Tags

tl;dr

Nobody enjoys failure. It is generally not celebrated. In fact, it is generally feared and reviled. It is rarely seen as the origin of true success, but that is what it is. Innovation and creation often come from failure. Yet, we see a lack of encouragement to allow failure. Instead, it is feared by most. Instead of harnessing failure, we tend to hide it. In doing so we miss the opportunities for amazing progress. If used properly, failure is the path to learning and growth. In it, we can find rebirth and redemption. Without it, we sink into stagnation and mediocrity.

Like many posts of the past, I am returning to writing about a talk that I am to be giving. The issue is that it is a five-minute talk. What I have here is not five minutes of content. So, I need to boil it down to the essence that’ll be work for later. For now, enjoy the full treatment this topic deserves. At the end of the new material is a reprint of a blog post written for Sandia Labs internally.

Fear of Failure

“Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.” ― T.S. Eliot

Failure is bad.

Failure is embarrassing.

Failure should be avoided.

Failure is to be feared.

If we listen to our leaders at work and in politics we hear celebrations of success. Our meetings are full of stories of accomplishments and victory. When someone does something well it is promoted as the thing for others to follow. If you want to be that person you should do everything possible to succeed. Our leaders are selling us a lie, and to succeed you should first fail instead. Successes like we hear about are usually half the story or less. Our leaders are telling us half-truths that make success seem like a simple story. It is not. More often than not, success, true success is built upon failure.

If the story of success does not include failure as an integral part of it, that success is likely hollow. If there is not an element of failure, the success is likely the product of low expectations. Rather than aim high and try to succeed greatly, we choose easy expectations. Very rarely does great success come without difficulty. Those difficulties are numerous failures. Yet when we listen to what our managers say and do, failure is to be avoided. Failure is a source of shame. Failure is to be feared. This is management malpractice. We are missing any opportunity for greatness in the process.

“life is truly known only to those who suffer, lose, endure adversity, & stumble from defeat to defeat.” ― Anaïs Nin

I wrote a blog post for Sandia recently on the subject (the November ND Post). It was a nice piece although the ground rules for writing at Sandia are different than here. It was far more vanilla and bland than what I’d normally write (because Sandia requires dull flavorless prose). Of course, this is actually part of the problem with the institution. Part of failure is taking risks, and in writing maybe offending someone is a risk. Fuck people like that! I’m going to be a lot spicer here. I will also include the actual post at the end of this one along with links to earlier takes on this important, timely, and timeless topic.

Failure is the Route to Success

“Victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan.” ― John F. Kennedy

If we could get our managers to talk about failure, it would be a breakthrough. I’ll not hold my breath on this happening. Managers are much better at pretending everything is great. They like to believe that success can happen without difficulty. Yet difficulties and failures are usually essential to any story of success. These failures are actually the interesting part of the story too. The result is a far more boring version of what we do.

Failure is essential to learning. Research is learning. So the obvious conclusion is that if we want to have research success and learn more, we need to fail. Part of embracing failure is pushing the boundaries of what you know, or what you can do. The key is to learn from those failures. The key is to use failure to build yourself. I can provide a few lessons from my own life as object lessons in failure.

“In any case you mustn’t confuse a single failure with a final defeat.” ― F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tender Is the Night

I’ve written several times about the failure at the heart of one of my greater achievements professionally. My most cited paper is on a numerical method called volume tracking. At the weapons labs, this is a very important method. In the 1980’s David Youngs from AWE introduced a new way to do this that was quickly adopted in the USA too. In the early 1990’s I became interested in this method at Los Alamos. It was essential to how our weapon’s codes simulated multiple material hydrodynamics. This was the thing I wanted to do and become an expert at. I’d already contacted Doug Kothe in the Theoretical Division and started building a collaboration. The way I approached learning about it was the tried and true method of first reproducing the state of the art. Once you can reproduce the state of the art, you then try to advance it. This is the way expertise is gained. You are not an expert by knowing the state of the art; you are an expert when you can advance it.

