Rigor alone is paralytic death, but imagination alone is insanity.

― Gregory Bateson

Solving hyperbolic conservation laws provides a rich vein of knowledge to mine and utilize more generally. Most canonically this involves solving the equations of gas dynamics, but the lessons apply to a host of other equations such as magneto-hydrodynamics, multi-material hydrodynamics, oil-water flow, solid mechanics, and on and on. Gas dynamics is commonly visible in the real world, and includes lots of nonlinearity, structure and complexity to contend with. The structures and complexity includes compressible flow structures such as shock waves, rarefactions and contract discontinuities. In more than one dimension you have shear waves, and instabilities that ultimately lead to turbulent flows. With all of these complications to deal with, these flows present numerous challenges to their robust, reliable and accurate simulation. As such, gas dynamics provides a great springboard for robust methods in many fields as well as a proving ground for much of applied math, engineering and physics. It provides a wonderful canvas for the science and art of modeling and simulation to be improved in the vain, but beneficial at tempt at perfection.

tempt at perfection.

Getting a basic working code can come through a variety of ways using some basic methods that provide lots of fundamental functionality. Some of the common options are TVD methods (ala Sweby for example), high order Godunov methods (ala Colella et al), FCT methods (ala Zalesak), or even WENO (Shu and company). For some of these methods the tricks leading to robustness make it into print (Colella, Zalesak come to mind in this regard). All of these will give a passable to even a great solution to most problems, but still all of them can be pushed over the edge with a problem that’s hard enough. So what defines a robust calculation? Let’s say you’ve taken my advice and brutalized your code https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2017/06/09/brutal-problems-make-for-swift-progress/ and now you need to fix your method https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2017/06/16/that-brutal-problem-broke-my-code-what-do-i-do/. This post will provide you with a bunch of ideas about techniques, or recipes to get you across that finish line.

You can’t really know what you are made of until you are tested.

― O.R. Melling

The starting basis for getting a robust code is choosing a good starting point, a strong foundation to work from. Each of the methods above would to a significant degree define this. Opinions differ on which of the available options are best, so I won’t be prescriptive about it (I prefer high-order Godunov methods in the interest of transparency). For typical academic problems, this foundation can be drawn from a wide range of available methods, but these methods often are not up to the job in “real” codes. There are a lot more things to add to a method to get you all the way to a production code. These are more than just bells and whistles; the techniques discussed here can be the difference between success and failure. Usually these tricks of the trade are found through hard fought battles and failures. Each failure offers the opportunity to produce something better and avoid problems. The best recipes produce reliable results for the host of problems you ask the code to solve. A great method won’t fall apart when you ask it to do something new either.

The methods discussed above all share some common things. First and foremost is reliance upon a close to bulletproof first order method as the ground state for the higher order method. This is the first step in building robust methods, start with a first-order method that is very reliable and almost guaranteed to give a physically admissible solution. This is easier said than done for general cases. We know that theoretically the lowest dissipation method with all the necessary characteristics is Godunov’s method (see Osher’s work from the mid-1980’s). At the other end of the useful first-order method spectrum is Lax-Friedrichs method, the most dissipative stable method. In a sense these methods give us our bookends. Any method we use as a foundation will be somewhere between these two. Still coming up with a good foundational first-order method is itself an art. The key is choosing a Riemann solver that provides a reliable solution under even pathological circumstances (in lieu of a Riemann solver, a dissipation that is super reliable).

You cannot build a dream on a foundation of sand. To weather the test of storms, it must be cemented in the heart with uncompromising conviction.

― T.F. Hodge

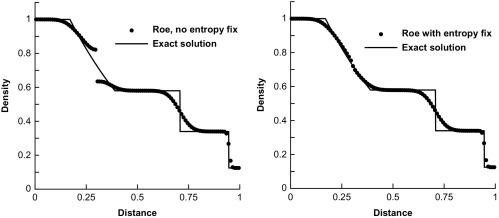

Without further ado let’s get to the techniques that one ought to use. The broadest category of techniques involves adding smart dissipation to methods. This acknowledges that the methods we are using already have a lot of dissipative mechanisms built into them. As a result the added dissipation needs to be selective as hell. The starting point is a careful statement of where the methods already have dissipation. Usually it lies in two distinct places, the most obvious being Riemann solvers or artificial viscosity. The Riemann solver adds an upwind bias to the approximation, which has an implicit dissipative content. The second major source of dissipation is the discretization itself, which can include biases that provide implicit dissipation. For sufficiently complex or nonlinear problems the structural dissipation in the methods are not enough for nonlinear stability. One of the simplest forms for this dissipation is the addition of another dissipative form. For Godunov methods the Lapidus viscosity can be useful because it works at shocks, and adds a multidimensional character. Other viscosity can be added through the Riemann solvers (via so-called entropy fixes, or selecting larger wavespeeds since dissipation is proportional to that). It is important that the dissipation be mechanistically different than the base viscosity, meaning that hyperviscosity (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/03/24/hyperviscosity-is-a-useful-and-important-computational-tool/) can really be useful to augment dissipation. A general principle is to provide multiple alternative routes to nonlinear stability to support each other effectively.

The building blocks that form the foundation of your great and successful future, are the actions you take today

― Topsy Gift

The second source of dissipation is the fundamental discretization, which implicitly provides it. One of the key aspects of modern discretization are limiters that provide nonlinear stability through effectively adapting the discretization to the solution. These limiters come in various forms, but they all provide the means for the method to choose a favorable discretization for the nature of the solution (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/06/22/a-path-to-better-limiters/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/06/14/an-essential-foundation-for-progress/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/06/03/nonlinear-methods-a-key-to-modern-modeling-and-simulation/ ). One of the ways for additional dissipation to enter the method is through a deliberate choice of different limiters. One can bias the adaptive selection of discretization toward more dissipative methods when the solution calls for more care. These choices are important to make when solutions have shock waves, complex nonlinear structures, oscillations, or structural anomalies. For example the minmod limiter based method is the most dissipative second-order, monotonicity-preserving method. It can be used as a less dissipative alternative safety net instead of the first-order methods although its safety is predicated on a bulletproof first order method as a foundation.

