tl;dr

One of the most damning aspects of the amazing results from LLMs are hallucinations. These are garbage answers delivered with complete confidence. Is this purely an artifact of LLMs, or more common than believed? I believe the answer is yes. Classical modeling and simulations using differential equations can deliver confident results without credibility. In the service of prediction this can be common. It is especially true when the models are crude or heavily calibrated then used to extrapolate away from data. The key to avoiding hallucination is the scientific method. For modeling and simulation this means verification and validation. This requires care and due diligence be applied in all cases of computed results.

“It’s the stupid questions that have some of the most surprising and interesting answers. Most people never think to ask the stupid questions.” ― Cory Doctorow

What are Hallucinations in LLMs?

In the last few years one of the most stunning technological breakthroughs are Large Language Models (LLMs, like ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini …). This breakthough has spurred visions of achieving artificial general intelligence soon. The answers to queries are generally complete and amazing. In many contexts we see LLMs replacing search as a means of information gathering. It is clearly one of the most important technologies for the future. There is the general view of LLMs broadly driving the economy of our future. There is a blemish on this forecast, hallucinations! Some of these complete confident answers are partial to complete bullshit.

“I believe in everything until it’s disproved. So I believe in fairies, the myths, dragons. It all exists, even if it’s in your mind. Who’s to say that dreams and nightmares aren’t as real as the here and now?” ― John Lennon

A LLM answers questions with unwavering confidence. Most of the time this is well grounded in objective facts. Unfortunately, this confidence is shown when results are false. Many examples show that LLMs will make up answers that sound great, but are lies. I asked ChatGPT to create a bio for me and it constructed a great sounding lie. It had me born in 1956 (1963) with a PhD in Math from UC Berkeley (Nuke Engineering, New Mexico). Other times I’ve asked to elaborate on experts in fields I know well. More than half the information is spot on, but a few experts are fictional.

“It was all completely serious, all completely hallucinated, all completely happy.” ― Jack Kerouac

The question is what would be better?

In my opinion the correct response is for the LLM to say, “I don’t know.” “That’s not something I can answer.” To a some serious extent this is starting to happen. LLMs will tell you they don’t have the ability to answer a questions. You also get responses like “this questions violate their rules.” We see the LLM community responding to this terrible problem. The current state is imperfect and hallucinations still happen. The community guidelines for LLMs are tantamount to censorship in many cases. That said, they are moving toward dealing with it.

Do classical computational models have the same issue?

Are they dealing with problems as they should?

Yes and no.

“I don’t paint dreams or nightmares, I paint my own reality.” ― Frida Kahlo

What would Hallucination be in Simulation?

Standard computational modeling is thought to be better because it is based on physical principles. We typically solve well defined and accepted governing equations. These equations are solved in a manner that is based on well known mathematical and computer science methods. This is correct, but it is not bulletproof. The reasons are multiple. One of the principal ways problems occur are the properties of the materials in a problem. A second way is the inclusion of physics not included in the governing equations (often called closure). A third major category is the construction of a problem in terms of initial and boundary conditions, or major assumptions. Numerical solutions can be under-resolved or produce spurious solutions. Mesh resolution can be suspect or inadequete for the numerical solution. The governing equations themselves include assumptions that may not be true or apply to the problem being solved..

“Why should you believe your eyes? You were given eyes to see with, not to believe with. Your eyes can see the mirage, the hallucination as easily as the actual scenery.” ― Ward Moore

The major weakness is the need for closure of the physical models used. This can take the form of constitutive relations for the media in the problem. It also applies to unresolved sales or physics in the problem. Constitutive relations usually abide by well defined principles quite often grounded in thermodynamics. They are the product of considering the nature of the material at scales under the simulation’s resolution. Almost always these scales are considered to be averaged/mean values. Thus the variability in the true solution is excluded from the problem. Large or divergent physics can emerge if the variability of materials is great at the scale of the simulation. Simple logic dictates that this variability grows larger as the resolution of a simulation becomes smaller.

A second connected piece of this problem is subscale physics not resolved, but dynamic. Turbulence modeling is the classical version of this. These models have significantly limited applicability and great shortcomings. This gets to the first category of assumption that needs to be taken in account. Is the model being used in a manner appropriate for it. Models also interact heavily with the numerical solution. The numerical effects/errors can often mimic the model’s physical effects. Numerical dissipation is the most common version of this, Turbulence is a nonlinear dissipative process, and numerical diffusion is often essential for stability. Surrounding all of this is the necessity of identifying unresolved physics to begin with.

