tl;dr

Uncertainty quantification (UQ) is ascending while verification & validation (V&V) is declining. UQ is largely done in silico and offers results that trivially harness modern parallel computing. UQ thus parallels the appeal of AI and easy computational results. It is also easily untethered to objective reality. V&V is a deeply technical and naturally critical practice. Verification is extremely technical. Validation is extremely difficult and time-consuming. Furthermore, V&V can be deeply procedural and regulatory. UQ has few of these difficulties although its techniques are quite technical. Unfortunately, UQ without V&V is not viable. In fact, UQ without the grounding of V&V is tailor-made for bullshit and hallucinations. The community needs to take a different path that mixes UQ with V&V, or disaster awaits.

“Doubt is an uncomfortable condition, but certainty is a ridiculous one.” ― Voltaire

UQ is Hot

If one looks at the topics of V&V and UQ, it is easy to see that UQ is a hot topic. It is vogue and garners great attention and support. Conversely, V&V is not. Before I give my sharp critique of UQ, I need to make something clear. UQ is extremely important and valuable. It is necessary. We need better techniques, codes, and methodologies to produce estimates of uncertainty. The study of uncertainty is guiding us to grapple with a key topic; how much we don’t know? This is difficult and uncomfortable work. Our emphasis on UQ is welcome. That said, this emphasis needs to be grounded in reality. I’ve spoken in the past about the danger of ignoring uncertainty. When an uncertainty is ignored it gets the default value of ZERO. In other words, ignored uncertainties are assigned the smallest possible value.

“The quest for certainty blocks the search for meaning. Uncertainty is the very condition to impel man to unfold his powers. ” ― Erich Fromm

As my last post discussed, the focus needs to be rational and balanced. When I observe the current conduct of UQ research, I see neither character. UQ takes on the mantle of the silver bullet. It is subject to the fallacy of the “free lunch” solutions. It seems easy and tailor-made for our currently computationally rich environment. It produces copious results without many of the complications of V&V. The practice of V&V is doubt based on deep technical analysis. It is uncomfortable and asks hard questions. Often questions that don’t have easy or available answers. UQ just gives answers with ease and it’s semi-automatic, in silico. You just need lots of computing power.

“I would rather have questions that can’t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.” ― Richard Feynman

This ease gets to the heart of the problem. UQ needs validation to connect it to objective reality. UQ needs verification to make sure the code is faithfully correct to the underlying math. Neither practice is so well established that it can be ignored. Yet, increasingly, they are being ignored. Experimental results are needed to challenge our surety. UQ has a natural appetite for computing thus our exascale computers lap it up. It is a natural way to create vast amounts of data. UQ attaches statistics naturally to modeling & simulation, a long-standing gap. Statistics connects to machine learning as it is the algorithmic extension of statistics. The mindset parallels the euphoria recently for AI.

For these reasons, UQ is a hot topic and attracting funding and attention today. Being in silico UQ becomes an easy way to get V&V-like results from ML/AI. What is missing? For the most part, UQ is done assuming V&V is done. For AI/ML this is a truly bad assumption. If you’re working in simulation you know that assumption is suspect. The basics of V&V are largely complete, but its practice is haphazard and poor generally. My observation is that computational work has regressed concerning V&V. Advances made in publishing and research standards have gone backward in recent years. Rather than V&V being completed and simply applied, it is dispised.

All of this equals a distinct danger for UQ. Without V&V UQ is simply an invitation for ModSim hallucinations akin to the problem AI has. Worse yet, it is an invitation to bullshit the consumers of simulation results. Answers can be given knowing they have a tenuous connection to reality. It is a recipe to fool ourselves with false confidence.

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.” ― Richard P. Feynman

AI/ML Feel Like UQ and Surrogates are Dangerous

One of the big takeaways from the problems with UQ is the appeal of its in-silico nature. This paves the way to easy results. Once you have a model and working simulation UQ is like falling off a log. You just need lots of computing power and patience. Yes, it can be improved and made more accurate and efficient. Nonetheless, UQ asks no real questions about the results. Turn the crank and the results fall out (unless it triggers a problem with the code). You can easily get results although doing this efficiently is a research topic. Nonetheless being in silico removes most of the barriers. Better yet, it uses the absolute fuck out of supercomputers. You can so fill a machine up with calculations. You get results galore.

