tl;dr.

The practice of code verification has focused on finding bugs in codes. This is grounded in the proving that a code is correctly implementing a method. While this is useful and important, it does not inspire. Code verification can be used for far more. It can be the partner to method development and validation or application assessment. It can also provide expectations for code behavior and mesh requirements on applications. Together these steps can make code verification more relevant and inspiring. It can connect it to important scientific and engineering work pulling it away from computer science.

When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it.

– Lord Kelvin

My Connection to Code Verification

Writing about code verification might seem like a scheme to reduce my already barren readership. All kidding aside, code verification is not the most compelling topic for most. This includes people making their living writing computational solvers. For me it is a topic of much greater gravity. While I am inspired by the topic, most people are not. The objective here is to widen its scope and importance. Critically, I have noticed the problems getting worse as code verification seems to fade from serious attention. This all points to a need for me to think about this topic deeply. It is time to consider a change to how code verification is talked about.

“If you can not measure it, you can not improve it.”

– Lord Kelvin

My starting point for thinking about code verification is to look at myself. Code verification is something I’ve been doing for more than 30 years. I did it before I knew it was called “code verification.” Originally, I did it to assist my development of improved methods in codes I worked on. I also used it to assure that my code was correct, but this was secondary. This work utilized test problems to measure the correctness and more importantly the quality of methods. As I continued to mature and grow in my scientific career I sought to enhance my craft. The key aspect of growth was utilizing verification to exactly measure method character and quality. It was through verification that I understood if a method passed muster.

“If failure is not an option, then neither is success.”

― Seth Godin

Eventually, I developed new problems to more acutely measure methods. I also developed problems to break methods and codes. When you break a method you help define its limitations. Over time I saw the power of code verification as I practiced it. This contrasted to how it was described by V&V experts. The huge advantage and utility of code verification I found in method development was absent. Code verification was relegated to correctness through code bug detection. In this mode code verification is a spectator to the real work of science. I know it can be so very much more.

“I have been struck again and again by how important measurement is to improving the human condition.”

– Bill Gates

The Problem with Code Verification

In the past year I’ve reviewed many different proposals in computational science. Almost all of them should be utilizing code verification integrally in their work. Almost all of them failed to do so. At best, code verification is given lip service because of proposal expectations. At worst it is completely ignored. The reason is that code verification does not set itself as a serious activity for scientific work. It is viewed as a trivial activity beneath mention in a research proposal. The fault lies with the V&V community’s narrative about it. (I’ve written before on the topic generally https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2024/08/14/algorithms-are-the-best-way-to-improve-computing-power/)

“Program testing can be used to show the presence of bugs, but never to show their absence!”

― Edsger W. Dijkstra

Let’s take a look at the narrative chosen for code verification more closely. Code verification is discussed primarily as a manner to detect bugs in the code. The bugs are detected when the code does not act as a consistent solution of the governing equations in the manner desired. This comes when the exact solution to those governing equations does not match the order of accuracy designed for the method. This places code verification as part of software development and quality. This is definitely an important topic, but far from a captivating one. At the same time code verification is distanced from math, physics and aapplication space engineering. Thus, code verification does not feel like science.

This is the disconnect. To be focused upon in proposals and work code verification needs to be part of a scientific activity. It simply is not one right now. Of all the parts of V&V, it is the most distant from what the researcher cares about. More importantly, this is completely and utterly unnecessary. Code verification can be a much more holistic and integrated part of the scientific investigation. It can span all the way from software correctness to physics and application science. If the work involves development of better solution methodology, it can be the engine of measurement. Without measurement “better” cannot be determined and is left to bullshit and bluster.

“Change almost never fails because it’s too early. It almost always fails because it’s too late.”

― Seth Godin

What to do about it?

The way forward is to expand code verification to include activities that are more consequential. To constructively discuss the problem, the first thing to recognize that V&V is the scientific method for computational science. It is essential to have correct code. The software correctness and quality aspects of code verification remain important. If one is doing science with simulation, the errors made in simulation are more important. Code verification needs to contribute to error analysis and minimization. Another key part of simulation are choices about the methods used. Code verification can be harnessed to serve better methods. The key in this discussion is that the additional tasks are not discussed in what code verification is. This is an outright oversight.

Appreciate when things go awry. It makes for a better story to share later.

― Simon Sinek

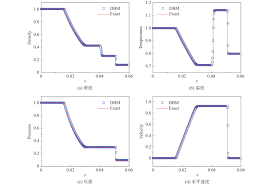

Let’s discuss each of these elements in turn. First we should get to some technical details of code verification practice. The fundamental tool in code verification is using exact solutions to determine the rate of convergence of a method in a code. The objective is to show the code implementation produces the theoretical order of accuracy. This is usually accomplished by computing errors on different meshes.

