In our attempt to make conservation easy, we have made it trivial.

― Aldo Leopold

The reality is that it may or may not matter that the Chinese are cleaning the floor with us in supercomputing. Whether it matters comes down to some details dutifully ignored by the news articles. Unfortunately, those executing our supercomputing programs ignorantly ignore these same details. In these details we can find the determining factors of whether the Chinese hardware supremacy is a sign that they are really beating the USA where it matters. Supercomputing is only important because of modeling & simulation, which depends on a massive swath of scientific endeavor to faithfully achieve. The USA’s national supercomputing program is starving this swath of scientific competence in order to build the fastest supercomputer. If the Chinese are simultaneously investing in computing hardware and the underlying science of modeling & simulation, they will win. Without the underlying science no amount of achievement in computing power will be provide victory. The source of the ignorance in our execution of a supercomputing program is a combination of willful ignorance, and outright incompetence. In terms of damage the two are virtually indistinguishable.

There is nothing more frightful than ignorance in action.

― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

The news last w eek was full of the USA’s continued losing streak to Chinese supercomputers. Their degree of supremacy is only growing and now the Chinese have more machines on the list of top high performance computers than the USA. Perhaps as importantly the Chinese didn’t relied on homegrown computer hardware rather than on the USA’s. One could argue that American export law cost them money, but also encouraged them to build their own. So is this a failure or success of the policy, or a bit of both. Rather than panic, maybe its time to admit that it doesn’t really matter. Rather than offer a lot of concern we should start a discussion about how meaningful it actually is. If the truth is told it isn’t very important at all.

eek was full of the USA’s continued losing streak to Chinese supercomputers. Their degree of supremacy is only growing and now the Chinese have more machines on the list of top high performance computers than the USA. Perhaps as importantly the Chinese didn’t relied on homegrown computer hardware rather than on the USA’s. One could argue that American export law cost them money, but also encouraged them to build their own. So is this a failure or success of the policy, or a bit of both. Rather than panic, maybe its time to admit that it doesn’t really matter. Rather than offer a lot of concern we should start a discussion about how meaningful it actually is. If the truth is told it isn’t very important at all.

If we too aggressively pursue regaining the summit of this list we may damage the part of supercomputing that actually does matter. Furthermore what we aren’t discussing is the relative positions of the Chinese to the Americans (or the Europeans for that matter) in the part of computing that does matter: modeling & simulation. Modeling and simulation is the real reason we do computing and the value in it is not measured or defined by computing hardware. Granted that computer hardware plays a significant role in the overall capacity to conduct simulations, but is not even the dominant player in modeling effectiveness. Worse yet, in the process of throwing all our effort behind getting the fastest hardware, we are systematically undermining the parts of supercomputing that add real value and have far greater importance. Underlying this assessment is the conclusion that our current policy isn’t based on what is important and supports a focus on less important aspects of the field that simply are more explicable to lay people.

If we too aggressively pursue regaining the summit of this list we may damage the part of supercomputing that actually does matter. Furthermore what we aren’t discussing is the relative positions of the Chinese to the Americans (or the Europeans for that matter) in the part of computing that does matter: modeling & simulation. Modeling and simulation is the real reason we do computing and the value in it is not measured or defined by computing hardware. Granted that computer hardware plays a significant role in the overall capacity to conduct simulations, but is not even the dominant player in modeling effectiveness. Worse yet, in the process of throwing all our effort behind getting the fastest hardware, we are systematically undermining the parts of supercomputing that add real value and have far greater importance. Underlying this assessment is the conclusion that our current policy isn’t based on what is important and supports a focus on less important aspects of the field that simply are more explicable to lay people.

Let’s take this argument apart and get to the heart of why the current narrative in supercomputing is so completely and utterly off base. Worse than a bad narrative, the current mindset is leading to bad decisions and terrible investments that will set back science and diminish the power and scope of modeling & simulation to be transformative in today’s world. It is a reasonable concern that the reaction of the powers that be to the Chinese “success” in hardware will be to amplify the already terrible decisions in research and investment strategy.

The real heart of the matter is that the Chinese victory in supercomputing power is pretty meaningless. The computer they’ve put at the top of the list is close to practically useless, and wins at computing a rather poorly chosen benchmark problem. This benchmark problem was never a particularly good measure of supercomputers, and the gap between the real reasons for buying such computers, the efficacy of the benchmark has only grown more vast over the years. It is not the absolute height of ridiculousness that anyone even cares, but care we do. The benchmark computes the LU decomposition of a dense matrix, a classical linear algebra problem computed at a huge scale. It is simply wildly uncharacteristic of the problems and codes we buy supercomputers to solve. It skews the point of view in directions that are unremittingly negative, and ends up helping to drive lousy investments.

We have set about a serious program to recapture the supercomputing throne. In its wake we will do untold amounts of damage to the future of modeling & simulation. We are in the process of spending huge sums of money chasing a summit that does not matter at all. In the process we will starve the very efforts that could allow us to unleash the full power of the science and engineering capability we should be striving for. A capability that would have massively positive impacts on all of the things supercomputing is supposed to contribute toward. The entire situation is patently absurd, and tragic. It is ironic that those who act to promote high performance computing are killing it. They are killing it because they fail to understand it or how science actually works.