If one is paying attention to the computational landscape you should be experiencing deja vu. AI is some exciting in-silico shit that uses the fuck out of the hardware. Better yet, UQ is an exciting thing to do with AI (or machine learning really). Even better you can use AI/ML to make UQ more efficient. We can use computational models and results to train ML models that can cheaply evaluate uncertainty. All those super-fast computers can generate a shitload of data. These are called surrogates and they are all the rage. Now you don’t have to run the expensive model anymore; you just train the surrogate and evaluate the fuck out of it on the cheap. Generally machine learning is poor at extrapolating, and in high dimensions (UQ is very high dimensional) you are always extrapolating. You better understand what you’re doing and machine learning isn’t well understood.

What could possibly go wrong?

If the model you trained the surrogate on has weak V&V, a lot can go wrong. You are basically evaluating bullshit squared. Validation is essential to establishing how good a model is. You should produce a model form error that expresses how well the computational model works. The model also has numerical errors due to the finite representation of the computation. I can honestly say that I’ve never seen either of these fundamental errors associated with a surrogate. Nonetheless, surrogates are being developed to power UQ all over the place. It’s not a bad idea, but these basic V&V steps should be an intrinsic part of this. To me, the state of affairs says more about the rot at the heart of the field. We have lost the ability to seriously question computed results. V&V is a vehicle for asking these questions. These questions are too uncomfortable to be confronted with.

V&V is Hard; Too Hard?

I’ve worked at two NNSA Labs (Los Alamos and Sandia) in the NNSA V&V program. So I know where the bodies are buried. I’ve been part of some of the achievements of the program and where it has failed. I was at Los Alamos when V&V arrived. It was like pulling teeth to make progress. I still remember the original response to validation as a focus, “Every calculation a designer does is all the validation we need!” The Los Alamos weapons designers wanted hegemonic control over any assessment of simulation quality. Code developers, computer scientists, and any non-designer were deemed incompetent to assess quality. To say it was an uphill battle was an understatement. Nonetheless, progress was made, albeit mildly.

V&V fared better at Sandia. In many ways, the original composition of the program had its intellectual base at Sandia. This explained a lot of the foundational resistance from the physics labs. It also gets too much of a problem with V&V today. Its focus on the credibility of simulations makes it very process-oriented and regulatory. As such it is eye-rollingly boring and generates hate. This character was the focus of the opposition at Los Alamos (Livermore too). V&V has too much of an “I told you so” vibe. No one likes this and V&V starts to get ignored because it just delivers bad news. Put differently, V&V asks lots of questions but generates few answers.

Since budgets are tight and experiments are scarce, the problems grow. We start to demand calculations to have close agreement with available data. Early predictions typically don’t meet standards. By and large, simulations have a lot of numerical error even on the fastest computers. The cure for this is an ex-post-facto calibration of the model to match experiments better. The problem is that this then short-circuits validation. Basically, there is little or no actual validation. Almost everything is calibrated unless the simulation is extremely easy. The model has a fixed grid, so there’s no verification either. Verification is bad news without a viable current solution. What you can do with such a model is lots of UQ. Thus UQ becomes the results for the entire V&V program.

To really see this clearly we need to look West to Livermore.

What does UQ mean without V&V?

I will say up front that I’m going to give Livermore’s V&V program a hard time, but first, they need big kudos. The practice of computational physics and science at Livermore is truly first-rate. They have eclipsed both Sandia and Los Alamos in these areas. They are exceptional code developers and use modern supercomputers with immense skill. They are a juggernaut in computing.

By almost any objective measure Livermore’s V&V program produced the most important product of the entire ASC program, common models. Livermore has a track record of telling Washington one thing and doing something a bit different. Even better, this something different is something better. Not just a little better, but a lot better. Common models are the archetypical example of this. Back in the 1990’s, there was this metrics project looking at validating codes. Not a terrible idea at all. In a real sense, Livermore did do the metrics in the end but took a different smarter path to them.

What Livermore scientists created instead was a library of common models that combined experimental data, computational models, and auxiliary experiments. The data was accumulated across many different experiments and connected into a self-consistent set of models. It is an incredible product. It has been repeated at Livermore and then at Los Alamos too across the application space. I will note that Sandia hasn’t created this, but that’s another story of differences in Lab culture. These suites of common models are utterly transformative to the program. It is a massive achievement. Good thing too because the rest of V&V there is far less stellar.

