A very great deal more truth can become known than can be proven.

― Richard Feynman

In modeling and simulation verification is a set of activities broadly supporting the quality. Verification consists of two modes of practice: code verification where the mathematical correctness of the computer code is assessed, or solution (calculation) verification where the numerical error (uncertainty) is estimated. Both activities are closely linked to each other and they are utterly complementary in nature. To a large extent the methodology used for both types of verification are similar, but the differences between the two are important to maintain.

Modeling and simulation is an activity where continuous mathematics is converted to discrete computable quantities. This process involves approximation of the continuous mathematics and in almost every non-pathological circumstance is inexact. The core of modeling and simulation is the solution of (partial) differential equations using approximation methods. Code verification is a means of assuring that the approximations used to make the discrete solution of differential equations tractable on a computer are correct. A key aspect of code verification is determining that the discrete approximation of the differential equation is consistent with the continuous version of the differential equation.

Consistency demands that the order of approximation of the differential equation be at least one. In other words the discrete equations produce solutions that are the original continuous equations plus terms that are proportional to the size of the discretization. This character may be examined by solving problems with an exact analytical solution (or a problem with very well controlled and characterized errors) using several discretization sizes allowing the computation of errors, and determining the order of approximation. The combination of consistency and stability of the approximation means the approximation converges to the correct solution of the continuous differential equation.

We will examine both the nature of different types of problems to determine code verification and the methods of determining the order of approximation. One of the key aspects of code verification is the congruence of the theoretical order of accuracy for a method, and the observed order of accuracy. It is important to note that the theoretical order of convergence also depends upon the problem being solved. The problem must possess enough regularity to support the convergence rate expected. At this point it is important to point out that code verification produces both an order of approximation and an observed error in solution. Both of these quantities are important. For code verification, the order of approximation is the primary quantity of interest. It depends on both the nature of the approximation method and the problem being solved. If the problem being solved is insufficiently regular and smooth, the order of accuracy will not match the theoretical expectations of the method.

The second form of verification is solution verification. This is quite similar to code verification, but its aim is the estimation of approximation errors in a calculation. When one runs a problem without an analytical solution, the estimation of errors is more intricate. One looks at a series of solutions and compute the solution that is indicated by the sequence. Essentially the question of what solution is the approximation appearing to converge toward is being asked. If the sequence of solutions converges, the error in the solution can be inferred. As with code verification the order of convergence and the error is a product of the analysis. Conversely to the code verification, the error estimate is the primary quantity of interest, and the order of convergence is secondary.

The approach, procedure and methodology for both forms of verification are utterly complementary. Much of the mathematics and flow of work are shared in all verification, but details, pitfalls and key tips differ. In this post the broader themes of commonality are examined along with distinctions and a general rubric for each type of verification is discussed.

Code verification

Science replaces private prejudice with public, verifiable evidence.

― Richard Dawkins

When one conducts a code verification study there is a basic flow of activities and practices to conduct. One looks at a code to target and a problem to solve. Several key bits of information should be immediately being focused upon before the problem is solved. What is the order of accuracy for the method in the code being examined, and what is the order of accuracy that the problem being solved can expose? In addition the nature of the analytical solution to the problem should be carefully considered. For example what is the nature of the solution? Closed form? Series expansion? Numerical evaluation? Some of these forms of analytical solution have errors that must be controlled and assessed before the code’s method may be assessed. By the same token are there auxiliary aspects of the code’s solution that might pollute results? Solution of linear systems of equations? Stability issues? Computer roundoff or parallel computing issues? In each case these details could pollute results if not carefully excluded from consideration.

Next one needs to produce a solution on a sequence of meshes. For simple verification using a single discretization parameter only two discretizations are needed for verification (two equations to solve for two unknowns). For code verification the model for error is simple, generally a power law,

using a single discretization parameter only two discretizations are needed for verification (two equations to solve for two unknowns). For code verification the model for error is simple, generally a power law,  where the error is proportional to the discretization parameter

where the error is proportional to the discretization parameter  to the power (order)

to the power (order)  . There is also a constant of proportionality. The order,

. There is also a constant of proportionality. The order,  is the target of the study and one looks at its congruence with the expected theoretical order for the method on the problem being solved. It is almost always advisable to use more than the minimum number of meshes to assure that one simply isn’t examining anamolous behavior from the code.

is the target of the study and one looks at its congruence with the expected theoretical order for the method on the problem being solved. It is almost always advisable to use more than the minimum number of meshes to assure that one simply isn’t examining anamolous behavior from the code.

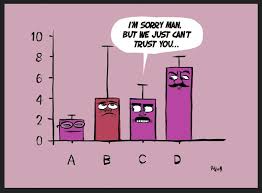

One of the problems with code verification is the rarity of the observed order of convergence to exactly match the expected order of convergence. The question of how close is close enough haunts investigations. Invariably the observed order will deviate from the expected order by some amount. The question for the practitioner is how close is acceptable? Generally this question is given little attention. There are more advanced verification techniques that can put this issue to rest by producing uncertainties on the observed order, but the standard techniques simply produce a single result. Usually this results in rules of thumb that apply in broad brushes, but undermine the credibility of the whole enterprise. Often the criterion is that the observed order should be within a tenth of the theoretically expected result.

Another key caveat comes up when the problem is discontinuous. In this case the observed order is either set to one for nonlinear solutions, or weakly tied to the theoretical order of convergence. For the wave equation this result was studied by Banks, Aslam and Rider and admits an analytical and firmly determined result. In both cases the issue of inexact congruence with the expected rate of convergence remains. In addition for problems involving systems of equations will have multiple features each having a separate order of convergence, and the rates will combine within a solution. Ultimately in an asymptotic sense the lowest order of convergence will dominate as  . This is quite difficult to achieve practically.

