Magic’s just science that we don’t understand yet.

― Arthur C. Clarke

Scientific discovery and wonder can often be viewed as magic. Some things we can do with our knowledge of the universe can seem magical until you understand them. We commonly use technology that would seem magical to people only a few decades ago. Our ability to discover, innovate and build upon or knowledge creates opportunity for better, happier and longer healthy lives for humanity. In many ways technology is the most human of endeavors and sets us apart from the animal kingdom through its ability to harness, control and shape our World to our benefit. Scientific knowledge and discovery is the foundation of all technology, and from this foundation we can produce magical results. I’m increasingly aware of our tendency to shy away from doing the very work that yields magic.

The world is full of magic things, patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper.

― W.B. Yeats

Today I’ll talk about a couple things: the magical power of models, methods, and algorithms, and what it takes to create the magic.

What do I mean by magic with abstract things like models, methods and algorithms in the first place? As I mentioned these things are all basically ideas and these ideas take shape through mathematics and power through computational simulation. Ultimately the  combination of mathematical structure and computer code the ideas can produce almost magical capabilities in understanding and explaining the World around us allowing us to tame reality in new innovative ways. One little correction is immediately in order; models themselves can be useful without computers. Simple models can be solved via analytical means and these solutions provided classical physics with many breakthroughs in the era before computers. Computers offered the ability expand the scope of these solutions to far more difficult and general models of reality.

combination of mathematical structure and computer code the ideas can produce almost magical capabilities in understanding and explaining the World around us allowing us to tame reality in new innovative ways. One little correction is immediately in order; models themselves can be useful without computers. Simple models can be solved via analytical means and these solutions provided classical physics with many breakthroughs in the era before computers. Computers offered the ability expand the scope of these solutions to far more difficult and general models of reality.

This then takes us to the magic from methods and algorithms, which are similar, but differing in character. The method is the means of taking a model and solving it. The method enables a model to be solved, the nature of that solution, and the basic efficiency of the solution. Ultimately the methods power what is possible to achieve with computers. All our modeling and simulation codes depend upon these methods for their core abilities

This then takes us to the magic from methods and algorithms, which are similar, but differing in character. The method is the means of taking a model and solving it. The method enables a model to be solved, the nature of that solution, and the basic efficiency of the solution. Ultimately the methods power what is possible to achieve with computers. All our modeling and simulation codes depend upon these methods for their core abilities

. Without the innovate methods to solve models, the computers would be far less powerful for science. Many great methods have been devised over the past few decades, and advances with methods open the door to new models or simply greater accuracy, or efficiency in their solution. Some methods are magical in their ability to open new models to solution and with those new perspectives on our reality.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

― Arthur C. Clarke

Despite their centrality and essential nature in scientific computing, emphasis and focus on method creation is waning badly. Research into new or better methods has little priority today and the simple transfer (or porting) of existing methods onto new computers is the preferred choice. The blunt truth is that porting a method onto a new computer will produce progress, but no magic. The magic of methods can be more than simply enabling; the best methods bridge a divide between modeling and methods by containing elements of physical modeling. The key example of this character is shock capturing. Shock capturing magically created the ability to solve discontinuous problems in a general way, and paved the way for many if not most of our general application codes.

The magic isn’t limited to just making solutions possible, the means of making the solution possible also added important physical modeling to the equations. The core methodology used for shock capturing is the addition of subgrid dissipative physics (i.e., artificial viscosity). The foundation of shock capturing led directly to large eddy simulation and the ability to simulate turbulence. Improved shock capturing developed in the 1970’s and 1980’s created implicit large eddy simulation. To many this seemed completely magical; the modeling simply came for free. In reality this magic was predictable. The basic method of shock capturing was the same as the basic subgrid modeling in LES. Finding out that improved shock capturing gives automatic LES modeling is actually quite logical. In essence the connection is due to the model leaving key physics out of the equations. Nature doesn’t allow this to go unpunished.

The magic isn’t limited to just making solutions possible, the means of making the solution possible also added important physical modeling to the equations. The core methodology used for shock capturing is the addition of subgrid dissipative physics (i.e., artificial viscosity). The foundation of shock capturing led directly to large eddy simulation and the ability to simulate turbulence. Improved shock capturing developed in the 1970’s and 1980’s created implicit large eddy simulation. To many this seemed completely magical; the modeling simply came for free. In reality this magic was predictable. The basic method of shock capturing was the same as the basic subgrid modeling in LES. Finding out that improved shock capturing gives automatic LES modeling is actually quite logical. In essence the connection is due to the model leaving key physics out of the equations. Nature doesn’t allow this to go unpunished.