Except for all but the most ideal circumstances, the added dissipation is not sufficient to produce a robust method. Very strong nonlinear events that confound classical analysis can still produce problems. All oscillations are very difficult to remove from the solutions and can work to produce distinct threats to the complete stability of the solution. Common ways to deal with these issues in a rather extreme manner are floors and ceilings for various variables. One of the worst things that can happen is a physical quantity moving outside its physically admissible bounds. The simplest example is a density going negative. Density is a positive definite quantity and needs to stay that way for the solution to be physical. It behooves robustness to make sure this does not happen. If it does it is usually catastrophic for the code. This is a simple case and in general quantities should lie within reasonable bounds. Usually when quantities fall outside reasonable bounds the code’s solutions are compromised. It makes sense to explicitly guard against this specifically where a quantity being out of bounds would general a catastrophic effect. For example, sound speeds involve densities and pressure plus a square root operation; a negative value would be disaster.

One can take things a long way toward robustness through using methods that more formally produce bounded approximations. The general case of positivity, or more bounded approximation has been pursued actively. I described the implementation of methods of this sort earlier, (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2015/08/06/a-simple-general-purpose-limiter/ ). These methods can go a very long way to giving the robust character one desires, but other means discussed above are still necessary. A large production code with massive meshes and long run times will access huge swaths of phase space and as the physical complexity of problems increases, almost anything that can happen will. It is foolish to assume that bad states will not occur. One also must contend with people using the code in ways the developers never envisioned, and putting the solver into situations where it must survive even when it was designed for them. As a consequence it would be foolish to completely remove the sorts of checks that avert disaster (this could be done, but only with rigorous testing far beyond what most people ever do).

What to concretely do is another question where there are multiple options. One can institute a floating-point trap that locally avoids the possibility of using a negative value for the square root. This can be done in a variety of ways with differing benefits and pitfalls. One simple approach is to take the square root of the absolute value, or one might choose the max of the density and some sort of small floor value. This does little to address the core reason that the approximations produced an unphysical value. There is also little control on the magnitude of the density (the value can be very small), which has rather unpleasant side effects. A better approach would get closer to the root of the problems, which almost without fail comes from the inappropriate application of high-order approximations. One way for this to be applied is to replace the high-order approximations with a physically admissible low-order approximation. This relies upon the guarantees associated with the low-order (first order) approximation as a general safety net for the computational method. The reality is that the first-order method can also go bad, and the floating-point trap may or certainly be necessary even there.

A basic part of the deterministic solution to many problems is the ability to maintain symmetry. The physical world almost invariably breaks symmetry, but it is arguable that numerical solutions to the PDEs should not (I could provide the alternative argument vigorously too). If you want to maintain such symmetry, the code must be carefully designed to do this. A big source of the symmetry breaking is upwind approximations, especially if one choses a bias where zero isn’t carefully and symmetrically treated. One approach is the use of smoothed operators that I discussed at length (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2017/03/24/smoothed-operators/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2017/03/29/how-useful-are-smoothed-operators/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2017/04/04/results-using-smoothed-operators-in-actual-code/ ). More generally the use of “if” tests in the code will break symmetry. Another key area for symmetry breaking is the solution of linear systems by methods that are not symmetry preserving. This means numerical linear algebra needs to be carefully approached.

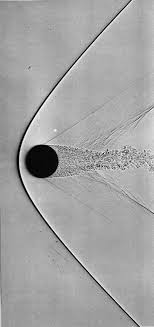

For gas dynamics, the mathematics of the model provide us with some very general character to the problems we solve. Shock waves are the preeminent feature of compressible gas dynamics, and a relatively predominant focal point for methods’ development and developer attention. Shock waves are nonlinear and naturally steepen thus countering dissipative effects. Shocks benefit through their character as garbage collectors, they are dissipative features and as a result destroy information. Some of this destruction limits the damage done by poor choices of numerical treatment. Being nonlinear one has to be careful with shocks. The very worst thing you can do is to add too little dissipation because this will allow the solution to generate unphysical noise or oscillations that are emitted by the shock. These oscillations will then become features of the solution. A lot of the robustness we seek comes from not producing oscillations, which can be best achieved with generous dissipation at shocks. Shocks receive so much attention because their improper treatment is utterly catastrophic, but they are not the only issue; the others are just more subtle and less apparently deadly.

For gas dynamics, the mathematics of the model provide us with some very general character to the problems we solve. Shock waves are the preeminent feature of compressible gas dynamics, and a relatively predominant focal point for methods’ development and developer attention. Shock waves are nonlinear and naturally steepen thus countering dissipative effects. Shocks benefit through their character as garbage collectors, they are dissipative features and as a result destroy information. Some of this destruction limits the damage done by poor choices of numerical treatment. Being nonlinear one has to be careful with shocks. The very worst thing you can do is to add too little dissipation because this will allow the solution to generate unphysical noise or oscillations that are emitted by the shock. These oscillations will then become features of the solution. A lot of the robustness we seek comes from not producing oscillations, which can be best achieved with generous dissipation at shocks. Shocks receive so much attention because their improper treatment is utterly catastrophic, but they are not the only issue; the others are just more subtle and less apparently deadly.

Rarefactions are the benign compatriot to shocks. Rarefactions do not steepen and usually offer modest challenges to computations. Rarefactions produce no dissipation and their spreading nature reduces the magnitude of anything anomalous produced by the simulation. Despite their ease relative to shock waves, the rarefactions do produce some distinct challenges. The simplest case involves centered rarefactions where the characteristic velocity of the rarefaction goes to zero. Since dissipation in methods is proportional to the characteristic velocity, the presence of zero dissipation can trigger disaster and can generate completely unphysical rarefaction shocks (rarefaction shocks can be physical for exotic BZT fluids). More generally for very strong rarefactions one can see small and very worrisome deviations from adhering to the second law, these should be viewed with significant suspicion. The other worrisome feature of most computed rarefactions is the structure of the head of the rarefaction. Usually there is a systematic bump there that is not physical and may produce unphysical solutions for problems featuring very strong expansion waves. This bump actually looks like a shock when viewed through the lens of Lax’s version of the entropy conditions (based on characteristic velocities). This is an unsolved problem at present and represents a challenge to our gas dynamics simulations. The basic issue is that a strong enough rarefaction cannot be solved in an accurate, convergent manner by existing methods.

