Taking a new step, uttering a new word, is what people fear most.

― Fyodor Dostoyevsky

The title is a bit misleading so it could be concise. A more precise one would be “Progress is mostly incremental; then progress can be (often serendipitously) massive” Without accepting incremental progress as the usual, typical outcome, the massive leap forward is impossible. If incremental progress is not sought as the natural outcome of working with excellence, progress dies completely. The gist of my argument is that attitude and orientation is the key to making things better. Innovation and improvement are the result of having the right attitude and orientation rather than having a plan for it. You cannot schedule breakthroughs, but you can create an environment and work with an attitude that makes it possible, if not likely. The maddening thing about breakthroughs is their seemingly random nature, you cannot plan for them they just happen, and most of the time they don’t.

The title is a bit misleading so it could be concise. A more precise one would be “Progress is mostly incremental; then progress can be (often serendipitously) massive” Without accepting incremental progress as the usual, typical outcome, the massive leap forward is impossible. If incremental progress is not sought as the natural outcome of working with excellence, progress dies completely. The gist of my argument is that attitude and orientation is the key to making things better. Innovation and improvement are the result of having the right attitude and orientation rather than having a plan for it. You cannot schedule breakthroughs, but you can create an environment and work with an attitude that makes it possible, if not likely. The maddening thing about breakthroughs is their seemingly random nature, you cannot plan for them they just happen, and most of the time they don’t.

For me, the most important aspect of the work environment is the orientation toward excellence and progress. Is work focused on being “the best” or the best we can be? Are we trying to produce “state of the art” results, or are we trying to push the state of the art further? What is the attitude and approach to critique and peer review? What is the attitude toward learning, and adaptively seeking new connections between ideas? How open is the work to accepting, even embracing, serendipitous results? Is the work oriented toward building deep sustainable careers where “world class” expertise is a goal and resources are extended to achieve this end?

Increasingly when I honestly confront all these questions, the answers are troubling. There seems to be the attitude that all of this can be managed, but control of progress is largely an illusion. Usually the answers are significantly oriented away from those that would signify these values. Too often the answers are close to the complete opposite of the “right” ones. What we see is a broad aegis of accountability used to bludgeon the children of progress to death in their proverbial cribs. If accountability isn’t enough to kill progress, compliance is wheeled out as progress’ murder weapon. Used in combination we see advances slow to a crawl, and expertise fail to form where talent and potential was vast. The tragedy of our current system is lost futures first among human’s whose potential greatness is squandered, and secondly in the progress and immense knowledge they would have created. Ultimately all of this damage is heaped upon the future in the name of safety and security that feeds upon pervasive and malignant fear. We are too afraid as a culture to allow people the freedoms needed to be great and do great things.

So much of  modern management seems to think that innovation is something to be managed for and everything can be planned. Like most things where you just try too damn hard, this management approach has exactly the opposite effect. We are actually unintentionally, but actively destroying the environment that allows progress, innovation and breakthroughs to happen. The fastidious planning does the same thing. It is a different thing than having a broad goal and charter that pushes toward a better tomorrow. Today we are expected to plan our research like we are building a goddamn bridge! It is not even remotely the same! The result is the opposite and we are getting less for every research dollar than ever before.

modern management seems to think that innovation is something to be managed for and everything can be planned. Like most things where you just try too damn hard, this management approach has exactly the opposite effect. We are actually unintentionally, but actively destroying the environment that allows progress, innovation and breakthroughs to happen. The fastidious planning does the same thing. It is a different thing than having a broad goal and charter that pushes toward a better tomorrow. Today we are expected to plan our research like we are building a goddamn bridge! It is not even remotely the same! The result is the opposite and we are getting less for every research dollar than ever before.

Without deviation from the norm, progress is not possible.

― Frank Zappa

In a lot of respects getting to an improved state is really quite simple. Two simple changes in how we plan and how we view success at work can make an enormous difference. First we need to always strive to improve, get better whether we are talking personally or in terms of our work. Secondly, we need to not simply be “state of the art” or “world class,” we need to advanced the state of the art, or define what it means to be world class. The driving aim is to strive to be the best and make things better as our default setting. The power of default setting is incredible. The default is so often the unconscious choice that setting the default may be the single most important decision commonly made. As soon as we accept that we, or our work are “good enough” and “fit to purpose” we have lost the battle for the future. The frequency of the default setting of “good enough” is sufficient to ensure that mediocrity creeps inevitably into the frame.

