Good judgment comes from experience, and experience – well, that comes from poor judgment.

― A.A. Milne

To avoid the sort of implicit assumption of ZERO uncertainty one can use (expert) judgment to fill in the information gap. This can be accomplished in a distinctly principled fashion and always works better with a basis in evidence. The key is the recognition that we base our uncertainty on a model (a model that is associated with error too). The models are fairly standard and need a certain minimum amount of information to be solvable, and we are always better off with too much information making it effectively over-determined. Here we look at several forms of models that lead to uncertainty estimation including discretization error, and statistical models applicable to epistemic or experimental uncertainty.

To avoid the sort of implicit assumption of ZERO uncertainty one can use (expert) judgment to fill in the information gap. This can be accomplished in a distinctly principled fashion and always works better with a basis in evidence. The key is the recognition that we base our uncertainty on a model (a model that is associated with error too). The models are fairly standard and need a certain minimum amount of information to be solvable, and we are always better off with too much information making it effectively over-determined. Here we look at several forms of models that lead to uncertainty estimation including discretization error, and statistical models applicable to epistemic or experimental uncertainty.

Maturity, one discovers, has everything to do with the acceptance of ‘not knowing.

― Mark Z. Danielewski

For discretization error the model is quite simple where

is the mesh converged solution,

is the solution on the

mesh and

is the mesh length scale,

is the (observed) rate of convergence, and

is a proportionality constant. We have three unknowns so we need at least

meshes to solve the error model exactly or more if we solve it in some sort of optimal manner. We recently had a method published that discusses how to include expert judgment in the determination of numerical error and uncertainty using models of this type. This model can be solved along with data using minimization techniques including the expert judgment as constraints on the solution for the unknowns. For both the over- or the under-determined cases different minimizations one can get multiple solutions to the model and robust statistical techniques may be used to find the “best” answers. This means that one needs to resort to more than simple curve fitting, and least squares procedures; one needs to solve a nonlinear problem associated with minimizing the fitting error (i.e., residuals) with respect to other error representations.

meshes to solve the error model exactly or more if we solve it in some sort of optimal manner. We recently had a method published that discusses how to include expert judgment in the determination of numerical error and uncertainty using models of this type. This model can be solved along with data using minimization techniques including the expert judgment as constraints on the solution for the unknowns. For both the over- or the under-determined cases different minimizations one can get multiple solutions to the model and robust statistical techniques may be used to find the “best” answers. This means that one needs to resort to more than simple curve fitting, and least squares procedures; one needs to solve a nonlinear problem associated with minimizing the fitting error (i.e., residuals) with respect to other error representations.

For extreme under-determined cases unknown vari ables can be completely eliminated by simply choosing the solution based on expert judgment. For numerical error an obvious example is assuming that calculations are converging at an expert-defined rate. Of course the rate assumed needs an adequate justification based on a combination of information associated with the nature of the numerical method and the solution to the problem. A key assumption that often does not hold up is the achievement of the method’s theoretical rate of convergence for realistic problems. In many cases a high-order method will perform at a lower rate of convergence because the problem has a structure with less regularity than necessary for the high-order accuracy. Problems with shocks or other forms of discontinuities will not usually support high-order results and a good operating assumption is a first-order convergence rate.

ables can be completely eliminated by simply choosing the solution based on expert judgment. For numerical error an obvious example is assuming that calculations are converging at an expert-defined rate. Of course the rate assumed needs an adequate justification based on a combination of information associated with the nature of the numerical method and the solution to the problem. A key assumption that often does not hold up is the achievement of the method’s theoretical rate of convergence for realistic problems. In many cases a high-order method will perform at a lower rate of convergence because the problem has a structure with less regularity than necessary for the high-order accuracy. Problems with shocks or other forms of discontinuities will not usually support high-order results and a good operating assumption is a first-order convergence rate.

