tl;dr

My career is drawing to a close. In looking back it is obvious that V&V played a crucial role. This was never intended, but rather an outgrowth of other goals. The main driver was numerical methods research. V&V assisted my research and became a secondary focus. Along the way, I encountered remarkable resistance to V&V. This is because V&V challenges expert-based gatekeeping. It replaces their judgment with evidence and metrics. The response from V&V should be transformed into something supported. This is a connection to the classical scientific method applied to computations.

How did V&V intersect my Career?

“What’s measured improves” ― Peter Drucker

I am at a point personally where reflection on the past is quite natural. My professional time at revered institutions is drawing to its natural end. At the same time, my father is nearing death in a slow painful decline. My scientific career seems to be undergoing a parallel decline. It feels like it is crawling to the grave ushered by a lack of vision and strategy everywhere. Science and research options are under siege. Rather than being repaired, the decline is accelerating. Our science and engineering is in deep decline. Money is the ruling principle while quality is ignored. The result is an expanding mediocrity.

I have seen a host of significant events during my career that shaped and framed the World. The Cold War ended at the beginning marked by the Berlin Wall coming down in 1989. Working closely within the institutions that oversee nuclear weapons means that politics matter. World events are never far from shaping the work while providing emphasis to our responsibility. The technical work and its quality have always mattered. The stakes are huge. Events today may dwarf anything else from the span of my career. We shall see. I hope this is hyperbolic, but I fear not.

The quality of our work matters. It should matter more greatly if you are working on nuclear weapons. It is what I believe with all my heart. I’ve always embraced this as a primal responsibility. Verification and validation (V&V) is fundamentally about quality. This is why I got involved with it. The core aspect of V&V is measurement and evidence. It is a way of seeing the details of your work without appealing to expert judgment. It was a reaction to science that is ruled by expert gatekeepers.

Being an expert gatekeeper is a great gig. Usually that gatekeeper role is earned through accomplishments. Once the gatekeeper makes progress they often stand in the way of it. The gatekeepers then oppose anyone who disagrees with them. The gatekeepers are often journal editors and common reviewers. Too often they use this position to act as resistance to change and new ideas. These days the gatekeeper role is supercharged by how funding flows. In a day of science contracting, the money has even more power to strangle progress.

“If you thought that science was certain – well, that is just an error on your part.” ― Richard P. Feynman

How V&V Became a Thing for Me?

When I got started in science I wasn’t doing V&V. I was doing a little V&V, but didn’t know it. Like most of you I copied what I saw in the literature. I found ideas that I gravitated towards and then wrote papers like those scientists. Their papers were the roadmap for how I did my work. You adopt the accepted practices of others Eventually as you find success, you start to adapt. I was fortunate enough to get to work with some big names on a large research project. The tendency of youth is to listen with rapt attention to the experts. Over time, I grew tired of simply trusting experts; I wanted to see the receipts. I trusted and respected their work and judgment, but I also needed evidence.

I started to see the cracks in their story. We were working with a couple of big names in computational physics and applied math. They were some of the scientists whose work I’d loved early on. Every couple of months they would travel to Los Alamos, or we’d travel to California for a project meeting. At these project meetings, we would be lectured on the “gospel” of the work. The issue was that the “gospel” changed a little bit each time. Eventually, I found that I needed to start doing everything myself. I needed to understand in detail of the “gospel”. I needed to see the evidence and verify what I heard.

“In questions of science, the authority of a thousand is not worth the humble reasoning of a single individual.” ― Galileo Galilei

This process was my real transformation into a V&V person. I created an independent implementation of everything including testing. I would reproduce tests done by others and then create my own tests. During this time I documented everything and began to adopt my basic mantra of code testing. This mantra is “always know the limits of your code, and how to break it.” This meant I understood where the code worked well and where it fell apart. It tells you where you can safely use the code.

It also tells you where the code falls apart. This is where you should do work to make things better. This should set the research agenda. I have always seen V&V as a route to progress instead of simply measuring capability. V&V should provide evidence to support expanding capabilities. Today, the route to progress via V&V is weak to non-existent.

One of the lessons I learned was the separation between robustness and accuracy tests. Progress happens through transitioning robustness tests into accuracy tests. A robustness test is basically “Can the code survive this and give any answer?”. The accuracy test is “Can the code give an accurate answer?” This was useful then and continues to be a maxim today. We should always be pushing this boundary outward. This is a mechanism to raise capability and do better.