A goal ensures progress. But one gets much further without a goal.

― Marty Rubin

A large part of the problem with our environment is an obsession with measuring performance by the achievement of goals or milestones. Instead of working to create a super productive and empowering work place where people work exceptionally by intrinsic motivation, we simply set “lofty” goals and measure their achievement. The issue is the mindset implicit in the goal setting and measuring; this is the lack of trust in those doing the work. Instead of creating an environment and work processes that enable the best performance, we define everything in terms of milestones. These milestones and the attitudes that surround them sew the seeds of destruction, not because goals are wrong or bad, but because the behavior driven by achieving management goals is so corrosively destructive.

A large part of the problem with our environment is an obsession with measuring performance by the achievement of goals or milestones. Instead of working to create a super productive and empowering work place where people work exceptionally by intrinsic motivation, we simply set “lofty” goals and measure their achievement. The issue is the mindset implicit in the goal setting and measuring; this is the lack of trust in those doing the work. Instead of creating an environment and work processes that enable the best performance, we define everything in terms of milestones. These milestones and the attitudes that surround them sew the seeds of destruction, not because goals are wrong or bad, but because the behavior driven by achieving management goals is so corrosively destructive.

The result is loss of an environment that can enable the best results as a focus, and goal setting that becomes increasingly risk adverse. When goals and milestones are used to judge people, they start to set the bar lower to make sure they meet the standard. The better approach is to create the environment, culture and processes that enable the work to be the best, and reap the rewards that flow naturally. Moreover in the process of creating the environment, culture and process the workplace is happier, as well as higher performing. Intrinsic motivation is harnessed instead of crushed. Everyone benefits from a better workplace and better performance, but we lack the trust needed to do this. Setting goals and milestones simply over charges the achievement and leaves little or no room for the risk necessary for innovation. We find ourselves in a system where the innovation is killed by the lack of risk taking that milestone driven management creates.

So how does progress really work? The truth is that there are really very few major breakthroughs, and almost none of them are every planned. Most of the time people simply make incremental changes and improvements, which have small, but positive changes on what they work on. These are bricks in the wall and gentle nudges to the status quo. Occasionally these small positive changes cause something greater. Occasionally the little thing becomes something monumental and creates a massive improvement. The trick is that you typically can’t tell what little change will have the big impact in advance. Without looking for the small changes as a way of life, and a constant property, the next big thing never comes.

This is the trap of planning. You can’t plan breakthroughs and can’t schedule a better future. Getting to massive improvements is more about creating an environment of excellence, and continuous improvement than any sort of change agenda. The key to getting breakthroughs is to get really good people to work on improving the state of the art or state of the knowledge continuously. We need broad and expansive goals with aspirational character. Instead we have overly specific goals that simply ooze a deep distrust for those conducting the work. With the lack of trust and faith in how the work is done people retract to promising the sure thing, or simply the thing they have already accomplished. The death of progress is found by having a culture of simply implementing and staying at the state of the art or being world class.

The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.

― George Bernard Shaw

Lots of examples exist in the technical world whether it is new numerical methods, or technology (like GPS for example). Almost none of these sought to change the World, but they did by simply taking a key step over a threshold where the change became great. Social movements are another prime example.

. Take the fight for marriage equality as a great example of the small things leading to huge changes. A county clerk in New Mexico (Dona Ana where Las Cruces is located) stood up and granted marriage licenses to gay and lesbian citizens. This step along with other small actions across the country launched a tidal wave of change that culminated in making marriage equality the law for the entire nation.

So the difference is really simple and clear. You must be expanding the state of the art, or defining what it means to be world class. Simply being at the state of the art or world class is not enough. Progress depends on being committed and working actively at improving upon and defining state of the art and world-class work. Little improvements can lead to the massive breakthroughs everyone aspires toward, and really are the only way to get them. Generally all these things are serendipitous and depend entirely on a culture that creates positive change and prizes excellence. One never really knows where the tipping point is and getting to the breakthrough depends mostly on the faith that it is out there waiting to be discovered.