To make things concrete let’s tackle a couple of examples of how all of this might work. In the paper published recently we looked at solution verification when people use two meshes instead of the three needed to fully determine the error model. This seems kind of extreme, but in this post the example is the cases where people only use a single mesh. Seemingly we can do nothing at all to estimate uncertainty, but as I explained last week, this is the time to bear down and include an uncertainty because it is the most uncertain situation, and the most important time to assess it. Instead people throw up their hands and do nothing at all, which is the worst thing to do. So we have a single solution

To make things concrete let’s tackle a couple of examples of how all of this might work. In the paper published recently we looked at solution verification when people use two meshes instead of the three needed to fully determine the error model. This seems kind of extreme, but in this post the example is the cases where people only use a single mesh. Seemingly we can do nothing at all to estimate uncertainty, but as I explained last week, this is the time to bear down and include an uncertainty because it is the most uncertain situation, and the most important time to assess it. Instead people throw up their hands and do nothing at all, which is the worst thing to do. So we have a single solution at

and need to add information to allow the solution of our error model,

. The simplest way to get to an solvable error model is to simply propose a value for the mesh converged solution,

, which then can be used to provide an uncertainty estimate,

|A –

multiplied by an appropriate safety factor

.

This is a rather strong assumption to make. We might be better served by providing a range values for either the convergence rate of the solution itself. In this way we provide a bit more deference in what we are suggesting as the level of uncertainty, which is definitely called for in this case since we are so information poor. Again the use of an appropriate safety factor is called for, on the order of 2 to 3 in value. From statistical arguments the safety factor of 2 has some merit while 3 is associated with solution verification practice proposed by Roache. All of this is strongly associated with the need to make an estimate in a case where too little work has been done to make a direct estimate. If we are adding information that is weakly related to the actual problem we are solving, the safety factor is essential to account for the lack of knowledge. Furthermore we want to enable the circumstance where more work in active problem solving will allow the uncertainties to be reduced!

A lot of this information is probably good to include as part of the analysis when you have enough information too. The right way to think about this information is as constraints on the solution. If the constraints are active they have been triggered by the analysis and help determine the solution. If the constraints have no effect on the solution then they are proven to be correct given the data. In this way the solution can be shown to be consistent with the views of the expertise. If one is in the circumstance where the expert judgment is completely determining the solution, one should be very wary as this is a big red flag.

A lot of this information is probably good to include as part of the analysis when you have enough information too. The right way to think about this information is as constraints on the solution. If the constraints are active they have been triggered by the analysis and help determine the solution. If the constraints have no effect on the solution then they are proven to be correct given the data. In this way the solution can be shown to be consistent with the views of the expertise. If one is in the circumstance where the expert judgment is completely determining the solution, one should be very wary as this is a big red flag.

Other numerical effects need models for their error and uncertainty too. Linear and nonlinear error plus round-off error all can contribute to the overall uncertainty. A starting point would be the same model as the discretization error, but using the tolerances from the linear or nonlinear solution as . The starting assumption is often that these are dominated by discretization error, or tied to the discretization. Evidence in support of these assumptions is generally weak to nonexistent. For round-off errors the modeling is similar, but all of these errors can be magnified in the face of instability. A key is to provide some sort of assessment of their aggregate impact on the results and not explicitly ignore them.

Other parts of the uncertainty estimation are much more amenable to statistical structures for uncertainty. This includes the type of uncertainty that too often provides (wrongly!) the entirety of uncertainty estimation, parametric uncertainty. This problem is a direct result of the availability of tools that allow the estimation of parametric uncertainty magnitude. In addition to parametric uncertainty, random aleatory uncertainties, experimental uncertainty and deep model form uncertainty all may be examined using statistical approaches. In many ways the situation is far better than for discretization error, but in other ways the situation more dire. Things are better because statistical models can be evaluated using less data, and errors can be estimated using standard approaches. The situation is dire because often the issues being radically under-sampled are reality, not the model of reality simulations are based on.

