Tags

tl;dr

I’m getting close to the decision to retire. I’m looking back at my career, trying to put things in perspective. By most accounts, it has been a great career, but it is also short of what it could have been. I’m going to express some genuine disappointment. I’ve seen a lot and accomplished some great things. I’ve talked about my young life, and now I get to my professional career. My years in Los Alamos were the apex of my career. Those years made me who I am as a scientist. I could have done so much more, too, but bad decisions and bad people cost me a lot.

“Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.” ― Seneca

My Early Years at Los Alamos

I arrived in Los Alamos on June 19, 1989, to start work. I got a job in a group that did nuclear reactor safety analysis. They had lots of new money to support the “new production reactor” replacing old Cold War infrastructure. I was beside myself with joy in getting such a great job. I did not realize how fortunate I was. I put in my paperwork for a clearance and started to set up a fully adult life. We rented a place on North Mesa in Los Alamos and my wife started taking classes at the local university extension. For my own part, I took exactly one semester away from school. In the Spring semester, I would return to my pursuit of a PhD. This got to the nature of Los Alamos at that time. The Lab was expansively generous with knowledge and the pursuit of education. My classes were covered by work, and my coworkers were open and generous with their knowledge. I also made a bunch of friends in those years that I keep today.

Little did I know that the world would change dramatically before the end of the year. In November 1989, I walked in from a day at work to something that hit me like a freight train. I walked into the house with my cool Los Alamos work briefcase full of papers to read at night. What I saw caused me to promptly drop it at my feet. I stared at the TV, mouth agape, at people dancing on top of the Berlin Wall. I knew at that moment that everything was going to change, the Cold War was over.

Everything changed over the next few years with how the Lab worked. Change was already taking place with the elements of decline in place since Reagan was elected in 1980. The end of the Cold War just accelerated the process tremendously. Meanwhile, I was focused on finishing my PhD work. I got through with classes and focused on my thesis. As part of this, I wrote a series of papers. The focus was my choice. I had fallen in love with hyperbolic conservation laws and their numerical solution. At Los Alamos, I could dig in and devour the literature. At first, I focused on flux-corrected transport (FCT). Over time, these methods lost appeal because of their lack of mathematical rigor. I was drawn to total variation diminishing (TVD) methods. These methods had a strong mathematical foundation and were a springboard to rigor.

One of my papers tried to draw the linkages between these two families of methods. It was the first paper I wrote in this area. This paper got lost in the review. I had unwittingly stepped in the middle of a little holy war between these camps. At first, I got a review from Ami Harten who said “This is great, publish immediately.” I was over the moon. My second review was from Steve Zalesak who savaged the paper. It was as deflating as Harten’s review was a boost. The paper then slipped into limbo, and five years later I allowed it to be buried. I had moved on. It was a deeply painful lesson about the personal politics of research. It was good work and the analysis was solid. The problem is that it identified the mathematical weaknesses of FCT. This didn’t mean FCT was a bad method, but it did say it had some weaknesses. TVD has other weaknesses like it is too dissipative. The camps were unable to navigate the space between themselves rationally and I was a casualty.

Another highlight of working at Los Alamos is meeting my heroes. While I was at the University of New Mexico, I started to read the works of Frank Harlow. It was the start of my love of numerical methods. At Los Alamos, I met Frank and eventually came to count him as a treasured colleague and friend. I also met a couple of Nobel Prize winners (Bethe and Gell-Mann), and other heroes. The most notable of these heroes is Peter Lax. As I got into modern numerical methods, Peter’s work loomed ever greater. Eventually, Peter visited Los Alamos to help celebrate Burt Wendroff’s 70th birthday. I was able to give a talk to an audience of greats including Peter. This was a real career highlight.