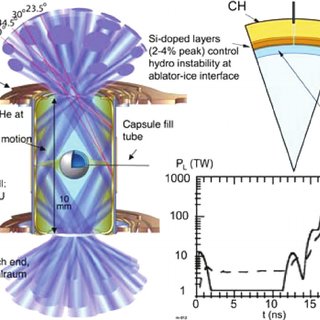

What Livermore has created instead is lots of UQ tools and practice. The common models are great for UQ too. One of the first things you notice about Livermore’s V&V is the lack of V&V. Verification leads the way in being ignored. The reasons are subtle and cultural. Key to this is an important observation about Livermore’s identity as the fusion lab. Achieving fusion is the core cultural imperative. Recently, Livermore has achieved a breakthrough at the National Ignition Facility (NIF). This was “breakeven” in terms of energy. They got more fusion energy out than laser energy in for some NIF experiments (all depends on where you draw the control volume!).

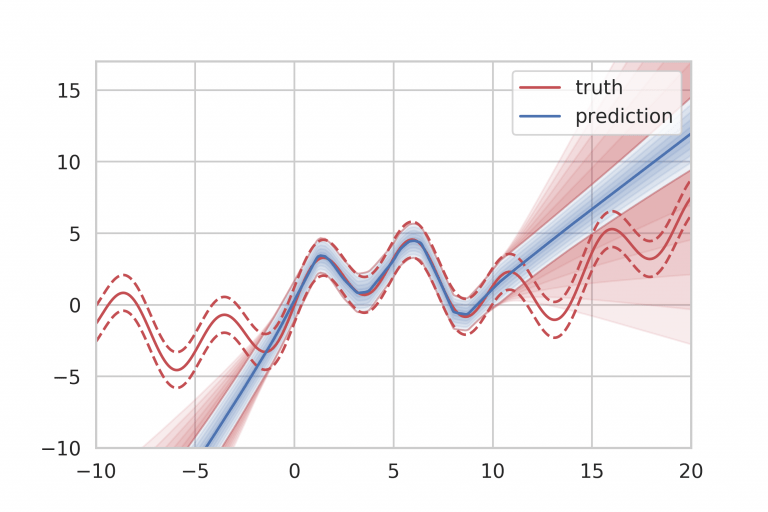

The NIF program also has the archetypical example of UQ gone wrong. Early on in the NIF program, there was a study of fusion capsule design and results. They looked at a large span of uncertainties in the modeling of NIF and NIF capsules. It was an impressive display of the UQ tools developed by Livermore, their codes, and computers. At the end of the study, they created an immensely detailed and carefully studied prediction of outcomes for the upcoming experiments. This was presented as a probability distribution function of capsule yield. It covered an order of magnitude from 900 kJ to 9 MJ of yield. When they started to conduct experiments, the results were not even in the range predicted by about a factor of three on the low side. The problems and dangers of UQ were laid bare.

“The mistake is thinking that there can be an antidote to the uncertainty.” ― David Levithan