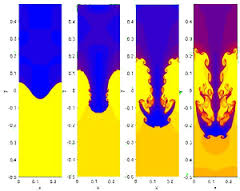

A third outstanding feature of gas dynamics are contact discontinuities, which are classified as linearly degenerate waves. They are quite similar to linear waves meaning that the characteristics do not change across the wave; for the ideal analysis the jumps neither steepen nor spread across the wave. One of the key results is that any numerical error is permanently encoded into the solution. One needs to be careful with dissipation because it never goes away. For this reason people consider steepening the wave to keep it from artificially spreading. It is a bit of an attempt to endow the contact with a little of the character of a shock courting potential catastrophe in the process. This can be dangerous if it is applied to with an interaction with a nonlinear wave, or instability for multidimensional flows. Another feature of the contact is their connection to multi-material interfaces as a material interface can ideally be viewed as a contact. Multi-material flows are a deep well of significant problems and a topic of great depth unto themselves (Abgrall and Karni is an introduction which barely scratches the surface!).

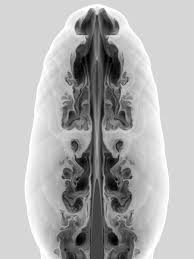

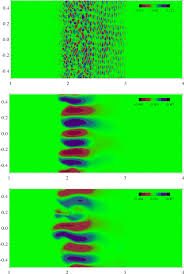

The fourth standard feature is shear waves, which are a different form of linearly degenerate waves. Shear waves are heavily related to turbulence, thus being a huge source of terror. In one dimension shear is rather innocuous being just another contact, but in two or three dimensions our current knowledge and technical capabilities are quickly overwhelmed. Once you have a turbulent flow, one must deal with the conflation of numerical error, and modeling becomes a pernicious aspect of a calculation. In multiple dimensions the shear is almost invariably unstable and solutions become chaotic and boundless in terms of complexity. This boundless complexity means that solutions are significantly mesh dependent, and demonstrably non-convergent in a point wise sense. There may be a convergence in a measure-valued sense, but these concepts are far from well defined, fully explored and technically agreed upon.

The fourth standard feature is shear waves, which are a different form of linearly degenerate waves. Shear waves are heavily related to turbulence, thus being a huge source of terror. In one dimension shear is rather innocuous being just another contact, but in two or three dimensions our current knowledge and technical capabilities are quickly overwhelmed. Once you have a turbulent flow, one must deal with the conflation of numerical error, and modeling becomes a pernicious aspect of a calculation. In multiple dimensions the shear is almost invariably unstable and solutions become chaotic and boundless in terms of complexity. This boundless complexity means that solutions are significantly mesh dependent, and demonstrably non-convergent in a point wise sense. There may be a convergence in a measure-valued sense, but these concepts are far from well defined, fully explored and technically agreed upon.

A couple of general tips for developing a code involves the choice of solution variables. All most without fail, the worst thing you can do is define the approximations using the conserved quantities. This is almost always a more fragile and error prone manner to compute solutions. In general the best approach is to use the so-called primitive variables (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/the-benefits-of-using-primitive-variables/ ). The variables are clear in their physical implications and can be well-bounded using rational means. Using primitive variables is better for almost anything you want to do. The second piece of advice is to use characteristic variables to as great an extent as possible. This always implies some sort of one-dimensional thought. Despite this limitation, the benefits of characteristic variables are so extreme as to justify their use even under these limited circumstances.

A really good general rule is to produce thermodyanically consistent solutions. In other words, don’t mess with thermodynamic consistency, and particularly with the second law of thermodynamics. Parts of this thermodynamic consistency are the dissipative nature of physical solutions and the active adherence to entropy conditions. There are several nuances to this adherence that are worth discussing in more depth. It is generally and commonly known that shocks increase entropy. What isn’t so widely appreciated is the nature of this increase being finite and adheres to a scaling that is proportional to the size of the jump. The dissipation does not converge toward zero, but rather toward a finite value related to the structure of the solution.

The second issue is dissipation free nature of the rest of the flow especially rarefactio ns. The usual aim of solvers is to completely remove dissipation, but that runs the risk of violating the second law. It may be more advisable to keep a small positive dissipation working (perhaps using a hyperviscosity partially because control volumes add a nonlinear anti-dissipative error). This way the code stays away from circumstances that violate this essential physical law. We can work with other forms of entropy satisfaction too. Most notably is Lax’s condition that identifies the structures in a flow by the local behavior of the relevant characteristics of the flow. Across a shock the characteristics flow into the shock, and this condition should be met with dissipation. These structures are commonly present in the head of rarefactions.

ns. The usual aim of solvers is to completely remove dissipation, but that runs the risk of violating the second law. It may be more advisable to keep a small positive dissipation working (perhaps using a hyperviscosity partially because control volumes add a nonlinear anti-dissipative error). This way the code stays away from circumstances that violate this essential physical law. We can work with other forms of entropy satisfaction too. Most notably is Lax’s condition that identifies the structures in a flow by the local behavior of the relevant characteristics of the flow. Across a shock the characteristics flow into the shock, and this condition should be met with dissipation. These structures are commonly present in the head of rarefactions.

One of the big things that can be done to improve solutions is the systematic use of high-order approximations within methods. These high-order elements often involve formal accuracy that is much higher than the overall accuracy of the methods. For example a fourth-order approximation to the first derivative can be used to great effect with a method that only provides an overall second-order accuracy. With methods like PPM and FCT this can be taken to greater extremes. There one might use a fifth or sixth-order approximation for edge values even though the overall method is third order in one dimension or second-order in two or three dimensions. Another aspect of high order accuracy is better accuracy at local extrema. A usual approach to limiting to provide nonlinear stability clips extrema and computes them at first-order accuracy. In moving to limiters that do not clip extrema so harshly, excessive care must be taken so that the resulting method is not fragile and prone to oscillations. Alternatively, extrema-preserving methods can be developed that are relatively dissipative even compared to the better extrema clipping methods. Weighted ENO methods of almost any stripe are examples where the lack of extrema clipping is purchased at the cost of significant dissipation and relatively low overall computational fidelity. A better overall approach would be to use met hods I have devised or the MP methods of Suresh and Huynh. Both of these methods are significantly more accurate than WENO methods.

hods I have devised or the MP methods of Suresh and Huynh. Both of these methods are significantly more accurate than WENO methods.