Uncertainty is a quality to be cherished, therefore – if not for it, who would dare to undertake anything?

― Villiers de L’Isle-Adam

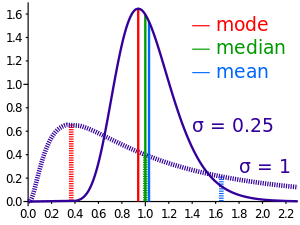

In the same way as numerical uncertainty, the first thing to decide upon is the model. A  standard modeling assumption is the use of the normal or Gaussian distribution as the starting assumption. This is almost always chosen as a default. A reasonable blog post title would be “The default probability distribution is always Gaussian”. A good thing for a distribution is that we can start to assess it beginning with two data points. A bad and common situation is that we only have a single data point. Thus uncertainty estimation is impossible without adding information from somewhere, and an expert judgment is the obvious place to look. With statistical data and its quality we can apply the standard error estimation using the sample size to scale the additional uncertainty driven by poor sampling,

standard modeling assumption is the use of the normal or Gaussian distribution as the starting assumption. This is almost always chosen as a default. A reasonable blog post title would be “The default probability distribution is always Gaussian”. A good thing for a distribution is that we can start to assess it beginning with two data points. A bad and common situation is that we only have a single data point. Thus uncertainty estimation is impossible without adding information from somewhere, and an expert judgment is the obvious place to look. With statistical data and its quality we can apply the standard error estimation using the sample size to scale the additional uncertainty driven by poor sampling, where

is the number of samples.

There are some simple ideas to apply in the case of the assumed Gaussian and a single data point. A couple of reasonable pieces of information can be added, one being an expert judged standard deviation and then by fiat making the single data point the mean of the distribution. A second assumption could be used where the mean of the distribution is defined by expert judgment, which then defines the standard deviation, |A –

where

is the defined mean, and

is the data point. In these cases the standard error estimate would be equal to

where

. Both of these approaches have the strengths and weaknesses, and include the strong assumption of the normal distribution.

In a lot of cases a better simple assumption about the statistical distribution would be to use a uniform distribution. The issue with the uniform distribution would be identifying the width of the distribution. To define the basic distribution you need at least two pieces of information just as the normal (Gaussian) distribution. The subtleties are different and need some discussion. The width of a uniform distribution is defined by –

. A question is how representative a single piece of information

would actually be? Does one center the distribution about

? One could be left with needing to add two pieces of information instead of one by defining

and

. This then allows a fairly straightforward assessment of the uncertainty.

For statistical models eventually one might resort to using a Bayesian method to encode the expert judgment in defining a prior distribution. In general terms this might seem to be an absolutely key approach to structure the expert judgment where statistical modeling is called for. The basic form of Bayes theorem is

For statistical models eventually one might resort to using a Bayesian method to encode the expert judgment in defining a prior distribution. In general terms this might seem to be an absolutely key approach to structure the expert judgment where statistical modeling is called for. The basic form of Bayes theorem is where

is the probability of

given

,

is the probability of

and so on. A great deal of the power of the method depends on having a good (or expert) handle on all the terms on the right hand side of the equation. Bayes theorem would seem to be an ideal framework for the application of expert judgment through the decision about the nature of the prior.

The mistake is thinking that there can be an antidote to the uncertainty.

― David Levithan

A key to this entire discussion is the need to resist the default uncertainty of ZERO as a principle. It would be best if real problem specific work were conducted to estimate uncertainties, the right calculations, right meshes and right experiments. If one doesn’t have the time, money or willingness, the answer is to call upon experts to fill in the gap using justifiable assumptions and information while taking an appropriate penalty for the lack of effort. This would go a long way to improving the state of practice in computational science, modeling and simulation.

Children must be taught how to think, not what to think.

― Margaret Mead

Rider, William, Walt Witkowski, James R. Kamm, and Tim Wildey. “Robust verification analysis.” Journal of Computational Physics 307 (2016): 146-163.