One of the aspects of modern science is that it provides a proverbial two-edged sword by understanding the magic. In the understanding we lose the magic, but open the door for new more miraculous capabilities. For implicit LES we have begun to unveil the secrets of its seemingly magical success. The core of the success is simply the same as original shock capturing, producing viable solutions on finite grids occurs via getting physically relevant solutions, which by definition means a dissipative (vanishing viscosity) solution. The new improved shock capturing methods extended the basic ability to solve problems. If one were cognizant of the connection between LES and shock capturing, the magic of implicit LES should be been foreseen.

The real key is the movement to physical admissible second-order accurate methods. Before the advent of modern shock capturing methods guarantees of physical admissibility were limited to first order accuracy. The first-order accuracy brings with it large numerical errors that look just like physical viscosity, which renders all solutions effectively laminar in character. This intrinsic laminar character disappears with second -order accuracy. The trick is that the classical second-order results are oscillatory and prone to being unphysical. Modern shock capturing methods solve this issue and make solutions realizable. It turns out that the fundamental and leading truncation error in a second-order finite volume method produces the same form of dissipation as many models produce in the limit of vanishing viscosity. In other words, the second order solutions match the asymptotic structure of the solutions to the inviscid equations in a deep manner. This structural matching is the basis of the seemingly magic ability of second-order methods to produce convincingly turbulent calculations.

-order accuracy. The trick is that the classical second-order results are oscillatory and prone to being unphysical. Modern shock capturing methods solve this issue and make solutions realizable. It turns out that the fundamental and leading truncation error in a second-order finite volume method produces the same form of dissipation as many models produce in the limit of vanishing viscosity. In other words, the second order solutions match the asymptotic structure of the solutions to the inviscid equations in a deep manner. This structural matching is the basis of the seemingly magic ability of second-order methods to produce convincingly turbulent calculations.

This magic is the tip of the iceberg, and science is about understanding the magic as a route to even greater wizardry. One of the great tragedies of the modern age is the disconnect between these magical results and what we are allowed to do.

We can also get magical results from algorithms. The algorithms are important mathematical tools that enable methods to work. In some cases algorithmic limitations produce significantly limiting efficiency for numerical methods. One of the clearest areas of algorithmic magic is numerical linear algebra. Breakthroughs in numerical linear algebra have produced immense and enabling capabilities for methods. If the linear algebra is inefficient it can limit the capacity for solving problems. Conversely a breakthrough in linear algebra scaling (like multigrid) can allow solutions with a speed, magnitude and efficiency that seems positively magical in nature.

Numerous algorithms have been developed that endow codes with seemingly magical abilities. A recent breakthrough where magical power is ascribable to is compressed sensing. This methodology has seeded a number of related algorithmic capabilities that defy normal rules. The biggest element of compressed sensing is its appetite for sparsity, and sparsity drives good scaling properties. We see magical ability to recover clear images from noisy signals. The key to all of this capability is the marriage of deep mathematical theory to applied mathematical practice, and algorithmic implementation. We should want as much of this sort of magical capabilities as possible. They do seemingly impossible things providing new unforeseen abilities.

In the republic of mediocrity, genius is dangerous.

― Robert G. Ingersoll

We don’t do much of this these days. Model, method and algorithm advancement is difficult and risky. Unfortunately our modern management programs don’t do difficult things well anymore. We do risky things even less. A risky failure prone research program is likely to not be funded. Our management is incapable of taking risks, and progress in all of these areas is very risky. We must be able to absorb many failures in attempting to achieve breakthroughs. Without accepting and managing through these failures, the breakthroughs will not occur. If the breakthroughs occur massive benefits will arise, but these benefit while doubtless are hard to estimate. We are living in the lunacy of the scheduled breakthrough. Our inability to seek success without the possibility of failure is nothing, but unbridled bullshit and the recipe for systematic failure.

There is always danger for those who are afraid.