. This is quite difficult to achieve practically.

The last major issue that comes up in code verification (and solution verification too) is the nature of the discrete mesh and its connection to the asymptotic range of convergence. All of the theoretical results apply when the discretization parameter is small in a broad mathematical sense. This is quite problem specific and generally ill defined. Examining the congruence of the numerical derivatives of the analytical solution with the analytical derivatives can generally assess this. When these quantities are in close agreement, the solution can be considered to be asymptotic. Again these definitions are loose and generally applied with a large degree of professional or expert judgment.

It is useful to examine these issues through a concrete problem in code verification. The example I’ll use is a simple ordinary differential equation integrator for a linear equation  coded up in Mathematica. We could solve this problem in a spreadsheet (like MS Excel), python, or a standard programming language. The example will look at two first order methods, forwards

coded up in Mathematica. We could solve this problem in a spreadsheet (like MS Excel), python, or a standard programming language. The example will look at two first order methods, forwards

and backwards

and backwards  Euler methods. Both of these methods produce leading first order errors in an asymptotic sense,

Euler methods. Both of these methods produce leading first order errors in an asymptotic sense,  . If

. If  is large enough, the high order terms will pollute the error and produce deviations from the pure first-order error. Let’s look at this example and the concrete analysis from verification. This will be instructive in getting to similar problems encountered in general code verification.

is large enough, the high order terms will pollute the error and produce deviations from the pure first-order error. Let’s look at this example and the concrete analysis from verification. This will be instructive in getting to similar problems encountered in general code verification.

Here is the code

ForwardEuler[h_, T_, a_] :=

(

uo = 1;

t = 0.0;

While[t < T,

(* integration *)

t = t + h;

un = uo + a h uo;

Print[“t= “, t, ” u(t) = “, un, ” err = “, Abs[un – Exp[a t]]];

uo = un

];

)

BackwardEuler[h_, T_, a_] :=

(

uo = 1;

t = 0.0;

While[t < T,

(* integration *)

t = t + h;

un = uo/(1 + a h);

Print[“t= “, t, ” u(t) = “, un, ” err = “, Abs[un – Exp[a t]]];

uo = un

];

)

Let’s look at the forward Euler integrator for several different choices of  , different end times for the solution and number of discrete solutions using the method. We will do the same thing for the backwards Euler method, which is different because it is unconditionally stable with respect to step size. For this simple ODE, the method is stable to a stepsize of

, different end times for the solution and number of discrete solutions using the method. We will do the same thing for the backwards Euler method, which is different because it is unconditionally stable with respect to step size. For this simple ODE, the method is stable to a stepsize of  and we can solve the problem to two stopping times of

and we can solve the problem to two stopping times of  ,

,  and

and  . The analytical solution is always,

. The analytical solution is always,  . We can solve this problem using a set of step sizes,

. We can solve this problem using a set of step sizes,  .

.

I can give results for various pairs of step sizes with both integrators, and see some common pathologies that we must deal with. Even solving such a simple problem, with simple methods can prove difficult and prone to heavy interpretation (arguably the simplest problem with the simplest methods). Much different results are achieved when the problem is run until different stopping times. We see the impact of accumulated error (since I’m using Mathematica so aspects of round-off error are pushed aside). In these cases round-off error would be another complication. Furthermore the backward Euler method for multiple equations would involve a linear (or nonlinear) solution that itself has an error tolerance that may significantly impact verification results. We see good results for

of accumulated error (since I’m using Mathematica so aspects of round-off error are pushed aside). In these cases round-off error would be another complication. Furthermore the backward Euler method for multiple equations would involve a linear (or nonlinear) solution that itself has an error tolerance that may significantly impact verification results. We see good results for  and a systematic deviation for longer ending times. To get acceptable verification results would require much smaller step sizes (for longer calculations!). This shows how easy it is to scratch the surface of really complex behavior in verification that might mask correctly implemented methods. What isn’t so well appreciated is that this behavior is expected and amenable to analysis through standard methods extended to look for it.

and a systematic deviation for longer ending times. To get acceptable verification results would require much smaller step sizes (for longer calculations!). This shows how easy it is to scratch the surface of really complex behavior in verification that might mask correctly implemented methods. What isn’t so well appreciated is that this behavior is expected and amenable to analysis through standard methods extended to look for it.

| h |

FE T=1 |

FE T=10 |

FE T=100 |

BE T=1 |

BE T=10 |

BE T=100 |

| 1 |

1.64 |

0.03 |

~0 |

0.79 |

1.87 |

16.99 |

| 0.5 |

1.20 |

0.33 |

4e-07 |

0.88 |

1.54 |

11.78 |

| 0.25 |

1.08 |

0.65 |

0.002 |

0.93 |

1.30 |

7.17 |

| 0.125 |

1.04 |

0.83 |

0.05 |

0.96 |

1.16 |

4.07 |

| 0.0625 |

1.02 |

0.92 |

0.27 |

0.98 |

1.08 |

2.40 |

| 0.03125 |

1.01 |

0.96 |

0.55 |

0.99 |

1.04 |

1.63 |

Computed order of convergence for forward Euler (FE) and backward Euler (BE) methods for various stopping times and step sizes.

Types of Code Verification Problems and Associated Data

Don’t give people what they want, give them what they need.