Problems are defined by analysts in a truncated version of the universe. The interaction of a problem with that universe is defined by boundary conditions. The analyst also defines a starting point for a problem if it involves time evolution. Usually the state a problem starts from in a simple quiessiant version of reality. Typically it is far more homogeneous and simple that how reality is. The same goes to the boundary conditions. Each of these decisions influences the subsequent solution. In general these selections make problem less dynamically rich than reality.

Finally, we can choose the wrong governing equations based on assumptions about a problem. This can include choosing equations that leave out major physical effects. A compressible flow problem cannot be described by incompressible equations. Including radiation or multi-material effects is greatly complicating. Radiation transport has a heirarchy of equations ranging from diffusion to full transport. Each level of approximation involves vast assumptions and loss of fidelity. The more complete the equations are physically, the more expensive they are. There is great economy in choosing the proper level for modeling. The wrong choice can produce results that are not meaningful for a problem.

Classical simulations are distiguished by the use of numerical methods to solve equations. This produces solution to these equations far beyond where they are analytical. These numerical methods are grounded in powerful proven mathematics. Of course, the proven powerful math needs to be used and listened to. When it isn’t the solutions are suspect. Too often corners are cut and the theory is not applied. This can result in poorly resolved or spurious solutions. Marginal stability can threaten solutions. Numerical solutions can be non-converged or poorly resolved. Some of the biggest issues numerically are seen with solutions labeled as direct numerical simulation (DNS). Often the declaration of DNS means all doubt and scrutiny is short-circuited. This is dangerous because DNS is often treated as a substitute for experiments.

These five categories of modeling problems should convince the reader that mistakes are likely. These errors can be large and create extremely unphysical results. If the limitations or wrong assumptions are not acknowledged or known, the solution might be viewed as hallucinations. The solution may be presented with extreme confidence. It may seem to be impressive or use vast amounts of computing power. It may be presented as being predictive and an oracle. This may be far from the truth

The conclusion is that classical modeling can definitely hallucinate too! Holy shit! Houston, we have a problem!

“Software doesn’t eat the world, it enshittifies it” – Cory Doctorow

How to Detect Hallucinations?