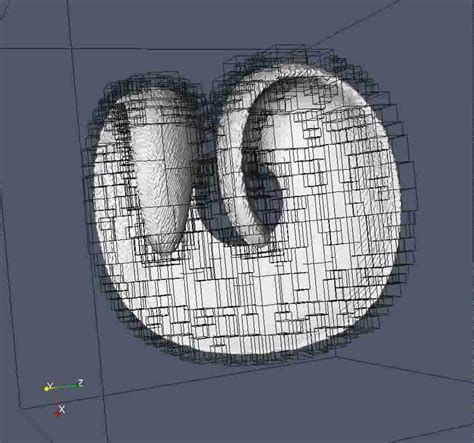

I had seen how Youngs’ method was coded up at Los Alamos, and I worked to independently implement it myself. I did this successfully and set about testing the method using verification problems. These included some new problems I had adapted to testing volume tracking more strenuously (my first advance of the state of the art). Everything was working as desired. Then I tried to improve the method and everything went awry. Suddenly my attempt was a failure! I could never debug it properly. The way the method was written at Los Alamos had too much cyclomatic complexity (which is logical intensity). I needed to go back to the drawing board. I went back to the origins of the method and decided to try something new. I would compose the method through computational geometry operations. Suddenly the implementation was tractable and successfully debugged. We published the method along with our new tests. This paper now has more than 2000 citations. Even better the actual code I wrote is still being used by Los Alamos in one of its mainstream codes.

All of this success is founded on a failure. Without the failure, the success would have been less.

“Better a cruel truth than a comfortable delusion.” ― Edward Abbey

In a greater sense, the greatest successes of my life are all founded on huge failures. Each of these failures was heavy and inescapable. Each pushed me back to the drawing board to reimplement part of my life. Each time I needed to rethink something essential to how I lived. My life today is almost entirely shaped by these three episodes. Without the failures, I would be someone different, far less successful, or happy.

I’ve talked about the end of my first year of grad school. I dropped a class and did poorly in another during the Spring Semester. Each class was essential to how I wanted my future to play out. Together these failures showed me that my dreams were dying. If I didn’t change I wouldn’t accomplish my goals. I had to completely rethink my approach to school. The way I had succeeded as an undergrad or high school student did not work. I needed to be mre serious and put much more effort into my studies. I made a huge investment in time and effort to become a different student. I changed how I approached learning and acting in a school setting. I became completely different in academics. This change laid the groundwork for success at Los Alamos too.

“Everything tells me that I am about to make a wrong decision, but making mistakes is just part of life. What does the world want of me? Does it want me to take no risks, to go back to where I came from because I didn’t have the courage to say “yes” to life?” ― Paulo Coelho

Later on in my time at Los Alamos, I had a string of panic attacks. My work-life balance was completely out of whack. I was working way too hard and sacrificing too much as a husband and parent. I needed to rebalance my life. The way I approached my early career was no longer working for the full breadth of my life. In that decision, I gave up on my imposter syndrome and accepted my success. I walked away as a better husband, better father, and a confident (perhaps even imposing) scientist. I changed myself from the man who had nearly fallen apart. A truism learned through the pain of this failure is that it is the source of wisdom.

Later on, as I approached midlife, I found that I was not happy hiding myself at work. The result was tattoos and a more open self away from work. I also found that my marriage was not monogamous. In the wake of that I discovered my natural tendency toward open love and non-monogamy. In the failure of my traditional monogamous marriage, a new relationship was born. I became a new version of myself with a new marriage. I’ve often said that I have had three different marriages to the same woman. Each rebirth had us growing together instead of apart. Every time I failed, I stepped up to rebuild my life from the ground up. I needed to change and all my success is found by learning from those failures. Everything I value today comes from the fountain of growth that are failures.

“Confusing monogamy with morality has done more to destroy the conscience of the human race than any other error.” ― George Bernard Shaw

Barriers to Progress

The verification and validation (V&V) program offers a unique window into attitudes toward failure. If functioning properly V&V would find failures all the time. In fact, it does, but usually, the response is to paper over or cover up the failure. Rarely, if ever, does the failure result in an appropriate action to fix the underlying problem. There seems to be an attitude that everything should be working now. We should just be able to model and simulate everything perfectly. An honest assessment of validation would tell us that our models are deeply imperfect. We resort to calibration of virtually every serious model. Yet we sell it as the epitome of success. Instead, it is a failure we haven’t learned from.

“The only way to find true happiness is to risk being completely cut open.” ― Chuck Palahniuk

With the practice of verification, this tendency is even worse. Part of it is how verification is packaged. Code verification is about finding bugs. A code bug is just wrong and simple to fix. Solution verification is just an exercise in numerical error and after the exascale program that should be a thing of the past too. Both of these viewpoints are utterly wrong-headed. Verification can find fundamental issues with a code. These are places where the code simply does not work at all. Our shock codes offer a perfect example of this, yet our managers ignore these problems. They make excuses to justify their inattention to serious issues. This is the wrong sort of failure and they desire to not even admit it. Numerical errors still vex our calculations even with our limitless computing power (especially compared to 30 years ago). Instead, we embrace the view of success and push failure away.

Almost nothing we do spells out our unhealthy view of failure like V&V does. It holds a mirror up to our capabilities and often shows our faults. Most of the time is a response that screams “our shit doesn’t stink!” After ignoring the evidence you are not better, and your shit still stinks.

