISIS for that matter!). This is coupled with strategic investments of the Chinese in their convention and nuclear defense including substantial improvement in technology (including innovative approaches). Today the dialog of supercomputing is solely cast in overly simplistic terms of raw power, and raw speed without the texture of how this is or can be used. We are poorly served by the dialog.

What gets measured gets improved.

– Peter Drucker

The public at large and our leaders are capable of much better thinking. In computing today the software is as important (or more important) than the hardware. Computing and communication are becoming a single streamlined entity and innovation is key to the industry. New applications are approaches to using the combined computing and communication capability are driving the entire area. The demands of these developments are driving the development of computing hardware in ways that are straining traditional supercomputing. Supercomputing research has been left in an extremely reactive mode of operation in response. One of the problems is the failure to pick up the mantle of innovation that has become the core of commercial computing. Another issue is a massive amount of technical debt resulting from a lack of investment and a failure to take risks.

Technical debt in computing is usually reserved for the discussion of the base of legacy code that acts as an anchor on future capability. Supercomputing certainly has this issue in spades, but it may not be the deepest aspect of its massive technical debt. The knowledge base for computing is also suffering from technical debt where we continue to use quite old methodology year past its sell-by date. Rather than develop computing along broad lines at the end of the Cold War we have produced a new cadre of legacy codes simply porting the older methods onto a new generation of computers whole cloth. New methods for solving the equations that govern phenomena were largely avoided and the focus was simply on getting the codes to work on the massively parallel computers. In addition we continued to use the new computers just like the old computers. The whole enterprise was very much “inside the box” as far as the use of computers was concerned. It became a fait accompli th at results would be better on the bigger computers.

at results would be better on the bigger computers.

One of the biggest chunks of technical debt is a well-known, but very dirty secret. For real applications we get extremely poor performance on supercomputers. It a computer is rated at one petaflop; we see something like a few percent of that performance on an actual application rendering our one-petaflop computer more like a 10 teraflop computer. This makes the government who pays for the computing unhappy in the extreme. The problem stems from competing interests and a genuine failure of tackle this difficult issue. The first interest is casting the new supercomputer is the best possible light. We have a benchmarking program that is functionally meaningless that defines who is the fastest, LINPAC. This is the LU decomposition of a massive matrix, and it has almost nothing to do with any problem that people buy supercomputers to solve. It is extremely floating point intense and optimized for computers. Even worse its characteristics are getting further and further from what actual applications do. As a result the distance between the advertised performance and the actual performance is growing with each passing year.

As bad as the problem is it is about to get much worse. About 15 years ago this problem was raised as an issue by external reviews. At that time we were getting about 3-5% of the LINPAC measured performance on new supercomputers. The numbers kept on dropping (from the 20% we got on the old vector Crays of the 80’s and 90’s). Eventually the GAO got wind of this and started to put heat on the Labs. The end result was to play ostrich and stick our head in the sand. The external reviews simply decided to quit asking the question because the answer was so depressing. The problem has not gotten any better, it has gotten worse. The problem is that any path to exascale computing creates computers that take all the trends that have been driving the actual performance lower and amplify them by orders of magnitude. We could be looking wistfully at the days of 1% of peak performance as the actual achieved result.

Fixing technical debt problems is much like dealing with a decaying physical infrastructure. In the USA we just patch things, we don’t actually deal with the core issues. Our leadership has become increasingly superficial and incapable of investing any resources in the future value of anything. It is true with physical and cyber infrastructure, research and development. Our near-term risk aversion is a compounding issue, and again in supercomputing the lack of investment and risk aversion will eventually bite us hard. In many ways Moore’s law has crippled our leadership in computing because it allowed a safe return on the investments. Risk adverse managers could simply focus on making Moore’s law work for them and guarantee them a return on work. They didn’t have to invest effort in risky algorithms or applications that might have a huge payoff, but were more likely to prove to be busts. Historically these payoffs have in aggregate provided the same benefit as Moore’s law, but the breakthroughs happened episodically and never followed the steady curve of progress that hardware advances produced.

Moore’s law is dying, and it might be the best thing to happen in a while. We have gotten lazy and stupid as a result, and losing its easy gains may have the benefit of waking the computing community up. Just because the hardware is not going to be improving for “free” doesn’t mean things can’t improve. You just have to look at other sources for progress. They are there; they have always been there. We just need to work harder now.

Let’s move to the use cases for exascale. These come in two broad categories: “in the box” and “out of the box”. As we will see the in the box cases are a hard sell because they start to become ridiculous fairly fast. More than that dealing with these cases causes us to take a long hard look at all the technical debt we have accumulated over the past couple of decades of risk adverse devotion to hardware. A perfect example is numerical linear algebra where we haven’t had an algorithmic breakthrough for 30 years. That was multigrid, which provided linear complexity. I participated in a smaller meta-breakthrough about 10 years later when Krylov method aficionados realized that multigrid was a great preconditioner, and multigrid gurus realized that Krylov methods could make multigrid far more robust. In the 20 years since almost all the effort has been on implementing these methods on “massively” parallel computers, none on improving the algorithmic scaling (or complexity).

