If we do not trust one another, we are already defeated.

Most mornings I walk our dog, Duke, at a park near my house. The park is next to an elementary school. Here, I see direct evidence of how little trust Americans have in each other. I see the kids walking to school and if they are walking it is with parents. You even see parents with kids at bustops within eye shot of the house. You never see a kid walking alone to school. In fact this seems to be unthinkable today. If I think about myself all I remember is walking myself to school or later walking with my brother. Usually I would walk with friends the small distance to school.

The significant change is in social and societal trust. We no longer believe that children walking to school are safe. We fear all sorts of terrible things happening to them, many of which are figments of people’s imaginations and highly unlikely dangers. It’s instructive to compare the period from 1968 to 1976, when I walked to school, to the present day,when no one allows their child to walk to school. Regardless, this is a concerning sign for the health of our nation.Ultimately, we can’t avoid the fact that bad things happen and are inevitable (shit happens!). They aren’t blameworthy, but without trust,blame is readily assigned. Without trust people play it safe to avoid the blame.

“We are all mistaken sometimes; sometimes we do wrong things, things that have bad consequences. But it does not mean we are evil, or that we cannot be trusted ever afterward.”

― Alison Croggon

If you look at the United States today you see a nation where no one trusts each other. The impacts from this lack of trust are broad. It is important to look at what trust allows and its lack prohibits. Not trusting is expensive and it limits success. Those costs and impacts are hurting Americans left and right. I see it play out in my life. If we look around this damage is everywhere. It is evident in the politics today. It is evident in our personal lives too.

Fear is driving this change in behavior. Parents are terrified of sexual predators and random violence harming their children, despite the incredibly low probability of such events occurring. This reflects a common aspect of our low-trust society: we manage low-probability events at great cost. This phenomenon is widespread throughout society, as we incur enormous expenses to mitigate minuscule risks. In the case of children, this is ruining childhood. Socially, we see loneliness and isolation. For society as a whole, building or creating anything new becomes difficult and expensive.Everything costs more and takes longer due to the lack of trust.