“We learn wisdom from failure much more than from success. We often discover what will do, by finding out what will not do; and probably he who never made a mistake never made a discovery.” ―Samuel Smiles

The Problem with V&V

“There’s nothing quite as frightening as someone who knows they are right.” ― Michael Faraday

In short order, I moved to the Weapons Physics Division in Los Alamos (the infamous X-Division). X-Division was ramping up development efforts to support Stockpile Stewardship. This was the ASCI program. The initial ASCI program was basically writing codes for brand-new supercomputers. The focus was on the computers first and foremost, but the codes were needed to connect to nuclear weapons. The progress was the desire to change from existing codes denoted as “legacy” to new codes. New codes were mostly needed because of the change in computers. This was not about writing better codes, but just using better computers.

The rub was that the legacy codes were trusted by the people who designed weapons. They were the simulation tools used to design weapons in the era when we tested these more fully. This trust was essential to the results of the codes. The new codes were not trusted. To replace the legacy codes this trust needed to be built. One of the mechanisms to build trust was defined as the processes known as V&V. The key part of the trust was validation. Validation is the comparison of simulations with experimental data. The problem with V&V is a certain emotionless approach to science. V&V is process-heavy and emotionless.

“The measure of intelligence is the ability to change.” ― Albert Einstein

Why is the process a problem?

The trust and utility of the legacy codes were mostly granted by experts. The people who designed weapons were the experts! “Designers”. They took an adversarial view of V&V and its process. This process is not expert-based, but rational and metric-based. What I have seen over and over in my career is tension between experts and process. V&V is rejected because of its non-expert rational approach. It was also rather dry and dull compared to the magic of modeling nature on computers. My original love of modeling on the computer was the embrace of its “magic.” It’s fair to say this same magic enchanted others.

I believe that the biggest problem for V&V is the dullness and process. V&V needs to capture more of the magic of modeling. The whole attraction of science is the ability of theory to explain reality. Computation is the way to solve complex models. This is part of the very essence of the scientific method.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” ― Arthur C. Clarke

Seeing V&V Clearly

The V&V program was added to the ASCI program in 1998. It tried to fill the gap of rational process in adopting the new codes. This rational process was supposed to build trust in these codes. Implicitly this put it into direct conflict with the power of experts. Nonetheless, V&V grew and adapted to the environment gaining adherents and mindshare. We can see V&V growing in other parts of the computational modeling world. In broad terms, V&V grew in importance through the period of 2000-2010. After this, it peaked and now has started to decay in interest and importance. IMHO the reason for this is how dull and process-oriented V&V tends to be.

“Magic’s just science that we don’t understand yet.” ― Arthur C. Clarke

A big part of this decay is the continued resistance by experts to the process aspects of V&V. I experienced it directly with my own work. I had the journal editor tell me to “get that shit out of the paper.” While the resistance to V&V at Los Alamos was driven by designer culture. Resistance to V&V was far less at Sandia, but still present. Engineers love processes, but physicists don’t. Still, V&V gets in the middle of processes engineering analysts like. For example, both designers and analysts like to calibrate results.

“The most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers. The true dangerous thing is asking the wrong question.” ― Peter Drucker

They like to calibrate to data so that the simulations match experiments well. Worse yet they like to calibrate in ways that are not physically defensible. I’ve seen it over and over at Los Alamos (Livermore too) and Sandia. V&V stands in opposition to this. The common perspective is that V&V is accepted only so long as the results rubber stamp the designer-analyst views. If V&V is more critical, the V&V is attacked. The cumulative effect is for V&V to wane. We see V&V get hollowed out as a discipline.

“We may not yet know the right way to go, but we should at least stop going in the wrong direction.” ― Stefan Molyneux

