tl;dr

The practice of verification is absolutely essential for modeling and simulation quality. Yet, verification is not a priority; quality is not a priority. It is ignored by scientific research. This is because verification is disconnected from modeling. Also, it is not a part of active research. The true value of verification is far greater than simple code correctness. With verification, you can measure the error in the solution with precision. Given this, the efficiency of simulations can be measured accurately (efficiency equaling effort for given accuracy). Additionally, the resolution required for computing features can be estimated. Both of these additions to verification connect to the broader scientific enterprise of simulation and modeling. This can revitalize verification as a valued scientific activity.

“Never underestimate the big importance of small things” ― Matt Haig

The Value of Verification

“Two wrongs don’t make a right, but they make a good excuse.” ― Thomas Szasz

Conceptually, verification is a simple prospect. It has two parts; is a model correct in code and how correct is it? Verification is structured to answer this question. Part one about model correctness is called code verification. Part two is about accuracy called solution verification. This structure is simple and unfortunately lacks practical priority. This leads to the activity being largely ignored by science and engineering. It shouldn’t be, but it is. I’ve seen the evidence in scientific proposals. V&V is about evidence and paying attention to it. There is a need to change the underlying narrative around verification.

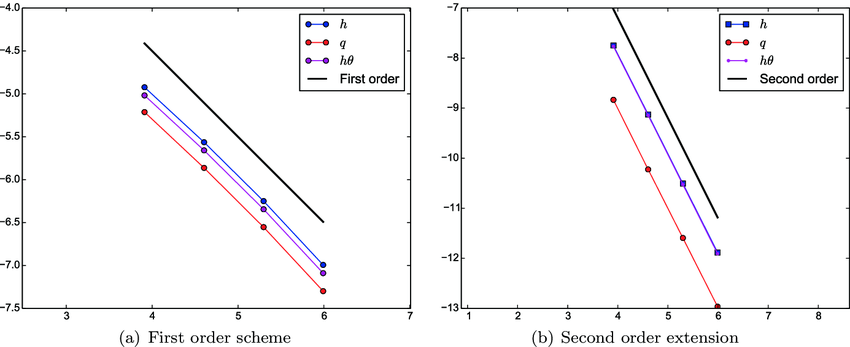

Under the current definition, code verification relies upon determining the order of accuracy for correctness. There is nothing wrong with this. The order of accuracy should match the design of the code (method) for correctness. This is connected to the fundamental premise of advanced computers. More computing leads to better answers, This is the process of convergence where solutions get closer to exact. This produces better accuracy. Today this premise is simply assumed and evidence of it is not sought. Reality is rarely that simple. Solution verification happens when you are modeling and do not have access to an exact solution. It is a process to estimate the numerical error. These two things complement each other.

“The body of science is not, as it is sometimes thought, a huge coherent mass of facts, neatly arranged in sequence, each one attached to the next by a logical string. In truth, whenever we discover a new fact it involves the elimination of old ones. We are always, as it turns out, fundamentally in error.” — Lewis Thomas

In code verification, you can also computer the error precisely. The focus on the order of convergence dims the attention to error. Yet the issue of error in science is primal. Conversely, the focus on errors in solution verification dims the order of convergence there. In doing work with verification both metrics need to be focused upon equally. Ultimately, the order of accuracy and diminishing of error should be emphasized.

As will be discussed later, the order of accuracy influences the efficiency mightily. A broad observation from my practical experience is that the order of accuracy in application modeling is low. It is lower than expected in theory. It is lower than the method designed going into codes. Thus, the order of convergence actually governs the efficiency of numerical modeling. This is combined with the error to determine the efficiency of the simulation.

“The game of science is, in principle, without end. He who decides one day that scientific statements do not call for any further test and that they can be regarded as finally verified, retires from the game.” — Karl Popper

Why Verification is Broken?

Verification is broken because it is disconnected from science. It has been structured to be irrelevant. In reviewing more than 100 proposals in modeling and simulation over a few years this is obvious. Verification as an activity is beneath mentioning. When it is mentioned it is out of duty. It is simply in the proposal call and mentioned because it is expected. There is little or no earnest interest or effort. Thus the view of the broader community is that verification is an empty activity, not worth doing. It is done out of duty, but not out of free will.

I should have seen this coming.

