Things which matter most must never be at the mercy of things which matter least.

― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

My work day is full of useless bullshit. There is so much bullshit that it has choked out the room for inspiration and value. We are not so much managed as controlled. This control comes from a fundamental distrust of each other to a degree that any independent ideas are viewed as dangerous. This realization has come upon me in the past few years. It has also occurred to me that this could simply be a mid-life crisis manifesting itself, but the evidence might seem to indicate that it is something more significant (look at the bigger picture of the constant crisis my Nation is in). My mid-life attitudes are simply much less tolerant of time-wasting activities with little or no redeeming value. You realize that your time and energy is limited, why waste it on useless things.

My work day is full of useless bullshit. There is so much bullshit that it has choked out the room for inspiration and value. We are not so much managed as controlled. This control comes from a fundamental distrust of each other to a degree that any independent ideas are viewed as dangerous. This realization has come upon me in the past few years. It has also occurred to me that this could simply be a mid-life crisis manifesting itself, but the evidence might seem to indicate that it is something more significant (look at the bigger picture of the constant crisis my Nation is in). My mid-life attitudes are simply much less tolerant of time-wasting activities with little or no redeeming value. You realize that your time and energy is limited, why waste it on useless things.

You and everyone you know are going to be dead soon. And in the short amount of time between here and there, you have a limited amount of fucks to give. Very few, in fact. And if you go around giving a fuck about everything and everyone without conscious thought or choice—well, then you’re going to get fucked.

― Mark Manson

I read a book that had a big impact on my thinking, “The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck” by Mark Manson . In a nutshell, the book says that you have a finite number of fucks to give in life and you should optimize your life by mindfully not giving a fuck about unimportant things. This gives you the time and energy to actually give a fuck about things that actually matter. The book isn’t about not caring, it is about caring about the right things and dismissing the wrong things. What I realized is that increasingly my work isn’t competing for my fucks, they just assume that I will spend my limited fucks on complete bullshit out of duty. It is actually extremely disrespectful of me and my limited time and effort. One conclusion is that the “bosses” (the Lab, the Department of Energy) not give enough of a fuck about me to treat my limited time and energy with respect and make sure my fucks actually matter.

I read a book that had a big impact on my thinking, “The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck” by Mark Manson . In a nutshell, the book says that you have a finite number of fucks to give in life and you should optimize your life by mindfully not giving a fuck about unimportant things. This gives you the time and energy to actually give a fuck about things that actually matter. The book isn’t about not caring, it is about caring about the right things and dismissing the wrong things. What I realized is that increasingly my work isn’t competing for my fucks, they just assume that I will spend my limited fucks on complete bullshit out of duty. It is actually extremely disrespectful of me and my limited time and effort. One conclusion is that the “bosses” (the Lab, the Department of Energy) not give enough of a fuck about me to treat my limited time and energy with respect and make sure my fucks actually matter.

Maturity is what happens when one learns to only give a fuck about what’s truly fuckworthy.

― Mark Manson

I’ve realized recently that a sense of being inspired has departed from work. I’ve felt this building for years with the feeling that my work is useful and important ebbing away. I’ve been blessed for much of my career with work that felt important and useful where an important component of the product was my own added creativity. The work included a distinct element of my own talents and ideas in whatever was produced.

Superficially speaking, the element of inspiration seems to be present, work with meaning and importance with a sense of substantial freedom. As I implied, these elements are superficial, the reality is that each of these pieces has eroded away, and it is useful to explore how this has happened. The job I have would be a dream to most people, but conditions are degrading. It isn’t just my job, but most Americans are experiencing worsening conditions. The exception is the top of the management class, the executives. This is a mirror to broader societal inequalities logically expressed in the working environment. The key is recognizing that my job used to be much better, and that is something worth exploring in some depth.

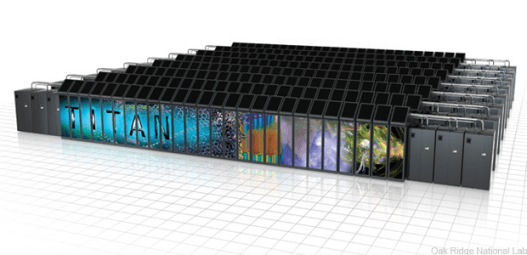

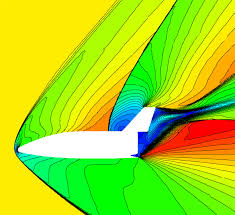

At one level, I should be in the midst of a glorious time to be working in computational science and high-performance computing. We have a massive National program focused on achieving “exascale” or at the very least a great advance in computing power. Looking more closely, we can see deep problems that produce an inspiration gap. On the one hand, we have the technical objectives for the program being obsessively hardware focused for progress. We have been on this hardware path for 25 years producing progress, but no transformation in science has actually occurred (the powers that be will say it has, but the truth is that is hasn’t). Our computations are still not predictive, and the hardware is not the limiting aspect of computational science. Worse yet, the opportunities for massive hardware advances has passed and advancing now is fraught with difficulties, roadblocks and will be immensely costly. Aside from hardware, the program is largely focused on low-level software focused while porting old codes, methods and models (note: the things being ported and not invested in are the actual science!). It is not focused on the more limiting aspects of predictive modeling because they are subtle and risky to work on. They cannot be managed like a construction project using off the shelf management practices better suited for low wage workers, and unsuitable for scientists. The hardware path is superficial, easy to explain to the novice and managed as a project similarly to building a bridge or road.