So the difference is really simple and clear. You must be expanding the state of the art, or defining what it means to be world class. Simply being at the state of the art or world class is not enough. Progress depends on being committed and working actively at improving upon and defining state of the art and world-class work. Little improvements can lead to the massive breakthroughs everyone aspires toward, and really are the only way to get them. Generally all these things are serendipitous and depend entirely on a culture that creates positive change and prizes excellence. One never really knows where the tipping point is and getting to the breakthrough depends mostly on the faith that it is out there waiting to be discovered.

Be the change that you wish to see in the world.

― Mahatma Gandhi

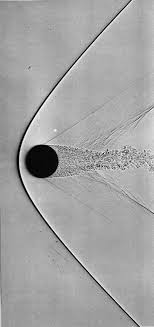

Computing the solution to flows containing shock waves used to be exceedingly difficult, and for a lot of reasons it is now modestly difficult. Solutions for many problems may now be considered routine, but numerous pathologies exist and the limit of what is possible still means research progress are vital. Unfortunately there seems to be little interest in making such progress from those funding research, it goes in the pile of solved problems. Worse yet, there a numerous preconceptions about results, and standard practices about how results are presented that contend to inhibit progress. Here, I will outline places where progress is needed and how people discuss research results in a way that furthers the inhibitions.

Computing the solution to flows containing shock waves used to be exceedingly difficult, and for a lot of reasons it is now modestly difficult. Solutions for many problems may now be considered routine, but numerous pathologies exist and the limit of what is possible still means research progress are vital. Unfortunately there seems to be little interest in making such progress from those funding research, it goes in the pile of solved problems. Worse yet, there a numerous preconceptions about results, and standard practices about how results are presented that contend to inhibit progress. Here, I will outline places where progress is needed and how people discuss research results in a way that furthers the inhibitions. table. To do the best job means making some hard choices that often fly in the face of ideal circumstances. By making these hard choices you can produce far better methods for practical use. It often means sacrificing things that might be nice in an ideal linear world for the brutal reality of a nonlinear world. I would rather have something powerful and functional in reality than something of purely theoretical interest. The published literature seems to be opposed to this point-of-view with a focus on many issues of little practical importance.

table. To do the best job means making some hard choices that often fly in the face of ideal circumstances. By making these hard choices you can produce far better methods for practical use. It often means sacrificing things that might be nice in an ideal linear world for the brutal reality of a nonlinear world. I would rather have something powerful and functional in reality than something of purely theoretical interest. The published literature seems to be opposed to this point-of-view with a focus on many issues of little practical importance. upon this example. Worse yet, the difficulty of extending Lax’s work is monumental. Moving into high dimensions invariably leads to instability and flow that begins to become turbulent, and turbulence is poorly understood. Unfortunately we are a long way from recreating Lax’s legacy in other fields (see e.g.,

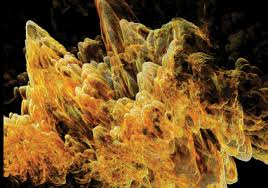

upon this example. Worse yet, the difficulty of extending Lax’s work is monumental. Moving into high dimensions invariably leads to instability and flow that begins to become turbulent, and turbulence is poorly understood. Unfortunately we are a long way from recreating Lax’s legacy in other fields (see e.g.,  where it does not. Progress in turbulence is stagnant and clearly lacks key conceptual advances necessary to chart a more productive path. It is vital to do far more than simply turn codes loose on turbulent problems and let great solutions come out because they won’t. Nonetheless, it is the path we are on. When you add shocks and compressibility to the mix, everything gets so much worse. Even the most benign turbulence is poorly understood much less anything complicated. It is high time to inject some new ideas into the study rather than continue to hammer away at the failed old ones. In closing this vignette, I’ll offer up a different idea: perhaps the essence of turbulence is compressible and associated with shocks rather than being largely divorced from these physics. Instead of building on the basis of the decisively unphysical aspects of incompressibility, turbulence might be better built upon a physical foundation of compressible (thermodynamic) flows with dissipative discontinuities (shocks) that fundamental observations call for and current theories cannot explain.