― Joss Whedon

The problem types are categorized by the difficulty of providing a solution coupled with the quality of the solution that can be obtained. These two concepts go hand-in-hand. As simple closed form solution is easy to obtain and evaluation. Conversely, a numerical solution of partial differential equations is difficult and carries a number of serious issues regarding its quality and trustworthiness. These issues are addressed by an increased level of scrutiny on evidence provided by associated data. Each of benchmark is not necessarily analytical in nature, and the solutions are each constructed in different means with different expected levels of quality and accompanying data. This necessitates the differences in level of required documentation and accompanying supporting material to assure the user of its quality.

the quality of the solution that can be obtained. These two concepts go hand-in-hand. As simple closed form solution is easy to obtain and evaluation. Conversely, a numerical solution of partial differential equations is difficult and carries a number of serious issues regarding its quality and trustworthiness. These issues are addressed by an increased level of scrutiny on evidence provided by associated data. Each of benchmark is not necessarily analytical in nature, and the solutions are each constructed in different means with different expected levels of quality and accompanying data. This necessitates the differences in level of required documentation and accompanying supporting material to assure the user of its quality.

Next, we provide a list of types of benchmarks along with an archetypical example of each. This is intended to be instructive to the experienced reader, who may recognize the example. The list is roughly ordered in increasing level of difficulty and need for greater supporting material.

- Closed form analytical solution (usually algebraic in nature). Example: Incompressible, unsteady, 2-D, laminar flow over an oscillating plate (Stokes oscillating plate) given in Panton, R. L. (1984). Incompressible Flow, New York, John Wiley, pp. 266-272.

- Analytical solution with significantly complex numerical evaluation

- Series solution. Example: Numerous classical problems, in H. Lamb’s book, “Hydrodynamics,” Dover, 1932. Classical separation of variables solution to heat conduction. Example: Incompressible, unsteady, axisymmetric 2-D, laminar flow in a circular tube impulsively started (Szymanski flow), given in White, F. M. (1991). Viscous Fluid Flow, New York, McGraw Hill, pp. 133-134.

- Nonlinear algebraic solution. Example: The Riemann shock tube problem, J. Gottleib, C. Groth, “Assessment of Riemann solvers for unsteady one-dimensional inviscid flows of perfect gases,” Journal of Computational Physics, 78(2), pp. 437-458, 1988.

- A similarity solution requiring a numerical solution of nonlinear ordinary differential equations.

- Manufactured Solution. Example: Incompressible, steady, 2-D, turbulent, wall-bounded flow with two turbulence models (makes no difference to me), given in Eça, L., M. Hoekstra, A. Hay and D. Pelletier (2007). “On the construction of manufactured solutions for one and two-equation eddy-viscosity models.” International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids. 54(2), 119-154.

- Highly accurate numerical solution (not analytical). Example: Incompressible, steady, 2-D, laminar stagnation flow on a flat plate (Hiemenz flow), given in White, F. M. (1991). Viscous Fluid Flow, New York, McGraw Hill. pp. 152-157.

- Numerical benchmark with an accurate numerical solution. Example: Incompressible, steady, 2-D, laminar flow in a driven cavity (with the singularities removed), given in Prabhakar, V. and J. N. Reddy (2006). “Spectral/hp Penalty Least-Squares Finite Element Formulation for the Steady Incompressible Navier-Stokes Equations.” Journal of Computational Physics. 215(1), 274-297.

- Code-to-code comparison data. Example: Incompressible, steady, 2-D, laminar flow over a back-step, given in Gartling, D. K. (1990). “A Test Problem for Outflow Boundary Conditions-Flow Over a Backward-Facing Step.” International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids. 11, 953-967.

Below is a list of the different types of data associated with verification problems defined above. Depending on the nature of the test problem only a subset of these data are necessary. This will be provided below the list of data types. As noted above, benchmarks with well-defined closed form analytical solutions require relatively less data than a benchmark associated with the approximate numerical solution of PDEs.

- Detailed technical description of the problem (report or paper)

- Analysis of the mathematics of the problem (report or paper)

- Computer analysis of solution (input file)

- Computer solution of the mathematical solution

- Computer implementation of the numerical solution

- Error analysis of the “exact” numerical solution

- Derivation of the source term and software implementation or input

- Computer implementation of the source term (manufactured solution)

- Grids for numerical solution

- Convergence and error estimation of approximate numerical solution

- Uncertainty and sensitivity study of numerical solution

- Description and analysis of computational methods

- Numerical analysis theory associated with convergence

- Code description/manuals

- Input files for problems and auxiliary software

- Patch test description, Derivation, input and analysis

- Unusual boundary conditions (inflow, piston, etc.…)

- Physics restrictions (boundary layer theory, inviscid,)

- Software quality documents

- Scripts and auxiliary software for verification

- Source code

- Metric descriptions

- Verification results including code version, date, etc.

- Numerical sensitivity studies

- Feature coverage in verification

Below, we briefly describe the characteristics of each type of benchmark documentation (could be called artifacts or meta-data) associated with a code verification benchmarks. These artifacts take a number of concrete forms such as a written document, computer code, mathematical solution in document or software form, input files for executable codes, input to automatic computer analysis, output from software quality systems, among others.

- Detailed technical description of the benchmark (report or paper): This can include a technical paper in a journal or conference proceeding describing the benchmark and its solution. Another form would be a report informal or formal from an institution providing the same information.

- Analysis of the mathematics (report or paper): For any solution that is closed form, or requiring a semi-analytical solution, the mathematics must be described in detail. This can be included in the paper (report) discussed previously or in a separate document.

- Computer analysis of solution (input file): If the mathematics or solution is accomplished using a computerized analysis, the program used and the input to the program should be included. Some sort of written documentation such as a manual for the software ideally accompanies this artifact.

- Computer solution of the mathematical solution: The actual computerized solution of the mathematical problem should be included in whatever form the computerized solution takes. This should include any error analysis completed with this solution.

- Computer implementation of the numerical solution: The analytical solution should be implemented in a computational form to allow the comparison with the numerical solution. This should include some sort of error analysis in the form of a report.