“The purpose of life is to be defeated by greater and greater things.” ― Rainer Maria Rilke

It might be very good to look in the mirror. Are you an “A” student always chasing the top grade in a class? This might describe a lot of you, and it might be the thing holding you back. If you end up afraid to fail, your growth will end. All you’ll be good at is what others created. You will never create anything of your own. Creation is an act of destruction too. You are destroying barriers and creating new paths where none existed before. Sometimes the limits you learned of need to be unlearned. This is the art of failure in the right way. Too many great students cannot throw off the limits of being right and let themselves be wrong. Only through being wrong can a new path be crafted leading to genuine innovation.

Our expectations of ourselves are often our worst enemy. Sometimes we avoid failure because of shame. We see failure reflecting on our qualities. The right way to see failure is feedback. We are being offered a chance to learn about what is needed for success. The variable is the extent of our grasp for success. This is a key point: if you never fail, you aren’t trying. You very clearly are not performing anywhere close to your potential. Lack of failure is actually a red flag. The only way to grow and learn is to fail. Having a distinct fear of failure is a fear of growth and change. Failure is about defining your limits and working past them.

“Life is to be lived, not controlled; and humanity is won by continuing to play in face of certain defeat.” ― Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

A great way of seeing this is through the concept of flow. Flow is where you become fully enveloped in a task with time melting away. One of the most common ways to experience flow is play. If you are playing and fully enjoying yourself with a pure focus, you are in the flow. The key to being in flow is a degree of challenge that requires you to be fully engaged. Challenge means failure is always a possibility. Success is important too. Flow comes from being close to the edge of your competence. Results are a mix of success and failure. You have mostly success keeping you encouraged, but enough failure to grow, learn, and require full attention. A great question is what gets you to flow? Does work ever put you in this state? If not, how can it?

What gets me into a state of flow? At work, I get into the analysis of numerical methods either deriving them or finding their stability or accuracy. My tool of choice is Mathematica. I used to get into flow while running especially in Los Alamos as my mind would wander and free associate. Running is one of the things I really miss about getting older. I also got into flow while refereeing soccer. I had limits to my competence as a ref, and it always pulled me into full attention. Really great sex can produce a flow state too. Part of this admission is the connection of sex to play along with the possibility of failure. A flow state is one of the greatest feelings in life.

What really stands in the way of success. Fear! So many of us are afraid of failing because somehow it will reflect on our worth. There is a sense of shame that powers a lot of this fear. This is hopelessly a misguided principle to adopt. Sacrificing greater success to avoid the fear of failing is worse than cowardice. It is a denial of the potential for growth and the expansion of knowledge. Life is about learning, growing and changing. As always this is a voyage into the unknown, and unknown is where fear lives. Only through the encouragement and trust of our fellow travelers can this voyage be safely taken. Unfortunately in recent times the fear of failure is real. It is real because those in positions of power will attack it as if it was a personal failing. This is simply abuse of power in the worst sense. It is outright incompetence and an invitation to mediocrity. My greatest fear is that we’ve already embraced mediocrity fully and our failure is complete.

“Forget safety. Live where you fear to live. Destroy your reputation. Be notorious.” ― Rumi

Take the Leap

“You cannot swim for new horizons until you have courage to lose sight of the shore.” ― William Faulkner

Honestly when I think of today’s labs, I rarely think of failure. We have a bunch of employees who may have never failed, or at least admitted to it. If they did fail they might try to hide it from view. We need some fucking leadership with balls to break the mold. Let’s talk about how to fuck up well. The way to really kick ass is to fuck up, admit it, learn a thing or two, and try again, try better. Take a chance and risk it all for a bigger reward. What I see instead is extremely competent mediocrity. Taking a risk recognizes the virtuous cycle of failing, with learning and growing from the experience. The need to get out of our collective comfort zones and push the boundaries. We need to trust ourselves and each other and embrace failure.

Failure is good.

Failure is necessary.

Failure should be sought.

Only fear the failure that you don’t learn from.

I’ve been writing about this for years with themes on failure, risk and trust part of this witch’s brew of dysfunction. The problems I discuss here have been on my mind for years.

My post for Sandia National Labs’ ND Blog

Failing as a Path to Success

November 4, 2024 | Published by ndcomms admin

by Bill Rider

“I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. 26 times, I’ve been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.” – Michael Jordan, American businessman and former basketball player. Widely considered one of the best basketball players of all time

If you know anything about basketball, you know that Michael Jordan (MJ) is the Greatest Of All Time (GOAT). Even after the storied careers of LeBron James and Kobe Bryant, MJ still holds that title. His highlight reels are jaw-dropping even now, twenty years after he last played. Jordan knows a thing or two about success and greatness: he won six NBA championships and an Olympic gold medal. And one thing that MJ understands better than anyone is that all success is built on failure. He is the epitome of Nike’s slogan, “Just Do It.”