I have noticed that we tend to accept a phenomenally common and undeniably unfortunate practice where a failure to assess uncertainty means that the uncertainty reported (acknowledged, accepted) is identically ZERO. In other words if we do nothing at all, no work, no judgment, the work (modeling, simulation, experiment, test) is allowed to provide an uncertainty that is ZERO. This encourages scientists and engineers to continue to do nothing because this wildly optimistic assessment is a seeming benefit. If somebody does work to estimate the uncertainty the degree of uncertainty always gets larger as a result. This practice is desperately harmful to the practice and progress in science and incredibly common.

I have noticed that we tend to accept a phenomenally common and undeniably unfortunate practice where a failure to assess uncertainty means that the uncertainty reported (acknowledged, accepted) is identically ZERO. In other words if we do nothing at all, no work, no judgment, the work (modeling, simulation, experiment, test) is allowed to provide an uncertainty that is ZERO. This encourages scientists and engineers to continue to do nothing because this wildly optimistic assessment is a seeming benefit. If somebody does work to estimate the uncertainty the degree of uncertainty always gets larger as a result. This practice is desperately harmful to the practice and progress in science and incredibly common. t shortcomings, a gullible or lazy community readily accepts the incomplete work. Some of the better work has uncertainties associated with it, but almost always varying degrees of incompleteness. Of course one should acknowledge up front that uncertainty estimation is always incomplete, but the degree of incompleteness can be spellbindingly large.

t shortcomings, a gullible or lazy community readily accepts the incomplete work. Some of the better work has uncertainties associated with it, but almost always varying degrees of incompleteness. Of course one should acknowledge up front that uncertainty estimation is always incomplete, but the degree of incompleteness can be spellbindingly large.

within the expressed taxonomy for uncertainty. I’ll start with numerical uncertainty estimation that is the most commonly completely non-assessed uncertainty. Far too often a single calculation is simply shown and used without any discussion. In slightly better cases, the calculation will be given with some comments on the sensitivity of the results to the mesh and the statement that numerical errors are negligible at the mesh given. Don’t buy it! This is usually complete bullshit! In every case where no quantitative uncertainty is explicitly provided, you should be suspicious. In other cases unless the reasoning is stated as being expertise or experience it should be questioned. If it is stated as being experiential then the basis for this experience and its documentation should be given explicitly along with evidence that it is directly relevant.

within the expressed taxonomy for uncertainty. I’ll start with numerical uncertainty estimation that is the most commonly completely non-assessed uncertainty. Far too often a single calculation is simply shown and used without any discussion. In slightly better cases, the calculation will be given with some comments on the sensitivity of the results to the mesh and the statement that numerical errors are negligible at the mesh given. Don’t buy it! This is usually complete bullshit! In every case where no quantitative uncertainty is explicitly provided, you should be suspicious. In other cases unless the reasoning is stated as being expertise or experience it should be questioned. If it is stated as being experiential then the basis for this experience and its documentation should be given explicitly along with evidence that it is directly relevant. estimation. Far too many calculational efforts provide a single calculation without any idea of the requisite uncertainties. In a nutshell, the philosophy in many cases is that the goal is to complete the best single calculation possible and creating a calculation that is capable of being assessed is not a priority. In other words the value proposition for computation is either do the best single calculation without any idea of the uncertainty versus a lower quality simulation with a well-defined assessment of uncertainty. Today the best single calculation is the default approach. This best single calculation then uses the default uncertainty estimate of exactly ZERO because nothing else is done. We need to adopt an attitude that will reject this approach because of the dangers associated with accepting a calculation without any quality assessment.