This gets to the second problem with the current programs, how they are managed. Science cannot be managed like a big construction project, at least not successfully. The result of this management model is a stifling level of micromanagement. Our management model is defined by overwhelming suspicion and lack of trust resulting in massive inefficiency. The reporting requirements for this mode of management are massive and without value except to bean-counters. At the same time, there is no appetite for risk, and no capacity to tolerate failure. As a result, the entire program loses an ability to inspire, or reach for greatness.

If the Apollo Program had been managed in this fashion, we would have never made it to the Moon while spending vastly greater sums of money. If we had managed the Manhattan project in this way, we would have failed to create the atomic bomb. Without risk, there is no reward. There is a huge amount of resource and effort wasted. We do not lack money as much as we lack vision, inspiration and competent management. This is not to say that the United States does not have an issue investing in science and technology, we do. The current level of commitment to science and technology will assure that some other nation becomes the global leader in science and technology. A compounding issue to the lack of investment is how appallingly inefficient our investment is because of how science is managed today. A complimentary compounding element is the lack of trust in the scientists and engineers. Without trust, no one will take any risk and without taking risks nothing great will ever be achieved. If we don’t solve these problems, we will not produce greatness, plain and simple; we will create decline and decay into mediocrity.

But until a person can say deeply and honestly, “I am what I am today because of the choices I made yesterday,” that person cannot say, “I choose otherwise.

― Stephen R. Covey

None of these problems suddenly appeared. They are the consequence of decades of evolution toward the current completely dysfunctional management approach. Once great Laboratories have been brought to heel with a combination of constraints, regulations and money. There is more than enough money and people to accomplish massive things. The problem is that the constraints and regulatory environment have destroyed any chance for achievement. With each passing year our scientific programs sound more expansive, but less capable of achieving anything of substance. Our management approach is undermining achievement at every turn. The focus of the management is not producing results, but producing the appearance of success without regard for reality. The workforce must be complaint, and never make any mistakes. The best way to avoid mistakes is low-balling results. You always aim low to avoid the possibility of failing. Each year we aim a little lower, and achieve a little less. This has produced a steady erosion of capability much like an interest-bearing account, but in reverse.

If we look at work, it might seem that an inspired workforce would be a benefit worth creating. People would work hard and create wonderful things because of the depth of their commitment to a deeper purpose. An employer would benefit mightily from such an environment, and the employees could flourish brimming with satisfaction and growth. With all these benefits, we should expect the workplace to naturally create the conditions for inspiration. Yet this is not happening; the conditions are the complete opposite. The reason is that inspired employees are not entirely controlled. Creative people do things that are unexpected and unplanned. The job of managing a work place like this is much harder. In addition, mistakes and bad things happen too. Failure and mistakes are an inevitable consequence of hard working inspired people. This is the thing that our work places cannot tolerate. The lack of control and unintended consequences are unacceptable. Fundamentally this stems from a complete lack of trust. Our employers do not trust their employees at all. In turn, the employees do not trust the workplace. It is vicious cycles that drags inspiration under and smothers it. The entire environment is overflowing with micromanagement, control suspicion and doubt.

If we look at work, it might seem that an inspired workforce would be a benefit worth creating. People would work hard and create wonderful things because of the depth of their commitment to a deeper purpose. An employer would benefit mightily from such an environment, and the employees could flourish brimming with satisfaction and growth. With all these benefits, we should expect the workplace to naturally create the conditions for inspiration. Yet this is not happening; the conditions are the complete opposite. The reason is that inspired employees are not entirely controlled. Creative people do things that are unexpected and unplanned. The job of managing a work place like this is much harder. In addition, mistakes and bad things happen too. Failure and mistakes are an inevitable consequence of hard working inspired people. This is the thing that our work places cannot tolerate. The lack of control and unintended consequences are unacceptable. Fundamentally this stems from a complete lack of trust. Our employers do not trust their employees at all. In turn, the employees do not trust the workplace. It is vicious cycles that drags inspiration under and smothers it. The entire environment is overflowing with micromanagement, control suspicion and doubt.

In the end that was the choice you made, and it doesn’t matter how hard it was to make it. It matters that you did.”

― Cassandra Clare

How do we change it?