We have set about a serious program to recapture the supercomputing throne. In its wake we will do untold amounts of damage to the future of modeling & simulation. We are in the process of spending huge sums of money chasing a summit that does not matter at all. In the process we will starve the very efforts that could allow us to unleash the full power of the science and engineering capability we should be striving for. A capability that would have massively positive impacts on all of the things supercomputing is supposed to contribute toward. The entire situation is patently absurd, and tragic. It is ironic that those who act to promote high performance computing are killing it. They are killing it because they fail to understand it or how science actually works.

Let’s get a couple of truths out there to consider:

- There is no amount of computer speed, nor solution accuracy or algorithmic efficiency that can rescue a model that is incorrect.

- The best methods produce the ability to solve problems that were impossible before. Sometimes methods & models blur together producing a merged capability that transcends the normal distinctions providing ability to solve problems in ways not previously imagined.

- Algorithmic efficiency coupled with modeling improvements and methods allows solutions to proceed with efficiency that goes well beyond mere multiples in efficiency; the gains are geometric or exponential in character.

- The improvements in these three arenas all have historically vastly out-paced the improvements associated with computer hardware.

The tragedy is that these four areas are almost completely ignored by our current high-performance computing program. The current program is basically porting legacy code and doing little else. Again, we have to acknowledge that a great deal of work is being done to enable the porting of codes to succeed. This is in the area of genuinely innovative computer science research and methodology to allow easier programming of these monstrous computers we are building.

On the other hand, we have so little faith in the power of our imaginations and capacity for innovation that we will not take the risk of relying on these forces for progress. Declaring that the current approach is cowardly is probably a bit over the top, but not by much. I will declare that it is unequivocally anti-intellectual and based upon simple-minded conclusions about the power, value and source of computing’s impact on science and society. Simple is good and elegant, but simple-minded is not. The simple-minded approach does a great disservice to all of us.

Any darn fool can make something complex; it takes a genius to make something simple.

― Pete Seeger

The single most important thing in modeling & simulation is the nature of the model itself. The model contains the entirety of the capacity of the rest of the simulation to reproduce reality. In looking at HPC today any effort to improve models is utterly and completely lacking. Next in importance are the methods that solve those models, and again we see no effort at all in developing better methods. Next we have algorithms whose character determines the efficiency of solution, and again the efforts to improve this character are completely absent. With algorithms we start to see some effort, but only in the service of implementing existing ones on the new computers. Next in importance comes code and system software and here we see significant effort. The effort is to move old codes onto new computers, and produce software systems that unveil the power of new computers to some utility. Last and furthest from importance is the hardware. Here, we see the greatest degree of focus. In the final analysis we see the greatest focus, money and energy on those things that matter least. It is the makings of a complete disaster, and a disaster of our own making.

The single most important thing in modeling & simulation is the nature of the model itself. The model contains the entirety of the capacity of the rest of the simulation to reproduce reality. In looking at HPC today any effort to improve models is utterly and completely lacking. Next in importance are the methods that solve those models, and again we see no effort at all in developing better methods. Next we have algorithms whose character determines the efficiency of solution, and again the efforts to improve this character are completely absent. With algorithms we start to see some effort, but only in the service of implementing existing ones on the new computers. Next in importance comes code and system software and here we see significant effort. The effort is to move old codes onto new computers, and produce software systems that unveil the power of new computers to some utility. Last and furthest from importance is the hardware. Here, we see the greatest degree of focus. In the final analysis we see the greatest focus, money and energy on those things that matter least. It is the makings of a complete disaster, and a disaster of our own making.

…the commercially available and laboratory technologies are inadequate for the stockpile stewardship tasks we will face in the future. Another hundred-to-thousand-fold increase in capability from hardware and software combined will be required… Some aspects of nuclear explosive design are still not understood at the level of physical principles…

–C. Paul Robinson, in testimony to the House National Security Committee on May 12, 1996

It is instructive to examine where these decisions came from whether they made sense at one time and still do today. The harbinger of the current exascale initiative was the ASC(I) program created in the wake of the end of nuclear testing in the early 1990’s. The ASC(I) program was based on a couple of predicates: computational simulation would replace full scale testing, and that computational speed was central to success. When nuclear tested ceased the Cray vector supercomputers provided the core of modeling & simulation computer capability. The prevailing wisdom that the combination of massively parallel computing and Moore’s law for commodity chips would win. This was the “Attack of the Killer Micros” (http://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/06/business/the-attack-of-the-killer-micros.html?pagewanted=all). I would submit that these premises were correct to some degree, but also woefully incomplete. Some of these shortcomings have been addressed in the broader stockpile stewardship program albeit poorly. Major experimental facilities and work was added to the original program, which has provided vastly more balanced scientific content to the endeavor. While more balanced, the overall program is still unbalanced with too much emphasis on computing as defined by raw computational power, with too little emphasis on theory (models), methods and algorithms along with an overly cautious and generally underfunded experimental program.