estimation. Far too many calculational efforts provide a single calculation without any idea of the requisite uncertainties. In a nutshell, the philosophy in many cases is that the goal is to complete the best single calculation possible and creating a calculation that is capable of being assessed is not a priority. In other words the value proposition for computation is either do the best single calculation without any idea of the uncertainty versus a lower quality simulation with a well-defined assessment of uncertainty. Today the best single calculation is the default approach. This best single calculation then uses the default uncertainty estimate of exactly ZERO because nothing else is done. We need to adopt an attitude that will reject this approach because of the dangers associated with accepting a calculation without any quality assessment. random uncertainty. This sort of uncertainty is clearly overlooked by our modeling approach in a way that most people fail to appreciate. Our models and governing equations are oriented toward solving the average or mean solution for a given engineering or science problem. This key question is usually muddled together in modeling by adopting an approach that mixes a specific experimental event with a model focused on the average. This results in a model that has an unclear separation of the general and specific. Few experiments or events being simulated are viewed from the context that they are simply a single instantiation of a distribution of possible outcomes. The distribution of possible outcomes is generally completely unknown and not even considered. This leads to an important source of systematic uncertainty that is completely ignored.

random uncertainty. This sort of uncertainty is clearly overlooked by our modeling approach in a way that most people fail to appreciate. Our models and governing equations are oriented toward solving the average or mean solution for a given engineering or science problem. This key question is usually muddled together in modeling by adopting an approach that mixes a specific experimental event with a model focused on the average. This results in a model that has an unclear separation of the general and specific. Few experiments or events being simulated are viewed from the context that they are simply a single instantiation of a distribution of possible outcomes. The distribution of possible outcomes is generally completely unknown and not even considered. This leads to an important source of systematic uncertainty that is completely ignored. value in challenging our theory. Moreover the whole sequence of necessary activities like model development, and analysis, method and algorithm development along with experimental science and engineering are all receiving almost no attention today. These activities are absolutely necessary for modeling and simulation success along with the sort of systematic practices I’ve elaborated on in this post. Without a sea change in the attitude toward how modeling and simulation is practiced and what it depends upon, its promise as a technology will be stillborn and nullified by our collective hubris.

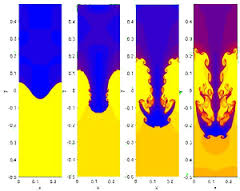

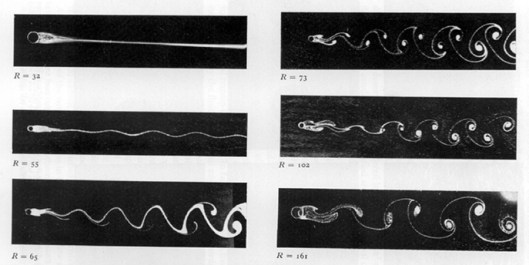

value in challenging our theory. Moreover the whole sequence of necessary activities like model development, and analysis, method and algorithm development along with experimental science and engineering are all receiving almost no attention today. These activities are absolutely necessary for modeling and simulation success along with the sort of systematic practices I’ve elaborated on in this post. Without a sea change in the attitude toward how modeling and simulation is practiced and what it depends upon, its promise as a technology will be stillborn and nullified by our collective hubris. Fluid mechanics at its simplest is something called Stokes flow, basically motion so slow that it is solely governed by viscous forces. This is the asymptotic state where the Reynolds number (the ratio of inertial to viscous forces) is identically zero. It’s a bit oxymoronic as it is never reached, it’s the equations of motion without any motion or where the motion can be ignored. In this limit flows preserve their basic symmetries to a very high degree.