If you want something new, you have to stop doing something old.

-Peter Drucker

Of course, producing a method with sublinear scaling would be the way to go, but it isn’t clear how to do it. Recently “big data” has come to the rescue and sublinear methods are beginning to be studied. Perhaps these ideas can migrate over to numerical linear algebra and break the deadlock. It would be a real breakthrough, and for much of computational science make a difference equal to one or two generations of supercomputers. It would be the epitome of the sort high risk, high payoff research we have been systematically eschewing for decades.

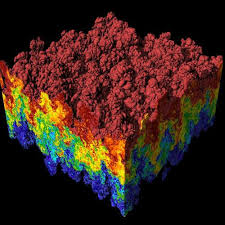

Let’s get to a few use cases as concrete examples of the problem. I’ll focus on computational fluid dynamics because its classic and I know enough to be dangerous. We can look at some archetypes like direct numerical simulation of turbulence, design calculations and shock hydrodynamics. The variables to consider are the grid, number of degrees of freedom, and operations per zone per cycle and the number of cycles. We will apply the maxim from Edward Teller about computing,

A state-of-the-art calculation requires 100 hours of CPU time on the state-of-the-art computer, independent of the decade.

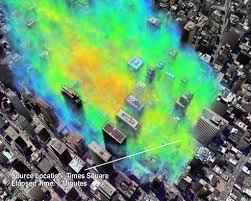

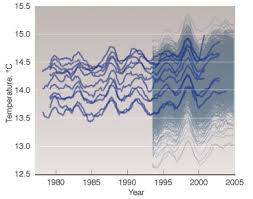

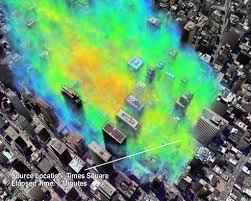

I will note that the recent study “CFD 2030” from NASA is a real tour-de-force and is highly, highly recommended (http://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20140003093). It is truly a visionary document that steps in the right direction including realistic estimates of the need for computing and visionary new concepts in using computing. I will use it as a resource for these, ballpark, “back of the envelope” estimates. If one looks at one of the canonical problems in supercomputing, turbulence in a box we can see what in the box thinking can get us (damn little). There are some fairly well established scaling laws that define what can be done with turbulence simulation. If we look at the history of direct numerical simulation (DNS) we can see the development of computing written clearly. The classical scaling of DNS goes as the Reynolds number (the non-dimensional ratio of convective to diffusive terms in the governing equations) to a high power, using Diego Donzis’ thesis as a guide the number of cells is connected to the Reynolds number by N=3.5 Re^1.5 (empirically derived). We take the number of operations per degree of freedom as 250 and assume linear scaling, and a long computation time where the number of steps is 100 times the number of linear mesh points. Note that the proper Reynolds number in the table is the Taylor microscale Reynolds number that scales as roughly the square root of the more commonly known macroscale Reynolds number

in a box we can see what in the box thinking can get us (damn little). There are some fairly well established scaling laws that define what can be done with turbulence simulation. If we look at the history of direct numerical simulation (DNS) we can see the development of computing written clearly. The classical scaling of DNS goes as the Reynolds number (the non-dimensional ratio of convective to diffusive terms in the governing equations) to a high power, using Diego Donzis’ thesis as a guide the number of cells is connected to the Reynolds number by N=3.5 Re^1.5 (empirically derived). We take the number of operations per degree of freedom as 250 and assume linear scaling, and a long computation time where the number of steps is 100 times the number of linear mesh points. Note that the proper Reynolds number in the table is the Taylor microscale Reynolds number that scales as roughly the square root of the more commonly known macroscale Reynolds number

| N |

Ops/second |

Reynolds Number |

| 32 |

1.2 Mflop |

35 |

| 128 |

300 Mflop |

90 |

| 256 |

5 Gflop |

140 |

| 1024 |

1.3 Tflop |

250 |

| 4096 |

325 Tflop |

900 |

| 10,000 |

12 Pflop |

1600 |

| 20,000 |

185 Pflop |

2600 |

| 40,000 |

3 Eflop |

4100 |

This assumes that the efficiency of calculations is constant over the fifty-year period of time this would imply. It most certainly is not. The decrease in efficiency is at least a factor of 10 if not more. Applying the factor of ten decrease in efficiency means that on an exascale computer as defined by LINPAC we would be solving the N=20,000 case at a 5% efficiency, which implicitly assumed the efficiency was 50% back in the time of the first N=32 DNS calculations. Ironically as the use case becomes smaller the necessary efficiency decreases. Currently the largest DNS is equivalent to about N=6000, which seems to imply that the efficiency is on the order of 15% (this takes 1.5Pflop by my estimation method). This exercise can then be applied almost whole cloth to large eddy simulation (LES) that is (almost) direct numerical simulation with a coarser grid and modest amount of additional modeling. It is notable that this is the application of scaling to the most idealized turbulence imaginable and avoids the mass of complications people would really be interested in.