On the modeling & simulation side many of the balance issues were attacked by rather tepid efforts adding some modeling, and methods work. Algorithmic innovation has been largely limited to the monumental task of moving existing algorithms to massively parallel computers. The result has been a relative dearth of algorithmic innovations and increasingly high levels of technical debt and inflation permeating the code base. The modeling work is almost entirely based on closing existing systems of equations used to create models without any real focus on the propriety of the equations themselves. This is exacerbated by the cautious and underfunded experimental efforts that fail to challenge the equations in any fundamental way. We can look at public failures like NIF as being emblematic of the sort of problems we are creating for ourselves. We will not compute our way out of a problem like NIF!

The important thing about ASC(I) is that it created a model of successfully funding a program. As such, it became the go-to model for developing a new program, and the blueprint for our exascale program. Judging from the exascale program’s design and execution, it has learned little or nothing from the ASC(I) program’s history aside from the lesson of how to get something funded. The overall effort actually represents a sharp step backward by failing to implement any of the course corrections ASC(I) made relatively early in its life. The entirety of the lessons from ASC(I) were simply the recipe for getting money, which to put it plainly is “focus all the attention on the computers”. Everything else is a poorly thought through afterthought, largely consisting of a wealth of intellectually empty activities that look like relatively sophisticated code porting exercises (and some aren’t that sophisticated).

The price for putting such priority and importance on the trivial is rather high. We are creating an ecosystem that will strangle progress in its crib. As an ecosystem we have failed to care for the essential “apex” predators. By working steadfastly toward supremacy in the trivial we starve the efforts that would yield true gains and actual progress. Yet this is what we do, it has become a matter of policy. We have gotten here because those we have entrusted with creating the path forward don’t know what they are doing. They have allowed their passion for computer hardware to overwhelm their duties and their training as scientists. They have allowed a trivial and superficial understanding of modeling & simulation to rule the creation of the programs for sustaining progress. They have allowed the needs of marketing a program to overwhelm the duty to make those programs coherent and successful. It is a tragedy we see playing out society-wide.

Our current approach to advancing high performance computing is completely superficial. Rather than focus on the true measure of value being modeling & simulation, we focus on computing hardware to an unhealthy degree. Modeling & simulation is the activity where we provide a capability to change our reality, or our knowledge of reality. It is a holistic activity relying upon the full chain of competencies elaborated upon above. If anything in this chain fails, the entire activity fails. Computing hardware is absolutely essential and necessary. Progress via faster computers is welcome, but we fail to acknowledge its relative importance in the chain. In almost every respect it is the furthest away from impacting reality, while more essential parts of the overall capability are starved for resources and ignored. Perhaps more pointedly, the time for focus on hardware has passed as Moore’s law is dead and buried. Much of the current hardware focus is a futile attempt to breathe life into this increasingly cold and rigid corpse. Instead we should be looking at this moment in time as an opportunity (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/01/15/could-the-demise-of-moores-law-be-a-blessing-in-disguise/). The demise of Moore’s law was actual a blessing that unleashed a torrent of innovative energy we are still reeling from today.

It is time to focus our collective creative and innovative energy where opportunity exists. For example, the arena of algorithmic innovation has been a more fertile and productive route to improving the performance of modeling& simulation than hardware. The evidence for this source of progress is vast and varied; I’ve written on it on several occasions (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2014/02/28/why-algorithms-and-modeling-beat-moores-law/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2015/02/14/not-all-algorithm-research-is-created-equal/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2015/05/29/focusing-on-the-right-scaling-is-essential/). Despite this, we put little or no effort in this demonstrably productive direction. For example many codes rely desperately on numerical linear algebra algorithms. These algorithms have a massive impact on the efficiency of the modeling & simulation often being enabling. Yet we have seen no fundamental breakthroughs in the field for over 30 years. Perhaps there aren’t any further breakthroughs to be made, but this is a far too pessimistic outlook on the capacity of humans to create, innovate and discover solutions to important problems.

It is time to focus our collective creative and innovative energy where opportunity exists. For example, the arena of algorithmic innovation has been a more fertile and productive route to improving the performance of modeling& simulation than hardware. The evidence for this source of progress is vast and varied; I’ve written on it on several occasions (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2014/02/28/why-algorithms-and-modeling-beat-moores-law/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2015/02/14/not-all-algorithm-research-is-created-equal/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2015/05/29/focusing-on-the-right-scaling-is-essential/). Despite this, we put little or no effort in this demonstrably productive direction. For example many codes rely desperately on numerical linear algebra algorithms. These algorithms have a massive impact on the efficiency of the modeling & simulation often being enabling. Yet we have seen no fundamental breakthroughs in the field for over 30 years. Perhaps there aren’t any further breakthroughs to be made, but this is a far too pessimistic outlook on the capacity of humans to create, innovate and discover solutions to important problems.