Fluid mechanics at its simplest is something called Stokes flow, basically motion so slow that it is solely governed by viscous forces. This is the asymptotic state where the Reynolds number (the ratio of inertial to viscous forces) is identically zero. It’s a bit oxymoronic as it is never reached, it’s the equations of motion without any motion or where the motion can be ignored. In this limit flows preserve their basic symmetries to a very high degree. The fundamental asymmetry in physics is the arrow of time, and its close association with entropy. The connection with asymmetry and entropy is quite clear and strong for shock waves where the mathematical theory is well-developed and accepted. The simplest case to examine is Burgers’ equation,

The fundamental asymmetry in physics is the arrow of time, and its close association with entropy. The connection with asymmetry and entropy is quite clear and strong for shock waves where the mathematical theory is well-developed and accepted. The simplest case to examine is Burgers’ equation,  On the one hand the form seems to be unavoidable dimensionally, on the other it is a profound result that provides the basis of the Clay prize for turbulence. It gets to the core of my belief that to a very large degree the understanding of turbulence will elude us as long as we use the intrinsically unphysical incompressible approximation. This may seem controversial, but incompressibility is an approximation to reality, not a fundamental relation. As such its utility is dependent upon the application. It is undeniably useful, but has limits, which are shamelessly exposed by turbulence. Without viscosity the equations governing incompressible flows are pathological in the extreme. Deep mathematical analysis has been unable to find singular solutions of the nature needed to explain turbulence in incompressible flows.

On the one hand the form seems to be unavoidable dimensionally, on the other it is a profound result that provides the basis of the Clay prize for turbulence. It gets to the core of my belief that to a very large degree the understanding of turbulence will elude us as long as we use the intrinsically unphysical incompressible approximation. This may seem controversial, but incompressibility is an approximation to reality, not a fundamental relation. As such its utility is dependent upon the application. It is undeniably useful, but has limits, which are shamelessly exposed by turbulence. Without viscosity the equations governing incompressible flows are pathological in the extreme. Deep mathematical analysis has been unable to find singular solutions of the nature needed to explain turbulence in incompressible flows.

simulation is build the next generation of computers. The proposition is so shallow on the face of it as to be utterly laughable. Except no one is laughing, the programs are predicated on it. The whole mentality is damaging because it intrinsically limits our thinking about how to balance the various elements needed for progress. We see a lack of the sort of approach that can lead to progress with experimental work starved of funding and focus without the needed mathematical modeling effort necessary for utility. Actual applied mathematics has become a veritable endangered species only seen rarely in the wild.

simulation is build the next generation of computers. The proposition is so shallow on the face of it as to be utterly laughable. Except no one is laughing, the programs are predicated on it. The whole mentality is damaging because it intrinsically limits our thinking about how to balance the various elements needed for progress. We see a lack of the sort of approach that can lead to progress with experimental work starved of funding and focus without the needed mathematical modeling effort necessary for utility. Actual applied mathematics has become a veritable endangered species only seen rarely in the wild.

structures and models for average behavior. One of the key things to really straighten out is the nature of the question we are asking the model to answer. If the question isn’t clearly articulated, the model will provide deceptive answers that will send scientists and engineers in the wrong direction. Getting this model to question dynamic sorted out is far more important to the success of modeling and simulation than any advance in computing power. It is also completely and utterly off the radar of the modern research agenda. I worry that the present focus will produce damage to the forces of progress that may take decades to undue.

structures and models for average behavior. One of the key things to really straighten out is the nature of the question we are asking the model to answer. If the question isn’t clearly articulated, the model will provide deceptive answers that will send scientists and engineers in the wrong direction. Getting this model to question dynamic sorted out is far more important to the success of modeling and simulation than any advance in computing power. It is also completely and utterly off the radar of the modern research agenda. I worry that the present focus will produce damage to the forces of progress that may take decades to undue. If there is any place where singularities are dealt with systematically and properly it is fluid mechanics. Even in fluid mechanics there is a frighteningly large amount of missing territory most acutely in turbulence. The place where things really work is shock waves and we have some very bright people to thank for the order. We can calculate an immense amount of physical phenomena where shock waves are important while ignoring a tremendous amount of detail. All that matter is for the calculation to provide the appropriate integral content of dissipation from the shock wave, and the calculation is wonderfully stable and physical. It is almost never necessary and almost certainly wasteful to compute the full gory details of a shock wave.