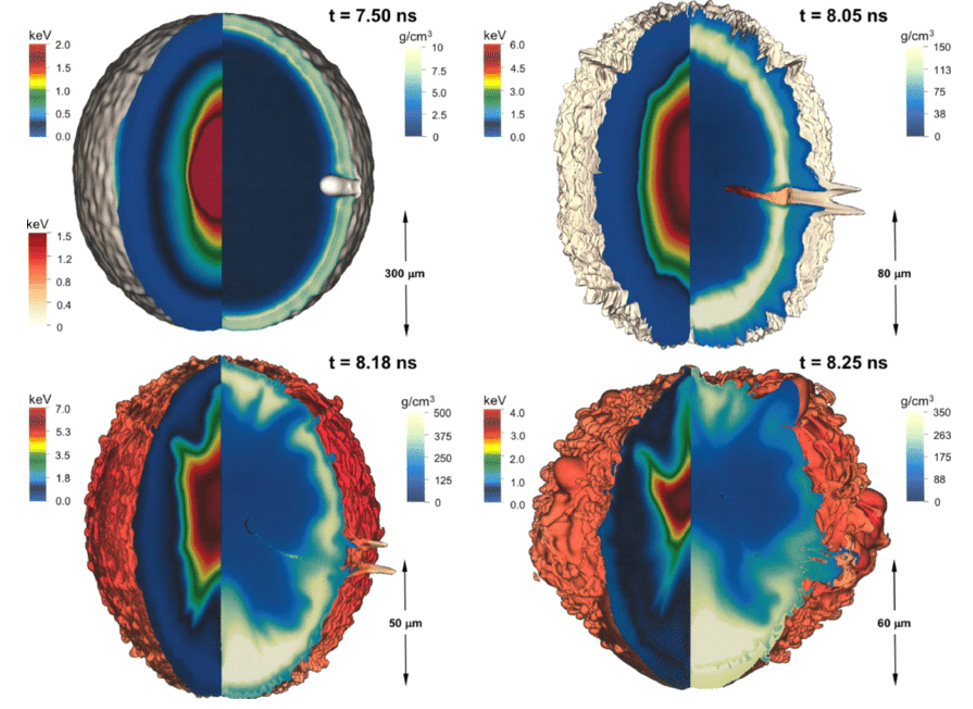

If you want to achieve fusion the key is really hot and dense matter. The way to get this hot and dense matter is to adiabatically compress the living fuck out of material. To do this there is a belief in numerical Lagrangian hydrodynamics with numerical viscosity turned off in adiabatic regions gives good results. The methods they use are classical and oppositional to modern shock-capturing methods. To compute shocks properly needs dissipation and conservation. The ugly reality is that hydrodynamic mixing (excessively non-adiabatic dissipative and ubiquitous) is an anathema to Lagrangian methods. Codes need to leave the Lagrangian frame of reference and remap. Conserving energy is one considerable difficulty.

Thus, the methods favored at Livermore cannot successfully pass verification tests for strong shocks. Thus, verification results are not shown. For simple verification problems there is a technique to get good answers. The problem is that the method doesn’t work on applied problems. Thus, good verification results for shocks don’t apply to key cases where the codes are used. They know the results will be bad because they are following the fusion mantra. Failure to recognize the consequences of bad code verification results is magical thinking. Nothing induces magical thinking like a cultural perspective that values one thing over all others. This is a form of extremism discussed in the last blog post.

There are two unfortunate side effects. The first obvious one is the failure to pursue numerical methods that simultaneously preserve adiabats and compute shocks correctly. This is a serious challenge for computational physics. It should be vigorously pursued and developed by the program. It also represents a question asked by verification without an easy answer. The second side effect is a complete commitment to UQ as the vehicle for V&V where answers are given and questions aren’t asked. At least not really hard questions.

UQ is left and becomes the focus. It is much better for results and for giving answers. If those answers don’t need to be correct, we have an easy “success.”

“It doesn’t matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn’t matter how smart you are. If it doesn’t agree with experiment, it’s wrong.” ― Richard P. Feynman

A Better Path Forward

Let’s be crystal clear about the UQ work at Livermore, it is very good. Their tools are incredible. In a purely in silico way the work is absolutely world-class. The problems with the UQ results are all related to gaps in verification and validation. The numerical results are suspect and generally under-resolved. The validation of the models is lacking. This gap is chiefly from the lack of acknowledgment of calibrations. Calibration of results is essential for useful simulations of challenging systems. NIF capsules are one obvious example. Global climate models are another. We need to choose a better way to focus our work and use UQ properly.

“Science is what we have learned about how to keep from fooling ourselves.” ― Richard Feynman

My first key recommendation is to ground validation with calibrated models. There needs to be a clear separation of what is validated and what is calibrated. One of the big parts of the calibration is the finite mesh resolution of the models. Thus the calibrations mix both model form error and numerical error. All of this needs to be sorted out and clarified. In many cases, these are the dominant uncertainties in simulations. They swallow and neutralize the UQ we spend our attention on. This is the most difficult problem we are NOT solving today. It is one of the questions raised by V&V that we need to answer.

“Maturity, one discovers, has everything to do with the acceptance of ‘not knowing.” ― Mark Z. Danielewski

The practice of verification is in crisis. The lack of meaningful estimates of numerical error in our most important calculation is appalling. Code verification has become a niche activity without any priority. Code verification for finding bugs is about as important as taking your receipt with you from the grocery store. Nice to have, but it’s very rarely checked by anybody. When it is checked, it’s because you’re probably doing something a little sketchy. Code verification is key to code and model quality. It needs to expand in scope and utility. It is also the recipe for improved codes. Our codes and numerical methods need to progress, They must continue to get better. The challenge of correctly computing strong shocks and adiabats is but one. There are many others that matter. We are still far from meeting our modeling and simulation needs.

“What I cannot create, I do not understand.” ― Richard P. Feynman

Ultimately we need to recognize how V&V is a partner to science. It asks key questions of our computational science. It is then the goal to meet these questions with a genuine search for answers. V&V also provides evidence of how well the question is answered, This question-and-answer cycle is how science must work. Without the cycle, progress stalls, and the hopes of the future are put at risk.

“If you thought that science was certain – well, that is just an error on your part.” ― Richard P. Feynman