“True ignorance is not the absence of knowledge, but the refusal to acquire it.” — Karl Popper

Back in the mid-oughts (like saying that!) I was trying to advance methods for solving hyperbolic conservation laws. I had some ideas about overcoming the limitations of existing methods. In doing this work it was important to precisely measure the impact of my methods compared with existing methods. Verification is the way to do this. I highlighted this in the paper. The response to the community via the review process was negative,… very negative,… very fucking negative.

In the end, I had to remove the material to get the paper published. I got a blunt message from an associate editor, “if you want the paper published, get that shit out of your paper”. By “shit” they meant the content related to verification. I’ll also say this is someone I know personally, so the familiarity in the conversation is normal. Even worse this comes from someone with a distinguished applied math background with a great record of achievement. You find that most of the community despises verification.

I will note in passing that this person’s work actually does very well in verification. In another paper, I confirmed this. For more practical realistic problems it does far better than a more popular method. It would actually benefit greatly from what I propose below. What had become the publication standard was a purely qualitative measure of accuracy for the calculations that matter. Honestly, this attitude is stupid and shameful. It is also the standard that exists. As I will elaborate shortly, this is a massive missed opportunity. It is counter-productive to progress and adoption of better methods.

I found this situation to be utterly infuriating. It was deeply troubling to me too. When I stepped back to look at my own career path I realized the nexus of the problem. Back in the 1990’s I got into verification. I used verification to check the correctness of the code I wrote, but it was not the real value. I used verification to measure the efficiency and errors in the methods I developed. I used it to measure the error in the modeling I pursued. The direct measure of error and its comparison to alternatives was the reason I did it. It provides direct and immediate feedback on method development. These notions are absent from the verification narrative. Measuring and reducing errors is one of the core activities of science. It is the right way to conduct science.

Verification needs to embrace this narrative for it to have an impact.

How to Fix Verification?

“I ask you to believe nothing that you cannot verify for yourself.” — G.I. Gurdjieff

As noted above, the key to fixing verification is to keep both orders of accuracy and numerical accuracy in mind. This is true for both code and solution verification. The second part of the fix is expanding the utility of verification. Verification can measure the efficiency of methods. What I mean by efficiency requires a bit of explanation. The first thing is to define efficiency.