One clear way of changing this is giving the employees more control over their work. It has become very clear to me that we have little or no power to make choices at work. One of the clearest ways of making a choice is being given the option to say “NO”. Many articles are written about the power of saying NO to things because it makes your “YES” more powerful. The problem is that we can’t say NO to so many things. I can’t begin to elaborate on all the functionally useless things that don’t have to option of skipping. I spend a great deal of effort on mandatory meetings, training, and reporting that has no value whatsoever. None of it is optional, and most of it is completely useless. Each of these useless activities drains away energy from something useful. All of the useless things I do are related to a deep lack of trust in me and my fellow scientists.

Let’s take the endless reporting and tracking of work as a key example. There is nothing wrong with planning a project and getting updates on progress. This is not what is happening today. We are seeing a system that does not trust its employees and needs to continually look over their sholders. A big part of the problem is that the employees are completely uninspired because the programs they work on are terrible. The people see very little of themselves in the work, or much purpose and meaning in the work. Rather than make the work something deeper and more collaborative, the employers increase the micromanagement and control. A big part of the lack of trust is the reporting. Somehow the whole concept of quarterly progress used for business has become part of science creating immense damage. Lately quarterly progress isn’t enough, and we’ve moved to monthly reporting. All of this says, “we don’t trust you,” “we need to watch you closely” and “don’t fuck up”.

The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum….

― Noam Chomsky

If we can’t say NO to all this useless stuff, we can’t say YES to things either. My work and time budget is completely stocked up with non-optional things that I should say NO to. They are largely useless and produce no value. Because I can’t say NO, I can’t say YES to something better. My employer is sending a message to me with very clear emphasis, we don’t trust you to make decisions. Your ideas are not worth working on. You are expected to implement other people’s ideas no matter how bad they are. You have no ability to steer the ideas to be better. Your expertise has absolutely no value. A huge part of this problem is the ascendency of the management class as the core of organizational value. We are living in the era of the manager; the employee is a cog and not valued. Organizations voice platitudes toward the employees, but they are hollow. The actions of the organization spell out their true intent. Employees are not to be trusted, they are to be controlled and they need to do what they are told to do. Inspired employees would do things that are not intended, and take organizations in new directions, focused on new things. This would mean losing control and changing plans. More importantly, the value of the organization would move away from the managers and move to the employees. Managers are much happier with employees that are “seen and not heard”.

If we can’t say NO to all this useless stuff, we can’t say YES to things either. My work and time budget is completely stocked up with non-optional things that I should say NO to. They are largely useless and produce no value. Because I can’t say NO, I can’t say YES to something better. My employer is sending a message to me with very clear emphasis, we don’t trust you to make decisions. Your ideas are not worth working on. You are expected to implement other people’s ideas no matter how bad they are. You have no ability to steer the ideas to be better. Your expertise has absolutely no value. A huge part of this problem is the ascendency of the management class as the core of organizational value. We are living in the era of the manager; the employee is a cog and not valued. Organizations voice platitudes toward the employees, but they are hollow. The actions of the organization spell out their true intent. Employees are not to be trusted, they are to be controlled and they need to do what they are told to do. Inspired employees would do things that are not intended, and take organizations in new directions, focused on new things. This would mean losing control and changing plans. More importantly, the value of the organization would move away from the managers and move to the employees. Managers are much happier with employees that are “seen and not heard”.

If something is not a “hell, YEAH!”, then it’s a “no!

― James Altucher

What should I be saying YES to?

If I could say YES then I might be able to put my focus into useful, inspired and risky endeavors. I could produce work that might go in directions that I can’t anticipate or predict. These risky ideas might be complete failures. Being a failure I could learn invaluable lessons, and grow my knowledge and expertise. Being risky these ideas might produce something amazing and create something of real value. None of these outcomes are a sure thing. All of these characteristics are unthinkable today. Our managers want a sure thing and cannot deal with unpredictable outcomes. The biggest thing our managers cannot tolerate is failure. Failure is impossible to take and leads to career limiting consequences. For this reason, inspired risks are impossible to support. As a result, I can’t say NO to anything, no matter how stupid and useless it is. In the process, I see work as an increasingly frustrating waste of my time.

Action expresses priorities.

― Mahatma Gandhi

We all have limits defined our personal time and effort. Naturally we have 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and 365 days a year, along with our own personal energy budget. If we are managed well, we can expand our abilities and create more. We can be more efficient and work more effectively. If one looks honestly at how we are managed expanding our abilities and personal growth has almost no priority. Creating an inspiring and exciting place to work is equally low on the list. Given the pathetic level of support for creation and inspiration attention naturally turns elsewhere. Everyone needs a level of balance in their lives and we obviously gravitate toward places where a difference can be made.

As Mark Manson writes we only have so many fucks to give and my work is doing precious little to give them there. I have always focused on personal growth and increasingly personal growth is resisted by work instead of resonated with. It has become quite obvious that being the best “me” is not remotely a priority. The priority at work is to be compliant, take no risks, fail at nothing and help produce marketing material for success and achievement. We aren’t doing great work anymore, but pretend we are. My work could simply be awesome, but that would require giving me the freedom to set priorities, take risks, fail often, learn continually and actually produce wonderful things. If this happened the results would speak for themselves and the marketing would take care of itself. When the Labs I’ve worked at were actually great this is how it actually happened. The Labs were great because they achieved great things. The labs said NO to a lot of things, so they could say YES to the right things. Today, we simply don’t have this freedom.