where it does not. Progress in turbulence is stagnant and clearly lacks key conceptual advances necessary to chart a more productive path. It is vital to do far more than simply turn codes loose on turbulent problems and let great solutions come out because they won’t. Nonetheless, it is the path we are on. When you add shocks and compressibility to the mix, everything gets so much worse. Even the most benign turbulence is poorly understood much less anything complicated. It is high time to inject some new ideas into the study rather than continue to hammer away at the failed old ones. In closing this vignette, I’ll offer up a different idea: perhaps the essence of turbulence is compressible and associated with shocks rather than being largely divorced from these physics. Instead of building on the basis of the decisively unphysical aspects of incompressibility, turbulence might be better built upon a physical foundation of compressible (thermodynamic) flows with dissipative discontinuities (shocks) that fundamental observations call for and current theories cannot explain. Let’s get to one of the biggest issues that confounds the computation of shocked flows, accuracy, convergence and order-of-accuracy. For computing shock waves, the order of accuracy is limited to first-order for everything emanating from any discontinuity (Majda & Osher 1977). Further more nonlinear systems of equations will invariably and inevitably create discontinuities spontaneously (Lax 1973). In spite of these realities the accuracy of solutions with shocks still matters, yet no one ever measures it. The reasons why it matter are far more subtle and refined, and the impact of accuracy is less pervasive in its victory. When a flow is smooth enough to allow high-order convergence, the accuracy of the solution with high-order methods is unambiguously superior. With smooth solutions the highest order method is the most efficient if you are solving for equivalent accuracy. When convergence is limited to first-order the high-order methods effectively lower the constant in front of the error term, which is less efficient. One then has the situation where the gains with high-order must be balanced with the cost of achieving high-order. In very many cases this balance is not achieved.

Let’s get to one of the biggest issues that confounds the computation of shocked flows, accuracy, convergence and order-of-accuracy. For computing shock waves, the order of accuracy is limited to first-order for everything emanating from any discontinuity (Majda & Osher 1977). Further more nonlinear systems of equations will invariably and inevitably create discontinuities spontaneously (Lax 1973). In spite of these realities the accuracy of solutions with shocks still matters, yet no one ever measures it. The reasons why it matter are far more subtle and refined, and the impact of accuracy is less pervasive in its victory. When a flow is smooth enough to allow high-order convergence, the accuracy of the solution with high-order methods is unambiguously superior. With smooth solutions the highest order method is the most efficient if you are solving for equivalent accuracy. When convergence is limited to first-order the high-order methods effectively lower the constant in front of the error term, which is less efficient. One then has the situation where the gains with high-order must be balanced with the cost of achieving high-order. In very many cases this balance is not achieved. se. Everyone knows that the order of accuracy cannot be maintained with a shock or discontinuity, and no one measures the solution accuracy or convergence. The problem is that these details still matter! You need convergent methods, and you have interest in the magnitude of the numerical error. Moreover there are still significant differences in these results on the basis of methodological differences. To up the ante, the methodological differences carry significant changes in the cost of solution. What one finds typically is a great deal of cost to achieve formal order of accuracy that provides very little benefit with shocked flows (see Greenough & Rider 2005, Rider, Greenough & Kamm 2007). This community in the open, or behind closed doors rarely confronts the implications of this reality. The result is a damper on all progress.

se. Everyone knows that the order of accuracy cannot be maintained with a shock or discontinuity, and no one measures the solution accuracy or convergence. The problem is that these details still matter! You need convergent methods, and you have interest in the magnitude of the numerical error. Moreover there are still significant differences in these results on the basis of methodological differences. To up the ante, the methodological differences carry significant changes in the cost of solution. What one finds typically is a great deal of cost to achieve formal order of accuracy that provides very little benefit with shocked flows (see Greenough & Rider 2005, Rider, Greenough & Kamm 2007). This community in the open, or behind closed doors rarely confronts the implications of this reality. The result is a damper on all progress. assessment of error and we ignore its utility perhaps only using it for plotting. What a massive waste! More importantly it masks problems that need attention.

assessment of error and we ignore its utility perhaps only using it for plotting. What a massive waste! More importantly it masks problems that need attention. In the end shocks are a well-trod field with a great deal of theoretical support for a host issues of broader application. If one is solving problems in any sort of real setting, the behavior of solutions is similar. In other words you cannot expect high-order accuracy almost every solution is converging at first-order (at best). By systematically ignoring this issue, we are hurting progress toward better, more effective solutions. What we see over and over again is utility with high-order methods, but only to a degree. Rarely does the fully rigorous achievement of high-order accuracy pay off with better accuracy per unit computational effort. On the other hand methods which are only first-order accurate formally are complete disasters and virtually useless practically. Is the sweet spot second-order accuracy? (Margolin and Rider 2002) Or just second-order accuracy for nonlinear parts of the solution with a limited degree of high-order as applied to the linear aspects of the solution? I think so.