There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there has always been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that ‘my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.

― Isaac Asimov

All of this gets at a far more widespread and dangerous societal issue; we are incapable of dealing with any issue that is complex and technical. Increasingly we have no tolerance for anything where expert judgment is necessary. Science and scientists are increasingly being dismissed when their messaging is unpleasant or difficult to take. Examples abound with last week’s Brexit easily coming to mind, and climate change providing an ongoing example of willful ignorance. Talking about how well we or anyone else does modeling & simulation is subtle and technical. As everyone should be well aware subtle and technical arguments and discussions are not possible in the public sphere. As a result we are left with horrifically superficial measures such as raw supercomputing power as measured by a meaningless, but accepted benchmark. The result is a harvest of immense damage to actual capability and investment in a strategy that does very little to improve matters. We are left with a hopelessly ineffective high performance-computing program that wastes sums of money; entire careers and will in all likelihood result in a real loss of National supremacy in modeling & simulation.

All of this gets at a far more widespread and dangerous societal issue; we are incapable of dealing with any issue that is complex and technical. Increasingly we have no tolerance for anything where expert judgment is necessary. Science and scientists are increasingly being dismissed when their messaging is unpleasant or difficult to take. Examples abound with last week’s Brexit easily coming to mind, and climate change providing an ongoing example of willful ignorance. Talking about how well we or anyone else does modeling & simulation is subtle and technical. As everyone should be well aware subtle and technical arguments and discussions are not possible in the public sphere. As a result we are left with horrifically superficial measures such as raw supercomputing power as measured by a meaningless, but accepted benchmark. The result is a harvest of immense damage to actual capability and investment in a strategy that does very little to improve matters. We are left with a hopelessly ineffective high performance-computing program that wastes sums of money; entire careers and will in all likelihood result in a real loss of National supremacy in modeling & simulation.

All of this to avoid having a conversation of substance about what might constitute our actual capability. All to avoid having to invest effort in a holistic strategy that might produce actual advances. It is a problem that is repeated over and over in our National conversations due to the widespread distrust of expertise and intellect. In the end the business interests in computing highjack the dialog and we default to a “business” friendly program that is basically a giveaway. Worse yet, we buy into the short-term time scales for business and starve the long-term health of the entire field.

One of the early comments on this post took note of the display of “healthy skepticism”. While I believe that healthy skepticism is warranted, to call my point-of-view skeptical understates my position rather severely. I am severely critical. I am appalled by the utter and complete lack of thought going into this program. I realize that what I feel is not skepticism, but rather contempt. I see the damage being done by our approach every single day. The basis of the current push for exascale lacks virtually any rigor or depth of thought. It is based on misunderstanding science, and most egregiously the science it is supposed to be supporting. We have defaulted to a simple-minded argument because we think we can get money using it. We are not relying on a simple argument, but simple-minded argument. The simple argument is that modeling & simulation is vital to our security economic or military. The simple-minded argument we are following is a real and present threat to what really matters.

More posts related to this topic:

https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2014/12/08/the-unfinished-business-of-modeling-simulation/

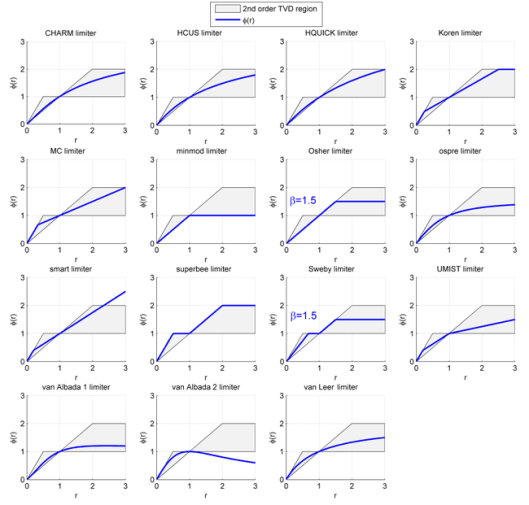

A key part of the first generation’s methods success was the systematic justification for the form of limiters via a deep mathematical theory. This was introduced by Ami Harten with his total variation diminishing (TVD) methods. This nice structure for limiters and proofs of the non-oscillatory property really allowed these methods to take off. To amp things up even more, Sweby did some analysis and introduced a handy diagram to visualize the limiter and determine simply whether it fit the bill for being a monotone limiter. The theory builds upon some earlier work of Harten that showed how upwind methods provided a systematic basis for reliable computation through vanishing viscosity.