One of the key points of this work is to make codes robust. Usually these techniques are originally devised as “kludges” that are crude and poorly justified. They have the virtue of working. The overall development effort is to guide these kludges into genuinely defensible methods, and then ultimately to algorithms. One threads the needle between robust solutions and technical rigor that lends confidence and faith in the simulation. The first rule is get an answer, then get a reasonable answer, then get an admissible answer, and then get an accurate answer. The challenges come through the systematic endeavor to solve problems of ever increasing difficulty and expand the capacity of simulations to address an ever-broader scope. We then balance this effort with the availability of knowledge to support the desired rigor. Our standards are arrived at philosophically through what constitutes an acceptable solution to our modeling problems.

Consistency and accuracy instills believability

― Bernard Kelvin Clive

Sweby, Peter K. “High resolution schemes using flux limiters for hyperbolic conservation laws.” SIAM journal on numerical analysis 21, no. 5 (1984): 995-1011.

Jiang, Guang-Shan, and Chi-Wang Shu. “Efficient implementation of weighted ENO schemes.” Journal of computational physics 126, no. 1 (1996): 202-228.

Colella, Phillip, and Paul R. Woodward. “The piecewise parabolic method (PPM) for gas-dynamical simulations.” Journal of computational physics 54, no. 1 (1984): 174-201.

Colella, Phillip. “A direct Eulerian MUSCL scheme for gas dynamics.” SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing 6, no. 1 (1985): 104-117.

Bell, John B., Phillip Colella, and John A. Trangenstein. “Higher order Godunov methods for general systems of hyperbolic conservation laws.” Journal of Computational Physics 82, no. 2 (1989): 362-397.

Zalesak, Steven T. “Fully multidimensional flux-corrected transport algorithms for fluids.” Journal of computational physics 31, no. 3 (1979): 335-362.

Zalesak, Steven T. “The design of Flux-Corrected Transport (FCT) algorithms for structured grids.” In Flux-Corrected Transport, pp. 23-65. Springer Netherlands, 2012.

Quirk, James J. “A contribution to the great Riemann solver debate.” International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 18, no. 6 (1994): 555-574.

Woodward, Paul, and Phillip Colella. “The numerical simulation of two-dimensional fluid flow with strong shocks.” Journal of computational physics 54, no. 1 (1984): 115-173.

| Abgrall, Rémi, and Smadar Karni. “Computations of compressible multifluids.” Journal of computational physics 169, no. 2 (2001): 594-623. |

Osher, Stanley. “Riemann solvers, the entropy condition, and difference.” SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 21, no. 2 (1984): 217-235.

Suresh, A., and H. T. Huynh. “Accurate monotonicity-preserving schemes with Runge–Kutta time stepping.” Journal of Computational Physics 136, no. 1 (1997): 83-99.

Rider, William J., Jeffrey A. Greenough, and James R. Kamm. “Accurate monotonicity-and extrema-preserving methods through adaptive nonlinear hybridizations.” Journal of Computational Physics 225, no. 2 (2007): 1827-1848.

technology and communication unthinkable a generation before. My chosen profession looks increasingly like a relic of that Cold War, and increasingly irrelevant to the World that unfolds before me. My workplace is failing to keep pace with change, and I’m seeing it fall behind modernity in almost every respect. It’s a safe, secure job, but lacks most of the edge the real World offers. All of the forces unleashed in today’s World make for incredible excitement, possibility, incredible terror and discomfort. The potential for humanity is phenomenal, and the risks are profound. In short, we live in simultaneously in incredibly exciting and massively sucky times. Yes, both of these seemingly conflicting things can be true.

technology and communication unthinkable a generation before. My chosen profession looks increasingly like a relic of that Cold War, and increasingly irrelevant to the World that unfolds before me. My workplace is failing to keep pace with change, and I’m seeing it fall behind modernity in almost every respect. It’s a safe, secure job, but lacks most of the edge the real World offers. All of the forces unleashed in today’s World make for incredible excitement, possibility, incredible terror and discomfort. The potential for humanity is phenomenal, and the risks are profound. In short, we live in simultaneously in incredibly exciting and massively sucky times. Yes, both of these seemingly conflicting things can be true. violence increasingly in a state-sponsored way is increasing. The violence against change is growing whether it is by governments or terrorists. What isn’t commonly appreciated is the alliance in violence of the right wing and terrorists. Both are fighting against the sorts of changes modernity is bringing. The fight against terror is giving the violent right wing more power. The right wing and Islamic terrorists have the same aim, undoing the push toward progress with modern views of race, religion and morality. The only difference is the name of the prophet the violence is done in name of.

violence increasingly in a state-sponsored way is increasing. The violence against change is growing whether it is by governments or terrorists. What isn’t commonly appreciated is the alliance in violence of the right wing and terrorists. Both are fighting against the sorts of changes modernity is bringing. The fight against terror is giving the violent right wing more power. The right wing and Islamic terrorists have the same aim, undoing the push toward progress with modern views of race, religion and morality. The only difference is the name of the prophet the violence is done in name of. which provides the rich and powerful the tools to control their societies as well. They also wage war against the sources of terrorism creating the conditions and recruiting for more terrorists. The police states have reduced freedom and lots of censorship, imprisonment, and opposition to personal empowerment. The same police states are effective at repressing minority groups within nations using the weapons gained to fight terror. Together these all help the cause of the right wing in blunting progress. The two allies like to kill each other too, but the forces of hate; fear and doubt work to their greater ends. In fighting terrorism we are giving them exactly what they want, the reduction of our freedom and progress. This is also the aim of right wing; stop the frightening future from arriving through the imposition of traditional values. This is exactly what the religious extremists want be they Islamic or Christian.

which provides the rich and powerful the tools to control their societies as well. They also wage war against the sources of terrorism creating the conditions and recruiting for more terrorists. The police states have reduced freedom and lots of censorship, imprisonment, and opposition to personal empowerment. The same police states are effective at repressing minority groups within nations using the weapons gained to fight terror. Together these all help the cause of the right wing in blunting progress. The two allies like to kill each other too, but the forces of hate; fear and doubt work to their greater ends. In fighting terrorism we are giving them exactly what they want, the reduction of our freedom and progress. This is also the aim of right wing; stop the frightening future from arriving through the imposition of traditional values. This is exactly what the religious extremists want be they Islamic or Christian. Driving the conservatives to such heights of violence and fear are changes to society of massive scale. Demographics are driving the changes with people of color becoming impossible to ignore, along with an aging population. Sexual freedom has emboldened people to break free of traditional boundaries of behavior, gender and relationships. Technology is accelerating the change and empowering people in amazing ways. All of this terrifies many people and provides extremists with the sort of alarmist rhetoric needed to grab power. We see these forces rushing headlong toward each other with society-wide conflict the impact. Progressive and conservative blocks are headed toward a massive fight. This also lines up along urban and rural lines, young and old, educated and uneducated. The future hangs in the balance and it is not clear who has the advantage.