If there is any place where singularities are dealt with systematically and properly it is fluid mechanics. Even in fluid mechanics there is a frighteningly large amount of missing territory most acutely in turbulence. The place where things really work is shock waves and we have some very bright people to thank for the order. We can calculate an immense amount of physical phenomena where shock waves are important while ignoring a tremendous amount of detail. All that matter is for the calculation to provide the appropriate integral content of dissipation from the shock wave, and the calculation is wonderfully stable and physical. It is almost never necessary and almost certainly wasteful to compute the full gory details of a shock wave. y to progress. I believe the issue is the nature of the governing equations and a need to change this model away from incompressibility, which is a useful and unphysical approximation, not a fundamental physical law. In spite of all the problems, the state of affairs in turbulence is remarkably good compared with solid mechanics.

y to progress. I believe the issue is the nature of the governing equations and a need to change this model away from incompressibility, which is a useful and unphysical approximation, not a fundamental physical law. In spite of all the problems, the state of affairs in turbulence is remarkably good compared with solid mechanics. An example of lower mathematical maturity can be seen in the field of solid mechanics. In solids, the mathematical theory is stunted by comparison to fluids. A clear part of the issue is the approach taken by the fathers of the field in not providing a clear path for combined analytical-numerical analysis as fluids had. The result of this is a numerical background that is completely left adrift of the analytical structure of the equations. In essence the only option is to fully resolve everything in the governing equations. No structural and systematic explanation exists for the key singularities in material, which is absolutely vital for computational utility. In a nutshell the notion of the regularized singularity so powerful in fluid mechanics is foreign. This has a dramatically negative impact on the capacity of modeling and simulation to have a maximal impact.

An example of lower mathematical maturity can be seen in the field of solid mechanics. In solids, the mathematical theory is stunted by comparison to fluids. A clear part of the issue is the approach taken by the fathers of the field in not providing a clear path for combined analytical-numerical analysis as fluids had. The result of this is a numerical background that is completely left adrift of the analytical structure of the equations. In essence the only option is to fully resolve everything in the governing equations. No structural and systematic explanation exists for the key singularities in material, which is absolutely vital for computational utility. In a nutshell the notion of the regularized singularity so powerful in fluid mechanics is foreign. This has a dramatically negative impact on the capacity of modeling and simulation to have a maximal impact. Being thrust into a leadership position at work has been an eye-opening experience to say the least. It makes crystal clear a whole host of issues that need to be solved. Being a problem-solver at heart, I’m searching for a root cause for all the problems that I see. One can see the symptoms all around, poor understanding, poor coordination, lack of communication, hidden agendas, ineffective vision, and intellectually vacuous goals… I’ve come more and more to the view that all of these things, evident as the day is long are simply symptomatic of a core problem. The core problem is a lack of trust so broad and deep that it rots everything it touches.

Being thrust into a leadership position at work has been an eye-opening experience to say the least. It makes crystal clear a whole host of issues that need to be solved. Being a problem-solver at heart, I’m searching for a root cause for all the problems that I see. One can see the symptoms all around, poor understanding, poor coordination, lack of communication, hidden agendas, ineffective vision, and intellectually vacuous goals… I’ve come more and more to the view that all of these things, evident as the day is long are simply symptomatic of a core problem. The core problem is a lack of trust so broad and deep that it rots everything it touches. on the whole of society leeches. They claim to be helping society even while they damage our future to feed their hunger. The deeper physic wound is the feeling that everyone is so motivated leading to the broad-based lack of trust of your fellow man.

on the whole of society leeches. They claim to be helping society even while they damage our future to feed their hunger. The deeper physic wound is the feeling that everyone is so motivated leading to the broad-based lack of trust of your fellow man. In the overall execution of work another aspect of the current environment can be characterized as the proprietary attitude. Information hiding and lack of communication seem to be a growing problem even as the capacity for transmitting information grows. Various legal, or political concerns seem to outweigh the needs for efficiency, progress and transparency. Today people seem to know much less than they used to instead of more. People are narrower and more tactical in their work rather than broader and strategic. We are encouraged to simply mind our own business rather than seek a broader attitude. The thing that really suffers in all of this is the opportunity to make progress for a better future.