― George Bernard Shaw

The truly unfortunate aspect of today’s world is the systematic lack of trust in people, expertise, institutions and facts in general. These trustworthiness crises are getting worse, not better, and may be approaching a critical fracture. The end result of the lack of trust is a lack of effective execution of work because people’s hands are tied. The level of control placed on how work is executed is incompatible with serendipitous breakthro ughs and adaption of complex efforts. Instead we tend to have highly controlled and scripted work lacking any innovation and discovery. In other words the control and lack of trust conspire to remove magic as a potential result. Over the years this leads to a lessening of the wonderful things we can accomplish.

ughs and adaption of complex efforts. Instead we tend to have highly controlled and scripted work lacking any innovation and discovery. In other words the control and lack of trust conspire to remove magic as a potential result. Over the years this leads to a lessening of the wonderful things we can accomplish.

If we expect to continue discovering wonderful things we need to change how we manage our programs. We need to start trusting people, expertise, and institutions again. Trust is a wonderful thing. Trust is an empowering thing. Trust drives greater efficiency and allows people to learn and adapt. If we trust people they will discover serendipitous results. Most discoveries are not completely new ideas. A much more common occurrence is for old mature ideas to combine into entirely new ideas. This is a common source of magical and new capabilities. Currently the controls placed on work driven by lack of trust remove most of the potential for a marriage of new ideas. The new ideas simply never meet and never have a chance to become something new and amazing. We need to give trust and relinquish some control if we want great things to happen.

The problem with releasing control and giving trust is the acceptance of risk. Anything new, wonderful, even magical will also entail great risk of failure. If one desires the magic, one must also accept the possibility of failure. The two things are intrinsically linked and utterly dependent. Without risks the reward will not materialize. The ability to take large risks, highly prone to failure is necessary to expose discoveries. The magic is out there waiting to be uncovered by those with the courage to take the risks.

Being the successful and competent at high performance computing (HPC) is an essential enabling technology for supporting many scientific, military and industrial activities. It plays an important role in national defense, economics, cyber-everything and a measure of National competence. So it is important. Being the top nation in high performance computers is an important benchmark in defining national power. It does not measure overall success or competence, but rather a component of those things. Success and competence in high performance computing depends on a number of things including physics modeling and experimentation, applied mathematics, many types of engineering including software engineering, and computer hardware. In the list of these things computing hardware is among the least important aspects of competence. It is generally enabling for everything else, but hardly defines competence. In other words, hardware is necessary and far from sufficient.

Being the successful and competent at high performance computing (HPC) is an essential enabling technology for supporting many scientific, military and industrial activities. It plays an important role in national defense, economics, cyber-everything and a measure of National competence. So it is important. Being the top nation in high performance computers is an important benchmark in defining national power. It does not measure overall success or competence, but rather a component of those things. Success and competence in high performance computing depends on a number of things including physics modeling and experimentation, applied mathematics, many types of engineering including software engineering, and computer hardware. In the list of these things computing hardware is among the least important aspects of competence. It is generally enabling for everything else, but hardly defines competence. In other words, hardware is necessary and far from sufficient.

kicking the habit is hard. In a sense under Moore’s law computer performance skyrocketed for free, and people are not ready to see it go.

kicking the habit is hard. In a sense under Moore’s law computer performance skyrocketed for free, and people are not ready to see it go. other areas due its difficulty of use. This goes above and beyond the vast resource sink the hardware is.

other areas due its difficulty of use. This goes above and beyond the vast resource sink the hardware is. I work on this program and quietly make all these points. They fall of deaf ears because the people committed to hardware dominate the national and international conversations. Hardware is an easier sell to the political class who are not sophisticated enough to smell the bullshit they are being fed. Hardware has worked to get funding before, so we go back to the well. Hardware advances are easy to understand and sell politically. The more naïve and superficial the argument, the better fit it is for our increasingly elite-unfriendly body politic. All the other things needed for HPC competence and advances are supported largely by pro bono work. They are simply added effort that comes down to doing the right thing. There is a rub that puts all this good faith effort at risk. The balance and all the other work is not a priority or emphasis of the program. Generally it is not important or measured in the success of the program, or defined in the tasking from the funding agencies.