Driving the conservatives to such heights of violence and fear are changes to society of massive scale. Demographics are driving the changes with people of color becoming impossible to ignore, along with an aging population. Sexual freedom has emboldened people to break free of traditional boundaries of behavior, gender and relationships. Technology is accelerating the change and empowering people in amazing ways. All of this terrifies many people and provides extremists with the sort of alarmist rhetoric needed to grab power. We see these forces rushing headlong toward each other with society-wide conflict the impact. Progressive and conservative blocks are headed toward a massive fight. This also lines up along urban and rural lines, young and old, educated and uneducated. The future hangs in the balance and it is not clear who has the advantage. maintain communication via text, audio or video with amazing ease. This starts to form different communities and relationships that are shaking culture. It’s mostly a middle class phenomenon and thus the poor are left out, and afraid.

maintain communication via text, audio or video with amazing ease. This starts to form different communities and relationships that are shaking culture. It’s mostly a middle class phenomenon and thus the poor are left out, and afraid. For example in my public life, I am not willing to give up the progress, and feel that the right wing is agitating to push the clock back. The right wing feels the changes are immoral and frightening and want to take freedom away. They will do it in the name of fighting terrorism while clutching the mantle of white nationalism and the Bible in the other hand. Similar mixes are present in Europe, Russia, and remarkably across the Arab world. My work World is increasingly allied with the forces against progress. I see a deep break in the not to distant future where the progress scientific research depends upon will be utterly incongruent with the values of my security-obsessed work place. The two things cannot live together effectively and ultimately the work will be undone by its inability to commit itself to being part of the modern World. The forces of progress are powerful and seemingly unstoppable too. We are seeing the unstoppable force of progress meet the immovable object of fear and oppression. It is going to be violent and sudden. My belief in progress is steadfast, and unwavering. Nonetheless, we have had episodes in human history where progress was stopped. Anyone heard of the dark ages? It can happen.

For example in my public life, I am not willing to give up the progress, and feel that the right wing is agitating to push the clock back. The right wing feels the changes are immoral and frightening and want to take freedom away. They will do it in the name of fighting terrorism while clutching the mantle of white nationalism and the Bible in the other hand. Similar mixes are present in Europe, Russia, and remarkably across the Arab world. My work World is increasingly allied with the forces against progress. I see a deep break in the not to distant future where the progress scientific research depends upon will be utterly incongruent with the values of my security-obsessed work place. The two things cannot live together effectively and ultimately the work will be undone by its inability to commit itself to being part of the modern World. The forces of progress are powerful and seemingly unstoppable too. We are seeing the unstoppable force of progress meet the immovable object of fear and oppression. It is going to be violent and sudden. My belief in progress is steadfast, and unwavering. Nonetheless, we have had episodes in human history where progress was stopped. Anyone heard of the dark ages? It can happen. work. This is delivered with disempowering edicts and policies that conspire to shackle me, and keep me from doing anything. The real message is that nothing you do is important enough to risk fucking up. I’m convinced that the things making work suck are strongly connected to everything else.

work. This is delivered with disempowering edicts and policies that conspire to shackle me, and keep me from doing anything. The real message is that nothing you do is important enough to risk fucking up. I’m convinced that the things making work suck are strongly connected to everything else. adapting and pushing themselves forward, the organization will stagnate or be left behind by the exciting innovations shaping the World today. When the motivation of the organization fails to emphasize productivity and efficiency, the recipe is disastrous. Modern technology offers the potential for incredible advances, but only if they’re seeking advantage. If minds are not open to making things better, it is a recipe for frustration.

adapting and pushing themselves forward, the organization will stagnate or be left behind by the exciting innovations shaping the World today. When the motivation of the organization fails to emphasize productivity and efficiency, the recipe is disastrous. Modern technology offers the potential for incredible advances, but only if they’re seeking advantage. If minds are not open to making things better, it is a recipe for frustration. unwittingly enter into the opposition to change, and assist the conservative attempt to hold onto the past.

unwittingly enter into the opposition to change, and assist the conservative attempt to hold onto the past. code. You found some really good problems that “go to eleven.” If you do things right, your code will eventually “break” in some way. The closer you look, the more likely it’ll be broken. Heck your code is probably already broken, and you just don’t know it! Once it’s broken, what should you do? How do you get the code back into working order? What can you do to figure out why it’s broken? How do you live with the knowledge of the limitations of the code? Those limitations are there, but usually you don’t know them very well. Essentially you’ve gone about the process of turning over rocks with your code until you find something awfully dirty-creepy crawly underneath. You then have mystery to solve, and/or ambiguity to live with from the results.

code. You found some really good problems that “go to eleven.” If you do things right, your code will eventually “break” in some way. The closer you look, the more likely it’ll be broken. Heck your code is probably already broken, and you just don’t know it! Once it’s broken, what should you do? How do you get the code back into working order? What can you do to figure out why it’s broken? How do you live with the knowledge of the limitations of the code? Those limitations are there, but usually you don’t know them very well. Essentially you’ve gone about the process of turning over rocks with your code until you find something awfully dirty-creepy crawly underneath. You then have mystery to solve, and/or ambiguity to live with from the results.

failures that can go unnoticed without expert attention. One of the key things is the loss of accuracy in a solution. This could be the numerical level of error being wrong, or the rate of convergence of the solution being outside the theoretical guarantees for the method (convergence rates are a function of the method and the nature of the solution itself). Sometimes this character is associated with an overly dissipative solution where numerical dissipation is too large to be tolerated. At this subtle level we are judging failure by a high standard based on knowledge and expectations driven by deep theoretical understanding. These failings generally indicate you are at a good level of testing and quality.