In the end shocks are a well-trod field with a great deal of theoretical support for a host issues of broader application. If one is solving problems in any sort of real setting, the behavior of solutions is similar. In other words you cannot expect high-order accuracy almost every solution is converging at first-order (at best). By systematically ignoring this issue, we are hurting progress toward better, more effective solutions. What we see over and over again is utility with high-order methods, but only to a degree. Rarely does the fully rigorous achievement of high-order accuracy pay off with better accuracy per unit computational effort. On the other hand methods which are only first-order accurate formally are complete disasters and virtually useless practically. Is the sweet spot second-order accuracy? (Margolin and Rider 2002) Or just second-order accuracy for nonlinear parts of the solution with a limited degree of high-order as applied to the linear aspects of the solution? I think so. When one is solving problems involving a flow of some sort, conservation principles are quite attractive since these principles follow nature’s “true” laws (true to the extent we know things are conserved!). With flows involving shocks and discontinuities, the conservation brings even greater benefits as the Lax-Wendroff theorem demonstrates (

When one is solving problems involving a flow of some sort, conservation principles are quite attractive since these principles follow nature’s “true” laws (true to the extent we know things are conserved!). With flows involving shocks and discontinuities, the conservation brings even greater benefits as the Lax-Wendroff theorem demonstrates ( variables don’t). The beauty of primitive variables is that they trivially generalize to multiple dimensions in ways that characteristic variables do not. The other advantages are equally clear specifically the ability to extend the physics of the problem in a natural and simple manner. This sort of extension usually causes the characteristic approach to either collapse or at least become increasingly unwieldy. A key aspect to keep in mind at all times is that one returns to the conservation variables for the final approximation and update of the equations. Keeping the conservation form for the accounting of the complete solution is essential.

variables don’t). The beauty of primitive variables is that they trivially generalize to multiple dimensions in ways that characteristic variables do not. The other advantages are equally clear specifically the ability to extend the physics of the problem in a natural and simple manner. This sort of extension usually causes the characteristic approach to either collapse or at least become increasingly unwieldy. A key aspect to keep in mind at all times is that one returns to the conservation variables for the final approximation and update of the equations. Keeping the conservation form for the accounting of the complete solution is essential. The use of the “primitive variables” came from a number of different directions. Perhaps the earliest use of the term “primitive” came from meteorology in terms of the work of Bjerknes (1921) whose primitive equations formed the basis of early work in computing weather in an effort led by Jules Charney (1955). Another field to use this concept is the solution of incompressible flows. The primitive variables are the velocities and pressure, which is distinguished from the vorticity-streamfunction approach (Roache 1972). In two dimensions the vorticity-streamfunction solution is more efficient, but lacks simple connection to measurable quantities. The same sort of notion separates the conserved variables from the primitive variables in compressible flow. The use of primitive variables as an effective approach computationally may have begun in the computational physics work at Livermore in the 1970’s (see e.g., Debar). The connection of the primitive variables to classical analysis of compressible flows and simple physical interpretation also plays a role.

The use of the “primitive variables” came from a number of different directions. Perhaps the earliest use of the term “primitive” came from meteorology in terms of the work of Bjerknes (1921) whose primitive equations formed the basis of early work in computing weather in an effort led by Jules Charney (1955). Another field to use this concept is the solution of incompressible flows. The primitive variables are the velocities and pressure, which is distinguished from the vorticity-streamfunction approach (Roache 1972). In two dimensions the vorticity-streamfunction solution is more efficient, but lacks simple connection to measurable quantities. The same sort of notion separates the conserved variables from the primitive variables in compressible flow. The use of primitive variables as an effective approach computationally may have begun in the computational physics work at Livermore in the 1970’s (see e.g., Debar). The connection of the primitive variables to classical analysis of compressible flows and simple physical interpretation also plays a role. Now we can elucidate how to move between these two forms, and even use the primitive variables for the analysis of the conserved form directly. Using Huynh’s paper as a guide and repeating the main results one defines a matrix of partial derivatives of the conserved variables,

Now we can elucidate how to move between these two forms, and even use the primitive variables for the analysis of the conserved form directly. Using Huynh’s paper as a guide and repeating the main results one defines a matrix of partial derivatives of the conserved variables,