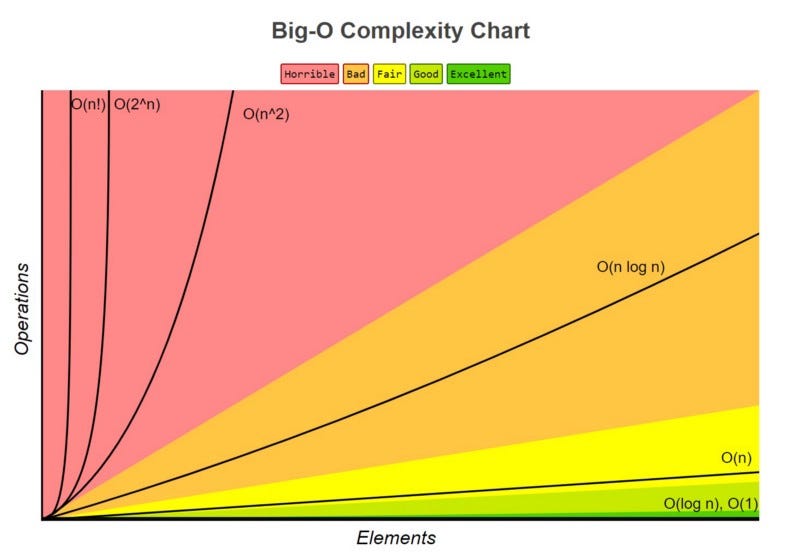

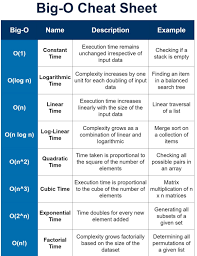

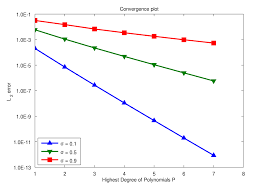

The order of accuracy comes from numerical analysis of the truncation errors of a method. It is usually takes the form of a power of the mesh size. For example a first order method the error is proportional to the mesh size. For a second order method the error depends on the square of the mesh size. This all follows from the analysis and has the error vanishing as the mesh size goes to zero (see Oberkampf and Roy 2010)

The grounding of code verification is found in the work of Peter Lax. He discovered the fundamental theorem of numerical analysis (Lax and Richtmyer 1956). This theorem says that a method is a convergent approximation of the partial differential equation if it is consistent and is stable. Stability comes from getting an answer that does not fall apart into numerical garbage. Practically speaking, stability is assumed when the code produces a credible answer to problems. The trick of consistency is that the method reproduces the differential equation plus an ordered remainder. Now the trick of verification is that you invert this and use a convergent sequences to infer consistency. This is a bit of a leap of faith.

“Look for what you notice but no one else sees.”

― Rick Rubin

The additional elements for verification

The most important aspect to add to code verification is stronger connection to validation. Numerical error is an important element in validation and application results. Currently code verification is divorced from validation. This makes it ignorable in the scientific enterprise. To connect better, the errors in verification work need to be used to understand mesh requirements for solution features. This means that the exact solutions used need to reflect true aspects of the validation problem.

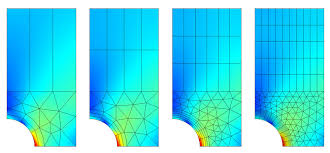

Current verification practice pushes this activity into the background of validation. In doing “bug hunting” code verification, the method of manufactured solutions (MMS) is invaluable. The problem is that MMS solutions usually bear no resemblance to validation problems. For people concerned with real problems MMS problems have no interest, nor guidance for their solutions. Instead verification problems should be chosen that feature phenomena and structures like those validated. Then the error expectations and mesh requirements can be determined. Code verification can then be used as simple pre-simulation work before validation ready calculations are done. Ultimately this will require the development of new verification problems. This is deep physics and mathematical work. Today this sort of work is rarely done.

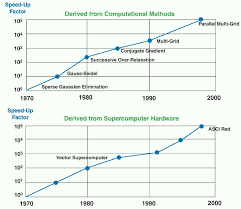

The next big change in code verification is connecting code verification more actively to method-algorithm research. Code verification can be used to measure the error of a method directly. Again this requires a focus on error instead of convergence rate. The convergence rate is still relevant and needs to be verified. At the same time methods with the same convergence rate can have greatly different error magnitudes. For more realistic problems the order of accuracy does not determine the error. It has been shown that low order methods can out perform higher order methods in terms of error (see Greenough and Rider 2005).

“There is no such thing as a perfect method. Methods always can be improved upon.”