- Derivation of the source term and software implementation or input: In the case of the method of manufactured solutions, the source term used to drive the numerical method must be derived through a well-defined numerical procedure. This should be documented through a document, and numerical tools used for the derivation and implementation.

- Computer implementation of the source term (manufactured solution): The source term should be included in a form amenable to direct use in a computer code. The language for the computer code should be clearly defined as well as the compiler and computer system used.

- Grids for numerical solution: If a solution is computed using another simulation code all relevant details on the numerical grid(s) used must be included. This could be direct grid files, or input files to well-defined grid generation software.

- Convergence and error estimation of numerical solution: The numerical solution must include a convergence study and error estimate. These should be detailed in an appropriately peer-reviewed document.

- Uncertainty and sensitivity study of numerical solution: The various modeling options in the code used to provide the numerical solution must be examined vis-a-vis the uncertainty and sensitivity of the solution to these choices. This study should be used to justify the methodology used for the baseline solution.

- Description and analysis of computational methods: The methods used by the code used for the baseline solution must be completely described and analyzed. This can take the form of a complete bibliography of readily available literature

- Numerical analysis theory associated with convergence: The nature of the convergence and the magnitude of error in the numerical solution must be described and demonstrated. This can take the form of a complete bibliography of readily available literature.

- Code description/manuals: The code manual and complete description must be included with the analysis and description.

- Input files for benchmarks and auxiliary software: The input file used to produce the solution must be included. Any auxiliary software used to produce or analyze the solution must be full described or included.

- Unusual boundary conditions (inflow, piston, outflow, Robin, symmetry, …): Should the benchmark require unusual or involved boundary or initial conditions, these must be described in additional detail including the nature of implementation.

- Physics restrictions (boundary layer theory, inviscid, parabolized Navier-Stokes, …): If the solution requires the solution of a reduced or restricted set of equations, this must be fully described. Examples are boundary layer theory, truly inviscid flow, or various asymptotic limits.

- Software quality documents: Of non-commercial software used to produce solutions, the software quality pedigree should be clearly established by documenting the software quality and steps taken to assure the maintenance of the quality.

- Scripts and auxiliary software for verification: Auxiliary software or scripts used to determine the verification or compute error estimates for a software used to produce solution should be included.

- Source code: If possible the actual source code for the software along with instructions for producing an executable (makefile, scripts) should be included with all other documentation.

- A full mathematical or computational description of metrics used in error analysis and evaluation of solution implementation or numerical solution.

- Verification results including code version, date, and other identifying characteristics: The verification basis for the code used to produce the baseline solution must be included. This includes any documentation of verification, peer-review, code version, date completed and error estimates.

- Feature coverage in verification: The code features covered by verification benchmarks must be documented. Any gaps where the feature used for the baseline solution are not verified must be explicitly documented.

Below are the necessary data requirements for each category of benchmark, again arranged in order of increasing level of documentation required. For completeness each data type would expected to be available to describe a benchmark of a given type.

- Common elements for all types of benchmarks (it is notable that the use of proper verification using an analytical solution results in the most compact set of requirements for data, manufactured solutions also).

- Paper or report

- Mathematical analysis

- Computerized solution and input

- Error and uncertainty analysis

- Computer implementation of the evaluation of the solution

- Restrictions

- Boundary or initial conditions

- Closed form analytical solution

- Paper or report

- Mathematical analysis

- Computerized solution and input

- Error and uncertainty analysis

- Computer implementation of the evaluation of the solution

- Restrictions

- Boundary or initial conditions

- Paper or report

- Mathematical analysis

- Computational solution and input

- Error and uncertainty analysis

- Computer implementation of the evaluation of the solution

- Derivation and implementation of the source term

- Restrictions

- Boundary or initial conditions

- Numerical solution with analytical solution

- Series solution, Nonlinear algebraic solution, Nonlinear ODE solution

- Paper or report

- Mathematical analysis

- Computerized solution and input

- Error and uncertainty analysis

- Computer implementation of the evaluation of the solution

- Input files

- Source code

- Source code SQA

- Method description and manual

- Restrictions

- Boundary or initial conditions

- Highly accurate numerical solution (not analytical), numerical benchmarks or code-to-code comparisons.

- Paper or report

- Mathematical analysis

- Computational solution and input

- Error and uncertainty analysis for the solution

- Computer implementation of the evaluation of the solution

- Input files

- Grids

- Source code

- Source code SQA

- Method description and manual

- Method analysis

- Method verification analysis and coverage

- Restrictions

- Boundary or initial conditions

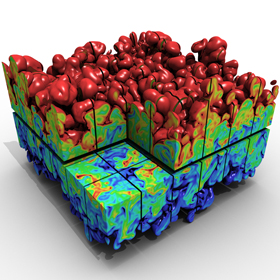

The use of direct numerical simulation requires a similar or even higher level of documentation than analytical solutions. This coincides with the discussion of the last type of verification benchmark where a complex numerical method with significant approximations is utilized to produce the solution. As a numerically computed benchmark, the burden of proof is much larger. Code verification is best served by exact analytical solutions because of the relative ease in assuring benchmark solution accuracy. Nonetheless, it remains a common practice due to its inherent simplicity. It also appeals to those who have a vested interest in the solutions produced by a certain computer code. The credibility of the comparison is predicated on the credibility of the code producing the “benchmark” used as the surrogate for truth. Therefore the documentation of the benchmark must provide the basis for the credibility.