A key part of the first generation’s methods success was the systematic justification for the form of limiters via a deep mathematical theory. This was introduced by Ami Harten with his total variation diminishing (TVD) methods. This nice structure for limiters and proofs of the non-oscillatory property really allowed these methods to take off. To amp things up even more, Sweby did some analysis and introduced a handy diagram to visualize the limiter and determine simply whether it fit the bill for being a monotone limiter. The theory builds upon some earlier work of Harten that showed how upwind methods provided a systematic basis for reliable computation through vanishing viscosity. he TVD and monotonicity-preserving methods while reliable and tunable through these functional relations have serious shortcomings. These methods have serious limitations in accuracy especially near detailed features in solutions. These detailed structures are significantly degraded because the methods based on these principles are only first-order accurate in these areas basically being upwind differencing. In mathematical terms this means that the solution are first-order in the L-infinity norm, approximately one-and-a-half in the L-2 (energy) norm and second-order in the L1 norm. The L1 norm is natural for shocks so it isn’t a complete disaster. While this class of method is vastly better than their linear predecessors effectively providing solutions completely impossible before, the methods are imperfect. The desire is to remove the accuracy limitations of these methods especially to avoid degradation of features in the solution.

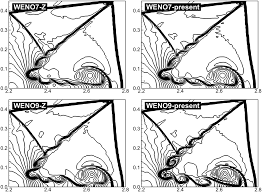

he TVD and monotonicity-preserving methods while reliable and tunable through these functional relations have serious shortcomings. These methods have serious limitations in accuracy especially near detailed features in solutions. These detailed structures are significantly degraded because the methods based on these principles are only first-order accurate in these areas basically being upwind differencing. In mathematical terms this means that the solution are first-order in the L-infinity norm, approximately one-and-a-half in the L-2 (energy) norm and second-order in the L1 norm. The L1 norm is natural for shocks so it isn’t a complete disaster. While this class of method is vastly better than their linear predecessors effectively providing solutions completely impossible before, the methods are imperfect. The desire is to remove the accuracy limitations of these methods especially to avoid degradation of features in the solution. A big part of understanding the issues with ENO comes down to how the method works. The approximation is made through hierarchically selecting the smoothest approximation (in some sense) for each order and working ones way to high-order. In this way the selection of the second-order term is dependent on the first-order term, and the third-order term is dependent on the selected second-order term, the fourth-order term on the third-order one,… This makes the ENO method subject to small variations in the data, and prey to pathological data. For example the data could be chosen so that the linearly unstable stencil is preferentially chosen leading to nasty solutions. The safety of the relatively smooth and dissipative method makes up for these dangers. Still these problems resulted in the creation of the weighted ENO (WENO) methods that have basically replaced ENO for all intents and purposes.

A big part of understanding the issues with ENO comes down to how the method works. The approximation is made through hierarchically selecting the smoothest approximation (in some sense) for each order and working ones way to high-order. In this way the selection of the second-order term is dependent on the first-order term, and the third-order term is dependent on the selected second-order term, the fourth-order term on the third-order one,… This makes the ENO method subject to small variations in the data, and prey to pathological data. For example the data could be chosen so that the linearly unstable stencil is preferentially chosen leading to nasty solutions. The safety of the relatively smooth and dissipative method makes up for these dangers. Still these problems resulted in the creation of the weighted ENO (WENO) methods that have basically replaced ENO for all intents and purposes. WENO gets rid of the biggest issues with ENO by making the approximation much less sensitive to small variations in the data, and biasing the selection toward more numerically stable approximations. Moreover the solution to these issues allows for an even higher order approximation to be used if the solution is smooth enough to allow this. Part of the issue is the nature of ENO’s approach to approximation. ENO is focused on diminishing the dissipation at extrema, but systematically creates lower fidelity approximations everywhere else. If one looks at TVD approximations the “limiters” have a lot of room for non-oscillatory solutions if the solution is locally monotone. This is part of the power of these methods allowing great fidelity in regions away from extrema. By not capitalizing on this foundation, the ENO methods failed to build on the TVD foundation successfully. WENO methods come closer, but still produce far too much dissipation and too little fidelity to fully replace monotonicity-preservation in practical calculations. Nonetheless ENO and WENO methods are pragmatically and empirically known to be nonlinearly stable methods.

WENO gets rid of the biggest issues with ENO by making the approximation much less sensitive to small variations in the data, and biasing the selection toward more numerically stable approximations. Moreover the solution to these issues allows for an even higher order approximation to be used if the solution is smooth enough to allow this. Part of the issue is the nature of ENO’s approach to approximation. ENO is focused on diminishing the dissipation at extrema, but systematically creates lower fidelity approximations everywhere else. If one looks at TVD approximations the “limiters” have a lot of room for non-oscillatory solutions if the solution is locally monotone. This is part of the power of these methods allowing great fidelity in regions away from extrema. By not capitalizing on this foundation, the ENO methods failed to build on the TVD foundation successfully. WENO methods come closer, but still produce far too much dissipation and too little fidelity to fully replace monotonicity-preservation in practical calculations. Nonetheless ENO and WENO methods are pragmatically and empirically known to be nonlinearly stable methods. Given the lack of success of the second generation of methods, we have a great need for a third generation of nonlinear methods that might displace the TVD methods. Part of the issue with the ENO methods is the lack of a strict set of constraints to guide the development of the methods. While WENO methods also lack such constraints, they do have a framework that allows for design through the construction of the smoothness sensors, which help to determine the weights of the scheme. It allows for a lot of creativity, but the basic framework still leads to too much loss of fidelity compared to TVD methods. When one measures the accuracy of real solutions to practical problems WENO still has difficulty being competitive with TVD–don’t fooled by comparisons that show WENO being vastly better than TVD, the TVD method chosen to compare with is absolute shit. A good TVD method is very competitive, so the comparison is frankly disingenuous. For this reason something better is needed or progress will continue to stall.