(https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2015/06/25/peter-laxs-philosophy-about-mathematics/)

Finally, in early 1992, I finished my PhD. The godfather of the Los Alamos reactor safety code, Dennis Liles, was my advisor. I had been working on nuclear reactor safety, including developing advanced numerical methods for tracking materials. There, I was able to hone my craft, but it was also severely limited. I needed to move to the core of the Lab from the periphery. The core of Los Alamos is nuclear weapons work, which is done with supercomputers. A job ad in the Lab Newspaper featured my opportunity. My boss knew I needed a new start, and showed me the ad. I made the move. I was ready for new challenges, and they were coming.

Opportunity Knocks

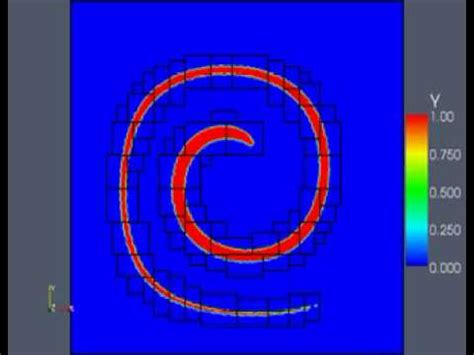

I didn’t make this change without some groundwork. As part of a hair-brained scheme for transforming nuclear waste, I started to study the tracking of interfaces. When solving such problems at Los Alamos, Frank Harlow’s group T-3 is the place to do it. A young staff member, Doug Kothe, was leading the way in this topic. I met Doug to talk about it. As was the nature at Los Alamos in those days, Doug was generous with his time and expertise. This generosity was everywhere in Los Alamos and I could pick the brain of experts all over. The meeting with Doug was the beginning of an incredible collaboration. He and I did some seminal work on volume-tracking methods. It is notable that volume tracking is an essential algorithm in many Los Alamos codes. The paper Doug and I wrote is still my most highly cited work. Moreover, the work we did is still used by the top computer code in Los Alamos to do essential work on our nuclear stockpile.

I also got a huge break in my new group, C-3. I could foster my collaboration with Doug and start working with some other big names on a national project. I started to work on a project for numerical combustion modeling with John Bell (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories, LLNL, those days) and Phil Colella (UC Berkeley). This would be a crash course in all sorts of numerical methods. I would learn compressible flow ala Colella, and incompressible flow ala Bell. I would also learn numerical linear algebra and high-performance computing. The things I learned on this project would change the direction of my career. I did a study of the broad class of incompressible flow solvers that would have likely been capable of being a second PhD thesis. It was an incredible opportunity.

Of course, all of this happened while the Cold War ended and the world changed. But I was sheltered from the fallout. The changes elsewhere in Los Alamos were massive. Nuclear weapons testing had ended, and the Lab’s budget was in freefall. Something new was brewing, the Stockpile Stewardship program, and the idea of simulating weapons on supercomputers was the alternative. I was involved with planning and scoping this program at the outset. Little did I know that this program would fund me for the rest of my career. I also made a move to a new group in the famous (or infamous) X-Division, the Applied Theoretical Physics Division, the belly of the beast. I was going to work in the heart of the nuclear weapons program in the hydrodynamics group. In the meantime, I had bought a house in White Rock (Los Alamos “suburb”), and my first son Kenneth had been born. My wife had finished her bachelor’s degree in business at UNM, too. Los Alamos by in large is a great place to raise kids and a blast from the past in terms of lifestyle.

How did I end up in X-Division?

In the basement in the computing division was Bo’s gym. I would go there during the workday and work out. I would spend a long time on a Stairmaster machine and read technical papers constantly. They would be covered in sweat, and I would pitch them off the machine. This guy would come over and see what I was reading. He took an interest, and it seemed we were interested in the same things. His name was Len Margolin, and he was the group leader for the Hydrodynamics group. Len and I would also form a collaboration that lasted for more than a decade and has echoes today. He was a great boss and is a good friend.