The out of the box examples are much more interesting because they point to changing how computers are used. These are a mixture of evolutionary changes with revolutionary approaches. They are dangerous to the status quo, and success will require some serious risk-taking. For this reason they might not happen, our institutions and management are terrible at taking risks. As an example I will stick with fluid dynamics, but add embedded optimization with error and uncertainty estimation. In an aeronautical setting one might be changing the details or geometry of a wing or flight body to achieve the best possible performance (say for instance, lower drag) subject to constraints such as some standard for lift. Another interesting approach might examine the statistical response of a design to differences in the microstructure of the material. This sort of simulation might start to get at questions associated with failure of devices that have eluded simulation via the traditional approaches utilizing purely forward (classical) simulation.

Software gets slower faster than hardware gets faster.

– N. Wirth

One way to project to exascale would be to apply some large sample of forward calculations to statistically sample a user case of interest. For example 1000 state-of-the-art DNS calculations (N=6000) would produce an exascale of demand. The problem is that most supercomputing sites view this sort of use of the computers as cheating! What would it take to do a less crude and more embedded uncertainty quantification approach might use extra degrees of freedom to describe the evolution of uncertainty. The question is how the solution efficiency scales with the additional degrees of freedom and how to implement and describe the results of the calculations.

For the slightly more out of the box case for exascale let’s look at a solution to the Vlasov-Maxwell-Boltzmann equation(s) for solving the evolution of a plasma. This is a seven (!) dimensional problem so it ought get big really fast. In addition we can add some additional degrees of freedom that might provide the ability to solve the problem with embedded uncertainty, or a high order method like discontinuous Galerkin (or both!). I’ll just continue with some assumptions from the DNS example regarding the floating-point intensity to integrate each degree of freedom (1000 operations per variable per degree of freedom, and a day of total runtime)

For the slightly more out of the box case for exascale let’s look at a solution to the Vlasov-Maxwell-Boltzmann equation(s) for solving the evolution of a plasma. This is a seven (!) dimensional problem so it ought get big really fast. In addition we can add some additional degrees of freedom that might provide the ability to solve the problem with embedded uncertainty, or a high order method like discontinuous Galerkin (or both!). I’ll just continue with some assumptions from the DNS example regarding the floating-point intensity to integrate each degree of freedom (1000 operations per variable per degree of freedom, and a day of total runtime)

| Nspace |

Nvelocity |

Ndof/variable |

Ops/second |

| 32 |

20 |

1 |

40 Gflop |

| 64 |

40 |

1 |

2.5 Tflop |

| 128 |

80 |

1 |

160 Tflop |

| 256 |

160 |

1 |

10 Pflop |

| 512 |

160 |

1 |

80 Pflop |

| 1024 |

160 |

1 |

650 Pflop |

| 2048 |

160 |

1 |

5.2 Eflop |

| 32 |

20 |

20 |

776 Gflop |

| 64 |

40 |

20 |

50 Tflop |

| 128 |

80 |

20 |

3.2 Pflop |

| 256 |

160 |

20 |

204 Pflop |

| 512 |

160 |

20 |

1.6 Eflop |

We immediately see that the calculations have a great potential to swamp any computer we can envision for the near future. I will fully acknowledge that these estimates are completely couched in the “bigger is better” mindset.

What we really need is a way of harnessing innovative ways of applying computing. For example, what can be done to r eplace expensive time consuming testing of materials for failure? Can this be reliably computed? And if not, why not? Can we open up new spaces for designing items via computing and couple it to additive manufacturing? Can we rely upon this approach to get new efficiencies and agility in our industries? This is exactly the sort of visionary approach that is missing today from the dialog. The same approach could be used to work on the mechanical design of parts in a car, or almost anything else if significant embedded uncertainty or optimization were included in the calculation. This is an immense potential use of computing to make the World better. We will quickly see that envisioning new application much more rapidly saturates the capacity of computing keep up. It also drives the development of new algorithms, and mathematics to support its use.

eplace expensive time consuming testing of materials for failure? Can this be reliably computed? And if not, why not? Can we open up new spaces for designing items via computing and couple it to additive manufacturing? Can we rely upon this approach to get new efficiencies and agility in our industries? This is exactly the sort of visionary approach that is missing today from the dialog. The same approach could be used to work on the mechanical design of parts in a car, or almost anything else if significant embedded uncertainty or optimization were included in the calculation. This is an immense potential use of computing to make the World better. We will quickly see that envisioning new application much more rapidly saturates the capacity of computing keep up. It also drives the development of new algorithms, and mathematics to support its use.

“Results are gained by exploiting opportunities, not by solving problems.”