failures that can go unnoticed without expert attention. One of the key things is the loss of accuracy in a solution. This could be the numerical level of error being wrong, or the rate of convergence of the solution being outside the theoretical guarantees for the method (convergence rates are a function of the method and the nature of the solution itself). Sometimes this character is associated with an overly dissipative solution where numerical dissipation is too large to be tolerated. At this subtle level we are judging failure by a high standard based on knowledge and expectations driven by deep theoretical understanding. These failings generally indicate you are at a good level of testing and quality. methods. You should be intimately familiar with the conditions for stability for the code’s methods. You should assure that the stability conditions are not being exceeded. If a stability condition is missed, or calculated incorrectly, the impact is usually immediate and catastrophic. One way to do this on the cheap is modify the code’s stability condition to a more conservative version usually with a smaller safety factor. If the catastrophic behavior goes away then it points a finger at the stability condition with some certainty. Either the method is wrong, or not coded correctly, or you don’t really understand the stability condition properly. It is important to figure out which of these possibilities you’re subject to. Sometimes this needs to be studied using analytical techniques to examine the stability theoretically.

methods. You should be intimately familiar with the conditions for stability for the code’s methods. You should assure that the stability conditions are not being exceeded. If a stability condition is missed, or calculated incorrectly, the impact is usually immediate and catastrophic. One way to do this on the cheap is modify the code’s stability condition to a more conservative version usually with a smaller safety factor. If the catastrophic behavior goes away then it points a finger at the stability condition with some certainty. Either the method is wrong, or not coded correctly, or you don’t really understand the stability condition properly. It is important to figure out which of these possibilities you’re subject to. Sometimes this needs to be studied using analytical techniques to examine the stability theoretically. Another approach to take is systematically make the problem you’re solving easier until the results are “correct,” or the catastrophic behavior is replaced with something less odious. An important part of this process is more deeply understand how the problems are being triggered in the code. What sort of condition is being exceeded and how are the methods in the code going south? Is there something explicit that can be done to change the methodology so that this doesn’t happen? Ultimately, the issue is a systematic understanding of how the code and its method’s behave, their strengths and weaknesses. Once the weakness is exposed in the testing can you do something to get rid of it? Whether the weakness is a bug or feature of the code is another question to answer. Through the process of successively harder problems one can make the code better and better until you’re at the limits of knowledge.

Another approach to take is systematically make the problem you’re solving easier until the results are “correct,” or the catastrophic behavior is replaced with something less odious. An important part of this process is more deeply understand how the problems are being triggered in the code. What sort of condition is being exceeded and how are the methods in the code going south? Is there something explicit that can be done to change the methodology so that this doesn’t happen? Ultimately, the issue is a systematic understanding of how the code and its method’s behave, their strengths and weaknesses. Once the weakness is exposed in the testing can you do something to get rid of it? Whether the weakness is a bug or feature of the code is another question to answer. Through the process of successively harder problems one can make the code better and better until you’re at the limits of knowledge. Whether you are at the limits of knowledge takes a good deal of experience and study. You need to know the field and your competition quite well. You need to be willing to borrow from others and consider their success carefully. There is little time for pride, if you want to get to the frontier of capability; you need to be brutal and focused along the path. You need to keep pushing your code with harder testing and not be satisfied with the quality. Eventually you will get to problems that cannot be overcome with what people know how to do. At that point your methodology probably needs to evolve a bit. This is really hard work, and prone to risk and failure. For this reason most codes never get to this level of endeavor, its simply too hard on the code developers, and worse on those managing them. Today’s management of science simply doesn’t enable the level of risk and failure necessary to get to the summit of our knowledge. Management wants sure results and cannot deal with ambiguity at all, and striving at the frontier of knowledge is full of it, and usually ends up failing.

Whether you are at the limits of knowledge takes a good deal of experience and study. You need to know the field and your competition quite well. You need to be willing to borrow from others and consider their success carefully. There is little time for pride, if you want to get to the frontier of capability; you need to be brutal and focused along the path. You need to keep pushing your code with harder testing and not be satisfied with the quality. Eventually you will get to problems that cannot be overcome with what people know how to do. At that point your methodology probably needs to evolve a bit. This is really hard work, and prone to risk and failure. For this reason most codes never get to this level of endeavor, its simply too hard on the code developers, and worse on those managing them. Today’s management of science simply doesn’t enable the level of risk and failure necessary to get to the summit of our knowledge. Management wants sure results and cannot deal with ambiguity at all, and striving at the frontier of knowledge is full of it, and usually ends up failing. Another big issue is finding general purpose fixes for hard problems. Often the fix to a really difficult problem wrecks your ability to solve lots of other problems. Tailoring the solution to treat the difficulty and not destroy the ability to solve other easier problems is an art and the core of the difficulty in advancing the state of the art. The skill to do this requires fairly deep theoretical knowledge of a field study, along with exquisite understanding of the root of difficulties. The difficulty people don’t talk about is the willingness to attack the edge of knowledge and explicitly admit the limitations of what is currently done. This is an admission of weakness that our system doesn’t support. When fixes aren’t general purpose, one clear sign is a narrow range of applicability. If its not general purpose and makes a mess of existing methodology, you probably don’t really understand what’s going on.

Another big issue is finding general purpose fixes for hard problems. Often the fix to a really difficult problem wrecks your ability to solve lots of other problems. Tailoring the solution to treat the difficulty and not destroy the ability to solve other easier problems is an art and the core of the difficulty in advancing the state of the art. The skill to do this requires fairly deep theoretical knowledge of a field study, along with exquisite understanding of the root of difficulties. The difficulty people don’t talk about is the willingness to attack the edge of knowledge and explicitly admit the limitations of what is currently done. This is an admission of weakness that our system doesn’t support. When fixes aren’t general purpose, one clear sign is a narrow range of applicability. If its not general purpose and makes a mess of existing methodology, you probably don’t really understand what’s going on.

Fortunate are those who take the first steps.

Fortunate are those who take the first steps. Marty DiBergi: I don’t know.