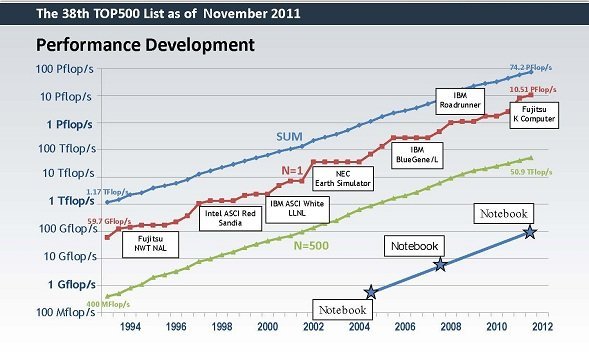

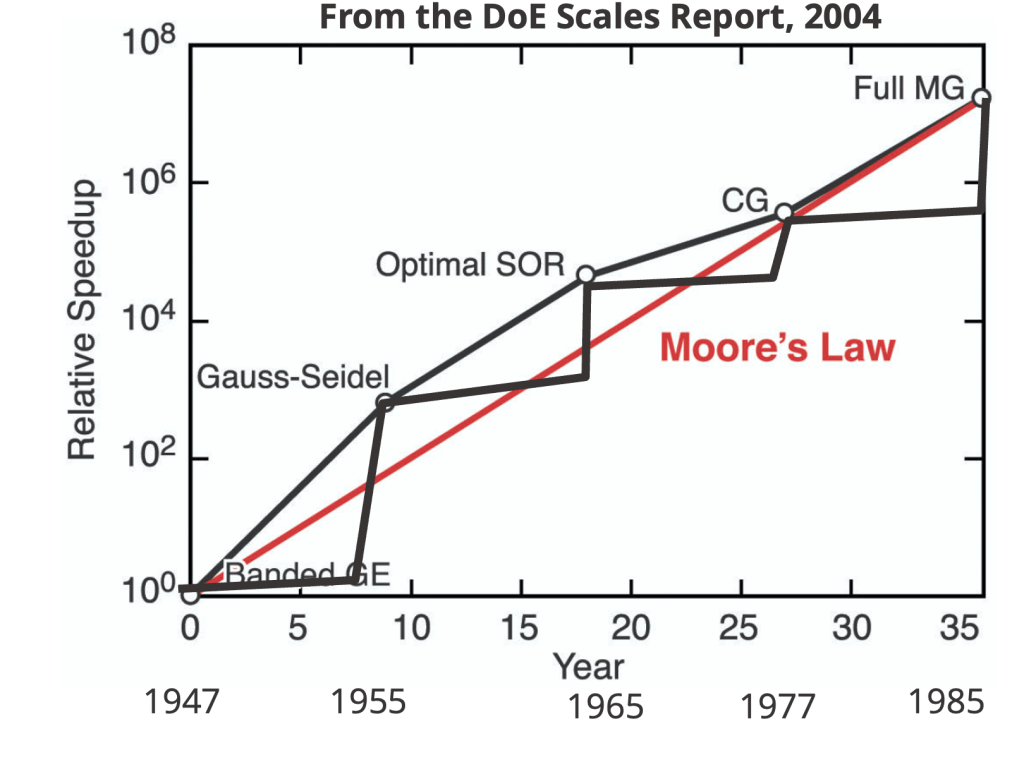

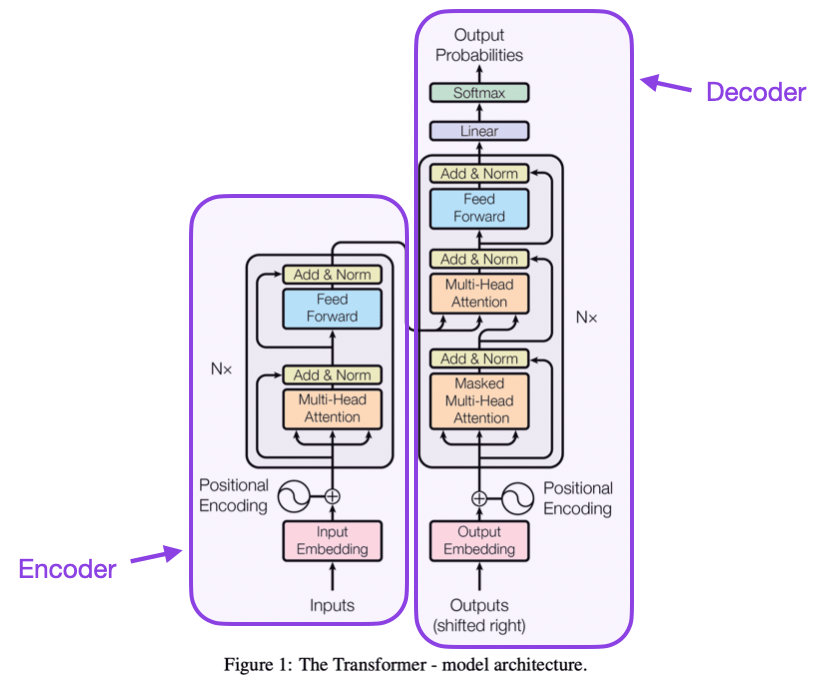

I thoroughly enjoyed writing about a technical topic. It was both enjoyable and fulfilling, like cooking a delicious meal that you enjoy eating and even better when someone else appreciates it. However, there’s an underlying issue that’s been playing out behind the scenes. While there’s a clear benefit to conducting risky research, something is hindering progress.Ultimately, the reason for not realizing the benefits of risky research is a lack of trust. Risky research requires failure, and lots of it. Without trust, failure becomes unacceptable and suspicious. Without trust, people become cautious, and caution hinders progress. Caution leads to stagnation and decline, which is precisely what we observe across the country

“Trust is the glue of life. It’s the most essential ingredient in effective communication. It’s the foundational principle that holds all relationships.”

― Stephen R. Covey

Trust is best understood within our most intimate and important personal relationships. Whether it’s a romantic partner or friend, trust is foundational. When trust is lost in these relationships, they are at risk. If trust is not repaired, it can lead to the end of the relationship. Studies have shown that trust is built through several essential behaviors.

The first is authenticity, which involves presenting yourself as your true self. Faking your personality has the opposite effect and fosters suspicion. The second aspect is competence in areas relevant to the relationship. This could be athletic ability or intellectual prowess. Finally, trust requires demonstrated empathy, a deep care and concern for the well-being of others. The person you trust will understand your feelings and care about your welfare.