The use of DNS as a surrogate for experimental data has received significant attention. This practice violates the fundamental definition of validation we have adopted because no observation of the physical world is used to define the data. This practice also raises other difficulties, which we will elaborate upon. First the DNS code itself requires that the verification basis further augmented by a validation basis for its application. This includes all the activities that would define a validation study including experimental uncertainty analysis numerical and physical equation based error analysis. Most commonly, the DNS serves to provide validation, but the DNS contains approximation errors that must be estimated as part of the “error bars” for the data. Furthermore, the code must have documented credibility beyond the details of the calculation used as data. This level of documentation again takes the form of the last form of verification benchmark introduced above because of the nature of DNS codes. For this reason we include DNS as a member of this family of benchmarks.

The use of DNS as a surrogate for experimental data has received significant attention. This practice violates the fundamental definition of validation we have adopted because no observation of the physical world is used to define the data. This practice also raises other difficulties, which we will elaborate upon. First the DNS code itself requires that the verification basis further augmented by a validation basis for its application. This includes all the activities that would define a validation study including experimental uncertainty analysis numerical and physical equation based error analysis. Most commonly, the DNS serves to provide validation, but the DNS contains approximation errors that must be estimated as part of the “error bars” for the data. Furthermore, the code must have documented credibility beyond the details of the calculation used as data. This level of documentation again takes the form of the last form of verification benchmark introduced above because of the nature of DNS codes. For this reason we include DNS as a member of this family of benchmarks.

There are two ways to do great mathematics. The first is to be smarter than everybody else. The second way is to be stupider than everybody else — but persistent.

― Raoul Bott

Banks, Jeffrey W., T. Aslam, and William J. Rider. “On sub-linear convergence for linearly degenerate waves in capturing schemes.” Journal of Computational Physics 227, no. 14 (2008): 6985-7002.

Greenough, J. A., and W. J. Rider. “A quantitative comparison of numerical methods for the compressible Euler equations: fifth-order WENO and piecewise-linear Godunov.” Journal of Computational Physics 196, no. 1 (2004): 259-281.

Kamm, James R., Jerry S. Brock, Scott T. Brandon, David L. Cotrell, Bryan Johnson, Patrick Knupp, W. Rider, T. Trucano, and V. Gregory Weirs. Enhanced verification test suite for physics simulation codes. No. LLNL-TR-411291. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), Livermore, CA, 2008.

Rider, J., James R. Kamm, and V. Gregory Weirs. “Verification, Validation and Uncertainty Quantification Workflow in CASL.” Albuquerque, NM: Sandia National Laboratories (2010).

Rider, William J., James R. Kamm, and V. Gregory Weirs. “Procedures for Calculation Verification.” Simulation Credibility (2016): 31.

The largest portion and most important part of this process is the analysis that allows us to answer the question. Often the question needs to be broken down into a series of simpler questions some of which are amenable to easier solution. This process is hierarchical and cyclical. Sometimes the process forces us to step back and requires us to ask an even better or more proper question. In sense this is the process working in full with the better and more proper question being an act of creation and understanding. The analysis requires deep work and often study, research and educating oneself. A new question will force one to take the knowledge one has and combine it with new techniques producing enhanced capabilities. This process is on the job education, and fuels personal growth and personal growth fuels excellence. When you are answering a completely new question, you are doing research and helping to push the frontiers of science forward. When you are answering an old question, you are learning and you might answer the question in a new way yielding new understanding. At worst, you are growing as a person and professional.

The largest portion and most important part of this process is the analysis that allows us to answer the question. Often the question needs to be broken down into a series of simpler questions some of which are amenable to easier solution. This process is hierarchical and cyclical. Sometimes the process forces us to step back and requires us to ask an even better or more proper question. In sense this is the process working in full with the better and more proper question being an act of creation and understanding. The analysis requires deep work and often study, research and educating oneself. A new question will force one to take the knowledge one has and combine it with new techniques producing enhanced capabilities. This process is on the job education, and fuels personal growth and personal growth fuels excellence. When you are answering a completely new question, you are doing research and helping to push the frontiers of science forward. When you are answering an old question, you are learning and you might answer the question in a new way yielding new understanding. At worst, you are growing as a person and professional. Once this creation is available, new questions can be posed and solved. These creations allow new questions to be asked answered. This is the way of progress where technology and knowledge builds the bridge something better. If we support excellence and a process like this, we will progress. Without support for this process, we simply stagnate and whither away. The choice is simple either embrace excellence by loosening control, or chain people to mediocrity.

Once this creation is available, new questions can be posed and solved. These creations allow new questions to be asked answered. This is the way of progress where technology and knowledge builds the bridge something better. If we support excellence and a process like this, we will progress. Without support for this process, we simply stagnate and whither away. The choice is simple either embrace excellence by loosening control, or chain people to mediocrity.

exact solution. This makes it a more difficult task than code verification where an exact solution is known removing a major uncertainty. A secondary issue associated with not knowing the exact solution is the implications on the nature of the solution itself. With an exact solution, a mathematical structure exists allowing the solution to be achievable analytically. Furthermore, exact solutions are limited to relatively simple models that often cannot model reality. Thus, the modeling approach to which solution verification is applied is necessarily more complex. All of these factors are confounding and produce a more perilous environment to conduct verification. The key product of solution verification is an estimate of numerical error and the secondary product is the rate of convergence. Both of these quantities are important to consider in the analysis.

exact solution. This makes it a more difficult task than code verification where an exact solution is known removing a major uncertainty. A secondary issue associated with not knowing the exact solution is the implications on the nature of the solution itself. With an exact solution, a mathematical structure exists allowing the solution to be achievable analytically. Furthermore, exact solutions are limited to relatively simple models that often cannot model reality. Thus, the modeling approach to which solution verification is applied is necessarily more complex. All of these factors are confounding and produce a more perilous environment to conduct verification. The key product of solution verification is an estimate of numerical error and the secondary product is the rate of convergence. Both of these quantities are important to consider in the analysis.