-Peter Drucker

Part of the need for realizing the need for out of the box thinking comes from observing the broader computing world. Today much more value comes from innovative application than the hardware itself. New applications for computing are driving massive economic and cultural change. Massive value is being created out of thin air. Part of this entails risk, and risk is something our R&D community has become extremely adverse to. We are in dire need of new ideas and new approaches to applying computational science. The old ideas were great, but now grow tired and really lack the capacity to advance the state much longer.

Part of the need for realizing the need for out of the box thinking comes from observing the broader computing world. Today much more value comes from innovative application than the hardware itself. New applications for computing are driving massive economic and cultural change. Massive value is being created out of thin air. Part of this entails risk, and risk is something our R&D community has become extremely adverse to. We are in dire need of new ideas and new approaches to applying computational science. The old ideas were great, but now grow tired and really lack the capacity to advance the state much longer.

Much in the same fashion as Moore’s law, the old vision of computing is running out of steam, and its time to reboot.

president who seemingly represents the left is more conservative than the Republican president 40 year ago, Nixon. Nixon’s policies such a founding the EPA, pulling out of Vietnam, Court appointees, and détente with China would all peg him to the left of Obama. Despite this, in a stunning departure from historical reality, the right constantly charges Obama with being socialist, communist and worse. None of these charges has even the slightest degree of basis in fact, yet they continue. What the hell is going on? How did we get here?

president who seemingly represents the left is more conservative than the Republican president 40 year ago, Nixon. Nixon’s policies such a founding the EPA, pulling out of Vietnam, Court appointees, and détente with China would all peg him to the left of Obama. Despite this, in a stunning departure from historical reality, the right constantly charges Obama with being socialist, communist and worse. None of these charges has even the slightest degree of basis in fact, yet they continue. What the hell is going on? How did we get here? e they were expected to be profitable, but also operate in the best interests of all its stakeholders, not just stockholders. These stakeholders were comprised of customers, employees and the communities where they operated in addition to the stockholders. This formed a deep social contract with business, the country and its citizens and became the operational ethos during that time. It was the time when the United States had its greatest standing relative to the rest of the World. It was the ethos that allowed the middle class to rise to prominence and vibrancy. It was the ethos that ultimately opened the door to progress and social change that benefited everyone.

e they were expected to be profitable, but also operate in the best interests of all its stakeholders, not just stockholders. These stakeholders were comprised of customers, employees and the communities where they operated in addition to the stockholders. This formed a deep social contract with business, the country and its citizens and became the operational ethos during that time. It was the time when the United States had its greatest standing relative to the rest of the World. It was the ethos that allowed the middle class to rise to prominence and vibrancy. It was the ethos that ultimately opened the door to progress and social change that benefited everyone. responsibility of business. The only other stipulation was to play by the “rules”. Over time, the Nation’s laws have been modified to adopt these principles and allow their operation to be even more profitable (or at the very least money makers for the ruling class). Businesses still play by the rules, even if they are writing these rules via forms of legalized bribery. This bribery has been legalized through the Supreme Court’s ironically named Citizen’s United case. They follow the rules, but the morality of their actions is unquestionably dark and self-serving.

responsibility of business. The only other stipulation was to play by the “rules”. Over time, the Nation’s laws have been modified to adopt these principles and allow their operation to be even more profitable (or at the very least money makers for the ruling class). Businesses still play by the rules, even if they are writing these rules via forms of legalized bribery. This bribery has been legalized through the Supreme Court’s ironically named Citizen’s United case. They follow the rules, but the morality of their actions is unquestionably dark and self-serving. period where modern day Robber Barons rule our country. The question is what came first, the conservative political movement or the greedy business principles? To what extent are they the same thing? Or do they exist in a symbiotic relationship, self-reinforcing their capacity to damage our Nation so that a few people can siphon their fortunes from the carcass of the once great Nation? So did Friedman’s perverse ideas lead the way, or did the spirit of the National Review and Nixon’s petty tyranny give birth to the Reagan revolution?

period where modern day Robber Barons rule our country. The question is what came first, the conservative political movement or the greedy business principles? To what extent are they the same thing? Or do they exist in a symbiotic relationship, self-reinforcing their capacity to damage our Nation so that a few people can siphon their fortunes from the carcass of the once great Nation? So did Friedman’s perverse ideas lead the way, or did the spirit of the National Review and Nixon’s petty tyranny give birth to the Reagan revolution? uth that forms the backbone of the Republican majority. This has formed a coalition that feeds off of deep racial hatred and fear coupled with money and greed from the top of the corporate food chain. Our politics serves the interests of the rich and they have turned the seething historical hatred and racism to the dark purpose of sustaining their stranglehold on the Nation’s wealth.