“No matter how bad things are, you can always make things worse.” ― Randy Pausch

The Belly of the Beast

In 1996 I made the move to Len’s group. There was a new program called the Advanced Scientific Computing Initiative (ASCI) that revitalized work in Los Alamos (LLNL and Sandia too). Vistas were opening and work was exciting. The power of possibility was in the air. I got an office in Los Alamos’ old administration building, a bit of a cinderblock shithole that I still have vivid dreams about. I was in Room 247B and next door in 247C was Wen Ho Lee (more on him later). I went about learning as much as I could about how X-Division did its work and how I could contribute. Len gave me a broad aegis to study numerical methods. I did lots of really great things like writing my own Von Neumann-Richtmyer Lagrangian code. I have little interest in such methods, but I found this exercise to be extremely useful. It was part of a heady time of possibility where the future seemed to be created in plain sight.

As part of the growth in ASCI Len hired some heavy hitters from other Labs. One was my old friend from graduate school, Dana Knoll, and his colleague, Vince Mousseau. We began a collaboration on using the multigrid knowledge I had now with Newton-Krylov methods. We were applying it to radiation transport, which is a major focus of X-Division. We did some really great research and wrote lots of highly cited papers.

During this period of time, I had a particular personal moment that stuck out. In all honesty, my early time at Los Alamos was rife with imposter syndrome. Given my history and the talent I was working with, I felt like I was over my head. This was especially true after receiving my PhD, and I started working more closely with the elite. They were accomplished and brilliant. I also had this strong personal sense of responsibility as a breadwinner for my family. Having a second child, Jackson, only compounded this feeling. So I was working very hard and putting in lots of hours.

The issue was that my wife needed more from me in terms of domestic support. This sense of duty was a consequence of the values and priorities of a man as I was raised. These were also horribly antiquated views. Finally, this all came to a head. I had to choose, and the result was a terrifying series of panic attacks, the resolution of which left me with the need to rebalance my life. I needed to be more of a parent and less of an over-achiever.

I also started to work with Jim Kamm at that time. Jim and I worked incredibly well together with our strengths complimenting each other phenomenally. I would work with Jim continuously for nearly 20 years until he disappeared in 2017. Jim also marked my entry into the verification and validation (V&V) program, which has been a focus since 1998. A big part of that program is Tim Trucano, who might rightly be called the father of it. He and I met in Washington, DC in January 1999 at a Blue Ribbon Panel review of ASCI. I gave the briefing on Hydrodynamics, and Tim on V&V. It was a huge shift in the ASCI program, and I was part of it. Tim is now a dear friend.

The “Troubles”

As things moved forward, the year 1999 marked a major change in the Lab’s fortunes. It was the beginning of a series of scandals that destroyed the Lab’s reputation. In late November, my wife and I were going to a dinner party, and on the way, we listened to the news that talked about potential spying at Los Alamos. It mentioned the suspect was a Chinese-American scientist. I quipped to her that there was a guy at work who seemed suspicious if I had to guess. I was thinking of Wen Ho Lee. Two weeks later, he was arrested. It was announced by Peter Jennings on the Nightly National News. It felt like a gunshot. I was stunned. The lead story in the country was all about someone I knew well and worked with. Nothing would ever be the same again at Los Alamos. The havoc this wrought was pure destruction.

My own connection to these events is oddly coincidental. The father of my best friend from high school presided over Wen Ho’s first bail hearing. He was denied bail there, a decision that was repeated during time before his trial. He was held in bad conditions as well. Surely a small, slight Chinese man charged with treason would have been killed in short order in the general prison population. There are lots of criminals who consider themselves patriots. Back at work, things just spiraled into the bizarre as my highly classified workplace came under endless scrutiny and attention. Some of that attention would be public through coverage by the media, and other attention through legal proceedings.