Marty DiBergi: I don’t know. simplified versions of what we know brings the code to its knees, and serve as good blueprints for removing these issues from the code’s methods. Alternatively, they provide proof that certain pathological behaviors do or don’t exist in a code. Really brutal problems that “go to eleven” aid the development of methods by highlighting where improvement is needed clearly. Usually the simpler and cleaner problems are better because more codes and methods can run them, analysis is easier and we can successfully experiment with remedial measures. This allows more experimentation and attempts to solve it using diverse approaches. This can energize rapid progress and deeper understanding.

simplified versions of what we know brings the code to its knees, and serve as good blueprints for removing these issues from the code’s methods. Alternatively, they provide proof that certain pathological behaviors do or don’t exist in a code. Really brutal problems that “go to eleven” aid the development of methods by highlighting where improvement is needed clearly. Usually the simpler and cleaner problems are better because more codes and methods can run them, analysis is easier and we can successfully experiment with remedial measures. This allows more experimentation and attempts to solve it using diverse approaches. This can energize rapid progress and deeper understanding. I am a deep believer in the power of brutality at least when it comes to simulation codes. I am a deep believer that we are generally too easy on our computer codes; we should endeavor to break them early and often. A method or code is never “good enough”. The best way to break our codes is attempt to solve really hard problems that are beyond our ability to solve today. Once the solution of these brutal problems is well enough in hand, one should find a way of making the problem a little bit harder. The testing should actually be more extreme and difficult than anything we need to do with codes. One should always be working at, or beyond the edge of what can be done instead of safely staying within our capabilities. Today we are too prone to simply solving problems that are well in hand instead of pushing ourselves into the unknown. This tendency is harming progress.

I am a deep believer in the power of brutality at least when it comes to simulation codes. I am a deep believer that we are generally too easy on our computer codes; we should endeavor to break them early and often. A method or code is never “good enough”. The best way to break our codes is attempt to solve really hard problems that are beyond our ability to solve today. Once the solution of these brutal problems is well enough in hand, one should find a way of making the problem a little bit harder. The testing should actually be more extreme and difficult than anything we need to do with codes. One should always be working at, or beyond the edge of what can be done instead of safely staying within our capabilities. Today we are too prone to simply solving problems that are well in hand instead of pushing ourselves into the unknown. This tendency is harming progress.

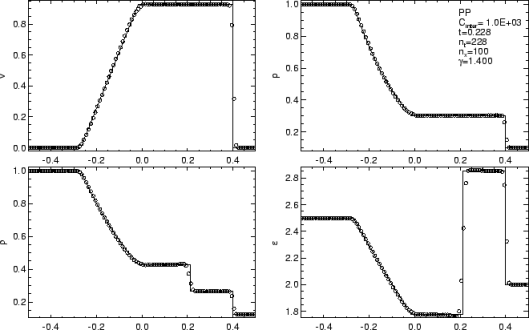

By the time a decade had passed after the introduction of Sod’s problem almost all of the pathological solutions we used to see had disappeared and far better methods existed (not because of Sod’s problem per se, but something was “in the air” too). The existence of a common problem to test and present results was a vehicle for the community to use in this endeavor. Today, the Sod problem is simply a “hello World” for shock physics and offers no real challenge to a serious method or code. It is difficult to distinguish between very good and OK solutions with results. Being able to solve the Sod problem doesn’t really qualify you to attack really hard problems either. It is a fine opening ante, but never the final call. The only problem with using the Sod problem today is that too many methods and codes stop their testing there and never move to the problems that challenge our knowledge and capability today. A key to making progress is to find problems where things don’t work so well, focus attention on changing that.

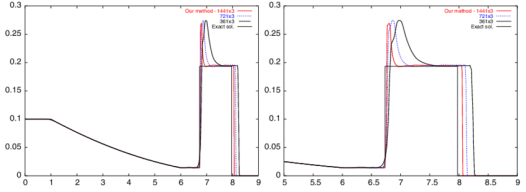

By the time a decade had passed after the introduction of Sod’s problem almost all of the pathological solutions we used to see had disappeared and far better methods existed (not because of Sod’s problem per se, but something was “in the air” too). The existence of a common problem to test and present results was a vehicle for the community to use in this endeavor. Today, the Sod problem is simply a “hello World” for shock physics and offers no real challenge to a serious method or code. It is difficult to distinguish between very good and OK solutions with results. Being able to solve the Sod problem doesn’t really qualify you to attack really hard problems either. It is a fine opening ante, but never the final call. The only problem with using the Sod problem today is that too many methods and codes stop their testing there and never move to the problems that challenge our knowledge and capability today. A key to making progress is to find problems where things don’t work so well, focus attention on changing that. Therefore, if we want problems to spur progress and shed light on what works, we need harder problems. For example, we could systematically up the magnitude of the variation in initial conditions in shock tube problems until results start to show issues. This usefully produces harder problems, but really hasn’t been done (note to self this is a really good idea). One problem that produces this comes from the National Lab community in the form of LeBlanc’s shock tube, or its more colorful colloquial name, “the shock tube from Hell.” This is a much less forgiving problem than Sod’s shock tube, and that is an understatement. Rather than jumps in pressure and density of about one order of magnitude, the jump in density is 1000-to-1 and the jump in pressure is one billion-to-one. This stresses methods far more than Sod and many simple methods can completely fail. Most industrial or production quality methods can actually solve the problem albeit with much more resolution than Sod’s problem requires (I’ve gotten decent results on Sod’s problem on mesh sequences of 4-8-16 cells!). For the most part we can solve LeBlanc’s problem capably today, so its time to look for fresh challenges.

Therefore, if we want problems to spur progress and shed light on what works, we need harder problems. For example, we could systematically up the magnitude of the variation in initial conditions in shock tube problems until results start to show issues. This usefully produces harder problems, but really hasn’t been done (note to self this is a really good idea). One problem that produces this comes from the National Lab community in the form of LeBlanc’s shock tube, or its more colorful colloquial name, “the shock tube from Hell.” This is a much less forgiving problem than Sod’s shock tube, and that is an understatement. Rather than jumps in pressure and density of about one order of magnitude, the jump in density is 1000-to-1 and the jump in pressure is one billion-to-one. This stresses methods far more than Sod and many simple methods can completely fail. Most industrial or production quality methods can actually solve the problem albeit with much more resolution than Sod’s problem requires (I’ve gotten decent results on Sod’s problem on mesh sequences of 4-8-16 cells!). For the most part we can solve LeBlanc’s problem capably today, so its time to look for fresh challenges. Other good problems are devised though knowing what goes wrong in practical calculation. Often those who know how to solve the problem create these problems. A good example is the issue of expansion shocks, which can be seen by taking Sod’s shock tube and introducing a velocity to the initial condition. This puts a sonic point (where the characteristic speed goes to zero) in the rarefaction. We know how to remove this problem by adding an “entropy” fix to the Riemann solver defining a class of methods that work. The test simply unveils whether the problem infests a code that may have ignored this issue. This detection is a very good side-effect of a well-designed test problem.