I work on this program and quietly make all these points. They fall of deaf ears because the people committed to hardware dominate the national and international conversations. Hardware is an easier sell to the political class who are not sophisticated enough to smell the bullshit they are being fed. Hardware has worked to get funding before, so we go back to the well. Hardware advances are easy to understand and sell politically. The more naïve and superficial the argument, the better fit it is for our increasingly elite-unfriendly body politic. All the other things needed for HPC competence and advances are supported largely by pro bono work. They are simply added effort that comes down to doing the right thing. There is a rub that puts all this good faith effort at risk. The balance and all the other work is not a priority or emphasis of the program. Generally it is not important or measured in the success of the program, or defined in the tasking from the funding agencies. We live in an era where we are driven to be unwaveringly compliant to rules and regulations. In other words you work on what you’re paid to work on, and you’re paid to complete the tasks spelled out in the work orders. As a result all of the things you do out of good faith and responsibility can be viewed as violating these rules. Success might depend doing all of these unfunded and unstated things, but the defined success from the work contracts are missing these elements. As a result the things that need to be done; do not get done. More often than not, you receive little credit or personal success from pursing doing the right thing. You do not get management or institutional support either. Expecting these unprioritized, unintentional things to happen is simply magical thinking.

We live in an era where we are driven to be unwaveringly compliant to rules and regulations. In other words you work on what you’re paid to work on, and you’re paid to complete the tasks spelled out in the work orders. As a result all of the things you do out of good faith and responsibility can be viewed as violating these rules. Success might depend doing all of these unfunded and unstated things, but the defined success from the work contracts are missing these elements. As a result the things that need to be done; do not get done. More often than not, you receive little credit or personal success from pursing doing the right thing. You do not get management or institutional support either. Expecting these unprioritized, unintentional things to happen is simply magical thinking. We have the situation where the priorities of the program are arrayed toward success in a single area that puts other areas needed for success at risk. Management then asks people to do good faith pro bono work to make up the difference. This good faith work violates the letter of the law in compliance toward contracted work. There appears to be no intention of supporting all of the other disciplines needed for success. We rely upon people’s sense of responsibility for closing this gap even when we drive a sense of duty that pushes against doing any extra work. In addition, the hardware focus levies an immense tax on all other work because the hardware is so incredibly user-unfriendly. The bottom line is a systematic abdication of responsibility by those charged with leading our efforts. Moreover we exist within a time and system where grass roots dissent and negative feedback is squashed. Our tepid and incompetent leadership can rest assured that their decisions will not be questioned.

We have the situation where the priorities of the program are arrayed toward success in a single area that puts other areas needed for success at risk. Management then asks people to do good faith pro bono work to make up the difference. This good faith work violates the letter of the law in compliance toward contracted work. There appears to be no intention of supporting all of the other disciplines needed for success. We rely upon people’s sense of responsibility for closing this gap even when we drive a sense of duty that pushes against doing any extra work. In addition, the hardware focus levies an immense tax on all other work because the hardware is so incredibly user-unfriendly. The bottom line is a systematic abdication of responsibility by those charged with leading our efforts. Moreover we exist within a time and system where grass roots dissent and negative feedback is squashed. Our tepid and incompetent leadership can rest assured that their decisions will not be questioned. Before getting to my conclusion, one might reasonably ask, “what should we be doing instead?” First we need an HPC program with balance between the impact on reality and the stream of enabling technology. The single most contemptible aspect of current programs is the nature of the hardware focus. The computers we are building are monstrosities, largely unfit for scientific use and vomitously inefficient. They are chasing a meaningless summit of performance measured through an antiquated and empty benchmark. We would be better served through building computers tailored to scientific computation that solve real important problems with efficiency. We should be building computers and software that spur our productivity and are easy to

Before getting to my conclusion, one might reasonably ask, “what should we be doing instead?” First we need an HPC program with balance between the impact on reality and the stream of enabling technology. The single most contemptible aspect of current programs is the nature of the hardware focus. The computers we are building are monstrosities, largely unfit for scientific use and vomitously inefficient. They are chasing a meaningless summit of performance measured through an antiquated and empty benchmark. We would be better served through building computers tailored to scientific computation that solve real important problems with efficiency. We should be building computers and software that spur our productivity and are easy to use. Instead we levy an enormous penalty toward any useful application of these machines because of their monstrous nature. A refocus away from the meaningless summit defined by an outdated benchmark could have vast benefits for science.

use. Instead we levy an enormous penalty toward any useful application of these machines because of their monstrous nature. A refocus away from the meaningless summit defined by an outdated benchmark could have vast benefits for science.