As Mark Manson writes we only have so many fucks to give and my work is doing precious little to give them there. I have always focused on personal growth and increasingly personal growth is resisted by work instead of resonated with. It has become quite obvious that being the best “me” is not remotely a priority. The priority at work is to be compliant, take no risks, fail at nothing and help produce marketing material for success and achievement. We aren’t doing great work anymore, but pretend we are. My work could simply be awesome, but that would require giving me the freedom to set priorities, take risks, fail often, learn continually and actually produce wonderful things. If this happened the results would speak for themselves and the marketing would take care of itself. When the Labs I’ve worked at were actually great this is how it actually happened. The Labs were great because they achieved great things. The labs said NO to a lot of things, so they could say YES to the right things. Today, we simply don’t have this freedom.

We are our choices.

― Jean-Paul Sartre

If we could say NO to the bullshit, and give our limited fucks a powerful YES, we might be able to achieve great things. Our Labs could stop trying to convince everyone that they were doing great things and actually do great things. The missing element at work today is trust. If the trust was there we could produce inspiring work that would generate genuine pride and accomplishment. Computing is a wonderful example of these principles in action. Scientific computing became a force in science and engineering contributing to genuine endeavors for massive societal goals. Computing helped win the Cold War and put a man on the moon. Weather and climate has been modeled successfully. More broadly, computers have reshaped business and now societally massively. All of these endeavors had computing contributing to solutions. Computing focused on computers was not the endeavor itself like it is today. The modern computing emphasis was originally part of a bigger program of using science to support the nuclear stockpile without testing. It was part of a focused scientific enterprise and objective. Today it is a goal unto itself, and not moored to anything larger. If we want to progress and advance science, we should focus on great things for society, not superficially put our effort into mere tools.

If we could say NO to the bullshit, and give our limited fucks a powerful YES, we might be able to achieve great things. Our Labs could stop trying to convince everyone that they were doing great things and actually do great things. The missing element at work today is trust. If the trust was there we could produce inspiring work that would generate genuine pride and accomplishment. Computing is a wonderful example of these principles in action. Scientific computing became a force in science and engineering contributing to genuine endeavors for massive societal goals. Computing helped win the Cold War and put a man on the moon. Weather and climate has been modeled successfully. More broadly, computers have reshaped business and now societally massively. All of these endeavors had computing contributing to solutions. Computing focused on computers was not the endeavor itself like it is today. The modern computing emphasis was originally part of a bigger program of using science to support the nuclear stockpile without testing. It was part of a focused scientific enterprise and objective. Today it is a goal unto itself, and not moored to anything larger. If we want to progress and advance science, we should focus on great things for society, not superficially put our effort into mere tools.

Most of us spend too much time on what is urgent and not enough time on what is important.

― Stephen R. Covey

Say no to everything, so you can say yes to the one thing.