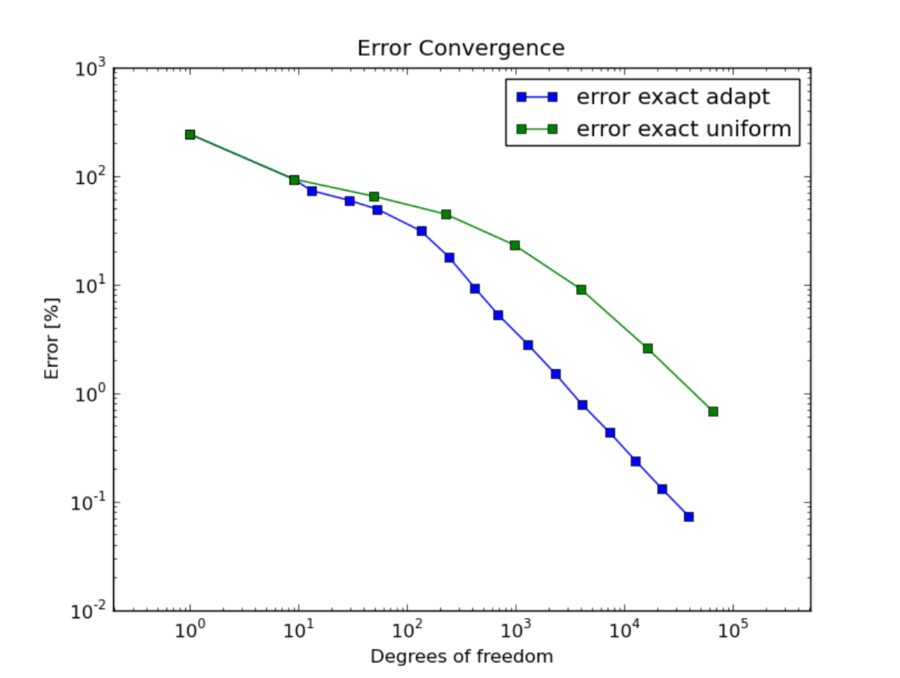

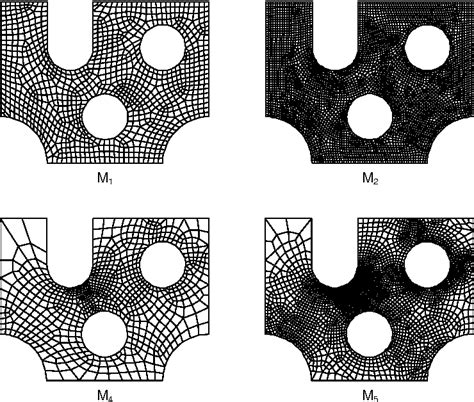

Simply put, efficiency is the amount of computational resources used to achieve a certain degree of accuracy. The resource would be defined by mesh size and number of time steps (degrees of freedom). The algorithm used to solve the problem would combine to define the amount of computer memory and a number of operations to use. Less is obviously better. Runtime for a code is a good proxy for this. Lower accuracy is also better. The convergence rate defines the relationship between the amount of effort and accuracy. The product of these two defines the efficiency. Lower is better for this composite metric.

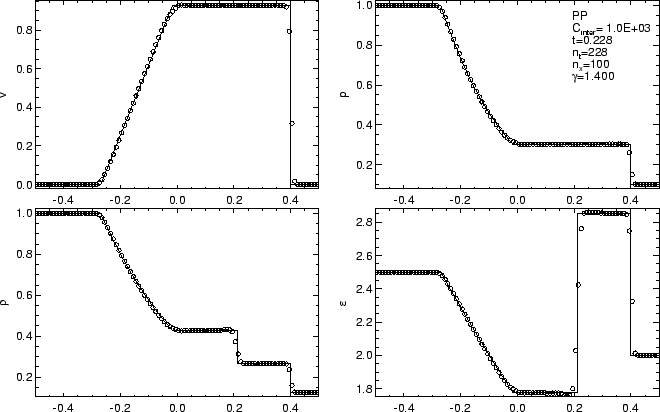

The first time I published something that exposed this was with Jeff Greenough. We compared two popular methods on a set of problems. One was the piecewise linear method using Colella’s improvements (fourth-order slopes). It was a second-order method. The second method is the very popular Weighted ENO method, which is fifth-oder in space and third-order in time. Both of these methods are designed to solve shock wave problems. One might think that the fifth-order method should win every time. This is true if you’re solving a problem where this accuracy matters. The issue is that all the applications of these methods are limited to first-order at best.

“Science replaces private prejudice with public, verifiable evidence.” — Richard Dawkins

This is where the accepted practice breaks down. When Gary Sod published his test problem and method comparison the only metric was runtime. Despite having an analytical solution, no error was measured. Results for the Sod shock tube problem are always qualitative. Early on, results were bad enough that qualitative mattered. Today all the results are qualitatively good and vastly better than nearly 50 years ago. This is accepted practice and implies that there is no difference quantitively. This is objectively false. At a given mesh resolution the error differences are significant. I showed this with Jeff for two “good” methods. As I will further amplify in what follows, at the lower convergence rates in shocks the level of error means vast differences in efficiency. This is true in 1-D and becomes massive in 3-D (really 2-D and 4-D when you add in time).

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.” — Richard P. Feynman

It turns out that the 5th-order WENO method is about six times as expensive as the 2nd-order PLM scheme. This was true of the desktop computers of 2004. It is close to the same now. The WENO method might have better computational intensity and have advantages on modern GPUs. What we discovered was that the second-order method produced half the error of the WENO method on simple problems (Sod’s shock tube). Thus the WENO method didn’t really pay off. At first-order convergence, this would mean that WENO would need about 24 times the effort to match the accuracy of PLM. For problems with more structure, the situation gets marginally better for WENO. In terms of efficiency, WENO never catches up with PLM, ever. As we will shortly see in 3-D the comparison is even worse. The cost of refining the mesh is much more costly and the accuracy advantage grows.

“Whatever you do will be insignificant, but it is very important that you do it.” ― Mahatma Gandhi

If This is Done, Verification’s Value Skyrockets

“The truth is rarely pure and never simple.” ― Oscar Wilde

Let’s consider a simple example to explain. Consider a method that is twice as expensive and twice as accurate as another method. The methods produce the same order of convergence. The order of convergence matters a great deal in determining efficiency. Consider three-dimensional time-dependent calculations. If the methods are fourth-order accuracy there is a break even. For any lower order of convergence the higher cost, more accurate method wins. The lower the order of convergence the greater the difference. For first-order the advantage is a factor of eight. By the time you drop to half-order convergence, the advantage grows to 128 times.