money. If something is not being paid for it is not important. If one couples steadfast compliance with only working on what you’re funded to do, any call to do the right thing despite funding is simply comical. The right thing becomes complying, and the important thing in this environment is funding the right things. As we work to account for every dime of spending in ever finer increments, the importance of sensible and visionary leadership becomes greater. The very nature of this accounting tsunami is to blunt and deny visionary leadership’s ability to exist. The end result is spending every dime as intended and wasting the vast majority of it on shitty, useless results. Any other outcome in the modern world is implausible.

money. If something is not being paid for it is not important. If one couples steadfast compliance with only working on what you’re funded to do, any call to do the right thing despite funding is simply comical. The right thing becomes complying, and the important thing in this environment is funding the right things. As we work to account for every dime of spending in ever finer increments, the importance of sensible and visionary leadership becomes greater. The very nature of this accounting tsunami is to blunt and deny visionary leadership’s ability to exist. The end result is spending every dime as intended and wasting the vast majority of it on shitty, useless results. Any other outcome in the modern world is implausible. Despite a relatively obvious path to fulfillment, the estimation of numerical error in modeling and simulation appears to be worryingly difficult to achieve. A big part of the problem is outright laziness, inattention, and poor standards. A secondary issue is the mismatch between theory and practice. If we maintain reasonable pressure on the modeling and simulation community we can overcome the first problem, but it does require not accepting substandard work. The second problem requires some focused research, along with a more pragmatic approach to practical problems. Along with these systemic issues we can deal with a simpler problem, where to put the error bars on simulations, or should they show a bias or symmetric error. I strongly favor a bias.

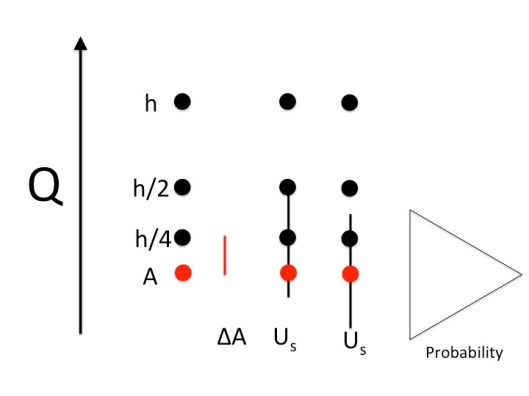

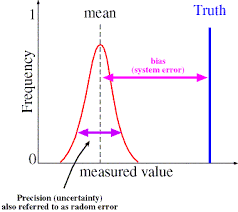

Despite a relatively obvious path to fulfillment, the estimation of numerical error in modeling and simulation appears to be worryingly difficult to achieve. A big part of the problem is outright laziness, inattention, and poor standards. A secondary issue is the mismatch between theory and practice. If we maintain reasonable pressure on the modeling and simulation community we can overcome the first problem, but it does require not accepting substandard work. The second problem requires some focused research, along with a more pragmatic approach to practical problems. Along with these systemic issues we can deal with a simpler problem, where to put the error bars on simulations, or should they show a bias or symmetric error. I strongly favor a bias. The core issue I’m talking about is the position of the numerical error bar. Current approaches center the error bar on the finite grid solution of interest, usually the finest mesh used. This has the effect of giving the impression that this solution is the most likely answer, and the true answer could be either direction from that answer. Neither of these suggestions is supported by the data used to construct the error bar. For this reason the standard practice today is problematic and should be changed to something supportable by the evidence. The current error bars suggest incorrectly that the most likely error is zero. This is completely and utterly unsupported by evidence.

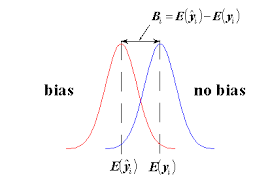

The core issue I’m talking about is the position of the numerical error bar. Current approaches center the error bar on the finite grid solution of interest, usually the finest mesh used. This has the effect of giving the impression that this solution is the most likely answer, and the true answer could be either direction from that answer. Neither of these suggestions is supported by the data used to construct the error bar. For this reason the standard practice today is problematic and should be changed to something supportable by the evidence. The current error bars suggest incorrectly that the most likely error is zero. This is completely and utterly unsupported by evidence. mulation examples in existence are subject to bias in the solutions. This bias comes from numerical solution, modeling inadequacy, and bad assumptions to name a few of the sources. In contrast uncertainty quantification is usually applied in a statistical and clearly unbiased manner. This is a serious difference in perspective. The differences are clear. With bias the difference between simulation and reality is one sided and the deviation can be cured by calibrating parts of the model to compensate. Unbiased uncertainty is common in measurement error and ends up dominating the approach to UQ in simulations. The result is a mismatch between the dominant mode of uncertainty and how it is modeled. Coming up with a more nuanced and appropriate model that acknowledges and deals with bias appropriately would be great progress.