The case against Lee was shaped by politics rather than common sense. The case was also driven by the same toxic politics that have exploded over the past 20 years. In the world of stockpile stewardship, the computer codes he downloaded were the focus of the investigation. This focus was driven by the computer code focus of stockpile stewardship and the ASC program. It is arguable—and I think correctly so—that this was the weakest case against him. Events would seem to have validated my view. Along the way, I was amongst the people interviewed by the FBI about the case. My work and Wen Ho’s were close enough that entanglements were certain. People I knew would be talked about in court and testify as well. The overall feeling was surreal.

As time went by, the trial was looming in the future. Events would intercede to take things to another level. In May 2000, the forest service started a controlled burn in Bandelier National Monument. It quickly turned into an uncontrolled massive forest fire. The fire streamed North fueled by a drought-ravaged forest and springtime winds. Eventually, it threatened the city of Los Alamos and the Lab. We were all evacuated from town and the fire became an inferno. Again, Los Alamos was atop the national news. Meanwhile, something else was brewing at the Lab, triggered by the fire. Some highly classified hard discs had gone missing. Someone went to secure them from the potential fire, and they were gone. Again, this event happened in a place I knew and had been in. People I knew well were at the core of it.

The Lab looked in vain for the hard discs for a month. Right before the time expired, we had a meeting of X-Division. We were implored to tell them if we knew about this thing they were missing. They couldn’t tell us what it was that was missing due to security rules. It was more surreal. The capper to the meeting was its closing. Our Associate Director, Stephen Younger, closed it by threatening everyone. He said, “If you know something speak up, remember what happened to the Rosenburgs.” No one did. This time the FBI came in force. Agents were everywhere.

The hard discs would be found eventually a few doors down from where they were lost, behind a photocopier by a weapons’ designer. Before that, something even bigger happened. The FBI mistreated one of the people responsible for the hard discs (although unlikely to be responsible for them being missing). This enraged the Los Alamos coworkers. It ended up with a cooling-off period after one of the weapons designers gave the FBI agents a Nazi salute. The saluted agent happened to be Jewish. So the shit hit the fan. The abused staff member was also friends with the star witness in the Wen Ho Lee case. So he ended up not favorably disposed toward the government and its case. He testified in the case, and it did not go well for the prosecution. Soon, the case against Wen Ho was dropped. Nonetheless, the damage was done. Worse yet, more damage was coming.

The awful events were not over yet by a long shot. It was late 2003. I personally was doing some soul- and job-searching. I had a couple of things I was trying. I had applied for and interviewed for a job at Lawrence Livermore, and they offered me the job, but the pay offer was crappy. My wife didn’t have a job out there, either. Real estate in the East Bay was insanely high (and still is). I also applied for a management job at Los Alamos. I remember not getting the management job, and in the meeting telling me this, being told “You are too decisive,” whatever that means. When the meeting ended, my Division Leader was called away by something happening that was both troubling and familiar. More classified hard discs were missing. Los Alamos also had a new lab director, Pete Nanos, a former vice admiral in the navy. More importantly, Pete was a fucking asshole.

The missing hard discs were bad enough, but then another thing went wrong. In a lab, a young student intern was hurt. She was observing the alignment of a laser, and it shined directly into her eye. Nanos lost his shit and shut the lab down. There was to be no work, and we all needed to be punished. He also insulted the staff calling them “Cowboys and Buttheads.” He dressed down people in public. All of this is a failure to do anything to help matters. (As I look back, the style was reminiscent of our current President-elect.) Nanos was a master of demotivation. He was easily the worst Director Los Alamos ever had. He left nothing but destruction in his wake.

Personally, I was in a weird place. I had spent the previous week at a conference in Toronto. I had decided that I could not take the Livermore job. It was too risky, and we would have to sacrifice too much. We would have also gotten stuck in financial and real estate collapse (although I still did, just not catastrophically). I would stick with the job at Los Alamos, even with the Lab shutdown. I was headed to Cambridge for another conference the next week. On my way home to do laundry and pack for the trip, I received three calls from management telling me I could not go. I spent the weekend getting permission to e-mail my talk to a Livermore colleague to present the talk for me. This was how ridiculous the whole situation was.