uth that forms the backbone of the Republican majority. This has formed a coalition that feeds off of deep racial hatred and fear coupled with money and greed from the top of the corporate food chain. Our politics serves the interests of the rich and they have turned the seething historical hatred and racism to the dark purpose of sustaining their stranglehold on the Nation’s wealth. o longer act strategically, everything is tactical. Companies are run on the basis of the quarterly report, and investors will divest themselves once the purpose of maximizing their take has been fulfilled. They turn their attentions to the next victim. Our government is equally short sighted and it is arguable that the longest time horizon available is the four-year presidential cycle, with the annual budget or biannual congressional elections forming a stronger basis for the time horizon that matters. These all seem long to the manic pace that business life and death runs at. We act as if we have no future and perhaps we don’t.

o longer act strategically, everything is tactical. Companies are run on the basis of the quarterly report, and investors will divest themselves once the purpose of maximizing their take has been fulfilled. They turn their attentions to the next victim. Our government is equally short sighted and it is arguable that the longest time horizon available is the four-year presidential cycle, with the annual budget or biannual congressional elections forming a stronger basis for the time horizon that matters. These all seem long to the manic pace that business life and death runs at. We act as if we have no future and perhaps we don’t.

research has reached a crisis level with the mindset creating the direct opposite of the intended outcome (at least I’m assuming the intent is positive). All of this is packed into the soul-crushing drumbeat of the quarterly progress report and constant reviews. Those of us going through this process have almost uniformly adopted a way of managing this cycle of mediocrity. One always picks deliverables that have already been completed, or can be completed with no risk. Milestones are the same thing; the work has already been done. All that is needed for success is just showing up and checking the boxes. No one is supposed to put forth any goals that might be challenging or possibly be missed. No risks should be taken.

research has reached a crisis level with the mindset creating the direct opposite of the intended outcome (at least I’m assuming the intent is positive). All of this is packed into the soul-crushing drumbeat of the quarterly progress report and constant reviews. Those of us going through this process have almost uniformly adopted a way of managing this cycle of mediocrity. One always picks deliverables that have already been completed, or can be completed with no risk. Milestones are the same thing; the work has already been done. All that is needed for success is just showing up and checking the boxes. No one is supposed to put forth any goals that might be challenging or possibly be missed. No risks should be taken. as been mindlessly adopted as the model for managing anything. This has created the quarterly progress mentality, which must always succeed. Corporate American has the same mantra where a Company must show a good balance sheet every quarter or suffer the wrath of the stock market. The balance sheets are cooked and companies are shaken down regardless of the long-term damage done. The long-term perspective has been destroyed. Companies invest little or nothing R&D continually savaging their own future to assure a good quarterly report. Given this model of propriety we shouldn’t express any surprise over the damage done where this approach as been adopted. Still some things still slip through the cracks.

as been mindlessly adopted as the model for managing anything. This has created the quarterly progress mentality, which must always succeed. Corporate American has the same mantra where a Company must show a good balance sheet every quarter or suffer the wrath of the stock market. The balance sheets are cooked and companies are shaken down regardless of the long-term damage done. The long-term perspective has been destroyed. Companies invest little or nothing R&D continually savaging their own future to assure a good quarterly report. Given this model of propriety we shouldn’t express any surprise over the damage done where this approach as been adopted. Still some things still slip through the cracks. The National Ignition Facility (NIF) is a shining example of failure at high-level goals. I have to admit feeling a certain smugness when they failure, but perhaps I was too harsh. NIF has lofty and worthy goals, success would have been glorious for NIF and for the Nation and World. It is too bad they didn’t succeed. Like all failures, the real failure would be not learning from the mistake. The jury is still out on whether or not they will learn.

The National Ignition Facility (NIF) is a shining example of failure at high-level goals. I have to admit feeling a certain smugness when they failure, but perhaps I was too harsh. NIF has lofty and worthy goals, success would have been glorious for NIF and for the Nation and World. It is too bad they didn’t succeed. Like all failures, the real failure would be not learning from the mistake. The jury is still out on whether or not they will learn. and worthy goal and they went for it. That is really a good thing. Now, it is important that we all learn from this and science progresses to better attempt ignition in the future. We need to understand how to predict what actually happened. We need our knowledge to grow and improve future performance. If these improvements do not materialize then NIF will really be a failure.

and worthy goal and they went for it. That is really a good thing. Now, it is important that we all learn from this and science progresses to better attempt ignition in the future. We need to understand how to predict what actually happened. We need our knowledge to grow and improve future performance. If these improvements do not materialize then NIF will really be a failure. One of the key unanswered questions in supercomputing is how the next generation of computers (i.e., exascale or 10^18 operations/second,

One of the key unanswered questions in supercomputing is how the next generation of computers (i.e., exascale or 10^18 operations/second,  At a deeper level, the weakness of the case for exascale highlights the extent to which the tail is now wagging the dog. Historically, the application of computing has always been preeminent and the computers themselves were always inadequate to sate the appetite for problem solving. Now we have a meta-development program for computing that exceeds our grasp of vision for problems to solve (see for example