Other good problems are devised though knowing what goes wrong in practical calculation. Often those who know how to solve the problem create these problems. A good example is the issue of expansion shocks, which can be seen by taking Sod’s shock tube and introducing a velocity to the initial condition. This puts a sonic point (where the characteristic speed goes to zero) in the rarefaction. We know how to remove this problem by adding an “entropy” fix to the Riemann solver defining a class of methods that work. The test simply unveils whether the problem infests a code that may have ignored this issue. This detection is a very good side-effect of a well-designed test problem.

attacking something important and creating innovative solutions. I do a lot of things every day, but very little of it is either worthwhile or meaningful. At the same time I’m doing exactly what I am supposed to be doing! This means that my employer (or masters) are asking me to spend all of my valuable time doing meaningless, time wasting things as part of my conditions of employment. This includes trips to stupid, meaningless meetings with little or no content of value, compliance training, project planning, project reports, e-mails, jumping through hoops to get a technical paper, and a smorgasbord of other paperwork. Much of this is hoisted upon us by our governing agency, coupled with rampant institutional over-compliance, or managerially driven ass covering. All of this equals no time or focus on anything that actually matters squeezing out all the potential for innovation. Many of the direct actions result in creating an environment where risk and failure are not tolerated thus killing innovation before it can attempt to appear.

attacking something important and creating innovative solutions. I do a lot of things every day, but very little of it is either worthwhile or meaningful. At the same time I’m doing exactly what I am supposed to be doing! This means that my employer (or masters) are asking me to spend all of my valuable time doing meaningless, time wasting things as part of my conditions of employment. This includes trips to stupid, meaningless meetings with little or no content of value, compliance training, project planning, project reports, e-mails, jumping through hoops to get a technical paper, and a smorgasbord of other paperwork. Much of this is hoisted upon us by our governing agency, coupled with rampant institutional over-compliance, or managerially driven ass covering. All of this equals no time or focus on anything that actually matters squeezing out all the potential for innovation. Many of the direct actions result in creating an environment where risk and failure are not tolerated thus killing innovation before it can attempt to appear. only thing not required of me at work is actual productivity. All my training, compliance, and other work activities are focused on things that produce nothing of value. At some level we fail to respect our employees and end up wasting our lives by having us invest time in activities devoid of content and value. Basically the entire apparatus of my work is focused on forcing me to do things that produce nothing worthwhile other than providing a wage to support my family. Real productivity and innovation is all on me and increasingly a pro bono activity. The fact that actual productivity isn’t a concern for my employer is really fucked up. The bottom line is that we aren’t funded to do anything valuable, and the expectations on me are all bullshit and no substance. Its been getting steadily worse with each passing year too. When my employer talks about efficiency, it is all about saving money, not producing anything for the money we spend. Instead of focusing on producing more or better with the funding and unleashing the creative energy of people, we focus on penny pinching and making the workplace more unpleasant and genuinely terrible. None of the changes make for a better, more engaging workplace and simply continually reduce the empowerment of employees.

only thing not required of me at work is actual productivity. All my training, compliance, and other work activities are focused on things that produce nothing of value. At some level we fail to respect our employees and end up wasting our lives by having us invest time in activities devoid of content and value. Basically the entire apparatus of my work is focused on forcing me to do things that produce nothing worthwhile other than providing a wage to support my family. Real productivity and innovation is all on me and increasingly a pro bono activity. The fact that actual productivity isn’t a concern for my employer is really fucked up. The bottom line is that we aren’t funded to do anything valuable, and the expectations on me are all bullshit and no substance. Its been getting steadily worse with each passing year too. When my employer talks about efficiency, it is all about saving money, not producing anything for the money we spend. Instead of focusing on producing more or better with the funding and unleashing the creative energy of people, we focus on penny pinching and making the workplace more unpleasant and genuinely terrible. None of the changes make for a better, more engaging workplace and simply continually reduce the empowerment of employees. incremental at best. The result is a system where I am almost definitively not productive if I do exactly what I’m supposed to do. The entire apparatus of accountability is absurd and an insult to productive work. It sounds good, but its completely destructive, and we keep adding more and more of it.

incremental at best. The result is a system where I am almost definitively not productive if I do exactly what I’m supposed to do. The entire apparatus of accountability is absurd and an insult to productive work. It sounds good, but its completely destructive, and we keep adding more and more of it. ng me to be productive is to trust me. We need to realize that our systems at work are structured to deal with a lack of trust. Implicit in all the systems is a feeling that people need to be constantly being checked up on. If people aren’t constantly being checked up on they are fucking off. The result is an almost complete lack of empowerment, and a labyrinth of micromanagement. To be productive we need to be trusted, and we need to be empowered. We need to be chasing big important goals that we are committed to achieving. Once we accept the goals, we need to be unleashed to accomplish them. In the process we need to solve all sorts of problems, and in the process we can provide innovative solutions that enrich the knowledge of humanity and enrich society at large. This is a tried and true formula for progress that we have lost faith in, and with this lack of faith we have lost trust in our fellow citizens.

ng me to be productive is to trust me. We need to realize that our systems at work are structured to deal with a lack of trust. Implicit in all the systems is a feeling that people need to be constantly being checked up on. If people aren’t constantly being checked up on they are fucking off. The result is an almost complete lack of empowerment, and a labyrinth of micromanagement. To be productive we need to be trusted, and we need to be empowered. We need to be chasing big important goals that we are committed to achieving. Once we accept the goals, we need to be unleashed to accomplish them. In the process we need to solve all sorts of problems, and in the process we can provide innovative solutions that enrich the knowledge of humanity and enrich society at large. This is a tried and true formula for progress that we have lost faith in, and with this lack of faith we have lost trust in our fellow citizens. t they can’t be trusted. If people are treated like they can’t be trusted, you can’t expect them to be productive. To be better and productive, we need to start with a different premise. To be productive we need to center and focus our work on the producers, not the managers. We need to trust and put faith in each other to solve problems, innovate and create a better future.

t they can’t be trusted. If people are treated like they can’t be trusted, you can’t expect them to be productive. To be better and productive, we need to start with a different premise. To be productive we need to center and focus our work on the producers, not the managers. We need to trust and put faith in each other to solve problems, innovate and create a better future.