“Trust is the glue of life. It’s the most essential ingredient in effective communication. It’s the foundational principle that holds all relationships.”

― Stephen R. Covey

Stephen Covey’s The Speed of Trust provides valuable insights into the benefits of trust. The book demonstrates how trust can enhance efficiency and productivity. When trust exists, remarkable achievements are possible. Trust is contagious; when we are trusted, we trust others. Trust enables individuals to perform at their best, and organizations to achieve their highest potential. Conversely, a lack of trust is slow and costly. It is destructive. When we don’t trust, we tend to make mistakes and hinder progress. Lack of trust is the root of many fuck-ups.

The leaders who work most effectively, it seems to me, never say ‘I.’ And that’s not because they have trained themselves not to say ‘I.’ They don’t think ‘I.’ They think ‘we’; they think ‘team.’ …. This is what creates trust, what enables you to get the task done.

The decline in American trust can be traced back to the 1970s. Several events shattered the spell of trust that had held the United States since the end of World War II. The upheavals of the 1960s had begun to erode trust with a generational divide, the civil rights movement, and a misguided war. The Nixon administration’s criminal actions exposed corruption at the highest levels of government. Nixon prioritized his own interests and power, seeking revenge against the culture he disliked. While Nixon’s religiosity may have distinguished him from Trump, it nonetheless reflects a decline in trust.

Other factors contributed to the unraveling of trust in the United States. The mid-1970s marked a peak in economic equality. Americans could comfortably achieve middle-class status with a single blue-collar income. People across the nation enjoyed a more level playing field, fostering empathy and trust. This shared experience and common culture allowed for authenticity to flourish. The nation was thriving and a global economic powerhouse, demonstrating competence. However, the energy crisis of the mid-1970s challenged these elements. The economy suffered, and blue-collar industries took a hit, further eroding trust.

“Never trust anyone, Daniel, especially the people you admire. Those are the ones who will make you suffer the worst blows.”

― Carlos Ruiz Zafón

The 1980s introduced new factors that undermined these trust drivers. The Reagan Revolution, characterized by a focus on business success through tax cuts and legal changes, significantly increased corporate wealth and power. The simultaneous assault on labor further weakened the ability of blue-collar jobs to provide a comfortable living. This marked the beginning of a widening economic inequality in the United States, which continues to grow today. This inequality erodes all aspects of societal and social trust, as people now live vastly different lives and hold radically different views of success. Consequently, people struggle to understand one another. This lack of understanding undermines empathy and destroys trust.

Other societal developments have accelerated the loss of trust. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 led to a decline in trust and a rise in fear. The fear-based responses and societal changes that followed have persisted. Instead of progress toward a more inclusive society, division and bigotry are on the rise. The internet and the attention-driven economy have further exacerbated these trends. The cumulative effect of these factors is a massive political and cultural divide. The lack of trust now extends to the political system, threatening democracy itself and potentially spiraling further into an abyss.

“I’m not upset that you lied to me, I’m upset that from now on I can’t believe you.”

― Friedrich Nietzsche

Trust is cultivated through countless small acts. It was top of mind this past week and repeatedly demonstrated to me. I clearly distinguished between what was said privately and publicly. This inconsistency was painful to experience and significantly damaged trust in an important relationship. At work, I observe technical accuracy and competence being overshadowed by expediency. People hesitate to engage openly on topics due to fear of retaliation. All of this stems from and exacerbates a lack of trust

Building and fostering trust is paramount in all these situations. Trust in our relationships, with our coworkers, and among our fellow citizens is essential. With trust, things will improve, but it requires courage and effort. Trust is a product of strong character. It unleashes competence and grows alongside it. Trust is efficient and the foundation of success. We need leadership that guides us toward trust and away from fear and suspicion. This involves identifying the factors that have eroded trust and changing course. Many people benefit from these trust-destroying elements. To achieve trust, society needs to become more equitable with a deeper shared culture. We need a spirit that recognizes a future where trust prevails. Living, relating, and working in a place of trust is a more positive experience

Trust is the highest form of human motivation. It brings out the very best in people.

– Stephen Covey