– Walter Daiber

In all aspects of developing a method code verification is useful. The base of making sure the implementation is correct remains. The additional aspect that I am suggesting is the ability to assess the method dynamically. This should be done on a wide range of problems biased toward application-validation inspired problems. In terms of making this activity supported by those doing science, the application-validation inspired problems are essential. This is also where code verification fails most miserably. The best example of this failure can be found in shock wave calculations.

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t change it.”

– Peter Drucker

Let’s take a brief digression to how verification currently is practiced in shock wave methods. Invariably the only time you see detailed quantitative error analysis is on a smooth differentable prroblem. This problem has no shocks and can be used to show a method has the “right” order of accuracy. This is expected and common. The only value is the demonstration that a nth order method is indeed nth order. It has no practical value for the use of the codes.

“Measure what is measurable, and make measurable what is not so.”

– Galileo Galilei

Once a problem has a shock in it, the error analysis and convergence rates disappear from the work. Problems are only compared in the “eyeball norm” to an analytic or high resolution solution. The reason for this is that the convergence rate with a discontinuity is one or less. The reality being ignored is that error can be very different (see the paper by Greenough and Rider 2005). When I tried to publish a paper that used errors and convergence rates to assess the method with shock, the material needed to be deleted. As the associate editor told me bluntly, “if you want to publish this paper get that shit out of the paper!” (see Rider, Greenough and Kamm 2007)

Experts are the ones who think they know everything. Geniuses are the ones who know they don’t

― Simon Sinek

Why is this true? Part of the reason is the belief that the accuracy does not matter any longer. The failure is to recognize how different the errors can be. This has become accepted practice. Gary Sod introduced the canonical shock tube problem that bears his name. Sod’s shock tube has been called the “Hello World” problem for shock waves. In Sod’s 1978 paper the run time of different methods was given, but errors were never shown. The comparison with analytical solution to the problem was qualitative, the eyeball norm. Subsequently, this became the accepted practice. Almost no one ever computes the error or convergence rate for Sod’s problem or any other shocked problem.

“One accurate measurement is worth a thousand expert opinions.”

– Grace Hopper

As I have written and shown recently this is a rather profound oversight. The importance of the error level for a given method is actually far greater if the convergence rate is low. The lower the convergence rate, the more important the error is. Thus we are not displaying the errors created by methods in the conditions where it matters the most. This is a huge flaw in the accepted practice and a massive gap in the practice of code verification. It is something that needs to change.

“The Cul-de-Sac ( French for “dead end” ) … is a situation where you work and work and work and nothing much changes”

― Seth Godin

My own practical experience speaks volumes about the need for this. Virtually every practical application problem I have solved or been associated with converges at low order (first order or less). The accuracy of the methods under these circumstances mean the most to the practical use of simulation. Because of how we currently practice code verification applied work is not impacted. There is a tremendous opportunity to improve calculations using code verification. As I noted a couple of blog posts ago, the lower the convergence rate, the more important the error is (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2024/08/14/algorithms-are-the-best-way-to-improve-computing-power/). A low error method can end up being orders of magnitude more efficient. This can only be achieved if the way code verification is done and its scope increase. This will also draw it together with the full set of application and validation work.

More related content (https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2017/12/01/is-the-code-part-of-the-model/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2017/10/27/verification-and-numerical-analysis-are-inseparable/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2015/01/29/verification-youre-doing-it-wrong/, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2014/05/14/important-details-about-verification-that-most-people-miss/,

“If it scares you, it might be a good thing to try.”

– Seth Godin

Roache, Patrick J. Verification and validation in computational science and engineering. Vol. 895. Albuquerque, NM: Hermosa, 1998.

Oberkampf, William L., and Christopher J. Roy. Verification and validation in scientific computing. Cambridge university press, 2010.

Lax, Peter D., and Robert D. Richtmyer. “Survey of the stability of linear finite difference equations.” In Selected Papers Volume I, pp. 125-151. Springer, New York, NY, 2005.

Roache, Patrick J. “Code verification by the method of manufactured solutions.” J. Fluids Eng. 124, no. 1 (2002): 4-10.

Greenough, J. A., and W. J. Rider. “A quantitative comparison of numerical methods for the compressible Euler equations: fifth-order WENO and piecewise-linear Godunov.” Journal of Computational Physics 196, no. 1 (2004): 259-281.

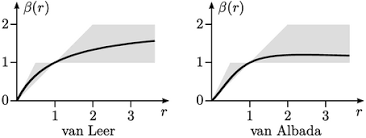

Rider, William J., Jeffrey A. Greenough, and James R. Kamm. “Accurate monotonicity-and extrema-preserving methods through adaptive nonlinear hybridizations.” Journal of Computational Physics 225, no. 2 (2007): 1827-1848.

Sod, Gary A. “A survey of several finite difference methods for systems of nonlinear hyperbolic conservation laws.” Journal of computational physics 27, no. 1 (1978): 1-31.