In the overall execution of work another aspect of the current environment can be characterized as the proprietary attitude. Information hiding and lack of communication seem to be a growing problem even as the capacity for transmitting information grows. Various legal, or political concerns seem to outweigh the needs for efficiency, progress and transparency. Today people seem to know much less than they used to instead of more. People are narrower and more tactical in their work rather than broader and strategic. We are encouraged to simply mind our own business rather than seek a broader attitude. The thing that really suffers in all of this is the opportunity to make progress for a better future. The simplest thing to do is value the truth, value excellence and cease rewarding the sort of trust-busting actions enumerated above. Instead of allowing slip-shod work to be reported as excellence we need to make strong value judgments about the quality of work, reward excellence, and punish incompetence. The truth and fact needs to be valued above lies and spin. Bad information needs to be identified as such and eradicated without mercy. Many greedy self-interested parties are strongly inclined to seed doubt and push lies and spin. The battle is for the nature of society. Do we want to live in a World of distrust and cynicism or one of truth and faith in one another? The balance today is firmly stuck at distrust and cynicism. The issue of excellence is rather pregnant. Today everyone is an expert, and no one is an expert with the general notion of expertise being highly suspected. The impact of such a milieu is absolutely damaging to the structure of society and the prospects for progress. We need to seed, reward and nurture excellence across society instead of doubting and demonizing it.

The simplest thing to do is value the truth, value excellence and cease rewarding the sort of trust-busting actions enumerated above. Instead of allowing slip-shod work to be reported as excellence we need to make strong value judgments about the quality of work, reward excellence, and punish incompetence. The truth and fact needs to be valued above lies and spin. Bad information needs to be identified as such and eradicated without mercy. Many greedy self-interested parties are strongly inclined to seed doubt and push lies and spin. The battle is for the nature of society. Do we want to live in a World of distrust and cynicism or one of truth and faith in one another? The balance today is firmly stuck at distrust and cynicism. The issue of excellence is rather pregnant. Today everyone is an expert, and no one is an expert with the general notion of expertise being highly suspected. The impact of such a milieu is absolutely damaging to the structure of society and the prospects for progress. We need to seed, reward and nurture excellence across society instead of doubting and demonizing it. Ultimately we need to conscientiously drive for trust as a virtue in how we approach each other. A big part of trust is the need for truth in our communication. The sort of lying, spinning and bullshit in communication does nothing but undermine trust, and empower low quality work. We need to empower excellence through our actions rather than simply declare things to be excellent by definition and fiat. Failure is a necessary element in achievement and expertise. It must be encouraged. We should promote progress and quality as a necessary outcome across the broadest spectrum of work. Everything discussed above needs to be based in a definitive reality and have actual basis in facts instead of simply bullshitting about it, or it only having “truthiness”. Not being able to see the evidence of reality in claims of excellence and quality simply amplifies the problems with trust, and risks devolving into a viscous cycle dragging us down instead of a virtuous cycle that lifts us up.

Ultimately we need to conscientiously drive for trust as a virtue in how we approach each other. A big part of trust is the need for truth in our communication. The sort of lying, spinning and bullshit in communication does nothing but undermine trust, and empower low quality work. We need to empower excellence through our actions rather than simply declare things to be excellent by definition and fiat. Failure is a necessary element in achievement and expertise. It must be encouraged. We should promote progress and quality as a necessary outcome across the broadest spectrum of work. Everything discussed above needs to be based in a definitive reality and have actual basis in facts instead of simply bullshitting about it, or it only having “truthiness”. Not being able to see the evidence of reality in claims of excellence and quality simply amplifies the problems with trust, and risks devolving into a viscous cycle dragging us down instead of a virtuous cycle that lifts us up.