three unknowns,

three unknowns,  There are several practical issues related to this whole thread of discussion. One often encountered and extremely problematic issue is insanely high convergence rates. After one has been doing verification or seeing others do verification for a while, the analysis will sometimes provide an extremely high convergence rate. For example a second order method used to solve a problem will produce a sequence that produces a seeming 15th order solution (this example is given later). This is a ridiculous and results in woeful estimates of numerical error. A result like this usually indicates a solution on a tremendously unresolved mesh, and a generally unreliable simulation. This is one of those things that analysts should be mindful of. Constrained solution of the nonlinear equations can mitigate this possibility and exclude it a priori. This general approach including the solution with other norms, constraints and other aspects is explored in the paper on Robust Verification. The key concept is the solution to the error estimation problem is not unique and highly dependent upon assumptions. Different assumptions lead to different results to the problem and can be harnessed to make the analysis more robust and impervious to issues that might derail it.

There are several practical issues related to this whole thread of discussion. One often encountered and extremely problematic issue is insanely high convergence rates. After one has been doing verification or seeing others do verification for a while, the analysis will sometimes provide an extremely high convergence rate. For example a second order method used to solve a problem will produce a sequence that produces a seeming 15th order solution (this example is given later). This is a ridiculous and results in woeful estimates of numerical error. A result like this usually indicates a solution on a tremendously unresolved mesh, and a generally unreliable simulation. This is one of those things that analysts should be mindful of. Constrained solution of the nonlinear equations can mitigate this possibility and exclude it a priori. This general approach including the solution with other norms, constraints and other aspects is explored in the paper on Robust Verification. The key concept is the solution to the error estimation problem is not unique and highly dependent upon assumptions. Different assumptions lead to different results to the problem and can be harnessed to make the analysis more robust and impervious to issues that might derail it. Before moving to examples of solution verification we will show how robust verification can be used for code verification work. Since the error is known, the only uncertainty in the analysis is the rate of convergence. As we can immediately notice that this technique will get rid of a crucial ambiguity in the analysis. In standard code verification analysis, the rate of convergence is never the exact formal order, and expert judgment is used to determine if the results is close enough. With robust verification, the convergence rate has an uncertainty and the question of whether the exact value is included in the uncertainty band can be asked. Before showing the results for this application of robust verification, we need to note that the exact rate of verification is only the asymptotic rate in the limit of

Before moving to examples of solution verification we will show how robust verification can be used for code verification work. Since the error is known, the only uncertainty in the analysis is the rate of convergence. As we can immediately notice that this technique will get rid of a crucial ambiguity in the analysis. In standard code verification analysis, the rate of convergence is never the exact formal order, and expert judgment is used to determine if the results is close enough. With robust verification, the convergence rate has an uncertainty and the question of whether the exact value is included in the uncertainty band can be asked. Before showing the results for this application of robust verification, we need to note that the exact rate of verification is only the asymptotic rate in the limit of  s study using some initial grids that were known to be inadequate. One of the codes was relatively well trusted for this class of applications and produced three solutions that for all appearances appeared reasonable. One of the key parameters is the pressure drop through the test section. Using grids 664K, 1224K and 1934K elements we got pressure drops of 31.8 kPa, 24.6 kPa and 24.4 kPa respectively. Using a standard curve fitting for the effective mesh resolution gave an estimate of 24.3 kPa±0.0080 kPa for the resolved pressure drop and a convergence rate of 15.84. This is an absurd result and needs to simply be rejected immediately. Using the robust verification methodology on the same data set, gives a pressure drop of 16.1 kPa±13.5 kPa with a convergence rate of 1.23, which is reasonable. Subsequent calculations on refined grids produced results that were remarkably close to this estimate confirming the power of the technique even when given data that was substantially corrupted.

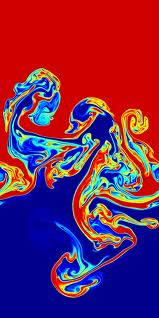

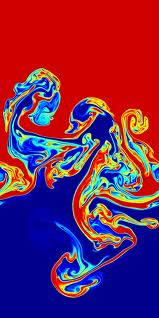

s study using some initial grids that were known to be inadequate. One of the codes was relatively well trusted for this class of applications and produced three solutions that for all appearances appeared reasonable. One of the key parameters is the pressure drop through the test section. Using grids 664K, 1224K and 1934K elements we got pressure drops of 31.8 kPa, 24.6 kPa and 24.4 kPa respectively. Using a standard curve fitting for the effective mesh resolution gave an estimate of 24.3 kPa±0.0080 kPa for the resolved pressure drop and a convergence rate of 15.84. This is an absurd result and needs to simply be rejected immediately. Using the robust verification methodology on the same data set, gives a pressure drop of 16.1 kPa±13.5 kPa with a convergence rate of 1.23, which is reasonable. Subsequent calculations on refined grids produced results that were remarkably close to this estimate confirming the power of the technique even when given data that was substantially corrupted. Our final example is a simple case of validation using the classical phenomena of vortex shedding over a cylinder at a relatively small Reynolds number. This is part of a reasonable effort to validate a research code before using in on more serious problems. The key experimental value to examine is the Stouhal number defined,