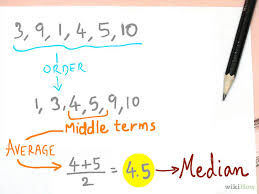

Given the lack of success of the second generation of methods, we have a great need for a third generation of nonlinear methods that might displace the TVD methods. Part of the issue with the ENO methods is the lack of a strict set of constraints to guide the development of the methods. While WENO methods also lack such constraints, they do have a framework that allows for design through the construction of the smoothness sensors, which help to determine the weights of the scheme. It allows for a lot of creativity, but the basic framework still leads to too much loss of fidelity compared to TVD methods. When one measures the accuracy of real solutions to practical problems WENO still has difficulty being competitive with TVD–don’t fooled by comparisons that show WENO being vastly better than TVD, the TVD method chosen to compare with is absolute shit. A good TVD method is very competitive, so the comparison is frankly disingenuous. For this reason something better is needed or progress will continue to stall. The median is what a lot of people think of when you say “household income”. It is a statistical measure of central tendency of data that is a harder to compute alternative to the friendly common mean value. For large data sets the median is tedious and difficult to compute while the mean is straightforward and easy. The median is the middle entry of the ordered list of numerical data thus the data being studied needs to be ordered, which is hard and expensive to perform. The mean of the data is simple to compute. On the other hand by almost any rational measure, the median is better than the mean. For one thing, the median is not easily corrupted by any outliers in the data (data that is inconsistent or corrupted); it quite effectively ignores them. The same outliers immediately and completely corrupt the mean. The median is strongly associated with the one-norm, which is completely awesome and magical.

The median is what a lot of people think of when you say “household income”. It is a statistical measure of central tendency of data that is a harder to compute alternative to the friendly common mean value. For large data sets the median is tedious and difficult to compute while the mean is straightforward and easy. The median is the middle entry of the ordered list of numerical data thus the data being studied needs to be ordered, which is hard and expensive to perform. The mean of the data is simple to compute. On the other hand by almost any rational measure, the median is better than the mean. For one thing, the median is not easily corrupted by any outliers in the data (data that is inconsistent or corrupted); it quite effectively ignores them. The same outliers immediately and completely corrupt the mean. The median is strongly associated with the one-norm, which is completely awesome and magical.  This connection is explored through the amazing and useful field of compressed sensing, which uses the one norm to do some really sweet (cool, awesome, spectacular, …) stuff.

This connection is explored through the amazing and useful field of compressed sensing, which uses the one norm to do some really sweet (cool, awesome, spectacular, …) stuff. The same basic recipe of bounding allows the parabolic limiter for the PPM method to be expressed quite concisely and clearly. The classic version of the PPM limiter involves “if” statements and seems rather unintuitive. With the median it is very clear and concise. The first simply assures that the chosen (high-order) edge values,

The same basic recipe of bounding allows the parabolic limiter for the PPM method to be expressed quite concisely and clearly. The classic version of the PPM limiter involves “if” statements and seems rather unintuitive. With the median it is very clear and concise. The first simply assures that the chosen (high-order) edge values,  This produced a concept of producing nonlinear schemes that I originally defined as a “playoff” system. The best accurate and stable approximation would be the champion of the playoffs and would inherit the properties of the set of schemes used to construct the playoff. This would work as long as the playoff was properly orchestrated to produce stable and high-order approximations in a careful manner if the median were used to settle the competition. I had discussed this as a way to produce better ENO-like schemes. Perhaps I should have taken the biological analogy in the definition of the scheme in terms of what sort of offspring each decision point in the scheme bred. Here the median is used to breed the schemes and produce more fit offspring. The goal at the end of scheme is to produce an approximation with a well-chosen order of accuracy and stability that can be proven.

This produced a concept of producing nonlinear schemes that I originally defined as a “playoff” system. The best accurate and stable approximation would be the champion of the playoffs and would inherit the properties of the set of schemes used to construct the playoff. This would work as long as the playoff was properly orchestrated to produce stable and high-order approximations in a careful manner if the median were used to settle the competition. I had discussed this as a way to produce better ENO-like schemes. Perhaps I should have taken the biological analogy in the definition of the scheme in terms of what sort of offspring each decision point in the scheme bred. Here the median is used to breed the schemes and produce more fit offspring. The goal at the end of scheme is to produce an approximation with a well-chosen order of accuracy and stability that can be proven. One of the most important things about modern computational methods is their nonlinear approach to solving problems. These methods are easily far more important to the utility of modeling and simulation in the modern world than high performance computing. The sad thing is that little or no effort is going into extending and improving these approaches despite the evidence of their primacy. Our current investments in hardware are unlikely to yield much improvement whereas these methods were utterly revolutionary in their impact. The lack of perspective regarding this reality is leading to vast investment in computing technology that will provide minimal returns.