mulation examples in existence are subject to bias in the solutions. This bias comes from numerical solution, modeling inadequacy, and bad assumptions to name a few of the sources. In contrast uncertainty quantification is usually applied in a statistical and clearly unbiased manner. This is a serious difference in perspective. The differences are clear. With bias the difference between simulation and reality is one sided and the deviation can be cured by calibrating parts of the model to compensate. Unbiased uncertainty is common in measurement error and ends up dominating the approach to UQ in simulations. The result is a mismatch between the dominant mode of uncertainty and how it is modeled. Coming up with a more nuanced and appropriate model that acknowledges and deals with bias appropriately would be great progress. ociated with lack of computational resolution. The computational mesh is always far too coarse for comfort, and the numerical errors are significant. There are also issues associated with initial conditions, energy balance and representing physics at and below the level of the grid. In both cases the models are invariably calibrated heavily. This calibration compensates for the lack of mesh resolution, lack of knowledge of initial data and physics as well as problems with representing the energy balance essential to the simulation (especially climate). A serious modeling deficiency is the merging of all of these uncertainties into the calibration with an associated loss of information.

ociated with lack of computational resolution. The computational mesh is always far too coarse for comfort, and the numerical errors are significant. There are also issues associated with initial conditions, energy balance and representing physics at and below the level of the grid. In both cases the models are invariably calibrated heavily. This calibration compensates for the lack of mesh resolution, lack of knowledge of initial data and physics as well as problems with representing the energy balance essential to the simulation (especially climate). A serious modeling deficiency is the merging of all of these uncertainties into the calibration with an associated loss of information. The issues with calibration are profound. Without calibration the models are effectively useless. For these models to contribute to our societal knowledge and decision-making or raw scientific investigation, the calibration is an absolute necessity. Calibration depends entirely on existing data, and this carries a burden of applicability. How valid is the calibration when the simulation is probing outside the range of the data used to calibrate? We commonly include the intrinsic numerical bias in the calibration, and most commonly a turbulence or mixing model is adjusted to account for the numerical bias. A colleague familiar with ocean models quipped that if the ocean were as viscous as we modeled it, one could drive to London from New York. It is well known that numerical viscosity stabilizes calculation, and we can use numerical methods to model turbulence (implicit large eddy simulation), but this practice should at the very least make people uncomfortable. We are also left with the difficult matter of how to validate models that have been calibrated.

The issues with calibration are profound. Without calibration the models are effectively useless. For these models to contribute to our societal knowledge and decision-making or raw scientific investigation, the calibration is an absolute necessity. Calibration depends entirely on existing data, and this carries a burden of applicability. How valid is the calibration when the simulation is probing outside the range of the data used to calibrate? We commonly include the intrinsic numerical bias in the calibration, and most commonly a turbulence or mixing model is adjusted to account for the numerical bias. A colleague familiar with ocean models quipped that if the ocean were as viscous as we modeled it, one could drive to London from New York. It is well known that numerical viscosity stabilizes calculation, and we can use numerical methods to model turbulence (implicit large eddy simulation), but this practice should at the very least make people uncomfortable. We are also left with the difficult matter of how to validate models that have been calibrated. some part of the model. This issue plays out in weather and climate modeling where the mesh is part of the model rather than independent aspect of it. It should surprise no one that LES was born from weather-climate modeling (at the time where the distinction didn’t exist). In other words the chosen mesh and the model are intimately linked. If the mesh is modified, the modeling must also be modified (recalibrated) to get the balancing of the solution correct. This tends to happen in simulations where an intimate balance is essential to the phenomena. In these cases there is a system that in one respect or another is in a nearly equilibrium state, and the deviations from this equilibrium are essential. Aspects of the modeling related to the scales of interest including the grid itself impact the equilibrium to a degree that an un-calibrated model is nearly useless.