― Richie Norton

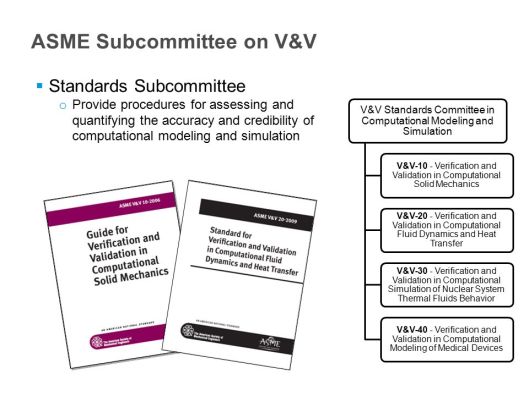

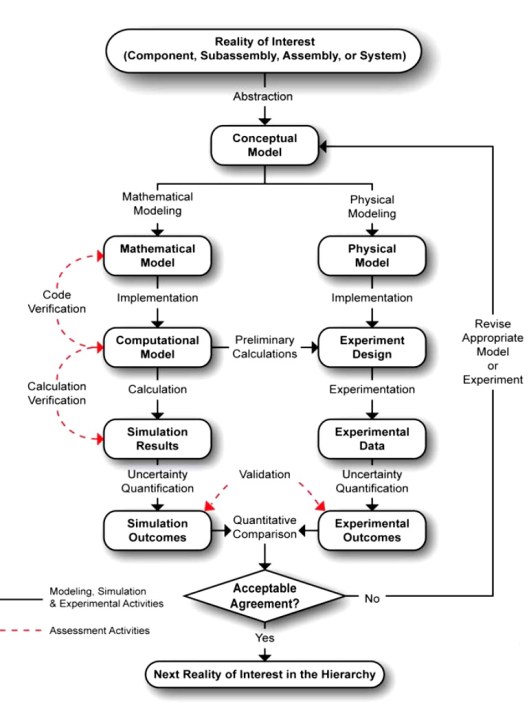

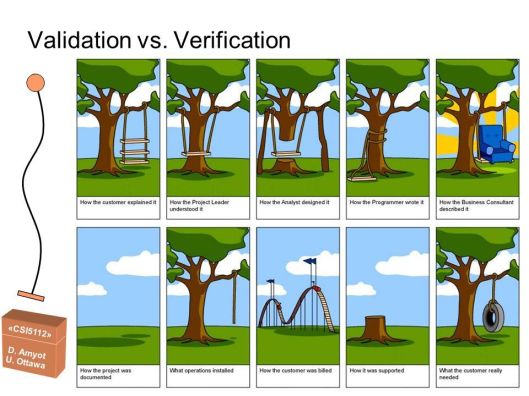

In the conduct of predictive science, we should look to uncertainty as one of our primary outcomes. When V&V is conducted with high professional standards, uncertainty is unveiled and estimated in magnitude. With our highly over-promised mantra of predictive modeling enabled by high performance computing, uncertainty is almost always viewed negatively. This creates an environment where willful or casual ignorance of uncertainty is tolerated and even encouraged. Incomplete and haphazard V&V practice becomes accepted because it serves the narrative of predictive science. The truth and actual uncertainty is treated as bad news, and greeted with scorn instead of praise. It is simply so much easier to accept the comfort that the modeling has achieved a level of mastery. This comfort is usually offered without evidence.

In the conduct of predictive science, we should look to uncertainty as one of our primary outcomes. When V&V is conducted with high professional standards, uncertainty is unveiled and estimated in magnitude. With our highly over-promised mantra of predictive modeling enabled by high performance computing, uncertainty is almost always viewed negatively. This creates an environment where willful or casual ignorance of uncertainty is tolerated and even encouraged. Incomplete and haphazard V&V practice becomes accepted because it serves the narrative of predictive science. The truth and actual uncertainty is treated as bad news, and greeted with scorn instead of praise. It is simply so much easier to accept the comfort that the modeling has achieved a level of mastery. This comfort is usually offered without evidence. This last point gets at the problems with implementing a more professional V&V practice. If V&V finds that uncertainties are too large, the rational choice may be to not use modeling at all. This runs the risk of being politically incorrect. Programs are sold on predictive modeling, and the money might look like a waste! We might find that the uncertainties from numerical error are much smaller than other uncertainties, and the new super expensive, super-fast computer will not help make things any better. In other cases, we might find out that the model is not converging toward a (correct) solution. Again, the computer is not going to help. Actual V&V is likely to produce results that require changing programs and investments in reaction. Current management often looks to this as a negative and worries that the feedback will reflect poorly on previous investments. There is a deep-seated lack of trust between the source of the money and the work. The lack of trust is driving a lack of honesty in science. Any money spent on fruitless endeavors is viewed as a potential scandal. The money will simply be withdrawn instead of redirected more productively. No one trusts the scientific process to work effectively. The result is an unwillingness to engage in a frank and accurate dialog about how predictive we actually are.

This last point gets at the problems with implementing a more professional V&V practice. If V&V finds that uncertainties are too large, the rational choice may be to not use modeling at all. This runs the risk of being politically incorrect. Programs are sold on predictive modeling, and the money might look like a waste! We might find that the uncertainties from numerical error are much smaller than other uncertainties, and the new super expensive, super-fast computer will not help make things any better. In other cases, we might find out that the model is not converging toward a (correct) solution. Again, the computer is not going to help. Actual V&V is likely to produce results that require changing programs and investments in reaction. Current management often looks to this as a negative and worries that the feedback will reflect poorly on previous investments. There is a deep-seated lack of trust between the source of the money and the work. The lack of trust is driving a lack of honesty in science. Any money spent on fruitless endeavors is viewed as a potential scandal. The money will simply be withdrawn instead of redirected more productively. No one trusts the scientific process to work effectively. The result is an unwillingness to engage in a frank and accurate dialog about how predictive we actually are.

There is something seriously off about working on scientific computing today. Once upon a time it felt like working in the future where the technology and the work was amazingly advanced and forward-looking. Over the past decade this feeling has changed dramatically. Working in scientific computing is starting to feel worn-out, old and backwards. It has lost a lot of its sheen and it’s no longer sexy and fresh. If I look back 10 years everything we then had was top of the line and right at the “bleeding” edge. Now we seem to be living in the past, the current advances driving computing are absent from our work lives. We are slaving away in a totally reactive mode. Scientific computing is staid, immobile and static, where modern computing is dynamic, mobile and adaptive. If I want to step into the modern world, now I have to leave work. Work is a glimpse into the past instead of a window to the future. It is not simply the technology, but the management systems that come along with our approach. We are being left behind, and our leadership seems oblivious to the problem.