Our final example is a simple case of validation using the classical phenomena of vortex shedding over a cylinder at a relatively small Reynolds number. This is part of a reasonable effort to validate a research code before using in on more serious problems. The key experimental value to examine is the Stouhal number defined,

using a single discretization parameter only two discretizations are needed for verification (two equations to solve for two unknowns). For code verification the model for error is simple, generally a power law,

using a single discretization parameter only two discretizations are needed for verification (two equations to solve for two unknowns). For code verification the model for error is simple, generally a power law,  of accumulated error (since I’m using Mathematica so aspects of round-off error are pushed aside). In these cases round-off error would be another complication. Furthermore the backward Euler method for multiple equations would involve a linear (or nonlinear) solution that itself has an error tolerance that may significantly impact verification results. We see good results for

of accumulated error (since I’m using Mathematica so aspects of round-off error are pushed aside). In these cases round-off error would be another complication. Furthermore the backward Euler method for multiple equations would involve a linear (or nonlinear) solution that itself has an error tolerance that may significantly impact verification results. We see good results for  the quality of the solution that can be obtained. These two concepts go hand-in-hand. As simple closed form solution is easy to obtain and evaluation. Conversely, a numerical solution of partial differential equations is difficult and carries a number of serious issues regarding its quality and trustworthiness. These issues are addressed by an increased level of scrutiny on evidence provided by associated data. Each of benchmark is not necessarily analytical in nature, and the solutions are each constructed in different means with different expected levels of quality and accompanying data. This necessitates the differences in level of required documentation and accompanying supporting material to assure the user of its quality.

the quality of the solution that can be obtained. These two concepts go hand-in-hand. As simple closed form solution is easy to obtain and evaluation. Conversely, a numerical solution of partial differential equations is difficult and carries a number of serious issues regarding its quality and trustworthiness. These issues are addressed by an increased level of scrutiny on evidence provided by associated data. Each of benchmark is not necessarily analytical in nature, and the solutions are each constructed in different means with different expected levels of quality and accompanying data. This necessitates the differences in level of required documentation and accompanying supporting material to assure the user of its quality. The use of DNS as a surrogate for experimental data has received significant attention. This practice violates the fundamental definition of validation we have adopted because no observation of the physical world is used to define the data. This practice also raises other difficulties, which we will elaborate upon. First the DNS code itself requires that the verification basis further augmented by a validation basis for its application. This includes all the activities that would define a validation study including experimental uncertainty analysis numerical and physical equation based error analysis. Most commonly, the DNS serves to provide validation, but the DNS contains approximation errors that must be estimated as part of the “error bars” for the data. Furthermore, the code must have documented credibility beyond the details of the calculation used as data. This level of documentation again takes the form of the last form of verification benchmark introduced above because of the nature of DNS codes. For this reason we include DNS as a member of this family of benchmarks.

The use of DNS as a surrogate for experimental data has received significant attention. This practice violates the fundamental definition of validation we have adopted because no observation of the physical world is used to define the data. This practice also raises other difficulties, which we will elaborate upon. First the DNS code itself requires that the verification basis further augmented by a validation basis for its application. This includes all the activities that would define a validation study including experimental uncertainty analysis numerical and physical equation based error analysis. Most commonly, the DNS serves to provide validation, but the DNS contains approximation errors that must be estimated as part of the “error bars” for the data. Furthermore, the code must have documented credibility beyond the details of the calculation used as data. This level of documentation again takes the form of the last form of verification benchmark introduced above because of the nature of DNS codes. For this reason we include DNS as a member of this family of benchmarks.

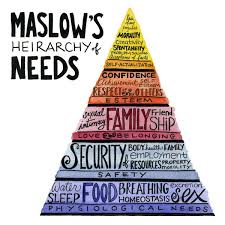

achieve a degree of access to resources that raise their access to a good life. With more resources the citizens can aspire toward a better, easier more fulfilled life. In essence the security of a Nation can allow people to exist higher on Maslow’s hierarchy needs. In the United States this is commonly expressed as “freedom”. Freedom is a rather superficial thing when used as a slogan. The needs of the citizens begin with having food and shelter than allow them to aspire toward a sense of personal safety. Societal safety is one means of achieving this (not that safety and security are pretty low on the hierarchy). With these in hand, the sense of community can be pursued and then sense of an esteemed self. Finally we get to the peak and the ability to pursue ones full personal potential.

achieve a degree of access to resources that raise their access to a good life. With more resources the citizens can aspire toward a better, easier more fulfilled life. In essence the security of a Nation can allow people to exist higher on Maslow’s hierarchy needs. In the United States this is commonly expressed as “freedom”. Freedom is a rather superficial thing when used as a slogan. The needs of the citizens begin with having food and shelter than allow them to aspire toward a sense of personal safety. Societal safety is one means of achieving this (not that safety and security are pretty low on the hierarchy). With these in hand, the sense of community can be pursued and then sense of an esteemed self. Finally we get to the peak and the ability to pursue ones full personal potential. . If one exists at this level, life isn’t very good, but its achievement is necessary for a better life. Gradually one moves up the hierarchy requiring greater access to resources and ease of maintaining the lower positions on the hierarchy. A vibrant National Security should allow this to happen, the richer a Nation becomes the higher on the hierarchy of needs its citizens reside. It is with some recognition of irony that my efforts and the Nation is stuck at such a low level on the hierarchy. Efforts toward bolstering the community the Nation forms seem to be too difficult to achieve today. We seem to be regressing from being a community or achieving personal fulfillment. We are stuck trying to be safe and secure. The question is whether those in the Nation can effectively provide the basis for existing high on the hierarchy of needs without being there themselves?