This example provides a powerful punchline to efficiency. If the order of accuracy is fixed, the level of accuracy makes a huge difference in efficiency. This points to the power of both algorithms and verification in demonstrating the metrics. It is absolutely essential for verification to amplify its impact on science.

“It’s easy to attack and destroy an act of creation. It’s a lot more difficult to perform one.” — Chuck Palahniuk

For problems solving hyperbolic PDEs, the convergence rates are well defined by theory. For the nonlinear compressible structures, the rate is defined as first-order. For linear waves (that Lax defined as linearly degenerate) the convergence rate is less than one. Thus the impact of accuracy is greater. In my experience, first-order accuracy is optimistic for practical application problems. Invariably the accuracy for practical problems codes are applied to are low order. Thus the accuracy for smooth problems where code verification is done has little relevance. This can show that the method is correct as derived, but not relate to the method’s use.

Code verification needs to focus on results that relate more directly to how methods are used practically. This is a challenge that needs focused research. Rather than a check done before use practically, code verification needs utility in the practical use. Today this is largely absent. This must change.

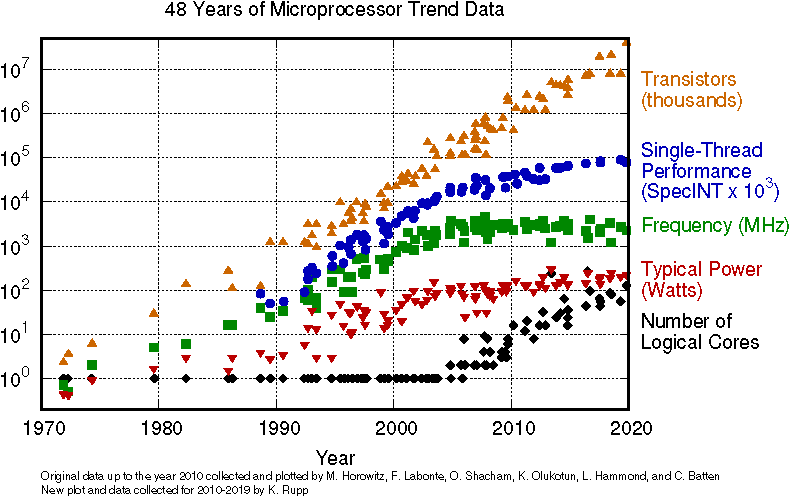

The other great use is the study of efficiency. With Moore’s law, dead and buried algorithms are the path to computational progress. In addition, the use of verification is needed for the expanding use of machine learning (ML, the techniques used for artificial intelligence). The greatest gaps for ML are the absence of theory to support verification. This is closely followed by a lack of accepted practice. Again, this supports algorithm development, which is the path to progress when computing and data are limited.

“The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing.” ― Albert Einstein

Greenough, J. A., and W. J. Rider. “A quantitative comparison of numerical methods for the compressible Euler equations: fifth-order WENO and piecewise-linear Godunov.” Journal of Computational Physics 196, no. 1 (2004): 259-281.

Rider, William J., Jeffrey A. Greenough, and James R. Kamm. “Accurate monotonicity-and extrema-preserving methods through adaptive nonlinear hybridizations.” Journal of Computational Physics 225, no. 2 (2007): 1827-1848.

Sod, Gary A. “A survey of several finite difference methods for systems of nonlinear hyperbolic conservation laws.” Journal of computational physics 27, no. 1 (1978): 1-31.

Colella, Phillip. “A direct Eulerian MUSCL scheme for gas dynamics.” SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing 6, no. 1 (1985): 104-117.

Jiang, Guang-Shan, and Chi-Wang Shu. “Efficient implementation of weighted ENO schemes.” Journal of computational physics 126, no. 1 (1996): 202-228.

Majda, Andrew, and Stanley Osher. “Propagation of error into regions of smoothness for accurate difference approximations to hyperbolic equations.” Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 30, no. 6 (1977): 671-705.

Banks, Jeffrey W., T. Aslam, and William J. Rider. “On sub-linear convergence for linearly degenerate waves in capturing schemes.” Journal of Computational Physics 227, no. 14 (2008): 6985-7002.