One of the most important things about modern computational methods is their nonlinear approach to solving problems. These methods are easily far more important to the utility of modeling and simulation in the modern world than high performance computing. The sad thing is that little or no effort is going into extending and improving these approaches despite the evidence of their primacy. Our current investments in hardware are unlikely to yield much improvement whereas these methods were utterly revolutionary in their impact. The lack of perspective regarding this reality is leading to vast investment in computing technology that will provide minimal returns. that have powered computational physics into a powerful technology. Without these methods we would not have the capacity to reliably simulate many scientifically interesting and important problems, or utilize simulation in the conduct of engineering. The epitome of modeling and simulation success is computational fluid dynamics (CFD) where these nonlinear methods have provided the robust stability and stunning results capturing imaginations. In CFD these methods were utterly game changing and the success of the entire field is predicated on their power. The key to this power is poorly understood, and too often credited to computing hardware instead of the real source of progress: models, methods and algorithms with the use of nonlinear discretizations being primal.

that have powered computational physics into a powerful technology. Without these methods we would not have the capacity to reliably simulate many scientifically interesting and important problems, or utilize simulation in the conduct of engineering. The epitome of modeling and simulation success is computational fluid dynamics (CFD) where these nonlinear methods have provided the robust stability and stunning results capturing imaginations. In CFD these methods were utterly game changing and the success of the entire field is predicated on their power. The key to this power is poorly understood, and too often credited to computing hardware instead of the real source of progress: models, methods and algorithms with the use of nonlinear discretizations being primal.  Next in our tour of basic foundational theorems is Godunov’s theorem, which tells us a lot about what is needed. In its original form it’s a bit of a downer, you can’t have a linear method be higher than first-order accurate and non-oscillatory (monotonicity preserving). The key concept is to turn the barrier on its head, you can have a nonlinear method be higher than first-order accurate and non-oscillatory. This is then the instigation for the topic of this post, the need and power of nonlinear methods. I’ll posit the idea that the concept may actually go beyond hyperbolic equations, but the whole concept of nonlinear discretizations is primarily applied to hyperbolic equations.

Next in our tour of basic foundational theorems is Godunov’s theorem, which tells us a lot about what is needed. In its original form it’s a bit of a downer, you can’t have a linear method be higher than first-order accurate and non-oscillatory (monotonicity preserving). The key concept is to turn the barrier on its head, you can have a nonlinear method be higher than first-order accurate and non-oscillatory. This is then the instigation for the topic of this post, the need and power of nonlinear methods. I’ll posit the idea that the concept may actually go beyond hyperbolic equations, but the whole concept of nonlinear discretizations is primarily applied to hyperbolic equations. A few more theorems help to flesh out the basic principles we bring to bear. A key result is the theorem of Lax and Wendroff that shows the value of discrete conservation. If one has conservation then you can show that you are achieving weak solutions. This must be combined with picking the right weak solution, as there are actually infinitely many weak solutions, all of them wrong save one. The task of getting the right weak solution is produced with sufficient dissipation, which produces entropy. Key results are due to Osher who attached the character of (approximate) Riemann solvers to the production of sufficient dissipation to insure physically relevant solutions. As we will describe there are other means to introducing dissipation aside from Riemann solvers, but these lack some degree of theoretical support unless we can tie them directly to the Riemann problem. Of course most of us want physically relevant solutions although lots of mathematicians act like this is not a primal concern! There is a vast phalanx of other

A few more theorems help to flesh out the basic principles we bring to bear. A key result is the theorem of Lax and Wendroff that shows the value of discrete conservation. If one has conservation then you can show that you are achieving weak solutions. This must be combined with picking the right weak solution, as there are actually infinitely many weak solutions, all of them wrong save one. The task of getting the right weak solution is produced with sufficient dissipation, which produces entropy. Key results are due to Osher who attached the character of (approximate) Riemann solvers to the production of sufficient dissipation to insure physically relevant solutions. As we will describe there are other means to introducing dissipation aside from Riemann solvers, but these lack some degree of theoretical support unless we can tie them directly to the Riemann problem. Of course most of us want physically relevant solutions although lots of mathematicians act like this is not a primal concern! There is a vast phalanx of other

theorems of practical interest, but I will end this survey with a last one by Osher and Majda with lots of practical import. Simply stated this theorem limits the numerical accuracy we can achieve in regions affected by a discontinuous solution to first-order accuracy. The impacted region is bounded by the characteristics emanating from the discontinuity. This puts a damper on the zeal for formally high order accurate methods, which needs to be considered in the context of this theorem.

