tl;dr

Today’s world is ruled by extreme views and movements. These extremes are often a direct reaction to progress and change. People often prefer order and a well-defined direction. The current conservative backlash is a reaction. Much of it is based on the discomfort of social progress and economic disorder. In almost all things balance and moderation are a better path. The middle way leads to progress that sticks. Slow and deliberate change is accepted, while fast and precipitous change invites opposition. I will discuss how this plays out in both politics and science. In science, many elements contribute to the success of any field. These elements need to be present for success. Without the balance failure is the ultimate end. Peter Lax’s work was an example of this balance.

“All extremes of feeling are allied with madness.” ― Virginia Woolf

The Extremes Rule Today

It is not controversial to say that today’s world is dominated by extremism. What is a bit different is to point to the world of science for the same trend. The political world’s trends are illustrated vividly on screens across the World. We see the damage these extremes are doing in the USA, Russia, Israel-Gaza and everywhere online. One extreme will likely breed an equal and opposite reaction. Examples abound today such as over-regulation or political correctness in the USA. In each, true excesses are greeted with equal or greater excesses reversing them.

Science is not immune to these trends and excesses. I will detail below a couple of examples where no balance exists. One program is the exascale computing program which focuses on computational hardware. A second example is the support for AI. It is similarly hardware-focused. In both cases, we fail to recognize how the original success was catalyzed. The impacts, the need, and the route to progress are not seen clearly. We have programs that can only see computing hardware and fail to see the depth and nature of software.

In science software is a concrete instantiation of theory and mathematics. If theory and math are not supported, the software is limited in value. The progress desired by these efforts is effectively short-circuited. In computing, software has the lion’s share of the value. Hardware is necessary, but not where the largest advances have occurred. Yet the hardware is the most tangible and visible aspect of technology. In a mathematical parlance, the hardware is necessary, but not sufficient. We are advancing science in a clearly insufficient way.

“To put everything in balance is good, to put everything in harmony is better.” ― Victor Hugo

Balance in All Things

Extremism is simple. Reality is complex. Simple answers fall apart upon meeting the real World. This is true for politics and science. When extreme responses to problems are implemented, they invite an opposite extreme reaction. Lasting solutions require a subtle balance of perspectives and sources of progress. The best from each approach is necessary.

Take the issue of over-regulation as an example. Simply removing regulations invites the same forces that created the over-regulation in the first place. A far better approach is to pare back regulation thoughtfully. Careful identification of excess regulation build support for the project. The same thing applies to the freedom of speech and the excesses of “woke” or “cancel culture”. Those movements overstepped and created a powerful backlash. They were also responding to genuine societal problems of bigotry and oppressive hierarchy. A complete reversal is wrong and will create horrible excesses inviting a reverse backlash. Again, smaller changes that balance progress with genuine freedom would be lasting.

With those examples in mind, let us turn to science. In the computational world, we have seen a decade of excess. First with computing and pursuit of exascale high-performance computing. Next, in a starkly similar fashion artificial intelligence became an obsession. Current efforts to advance AI are focused on computational hardware. Other sources of progress are nearly ignored. In each case, there is serious hype along with an appealing simplicity in the sales pitch. In both cases, the simple approach short-changes progress and hampers broader success and long-term progress.

Let’s turn briefly to what a more balanced approach would look like.

At the core of any discussion of science should be the execution of the scientific method. This has two key parts working in harmony, theory and experiment (observation). Making these two approaches harmonize is the route to progress. Theory is usually expressed in mathematics and is most often solved on computers. If this theory describes what can be measured in the real world, we believe that we understand reality. Better yet, we can predict reality leading to engineering and control. Our technology is a direct result of this and much of our societal prosperity.

With this foundation, we can judge other scientific efforts. Take the recent Exascale program, which focused on creating faster supercomputers. The project focused on computing hardware and computer science while not supporting mathematics and theory vibrantly. This is predicated on some poor assumptions that theory is adequate (it isn’t) and our math is healthy. Both the theory and math need sustained attention. Examining history shows that math and theory have been to core of progress in computing. It is worse than this. The exascale focus came as Moore’s law ended. This was the exponential growth in computing power that held for almost a half-century starting in 1965. Its end was largely based on encountering physical barriers to progress. The route to increased computing value should shift to theory and math (i.e., algorithms). Yet, the focus was on hardware trying to breathe life into the dying Moore’s law. It is both inefficient and ultimately futile

Today, we see the same thing happening with AI. The focus is on computing hardware even though the growth in power is incremental. Meanwhile, the massive breakthrough in AI was enabled by algorithms. Limits on trust and correctness of AI are also grounded in the weakness of the underlying math for AI. A more vibrant and successful AI program would reduce hardware focus and increase math and algorithm support. This would serve both progress and societal needs. Yet we see the opposite.