There is something seriously off about working on scientific computing today. Once upon a time it felt like working in the future where the technology and the work was amazingly advanced and forward-looking. Over the past decade this feeling has changed dramatically. Working in scientific computing is starting to feel worn-out, old and backwards. It has lost a lot of its sheen and it’s no longer sexy and fresh. If I look back 10 years everything we then had was top of the line and right at the “bleeding” edge. Now we seem to be living in the past, the current advances driving computing are absent from our work lives. We are slaving away in a totally reactive mode. Scientific computing is staid, immobile and static, where modern computing is dynamic, mobile and adaptive. If I want to step into the modern world, now I have to leave work. Work is a glimpse into the past instead of a window to the future. It is not simply the technology, but the management systems that come along with our approach. We are being left behind, and our leadership seems oblivious to the problem. Even worse than the irony is the price this approach is exacting on scientific computing. For example, the computing industry used to beat a path to scientific computing’s door, and now we have to basically bribe the industry to pay attention to us. A fair accounting of the role of government in computing is some combination of being a purely niche market, and partially pork barrel spending. Scientific computing used to be a driving force in the industry, and now lies as a cul-de-sac, or even pocket universe, divorced from the day-to-day reality of computing. Scientific computing is now a tiny and unimportant market to an industry that dominates the modern World. In the process, scientific computing has allowed itself to become disconnected from modernity, and hopelessly imbalanced. Rather than leverage the modern World and its technological wonders many of which are grounded in information science, it resists and fails to make best use of the opportunity. It robs scientific computing of impact in the broader World, and diminishes the draw of new talent to the field.

Even worse than the irony is the price this approach is exacting on scientific computing. For example, the computing industry used to beat a path to scientific computing’s door, and now we have to basically bribe the industry to pay attention to us. A fair accounting of the role of government in computing is some combination of being a purely niche market, and partially pork barrel spending. Scientific computing used to be a driving force in the industry, and now lies as a cul-de-sac, or even pocket universe, divorced from the day-to-day reality of computing. Scientific computing is now a tiny and unimportant market to an industry that dominates the modern World. In the process, scientific computing has allowed itself to become disconnected from modernity, and hopelessly imbalanced. Rather than leverage the modern World and its technological wonders many of which are grounded in information science, it resists and fails to make best use of the opportunity. It robs scientific computing of impact in the broader World, and diminishes the draw of new talent to the field. present imbalances. If one looks at the modern computing industry and its ascension to the top of the economic food chain, two things come to mind: mobile computing – cell phones – and the Internet. Mobile computing made connectivity and access ubiquitous with massive penetration into our lives. Networks and apps began to create new social connections in the real world and lubricated communications between people in a myriad of ways. The Internet became both a huge information repository, and commerce. but also an engine of social connection. In short order, the adoption and use of the internet and computing in the broader human World overtook and surpassed the use by scientists and business. Where once scientists used and knew computers better than anyone, now the World is full of people for whom computing is far more important than for science. Science once were in the lead, and now they are behind. Worse yet, science is not adapting to this new reality.

present imbalances. If one looks at the modern computing industry and its ascension to the top of the economic food chain, two things come to mind: mobile computing – cell phones – and the Internet. Mobile computing made connectivity and access ubiquitous with massive penetration into our lives. Networks and apps began to create new social connections in the real world and lubricated communications between people in a myriad of ways. The Internet became both a huge information repository, and commerce. but also an engine of social connection. In short order, the adoption and use of the internet and computing in the broader human World overtook and surpassed the use by scientists and business. Where once scientists used and knew computers better than anyone, now the World is full of people for whom computing is far more important than for science. Science once were in the lead, and now they are behind. Worse yet, science is not adapting to this new reality.

that Google solved is firmly grounded in scientific computing and applied mathematics. It is easy to see how massive the impact of this solution is. Today we in scientific computing are getting further and further from relevance to society. This niche does scientific computing little good because it is swimming against a tide that is more like a tsunami. The result is a horribly expensive and marginally effective effort that will fail needlessly where it has the potential to provide phenomenal value.

that Google solved is firmly grounded in scientific computing and applied mathematics. It is easy to see how massive the impact of this solution is. Today we in scientific computing are getting further and further from relevance to society. This niche does scientific computing little good because it is swimming against a tide that is more like a tsunami. The result is a horribly expensive and marginally effective effort that will fail needlessly where it has the potential to provide phenomenal value.