. If one exists at this level, life isn’t very good, but its achievement is necessary for a better life. Gradually one moves up the hierarchy requiring greater access to resources and ease of maintaining the lower positions on the hierarchy. A vibrant National Security should allow this to happen, the richer a Nation becomes the higher on the hierarchy of needs its citizens reside. It is with some recognition of irony that my efforts and the Nation is stuck at such a low level on the hierarchy. Efforts toward bolstering the community the Nation forms seem to be too difficult to achieve today. We seem to be regressing from being a community or achieving personal fulfillment. We are stuck trying to be safe and secure. The question is whether those in the Nation can effectively provide the basis for existing high on the hierarchy of needs without being there themselves? opportune time. Moore’s law is dead, and may be dead at all scales of computation. It may be the highest hanging fruit pursued at great cost while lower hanging fruits rots away without serious attention, or even conscious neglect. Perhaps nothing typifies this issue more than the state of validation in modeling and simulation.

opportune time. Moore’s law is dead, and may be dead at all scales of computation. It may be the highest hanging fruit pursued at great cost while lower hanging fruits rots away without serious attention, or even conscious neglect. Perhaps nothing typifies this issue more than the state of validation in modeling and simulation.

“What is a model?”

“What is a model?”  To conduct a validation assessment you need observations to compare to. This is an absolute necessity; if you have no observational data, you have no validation. Once the data is at hand, you need to understand how good it is. This means understanding how uncertain the data is. This uncertainty can come from three major aspects of the process: errors in measurement, errors in statistics, and errors in interpretation. In the order of how these were mentioned each of these categories become more difficult to assess and less common to actually be assessed in practice. Most commonly assessed is measurement error that is the uncertainty of the value of a measured quantity. This is a function of the measurement technology or the inference of the quantity from other data. The second aspect is associated with the statistical nature of the measurement. Is the observation or experiment repeatable? If it is not how much might the measured value differ due to changes in the system being observed? How typical are the measured values? In many cases this issue is ignored in a willfully ignorant manner. Finally, the hardest part of observational bias often defined as answering the question, “how do we know that we a measuring what we think we are?” Is there something systematic in our observed system that we have not accounted for that might be changing our observations. This may come from some sort of problem in calibrating measurements, or looking at the observed system in a manner that is inconsistent. These all lead to potential bias and distortion of the measurements.

To conduct a validation assessment you need observations to compare to. This is an absolute necessity; if you have no observational data, you have no validation. Once the data is at hand, you need to understand how good it is. This means understanding how uncertain the data is. This uncertainty can come from three major aspects of the process: errors in measurement, errors in statistics, and errors in interpretation. In the order of how these were mentioned each of these categories become more difficult to assess and less common to actually be assessed in practice. Most commonly assessed is measurement error that is the uncertainty of the value of a measured quantity. This is a function of the measurement technology or the inference of the quantity from other data. The second aspect is associated with the statistical nature of the measurement. Is the observation or experiment repeatable? If it is not how much might the measured value differ due to changes in the system being observed? How typical are the measured values? In many cases this issue is ignored in a willfully ignorant manner. Finally, the hardest part of observational bias often defined as answering the question, “how do we know that we a measuring what we think we are?” Is there something systematic in our observed system that we have not accounted for that might be changing our observations. This may come from some sort of problem in calibrating measurements, or looking at the observed system in a manner that is inconsistent. These all lead to potential bias and distortion of the measurements. The intrinsic benefit of this approach is a systematic investigation of the ability of the model to produce the features of reality. Ultimately the model needs to produce the features of reality that we care about, and can measure. This combination is good to balance in the process of validation, the ability to produce the reality necessary to conduct engineering and science, but also general observations. A really good confidence builder is the ability of model to produce proper results on things that we care as well as those don’t care about. One of the core issues is the high probability that many of the things we care about in a model cannot be observed, and the model acts as an inference device for science. In this case the observations act to provide confidence that the model’s inferences can be trusted. One of the keys to the whole enterprise is understanding the uncertainty intrinsic to these inferences, and good validation provides essential information for this.

The intrinsic benefit of this approach is a systematic investigation of the ability of the model to produce the features of reality. Ultimately the model needs to produce the features of reality that we care about, and can measure. This combination is good to balance in the process of validation, the ability to produce the reality necessary to conduct engineering and science, but also general observations. A really good confidence builder is the ability of model to produce proper results on things that we care as well as those don’t care about. One of the core issues is the high probability that many of the things we care about in a model cannot be observed, and the model acts as an inference device for science. In this case the observations act to provide confidence that the model’s inferences can be trusted. One of the keys to the whole enterprise is understanding the uncertainty intrinsic to these inferences, and good validation provides essential information for this. One of the greatest issues in validation is “negligible” errors and uncertainties. In many cases these errors are negligible by assertion and no evidence is given. A standing suggestion is that any negligible error or uncertainty be given a numerical value along with evidence for that value. If this cannot be done, the assertion is most likely to be specious, or at least poorly thought through. If you know it is small then you should know how small and why. It is more likely is that it is based on some combination of laziness and wishful thinking. In other cases this practice is an act of negligence, and worse yet it is simply willful ignorance on the part of practitioners. This is an equal opportunity issue for computational modeling and experiments. Often (almost always!) numerical errors are completely ignored in validation. The most brazen violators will simply assert without evidence that the errors are small or the calculated is converged without offering any evidence beyond authority.

One of the greatest issues in validation is “negligible” errors and uncertainties. In many cases these errors are negligible by assertion and no evidence is given. A standing suggestion is that any negligible error or uncertainty be given a numerical value along with evidence for that value. If this cannot be done, the assertion is most likely to be specious, or at least poorly thought through. If you know it is small then you should know how small and why. It is more likely is that it is based on some combination of laziness and wishful thinking. In other cases this practice is an act of negligence, and worse yet it is simply willful ignorance on the part of practitioners. This is an equal opportunity issue for computational modeling and experiments. Often (almost always!) numerical errors are completely ignored in validation. The most brazen violators will simply assert without evidence that the errors are small or the calculated is converged without offering any evidence beyond authority.