The foundation of excellence and success is failure

MJ was a master of being in the zone and teams were constantly struggling to pause his pace of play. Maybe you, too, have been doing something and suddenly realized hours have melted away. If so, you’ve experienced something called “being in a state of flow.” I experienced flow when I started writing this first draft: the words just effortlessly appeared on the page. This “flow” concept was discovered by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who found that to achieve this state, one must be challenged by the task. He stated that one should be failing at a task between 20-30 percent of the time. Fail too much, and you’ll be discouraged; fail too infrequently, and you’ll be bored. One needs a delicate balance between those extremes. People who achieve excellence in all forms of endeavor experience flow in the process. The lesson is that failure is necessary to achieve optimal performance.

Failure’s role in success

Speaking of optimal performance, I’m sure we can all be proud of the United States’ moon landing in 1969. But did you know this massive success was built on numerous spectacular failures? Early on, the American rocket program experienced repeated launch pad explosions and other mishaps. During the height of the Cold War, the United States was in a neck-and-neck battle for scientific superiority with the Soviet Union, and they already beat us into space with Sputnik 1 and sending the first human into orbit around the Earth. Yet we persisted. Even with further setbacks, such as the disastrous Apollo 1 fire that tragically killed three astronauts, we persevered and became the first to put man on the moon. This event stands as a pinnacle of American achievement.

Our nuclear weapons program is also filled with stories of failure paving the way to success. In 1944, the Manhattan Project was in the midst of developing the first atomic bomb, and Sandia was just a division of Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). Part of the Manhattan Project involved having two physicists (Hans Bethe and Richard Feynman, both of whom later won Nobel Prizes in Physics in consecutive years in the 1960s) simulate an implosion on a computer using two separate algorithms: one developed by physicist Tony Skryme and the other by another brilliant mind of the 20th century, John von Neumann. Notably, Bethe and Feynman had spectacular failures in their attempts when using Von Neumann’s algorithm. They did have success in the spring of 1944 when using a completely different method developed by Skryme.

However, the algorithm developed by von Neumann was considered more critical to advancing nuclear weapons. So, after WWII, failure did not deter LANL from pursuing improvements to von Neumann’s method. Another enterprising genius, Richard Richtmyer, found a way to make von Neumann’s method work, and this has since become the absolute workhorse of nuclear weapons design. In fact, the failure of the original method and the ability to learn from it paved the way for a technique still in use today. This method has been used to design the entire stockpile, save for those first couple of designs. (See: Morgan, Nathaniel R., and Billy J. Archer. “On the origins of Lagrangian hydrodynamic methods.” Nuclear Technology 207, no. sup1 (2021): S147-S175.)

Failure as a vehicle for greater discovery and success

In the mid 1990s when I was working at LANL, I wrote a paper with colleague Doug Kothe (our current Division 1000 Associate Laboratories Director), and this paper has now been cited over 2,000 times (See: Reconstructing Volume Tracking). The computer code we described is still being used in one of the main stockpile analysis codes at LANL. This is a story of success, but it didn’t start that way; it was failure that laid the foundation.

One of the key methodologies in weapons’ codes at LANL is interface tracking, and a specific method used in many of these codes was developed by British scientist David Youngs, MBE. I knew mastering this code was important to the Lab’s mission, so I set about to implement the code from scratch and then improve it. To my delight, I succeeded and then went about creating necessary improvements. At this point, unfortunately, everything fell apart. My implementation was too complex and ultimately proved impossible to debug.

I went back to the drawing board. First, I needed to learn a totally new field of computational geometry. Next, I devised a way to implement the method that was simple and easy to debug. Now I could improve the method without issues, and all because I had gone through an earlier disaster. Without my failure, the creation of something better would never have happened. Looking at these codes today, one can see they are implemented as I discovered them. I crucially changed a fundamental method and contributed to an important methodology for simulating our stockpile, and all of this success was based on a failure.

Failure as a goal

I leave you with some words of wisdom: embrace your failures. Sandians aren’t going to fill out our annual goals with all the failures we hope to make this year, but maybe we should! Ironically, we might succeed more and more grandly if we failed more and more consistently. This is only true if we fail the right way – if we learn from our failures and use them to fuel something greater. Failure is the lifeblood of all success. We should embrace it.

“I know fear is an obstacle for some people, but it’s an illusion to me. Failure always made me try harder next time.”

Michael Jordan, GOAT