At a deeper level, the weakness of the case for exascale highlights the extent to which the tail is now wagging the dog. Historically, the application of computing has always been preeminent and the computers themselves were always inadequate to sate the appetite for problem solving. Now we have a meta-development program for computing that exceeds our grasp of vision for problems to solve (see for example  thing. Granted that the transition of computing from the Crays of the 80’s and 90’s to the massively parallel machines of the 21st Century was challenging, but Moore’s law softened the difficulty. Risky algorithmic research was basically starved and ignored because the return from Moore’s law was virtually guaranteed. The result has been a couple of decades where algorithmic advances have languished due to wanton neglect. We have been able to depend on Moore’s law’s almost mechanical reliability for 50 or more years. The beginning of the end is at hand and the problems with its continuation will only mount (see the excellent post by Herb Sutter for more than I can begin to state on the topic

thing. Granted that the transition of computing from the Crays of the 80’s and 90’s to the massively parallel machines of the 21st Century was challenging, but Moore’s law softened the difficulty. Risky algorithmic research was basically starved and ignored because the return from Moore’s law was virtually guaranteed. The result has been a couple of decades where algorithmic advances have languished due to wanton neglect. We have been able to depend on Moore’s law’s almost mechanical reliability for 50 or more years. The beginning of the end is at hand and the problems with its continuation will only mount (see the excellent post by Herb Sutter for more than I can begin to state on the topic  m/welcome-to-the-jungle/

m/welcome-to-the-jungle/ o. Sometime in 1980’s the computers caught up. For about 15-20 glorious years a golden age ensued where the computers and the problems being solved were in balance. Sure the computers could be faster, but the state of programming, visualization, methods, and all the various aspects were in glorious harmony. This golden age of supercomputing is probably most clearly associated with Seymour Cray’s computers like the Cray 1, X-MP, Y-MP and C90. Then computing became more than just mainframes for accounting and supercomputers for scientists, computing became mainstream. The harmony was upset and suddenly the computers themselves lurched into the forefront of thought with the “killer micros” and massively parallel processors. Since that time supercomputing has become increasingly about hardware and we have in large part lost the vision of what we are doing with them.

o. Sometime in 1980’s the computers caught up. For about 15-20 glorious years a golden age ensued where the computers and the problems being solved were in balance. Sure the computers could be faster, but the state of programming, visualization, methods, and all the various aspects were in glorious harmony. This golden age of supercomputing is probably most clearly associated with Seymour Cray’s computers like the Cray 1, X-MP, Y-MP and C90. Then computing became more than just mainframes for accounting and supercomputers for scientists, computing became mainstream. The harmony was upset and suddenly the computers themselves lurched into the forefront of thought with the “killer micros” and massively parallel processors. Since that time supercomputing has become increasingly about hardware and we have in large part lost the vision of what we are doing with them. ting and computational science. In the process of we are losing innovation in algorithms and problem-solving strategies. For example the increasing irrelevance of applied math to computing (and particularly the applications of computing) can be traced directly to the time when the golden era ended. In almost any area that participated in the golden era the codes today are simply ports of the codes from that time to the new computers.

ting and computational science. In the process of we are losing innovation in algorithms and problem-solving strategies. For example the increasing irrelevance of applied math to computing (and particularly the applications of computing) can be traced directly to the time when the golden era ended. In almost any area that participated in the golden era the codes today are simply ports of the codes from that time to the new computers. ld War when underground nuclear testing ended, the USA put its nuclear stockpile’s health in a scientific program known a stockpile stewardship where supercomputing plays a major role. I have argued repeatedly that the mere power of the computers has received too much priority and the way we use the computers too little, but the overall idea has merit.

ld War when underground nuclear testing ended, the USA put its nuclear stockpile’s health in a scientific program known a stockpile stewardship where supercomputing plays a major role. I have argued repeatedly that the mere power of the computers has received too much priority and the way we use the computers too little, but the overall idea has merit. eir investment in intellectual capital seems to greatly exceed our own. This is a far greater threat to our security than the computers themselves (or ISIS for that matter!). This is coupled with strategic investments of the Chinese in their convention and nuclear defense including substantial improvement in technology (including innovative approaches). Today the dialog of supercomputing is solely cast in overly simplistic terms of raw power, and raw speed without the texture of how this is or can be used. We are poorly served by the dialog.

eir investment in intellectual capital seems to greatly exceed our own. This is a far greater threat to our security than the computers themselves (or ISIS for that matter!). This is coupled with strategic investments of the Chinese in their convention and nuclear defense including substantial improvement in technology (including innovative approaches). Today the dialog of supercomputing is solely cast in overly simplistic terms of raw power, and raw speed without the texture of how this is or can be used. We are poorly served by the dialog. at results would be better on the bigger computers.

at results would be better on the bigger computers.