I went to work Monday and accepted a position as a temporary deputy group leader. My friend, John, the group leader, was in Scotland, out of contact on vacation (he got that job over me). The week spiraled out of control. Our permanent deputy group leader retired on the spot midweek as the environment of fear was overwhelming. So, by the end of the week, I was the group leader, albeit for a short time. This period produced resistance at the Lab amongst the staff as Nanos burned all the bridges. He was despised by all. He offered no respect and received none in return. For example, he committed a security violation by speaking openly about an active investigation. The authorities let him off the hook by declassifying it. Nanos deserved no respect (feels similar to someone else, doesn’t it?).

Eventually, Nanos departed as an utter failure. He was replaced, but the damage was almost immeasurable to the Lab. During this time, the University of California was replaced as management. Too much damage had been done to the Lab’s reputation. Gone was the generous culture I prized and gone was the public trust. Management was replaced by a multi-headed hydra of corporate overseers. Amongst them is the endlessly awful, incompetent, and corrupt Bechtel who used Los Alamos to dump its corporate toxic waste. UC still had a role and Livermore managers came in as directors. They were very good and ultimately fought endlessly with the idiots from Bechtel.

I’ll relay one more story of scandal to close out the lunacy of the time. One of the small problems involved a menial worker who was scanning old documents into an electronic form. The work was classified, and she fell behind, so she took it home. She was kind-hearted and let a meth-head sleep on her couch. He boosted the USB drive and sold it. In the final analysis, I knew the meth head. He was the brother of my son’s teammate on the local soccer team. Small towns make for weird connections!

The thing that stands out about all this was how close all these troubles were to my life. I always knew someone at the center of them. It was part of being in a small town and being close to the center of the Lab’s core mission.

“You gain strength, courage and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face. You are able to say to yourself, ‘I have lived through this horror. I can take the next thing that comes along.’ You must do the thing you think you cannot do.” ― Eleanor Roosevelt

I would be remiss in not talking about my technical work at this time. One of the best and most successful projects I’ve ever worked on happened amid all this chaos. Together with Len Margolin, we studied at topic known as “implicit subgrid modeling” under the auspices of laboratory-directed research and development (LDRD). The output from this project was incredible, including a book and a bevy of highly cited papers. It is a continuing source of great pride for me. It serves as a sterling example of what is possible with the right environment and a generous culture.

It also is a project that highlights what is (or was) great about Los Alamos. This modeling applies to turbulence, and turbulence was a topic that used to scare the shit out of me. The combination of intellectual generosity and mission-focused motivation. Back in late 1997 during the holiday break, I decided that I needed to learn about turbulence. I started off by reading a whole slew of books and papers. The key was that I also could tap the experience and knowledge of experts at the Lab. I could be exposed to the brilliance of some of the greatest minds on the subject. I could grow into the topic and gain the confidence needed to contribute to progress. It is this spirit that the “troubles” destroyed. The damage was to the Lab, the nation and the world, and to scientific progress.

In this same time period I also had the opportunity to write my first book. I was approached by an acquaintance, Dimitris Drikakis from the UK. He was part of a contract with Springer-Verlag for a book. It was a follow-on to an immensely successful book by Toro. It turned out that Toro had run into some significant personal problems, and had to drop out. Dimitris approached me and I accepted. I had a large body of work in the focal area for the book, low-speed and incompressible flows. He and I worked on the book including a week where I hosted Dimitris. I had the lab’s support and resources. I will say that the support from Springer-Verlag left much to be desired. This later came into real contrast with the incredibly good experience with Cambridge University Press. Still I had written and published my first book.

I took a management job for a year there working for Paul Hommert. Paul was a great manager (although at Sandia, I would learn all about his shortcomings). It was a great experience, but largely told me that managing was not how I wanted to spend my life. There was a moment I’ll always remember. One of my peers, Bob Little told me about handing Wen Ho Lee his at risk for RIF notice. He wondered what that would mean for how this played out. We would not name people at risk for RIF. I would still tell my staff member of his danger so he could get his work and personal life together in time to matter.