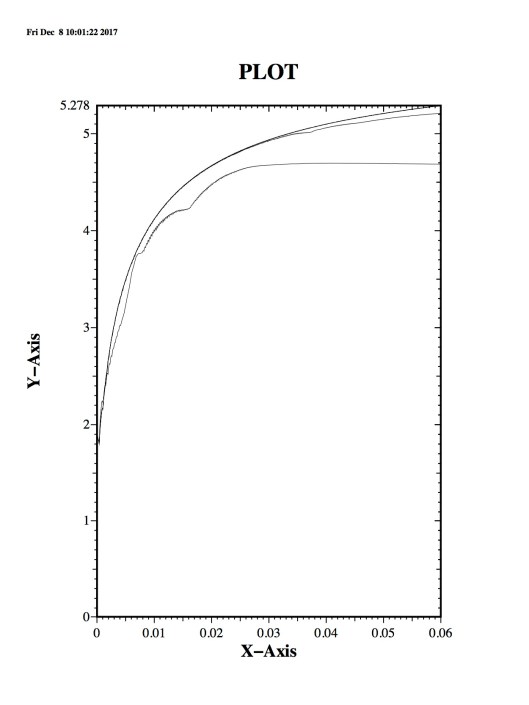

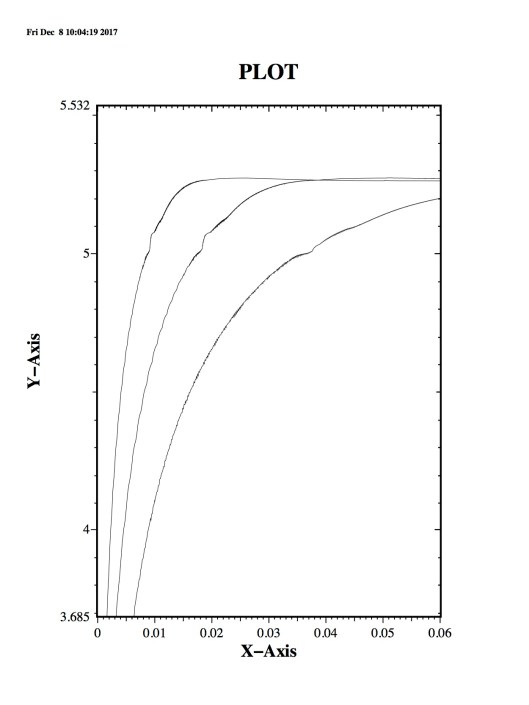

Ideally, it should not be, but proving that ideal is a very high bar that is almost never met. A great deal of compelling evidence is needed to support an assertion that the code is not part of the model. The real difficulty is that the more complex the modeling problem is, the more the code is definitely and irreducibly part of the model. These complex models are the most important uses of modeling and simulation. The complex models of engineered things, or important physical systems have many submodels each essential to successful modeling. The code is often designed quite specifically to model a class of problems. The code then becomes are clear part of the definition of the problem. Even in the simplest cases, the code includes the recipe for the numerical solution of a model. This numerical solution leaves its fingerprints all over the solution of the model. The numerical solution is imperfect and contains errors that influence the solution. For a code, there is the mesh and geometric description plus boundary conditions, not to mention the various modeling options employed. Removing the specific details of the implementation of the model in the code from consideration as part of the model becomes increasingly intractable.

Ideally, it should not be, but proving that ideal is a very high bar that is almost never met. A great deal of compelling evidence is needed to support an assertion that the code is not part of the model. The real difficulty is that the more complex the modeling problem is, the more the code is definitely and irreducibly part of the model. These complex models are the most important uses of modeling and simulation. The complex models of engineered things, or important physical systems have many submodels each essential to successful modeling. The code is often designed quite specifically to model a class of problems. The code then becomes are clear part of the definition of the problem. Even in the simplest cases, the code includes the recipe for the numerical solution of a model. This numerical solution leaves its fingerprints all over the solution of the model. The numerical solution is imperfect and contains errors that influence the solution. For a code, there is the mesh and geometric description plus boundary conditions, not to mention the various modeling options employed. Removing the specific details of the implementation of the model in the code from consideration as part of the model becomes increasingly intractable. central to the conduct of science and engineering that it should be dealt with head on. It isn’t going away. We model our reality when we want to make sure we understand it. We engage in modeling when we have something in the Real World, we want to demonstrate an understand of. Sometimes this is for the purpose of understanding, but ultimately this gives way to manipulation, the essence of engineering. The Real World is complex and effective models are usually immune to analytical solution.

central to the conduct of science and engineering that it should be dealt with head on. It isn’t going away. We model our reality when we want to make sure we understand it. We engage in modeling when we have something in the Real World, we want to demonstrate an understand of. Sometimes this is for the purpose of understanding, but ultimately this gives way to manipulation, the essence of engineering. The Real World is complex and effective models are usually immune to analytical solution. are implemented in computer code, or “a computer code”. The details and correctness of the implementation become inseparable from the model itself. It becomes quite difficult to extract the model as any sort of pure mathematical construct; the code is part of it intimately.

are implemented in computer code, or “a computer code”. The details and correctness of the implementation become inseparable from the model itself. It becomes quite difficult to extract the model as any sort of pure mathematical construct; the code is part of it intimately. k requiring detailed verification and validation. It is an abstraction and representation of the processes we believe produce observable physical effects. We theorize that the model explains how these effects are produced. Some models are not remotely this high minded; they are nothing, but crude empirical engines for reproducing what we observe. Unfortunately, as phenomena become more complex, these crude models become increasingly essential to modeling. They may not play a central role in the modeling, but still provide necessary physical effects for utility. These submodels necessary to produce realistic simulations become ever more prone to include these crude empirical engines as problems enter the engineering realm. As the reality of interest becomes more complicated, the modeling becomes elaborate and complex being a deep chain of efforts to grapple with these details.