in a box we can see what in the box thinking can get us (damn little). There are some fairly well established scaling laws that define what can be done with turbulence simulation. If we look at the history of direct numerical simulation (DNS) we can see the development of computing written clearly. The classical scaling of DNS goes as the Reynolds number (the non-dimensional ratio of convective to diffusive terms in the governing equations) to a high power, using Diego Donzis’ thesis as a guide the number of cells is connected to the Reynolds number by N=3.5 Re^1.5 (empirically derived). We take the number of operations per degree of freedom as 250 and assume linear scaling, and a long computation time where the number of steps is 100 times the number of linear mesh points. Note that the proper Reynolds number in the table is the Taylor microscale Reynolds number that scales as roughly the square root of the more commonly known macroscale Reynolds number

in a box we can see what in the box thinking can get us (damn little). There are some fairly well established scaling laws that define what can be done with turbulence simulation. If we look at the history of direct numerical simulation (DNS) we can see the development of computing written clearly. The classical scaling of DNS goes as the Reynolds number (the non-dimensional ratio of convective to diffusive terms in the governing equations) to a high power, using Diego Donzis’ thesis as a guide the number of cells is connected to the Reynolds number by N=3.5 Re^1.5 (empirically derived). We take the number of operations per degree of freedom as 250 and assume linear scaling, and a long computation time where the number of steps is 100 times the number of linear mesh points. Note that the proper Reynolds number in the table is the Taylor microscale Reynolds number that scales as roughly the square root of the more commonly known macroscale Reynolds number For the slightly more out of the box case for exascale let’s look at a solution to the Vlasov-Maxwell-Boltzmann equation(s) for solving the evolution of a plasma. This is a seven (!) dimensional problem so it ought get big really fast. In addition we can add some additional degrees of freedom that might provide the ability to solve the problem with embedded uncertainty, or a high order method like discontinuous Galerkin (or both!). I’ll just continue with some assumptions from the DNS example regarding the floating-point intensity to integrate each degree of freedom (1000 operations per variable per degree of freedom, and a day of total runtime)

For the slightly more out of the box case for exascale let’s look at a solution to the Vlasov-Maxwell-Boltzmann equation(s) for solving the evolution of a plasma. This is a seven (!) dimensional problem so it ought get big really fast. In addition we can add some additional degrees of freedom that might provide the ability to solve the problem with embedded uncertainty, or a high order method like discontinuous Galerkin (or both!). I’ll just continue with some assumptions from the DNS example regarding the floating-point intensity to integrate each degree of freedom (1000 operations per variable per degree of freedom, and a day of total runtime) eplace expensive time consuming testing of materials for failure? Can this be reliably computed? And if not, why not? Can we open up new spaces for designing items via computing and couple it to additive manufacturing? Can we rely upon this approach to get new efficiencies and agility in our industries? This is exactly the sort of visionary approach that is missing today from the dialog. The same approach could be used to work on the mechanical design of parts in a car, or almost anything else if significant embedded uncertainty or optimization were included in the calculation. This is an immense potential use of computing to make the World better. We will quickly see that envisioning new application much more rapidly saturates the capacity of computing keep up. It also drives the development of new algorithms, and mathematics to support its use.

eplace expensive time consuming testing of materials for failure? Can this be reliably computed? And if not, why not? Can we open up new spaces for designing items via computing and couple it to additive manufacturing? Can we rely upon this approach to get new efficiencies and agility in our industries? This is exactly the sort of visionary approach that is missing today from the dialog. The same approach could be used to work on the mechanical design of parts in a car, or almost anything else if significant embedded uncertainty or optimization were included in the calculation. This is an immense potential use of computing to make the World better. We will quickly see that envisioning new application much more rapidly saturates the capacity of computing keep up. It also drives the development of new algorithms, and mathematics to support its use. Part of the need for realizing the need for out of the box thinking comes from observing the broader computing world. Today much more value comes from innovative application than the hardware itself. New applications for computing are driving massive economic and cultural change. Massive value is being created out of thin air. Part of this entails risk, and risk is something our R&D community has become extremely adverse to. We are in dire need of new ideas and new approaches to applying computational science. The old ideas were great, but now grow tired and really lack the capacity to advance the state much longer.

Part of the need for realizing the need for out of the box thinking comes from observing the broader computing world. Today much more value comes from innovative application than the hardware itself. New applications for computing are driving massive economic and cultural change. Massive value is being created out of thin air. Part of this entails risk, and risk is something our R&D community has become extremely adverse to. We are in dire need of new ideas and new approaches to applying computational science. The old ideas were great, but now grow tired and really lack the capacity to advance the state much longer. leads to decline and “good enough” turns into old-fashioned and backwards looking nostalgia. In the case of technical problem solving the things that are good enough are a scaffolding for the hard problems you are asked to solve. Often this scaffolding becomes a box you construct around yourself. It can ultimately limit your ability to solve the problem rather than enabling you. As Clay Shirky says,

leads to decline and “good enough” turns into old-fashioned and backwards looking nostalgia. In the case of technical problem solving the things that are good enough are a scaffolding for the hard problems you are asked to solve. Often this scaffolding becomes a box you construct around yourself. It can ultimately limit your ability to solve the problem rather than enabling you. As Clay Shirky says,