It was at this time that I explored working at Sandia. I met with Tim Trucano and Randy Summers at a classified conference in 2006. They wanted to offer me a job and I wanted out of the nuthouse.

Next, I will discuss my move to Sandia National Labs in February 2007.

“Be yourself; everyone else is already taken.” ― Oscar Wilde

References

Rider, William J., and Douglas B. Kothe. “Reconstructing volume tracking.” Journal of computational physics 141, no. 2 (1998): 112-152.

Rider, William, and Douglas Kothe. “Stretching and tearing interface tracking methods.” In 12th computational fluid dynamics conference, p. 1717. 1995.

Grinstein, Fernando F., Len G. Margolin, and William J. Rider, eds. Implicit large eddy simulation. Vol. 10. Cambridge: Cambridge university press, 2007.

Drikakis, Dimitris, and William Rider. High-resolution methods for incompressible and low-speed flows. Springer Science & Business Media, 2005.

Puckett, Elbridge Gerry, Ann S. Almgren, John B. Bell, Daniel L. Marcus, and William J. Rider. “A high-order projection method for tracking fluid interfaces in variable density incompressible flows.” Journal of computational physics 130, no. 2 (1997): 269-282.

Margolin, Len G., and William J. Rider. “A rationale for implicit turbulence modelling.” International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 39, no. 9 (2002): 821-841.

Margolin, Len G., William J. Rider, and Fernando F. Grinstein. “Modeling turbulent flow with implicit LES.” Journal of Turbulence 7 (2006): N15.

Rider, William J. “Revisiting wall heating.” Journal of Computational Physics 162, no. 2 (2000): 395-410.

Rider, William J., Jeffrey A. Greenough, and James R. Kamm. “Accurate monotonicity-and extrema-preserving methods through adaptive nonlinear hybridizations.” Journal of Computational Physics 225, no. 2 (2007): 1827-1848.

Greenough, J. A., and W. J. Rider. “A quantitative comparison of numerical methods for the compressible Euler equations: fifth-order WENO and piecewise-linear Godunov.” Journal of Computational Physics 196, no. 1 (2004): 259-281.

Kamm, James R., Jerry S. Brock, Scott T. Brandon, David L. Cotrell, Bryan Johnson, Patrick Knupp, William J. Rider, Timothy G. Trucano, and V. Gregory Weirs. Enhanced verification test suite for physics simulation codes. No. LA-14379. Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), Los Alamos, NM (United States), 2008.

Rider, William J., and Len G. Margolin. “Simple modifications of monotonicity-preserving limiter.” Journal of Computational Physics 174, no. 1 (2001): 473-488.

Mousseau, V. A., D. A. Knoll, and W. J. Rider. “Physics-based preconditioning and the Newton–Krylov method for non-equilibrium radiation diffusion.” Journal of computational physics 160, no. 2 (2000): 743-765.

Knoll, Dana A., and William J. Rider. “A Multigrid Preconditioned Newton–Krylov Method.” SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 21, no. 2 (1999): 691-710.

Knoll, D. A., W. J. Rider, and G. L. Olson. “Nonlinear convergence, accuracy, and time step control in nonequilibrium radiation diffusion.” Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 70, no. 1 (2001): 25-36.

Bill,

I just happened on this from your Facebook post. I followed the link to Part 1 and read it as well. Thank you for memorializing not only your personal odyssey, but the evolution of the National Labs and typified by LANL.

The LANL management and the FBI really messed up the investigation and public relations about Wen Ho Lee. The guy committed one security breach after another, but the FBI insisted on pursuing the espionage angle at the expense of charging the provable, serious, criminal, and intentional violations or security.

Anyway, good articles.

Stay in touch.

Dan