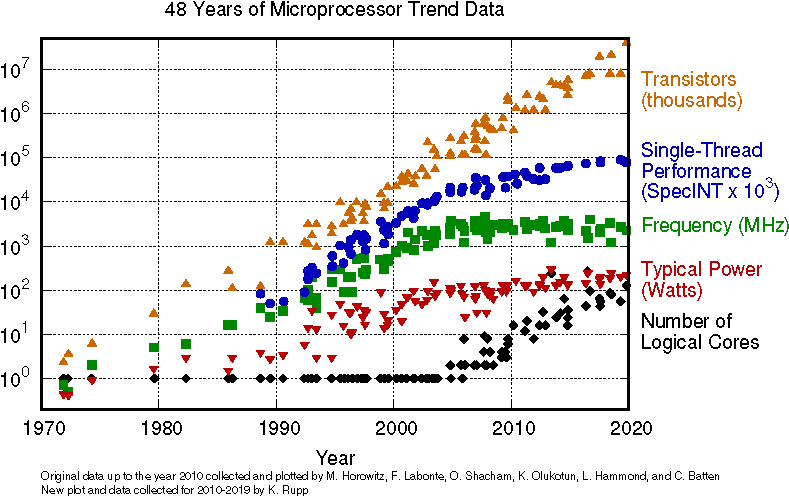

Another program added to V&V’s waning influence. The exascale program spun up around 2015. In many respects, this program was a redux of the original ASCI with a pure focus on supercomputing. Moore’s law was dying and the USA doubled down on supercomputing research. This program was far more computer-focused than ASCI ever was. It also didn’t try to replace legacy code but rather focused on rewriting the legacy codes. This reduced resistance. It also reduced progress. At least the original ASCI program wrote new codes, which energized modernizing codes. The exascale program lacked this virtue almost entirely. Hand-in-hand with the lack of modernization was a lack of V&V. There was no V&V focus in the exascale. The exascale view was simply that legacy methods are great and just need faster computers. To say this was intellectually shallow is an understatement of extreme degree.

“Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things.” ― Peter Drucker

My own theory was that V&V needed to move past its focus on process. V&V needed to be seen differently. My observation was that V&V was really just the scientific method for computational modeling. Verification is a confirmation of solving the theory correctly. Validation is the comparison of theory with experiments (or observation). The real desire here is to connect V&V to the magic of modeling. I wanted to make V&V more smoothly part of the things I love about science and attracted me to this career in the first place.

What Can We Learn?

“Men of science have made abundant mistakes of every kind; their knowledge has improved only because of their gradual abandonment of ancient errors, poor approximations, and premature conclusions.” ―George Sarton

If I look back across my career a few things stick out. One is how the programs rhyme with each other. The original ASCI program was much like the Exascale program. We learned how to fund a focus on big hardware purchases, but not the science parts. In almost every respect the Exascale program was worse than ASCI. It was much less science and much more computers. The way this happened reflects greatly on the forces undermining science more broadly. Computers get interest from Congress, but science and ideas don’t. That interest creates the funding needed, and everything runs on money. Money has become the measure of value for everything today.

“People who don’t take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year. People who do take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year.” ― Peter F. Drucker

The biggest lesson is how irrational science is. Emotions matter a lot in how things play out. We would like to think science is rational, but it’s not. Experts are gatekeepers and they like their power. Rational thought and process are the expert’s enemy. V&V is unrelentingly rational and process-based. Thus the expert will fight V&V. Experts also tend to be supremely confident. This is the uphill climb for V&V and the basis of its decline. The other piece of this is money and its power. Money is not terribly rational, and very emotional. It is the opposite of principle and rationality. This combines to sap the support for V&V.

None of this changes the need for V&V. The thing needed more than anything is a devotion to progress. V&V is a tool for measuring progress and optimizing the targeting of progress. The narrative of V&V as the scientific method also connects better with emotion. In the long run a better narrative and devotion to progress will rule and V&V should play its role.

“The best way to predict your future is to create it” ― Peter Drucker

“The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.” ― Arthur C. Clarke

Rider, W. J. “Approximate projection methods for incompressible flow: implementation, variants and robustness.” LANL UNCLASSIFIED REPORT LA-UR-94-2000, LOS ALAMOS NATIONAL LABORATORY. (1995).

Puckett, Elbridge Gerry, Ann S. Almgren, John B. Bell, Daniel L. Marcus, and William J. Rider. “A high-order projection method for tracking fluid interfaces in variable density incompressible flows.” Journal of computational physics 130, no. 2 (1997): 269-282.

Drikakis, Dimitris, and William Rider. High-resolution methods for incompressible and low-speed flows. Springer Science & Business Media, 2005.

Rider, William J., and Douglas B. Kothe. “Reconstructing volume tracking.” Journal of computational physics 141, no. 2 (1998): 112-152.

Greenough, J. A., and W. J. Rider. “A quantitative comparison of numerical methods for the compressible Euler equations: fifth-order WENO and piecewise-linear Godunov.” Journal of Computational Physics 196, no. 1 (2004): 259-281.

Rider, William J., Jeffrey A. Greenough, and James R. Kamm. “Accurate monotonicity-and extrema-preserving methods through adaptive nonlinear hybridizations.” Journal of Computational Physics 225, no. 2 (2007): 1827-1848.