It took a technology that clearly took phones to whole new level, the iPhone to push the technology. Now the people who haven’t made the change are a small slice of the population without either the inclination or resources for a mobile phone. What made the difference? The iPhone was more than a phone, it was a mini computer that put the Internet at your fingertips, and new modes of communication into play. All of these pushed the mobile phone over the line. As Steve Jobs famously noted,

It took a technology that clearly took phones to whole new level, the iPhone to push the technology. Now the people who haven’t made the change are a small slice of the population without either the inclination or resources for a mobile phone. What made the difference? The iPhone was more than a phone, it was a mini computer that put the Internet at your fingertips, and new modes of communication into play. All of these pushed the mobile phone over the line. As Steve Jobs famously noted, their attitude on phones spills over to other things. They have made huge strides with modern electronics and I have hope. They still have issues with integrating cutting edge research into the delivery of major products. There is too much acceptance of old technology and good enough thinking is far too easy to find. Given their devotion to Edisonian mode engineering, they might do well to listen to Thomas Edison’s advise,

their attitude on phones spills over to other things. They have made huge strides with modern electronics and I have hope. They still have issues with integrating cutting edge research into the delivery of major products. There is too much acceptance of old technology and good enough thinking is far too easy to find. Given their devotion to Edisonian mode engineering, they might do well to listen to Thomas Edison’s advise, out the margin of safety on various design decisions or analyses to account for the possibility that the formulas being used are off, or maybe you made a mistake, or forgot to account for something. It’s all the unknowns, including the “unknown unknowns” we keep hearing about. The true depth of the concept is simply passed over by the undergraduate instruction where a bit more contemplation would serve everyone so much better. It would serve to inject some necessary humility into the dialog and provide context for vibrant research in the future.

out the margin of safety on various design decisions or analyses to account for the possibility that the formulas being used are off, or maybe you made a mistake, or forgot to account for something. It’s all the unknowns, including the “unknown unknowns” we keep hearing about. The true depth of the concept is simply passed over by the undergraduate instruction where a bit more contemplation would serve everyone so much better. It would serve to inject some necessary humility into the dialog and provide context for vibrant research in the future. When I was first introducted to safety factors it wasn’t treated like anything profound or terribly important. Just a “best practice” with no philosophical context for what it means. Upon my return to this topic in the context of recent research, it began to dawn on me that safety factors are really deep and conceptually rich. The fact that there is simply a lot that we don’t know, or even know we don’t know is potentially terrifying. We could be screwing up horribly and not even know it. At some other level what the safety factor is really telling you that the vaunted research embedded in the formulas you’re applying is potentially wrong or inapplicable to your situation. What the professors didn’t say to you so plainly is that the research of the greats might be just plain wrong. In other words, the greatest research in their field might not be worth completely trusting.

When I was first introducted to safety factors it wasn’t treated like anything profound or terribly important. Just a “best practice” with no philosophical context for what it means. Upon my return to this topic in the context of recent research, it began to dawn on me that safety factors are really deep and conceptually rich. The fact that there is simply a lot that we don’t know, or even know we don’t know is potentially terrifying. We could be screwing up horribly and not even know it. At some other level what the safety factor is really telling you that the vaunted research embedded in the formulas you’re applying is potentially wrong or inapplicable to your situation. What the professors didn’t say to you so plainly is that the research of the greats might be just plain wrong. In other words, the greatest research in their field might not be worth completely trusting. hing. The truth is we don’t know shit. So many important things are simply mysteries, and as we unveil their secrets, new mysteries will rise to take their place. We never really know the truth, we just know what we see, which is deeply influenced by how we ask the question in the first place. We can predict precious little with the sort of confidence that some would have us believe. Surprises are awaiting us around every corner, and we have so much hard work to do. Progress is needed on so many fronts.

hing. The truth is we don’t know shit. So many important things are simply mysteries, and as we unveil their secrets, new mysteries will rise to take their place. We never really know the truth, we just know what we see, which is deeply influenced by how we ask the question in the first place. We can predict precious little with the sort of confidence that some would have us believe. Surprises are awaiting us around every corner, and we have so much hard work to do. Progress is needed on so many fronts. rate and converged solution. The distance between your numerical solution and the estimate of the converged solution is the numerical error bar, which is multiplied by a factor that depends upon how hinky the estimates are, the hinkier the estimate, the larger the safety factor. Again we have precise and detailed analysis that is augmented by a factor to account for the slop (well not slop, the nonlinearity). A truism is that if we lived in a linear world, safety factors wouldn’t be necessary. Equally true is that a linear world would be dull as dirt.

rate and converged solution. The distance between your numerical solution and the estimate of the converged solution is the numerical error bar, which is multiplied by a factor that depends upon how hinky the estimates are, the hinkier the estimate, the larger the safety factor. Again we have precise and detailed analysis that is augmented by a factor to account for the slop (well not slop, the nonlinearity). A truism is that if we lived in a linear world, safety factors wouldn’t be necessary. Equally true is that a linear world would be dull as dirt.