some part of the model. This issue plays out in weather and climate modeling where the mesh is part of the model rather than independent aspect of it. It should surprise no one that LES was born from weather-climate modeling (at the time where the distinction didn’t exist). In other words the chosen mesh and the model are intimately linked. If the mesh is modified, the modeling must also be modified (recalibrated) to get the balancing of the solution correct. This tends to happen in simulations where an intimate balance is essential to the phenomena. In these cases there is a system that in one respect or another is in a nearly equilibrium state, and the deviations from this equilibrium are essential. Aspects of the modeling related to the scales of interest including the grid itself impact the equilibrium to a degree that an un-calibrated model is nearly useless. h to a value (assuming the rest of the model is held fixed) then the error is well behaved. The sequence of solutions on the meshes can then be used to estimate the solution to the mathematical problem, that is the solution where the mesh resolution is infinite (absurd as it might be). Along with this estimate of the “perfect” solution, the error can be estimated for any of the meshes. For this well-behaved case the error is one sided, a bias between the ideal solution and the one with a mesh. Any fuzz in the estimate would be applied to the bias. In other words any uncertainty in the error estimate is centered about the extrapolated “perfect” solution, not the finite grid solutions. The problem with the current accepted methodology is that the error is given as a standard two-sided error bar that is appropriate for statistical errors. In other words we use a two-sided accounting for this error even though there is no evidence for it. This is a problem that should be corrected. I should note that many models (i.e., like climate or weather) invariably recalibrate after all mesh changes, which invalidates the entire verification exercise where the model aside from the grid should be fixed across the mesh sequence.

h to a value (assuming the rest of the model is held fixed) then the error is well behaved. The sequence of solutions on the meshes can then be used to estimate the solution to the mathematical problem, that is the solution where the mesh resolution is infinite (absurd as it might be). Along with this estimate of the “perfect” solution, the error can be estimated for any of the meshes. For this well-behaved case the error is one sided, a bias between the ideal solution and the one with a mesh. Any fuzz in the estimate would be applied to the bias. In other words any uncertainty in the error estimate is centered about the extrapolated “perfect” solution, not the finite grid solutions. The problem with the current accepted methodology is that the error is given as a standard two-sided error bar that is appropriate for statistical errors. In other words we use a two-sided accounting for this error even though there is no evidence for it. This is a problem that should be corrected. I should note that many models (i.e., like climate or weather) invariably recalibrate after all mesh changes, which invalidates the entire verification exercise where the model aside from the grid should be fixed across the mesh sequence. quantities that cannot be measured. In this case the uncertainty must be approached carefully. The uncertainty in these values must almost invariably be larger than the quantities used for calibration. One needs to look at the modeling connections for these values and attack a reasonable approach to treating the quantities with an appropriate “grain of salt”. This includes numerical error, which I talked about above too. In the best case there is data available that was not used to calibrate the model. Maybe these are values that are not as highly prized or as important as those used to calibrate. The uncertainty between these measured data values and the simulation gives very strong indications regarding the uncertainty in the simulation. In other cases some of the data potentially available for calibration has been left out, and can be used for validating the calibrated model. This assumes that the hold-out data is sufficiently independent of the data used.

quantities that cannot be measured. In this case the uncertainty must be approached carefully. The uncertainty in these values must almost invariably be larger than the quantities used for calibration. One needs to look at the modeling connections for these values and attack a reasonable approach to treating the quantities with an appropriate “grain of salt”. This includes numerical error, which I talked about above too. In the best case there is data available that was not used to calibrate the model. Maybe these are values that are not as highly prized or as important as those used to calibrate. The uncertainty between these measured data values and the simulation gives very strong indications regarding the uncertainty in the simulation. In other cases some of the data potentially available for calibration has been left out, and can be used for validating the calibrated model. This assumes that the hold-out data is sufficiently independent of the data used. certainty is to apply significant variation to the parameters used to calibrate the model. In addition we should include the numerical error in the uncertainty. In the case of deeply calibrated models these sources of uncertainty can be quite large and generally paint an overly pessimistic picture of the uncertainty. Conversely we have an extremely optimistic picture of uncertainty with calibration. The hope and best possible outcome is that these two views bound reality, and the true uncertainty lies between these extremes. For decision-making using simulation this bounding approach to uncertainty quantification should serve us well.

certainty is to apply significant variation to the parameters used to calibrate the model. In addition we should include the numerical error in the uncertainty. In the case of deeply calibrated models these sources of uncertainty can be quite large and generally paint an overly pessimistic picture of the uncertainty. Conversely we have an extremely optimistic picture of uncertainty with calibration. The hope and best possible outcome is that these two views bound reality, and the true uncertainty lies between these extremes. For decision-making using simulation this bounding approach to uncertainty quantification should serve us well.