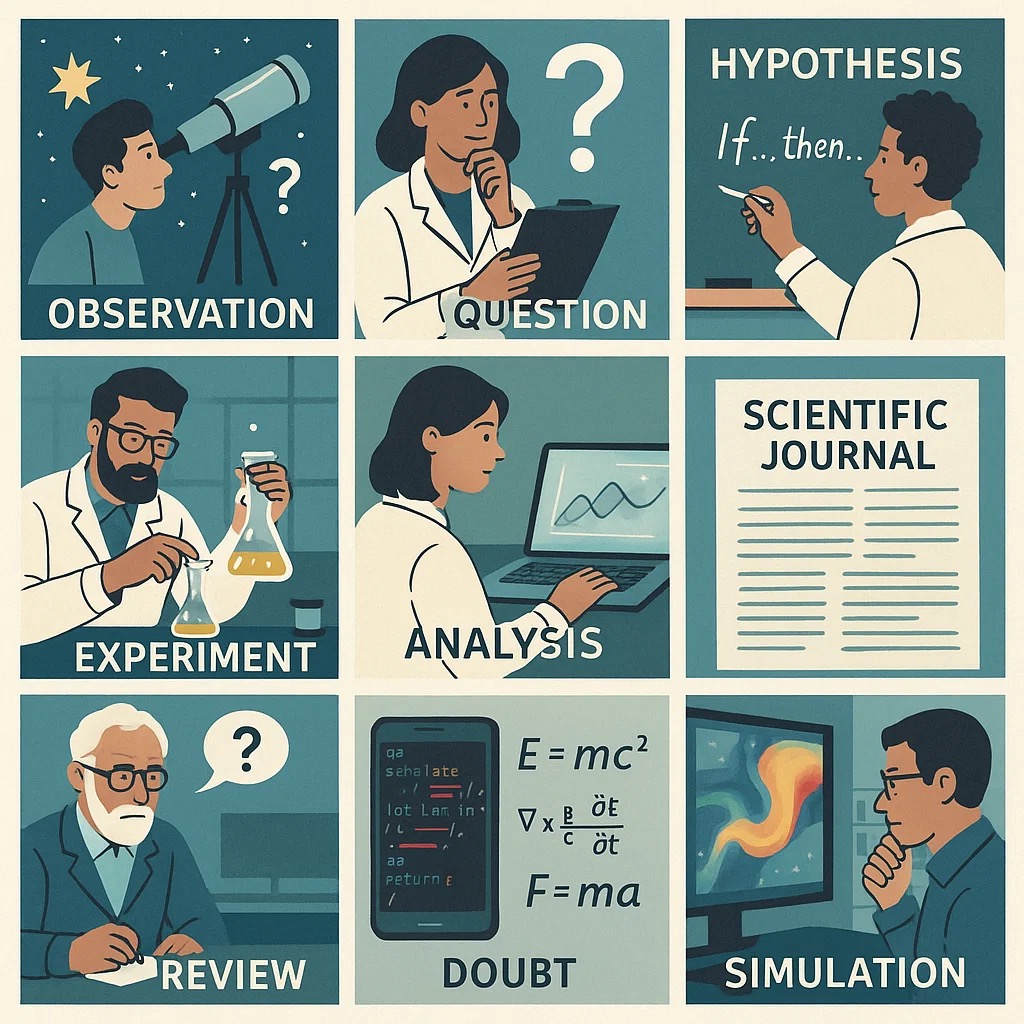

To find hallucinations, you need to look for them. There needs to be some active doubt applied to results given by the computer. Period.

The greatest risk is for computational results to be a priori believed. Doubt is a good thing. Much of the problem with hallucinating LLMs is the desire to give the user an answer no matter what. In the process of always giving an answer, bad answers are inevitable. Rather than reply that the answer can’t be given or is unreliable, the answer is given with confidence. In response to this problem LLMs have started to respond with caution.

“Would you mind repeating that? I’m afraid I might have lost my wits altogether and just hallucinated what I’ve longed to hear.” ― Jeaniene Frost

The same thing happens with classical simulations. In my experience the users of our codes want to always get an answer. If the codes succeed at this, some of the answers will be wrong. Solutions do not include any warnings or caveats. There are two routes to doing this. Technically the harder route is for the code itself to give warnings and caveats when used improperly. This would require the code’s authors to understand its limits. The other route is V&V. This requires the solutions to be examined carefully for credibility using standard techniques. Upon reflection, both routes go through the same steps, but applied systematically to the code’s solutions. The caveats are simply applied up front if the knowledge of limits is extensive. This can only be achieved through extensive V&V.

Some of these problems are inescapable. There is a way to minimize these hallucinations systematically. In a nutshell the scientific method offers the path for this. Again, we see verification and validation is the scientific method for computational simulation. It offers specific techniques and steps to guard against the problems outlined above. These steps offer an examination of the elements going into the solution. The suitability of the numerical solutions of the models and the models themsevles are examined critically. Detailed comparisons of solutions are made to experimental results. We see how well models produce solutions that model reality. Of course, this is expensive and time consuming. It is much easier to just accept solutions and confidently forge ahead. This is also horribly irresponsible.

“In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is a hallucinating idiot…for he sees what no one else does: things that, to everyone else, are not there.” ― Marshall McLuhan

How to Prevent Hallucinations?

To a great extent the problem of hallucinations cannot be prevented. The question is whether the users of software are subjected to it without caution. An alternative is for the users to be presented with a notice of caution with results. This does point to the need for caution to be exercised for all computational results. This is true for classical simulations and LLM results. All results should be treated with doubt and scrutiny.

V&V is the route to this scrutiny. For classical simulation V&V is a well-developed field, but often not practiced. For LLMs (AI/ML) V&V is nascent and growing, but immature. In both cases, V&V is difficult and time consuming. The biggest impediment is to V&V is a lack of willingness to do it. The users of all computational work would rather just blindly accept results than apply due diligence.

For the users it is about motivation and culture. Is the pressure on getting answers and moving to the next problem? or getting the right answer? My observation is that horizons are short-term and little energy motivates getting the right answer. With fewer experiments and tests to examine the solutions, the answer isn’t even checked. Where I’ve worked this is about nuclear weapons. You would think that due diligence would be a priority. Sadly it isn’t. I’m afraid we are fucked. How fucked? Time will tell.

“We’re all living through the enshittocene, a great enshittening, in which the services that matter to us, that we rely on, are turning into giant piles of shit.” – Cory Doctorow