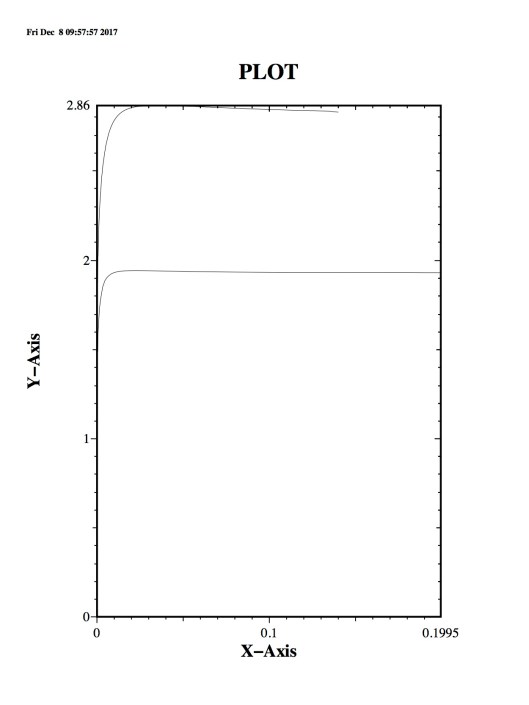

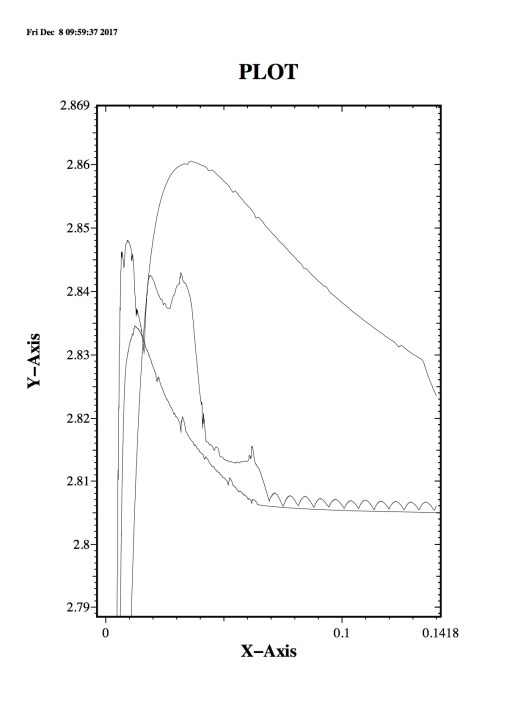

k requiring detailed verification and validation. It is an abstraction and representation of the processes we believe produce observable physical effects. We theorize that the model explains how these effects are produced. Some models are not remotely this high minded; they are nothing, but crude empirical engines for reproducing what we observe. Unfortunately, as phenomena become more complex, these crude models become increasingly essential to modeling. They may not play a central role in the modeling, but still provide necessary physical effects for utility. These submodels necessary to produce realistic simulations become ever more prone to include these crude empirical engines as problems enter the engineering realm. As the reality of interest becomes more complicated, the modeling becomes elaborate and complex being a deep chain of efforts to grapple with these details. impact of numerical approximation. The numerical uncertainty needs to be accounted for to isolate the model. This uncertainty defines the level of approximation in the solution to the model, and a deviation from the mathematical idealization the model represents. In actual validation work, we see a stunning lack of this essential step from validation work presented. Another big part of the validation is recognizing the subtle differences between calibrated results and predictive simulation. Again, calibration is rarely elaborated in validation to the degree that it should.

impact of numerical approximation. The numerical uncertainty needs to be accounted for to isolate the model. This uncertainty defines the level of approximation in the solution to the model, and a deviation from the mathematical idealization the model represents. In actual validation work, we see a stunning lack of this essential step from validation work presented. Another big part of the validation is recognizing the subtle differences between calibrated results and predictive simulation. Again, calibration is rarely elaborated in validation to the degree that it should.

strong function of the discretization and solver used in the code. The question of whether the code matters comes down to asking if another code used skillfully would produce a significantly different result. This is rarely, if ever, the case. To make matters worse, verification evidence tends to be flimsy and half-assed. Even if we could make this call and ignore the code, we rarely have evidence that this is a valid and defensible decision.

strong function of the discretization and solver used in the code. The question of whether the code matters comes down to asking if another code used skillfully would produce a significantly different result. This is rarely, if ever, the case. To make matters worse, verification evidence tends to be flimsy and half-assed. Even if we could make this call and ignore the code, we rarely have evidence that this is a valid and defensible decision.