We are failing to learn from our mistakes. The main reason is that we can’t call them mistakes. In every case, we are seeing excess breed more excess. Instead, we should balance and strike a middle way.

“Progress and motion are not synonymous.” ― Tim Fargo

A Couple Examples

The USA today is living through a set of extremes that are closely related. There is a burgeoning authoritarian oligarchy emerging as the central societal power. Much of the blame for this development is out-of-control capitalism without legal boundaries. There is virtually limitless wealth flowing to a small number of individuals. With this wealth, political power is amassing. A backlash is inevitable. The worst correction to this capitalist overreach would be a suspension of capitalism. Socialism seems to be the obvious cure. A mistake would be too much socialism. It would throw the baby up with the bathwater. A mixture of capitalism and socialism works best. A subtle balance of the two is needed. The most obvious societal example is health care where capitalism is a disaster. We have huge costs with worse outcomes.

In science, recent years have seen an overemphasis on computing hardware over all else. My comments apply to exascale and AI with near equality. Granted there are differences in the computing approach needed for each, but commonality is obvious. The value of that hardware is bound to software. Software’s value is bound to algorithms, which in turn are grounded in mathematics. That math can be discrete, information-related, or a theory of the physical world. This pipeline is the route to computing’s ability to transform our world and society. The answer is not to ignore hardware but to moderate it with other parts of the computing recipe for science. Without that balance the pipeline empties and becomes stale. That has probably already happened.

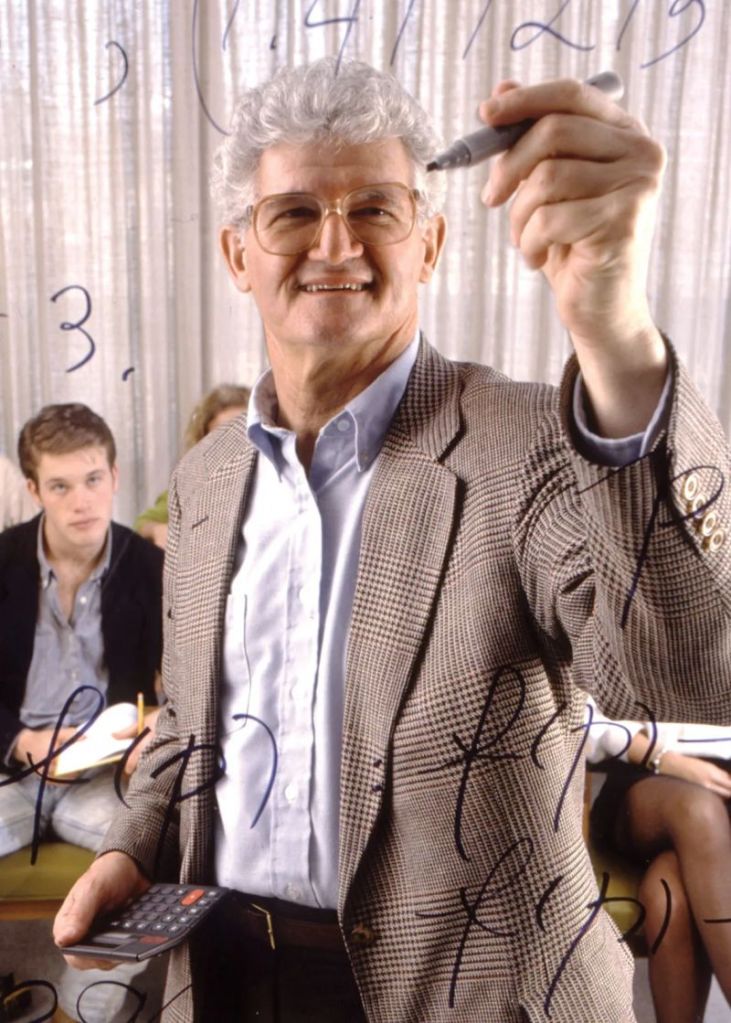

As I published this article, news of the death of Peter Lax arrived. I was buoyed by the prominence of his obituary in the New York Times. Peter’s work was essential to my career, and it is good to see him appropriately honored. Peter was the epitome of the creation of the value in the balance I’m discussing here. He was the consummate mathematical genius applying it to solve essential problems. While he contributed to applications of math, his work had the elegance and beauty of pure math. He also recognized the essential role of computing and computers. We would be wise to honor his contributions by following his path more closely. I’ve written about Peter and his work on several occasions here (links below).

“Keep in mind that there is in truth no central core theory of nonlinear partial differential equations, nor can there be. The sources of partial differential equations are so many – physical, probalistic, geometric etc. – that the subject is a confederation of diverse subareas, each studying different phenomena for different nonlinear partial differential equation by utterly different methods.”– Peter Lax

“To light a candle is to cast a shadow…” ― Ursula K. Le Guin