theorems of practical interest, but I will end this survey with a last one by Osher and Majda with lots of practical import. Simply stated this theorem limits the numerical accuracy we can achieve in regions affected by a discontinuous solution to first-order accuracy. The impacted region is bounded by the characteristics emanating from the discontinuity. This puts a damper on the zeal for formally high order accurate methods, which needs to be considered in the context of this theorem. Let’s return to the idea of limiters and act to dissuade the common view of limiters and their intrinsic connection to dissipation. The connection there is real, but less direct than commonly acknowledged. A limiter is really a means of stencil selection in an adaptive manner separate from dissipation. They may be combined, but usually not with good comprehension of the consequences. Another way to view the limiter is a way of selecting the appropriate bias in the stencil used to difference an equation based upon the application of a principle. The principle most often used for limiting is some sort of boundedness in the representation, which may equivalently be associated with selecting a smoother (nicer) neighborhood to execute the discretization on. The way an equation is differenced certainly impacts the nature and need for dissipation in the solution, but it is indirect. Put differently, the amount of dissipation needed with the application of a limiter varies both with the limiter itself, but also with the dissipation mechanism, but the two are independent. This does get into the whole difference between flux limiters and geometric limiters, a topic worth some digestion.

Let’s return to the idea of limiters and act to dissuade the common view of limiters and their intrinsic connection to dissipation. The connection there is real, but less direct than commonly acknowledged. A limiter is really a means of stencil selection in an adaptive manner separate from dissipation. They may be combined, but usually not with good comprehension of the consequences. Another way to view the limiter is a way of selecting the appropriate bias in the stencil used to difference an equation based upon the application of a principle. The principle most often used for limiting is some sort of boundedness in the representation, which may equivalently be associated with selecting a smoother (nicer) neighborhood to execute the discretization on. The way an equation is differenced certainly impacts the nature and need for dissipation in the solution, but it is indirect. Put differently, the amount of dissipation needed with the application of a limiter varies both with the limiter itself, but also with the dissipation mechanism, but the two are independent. This does get into the whole difference between flux limiters and geometric limiters, a topic worth some digestion. approach separates these effects into independent steps. The geometric approach puts bounds on the variables being solved, and then relies on an agnostic approach to the variables for stabilization in the form of a Riemann solver. Both approaches are successful in solving complex systems of equations and have their rabid adherents (I favor the reconstruct-Riemann approach). The flux form can be quite effective and produces better extensions to multiple dimensions, but can also involve heavy-handed dissipation mechanisms.

approach separates these effects into independent steps. The geometric approach puts bounds on the variables being solved, and then relies on an agnostic approach to the variables for stabilization in the form of a Riemann solver. Both approaches are successful in solving complex systems of equations and have their rabid adherents (I favor the reconstruct-Riemann approach). The flux form can be quite effective and produces better extensions to multiple dimensions, but can also involve heavy-handed dissipation mechanisms. The first stabilization of numerical methods was found with the original artificial viscosity (developed by Robert Richtmyer to stabilize and make useful John Von Neumann’s numerical method for shock waves). The name “artificial viscosity” is vastly unfortunate because the dissipation is utterly physical. Without its presence the basic numerical method was utterly and completely useless leading to a catastrophic instability (almost certainly helped instigate the investigation of numerical stability along with instability in integrating parabolic equations). Physically most interesting nonlinear systems produce dissipation even in the limit where the explicit dissipation can be regarded as vanishingly small. This is true for shock waves and turbulence where the dissipation in the inviscid limit has

The first stabilization of numerical methods was found with the original artificial viscosity (developed by Robert Richtmyer to stabilize and make useful John Von Neumann’s numerical method for shock waves). The name “artificial viscosity” is vastly unfortunate because the dissipation is utterly physical. Without its presence the basic numerical method was utterly and completely useless leading to a catastrophic instability (almost certainly helped instigate the investigation of numerical stability along with instability in integrating parabolic equations). Physically most interesting nonlinear systems produce dissipation even in the limit where the explicit dissipation can be regarded as vanishingly small. This is true for shock waves and turbulence where the dissipation in the inviscid limit has remarkably similar forms structurally. Given this basic need, the application of some sort of stabilization is an absolute necessity to produce meaningful results both from a purely numerical respect and the implicit connection to the physical World. I’ve written recently on the use of hyperviscosity as yet another mechanism for producing dissipation. Here the artificial viscosity is the archetype of hyperviscosity and its simplest form. As I’ve mentioned before the original turbulent subgrid model was also based directly upon the artificial viscosity devised by Richtmyer (often misattributed to Von Neumann although their collaboration clearly was important).

remarkably similar forms structurally. Given this basic need, the application of some sort of stabilization is an absolute necessity to produce meaningful results both from a purely numerical respect and the implicit connection to the physical World. I’ve written recently on the use of hyperviscosity as yet another mechanism for producing dissipation. Here the artificial viscosity is the archetype of hyperviscosity and its simplest form. As I’ve mentioned before the original turbulent subgrid model was also based directly upon the artificial viscosity devised by Richtmyer (often misattributed to Von Neumann although their collaboration clearly was important). mind and a two way street.

mind and a two way street.