TL;DR

The standard narrative for code verification is demonstrating correctness and finding bugs. While this is true, it also sells verification as a practice that is wildly short. Code verification has a myriad of other uses, foremost the assessment of accuracy without ambiguity. It can also define features of code, such as adherence to invariants in solutions. Perhaps, most compellingly, it can define the limits of a code-method and research needs to advance capability.

“Details matter, it’s worth waiting to get it right.” ― Steve Jobs

What People Think It Does

There is a standard accepted narrative for code verification. It is a technical process of determining that a code is correct. A lack of correctness is caused by bugs in the code that implements a method. It is supported by two engineering society standards written by AIAA (aerospace engineers) and ASME (mechanical engineers). The DOE-NNSA’s computing program, ASC, has adopted the same definition. It is important for the quality of code, but it is drifting to obscurity and a lack of any priority. (Note the IEEE has a different definition for verification, leading to widespread confusion.)

The definition has several really big issues that I will discuss below. Firstly, the definition is too limited and arguably wrong in emphasis. Secondly, it means that most of the scientific community doesn’t give a shit about it. It is boring and not a priority. It plays a tiny role in research. Thirdly, it sells the entire practice short by a huge degree. Code verification can do many important things that are currently overlooked and valuable. Basically there are a bunch of reasons to give a fuck about it. We need to stop undermining the practice.

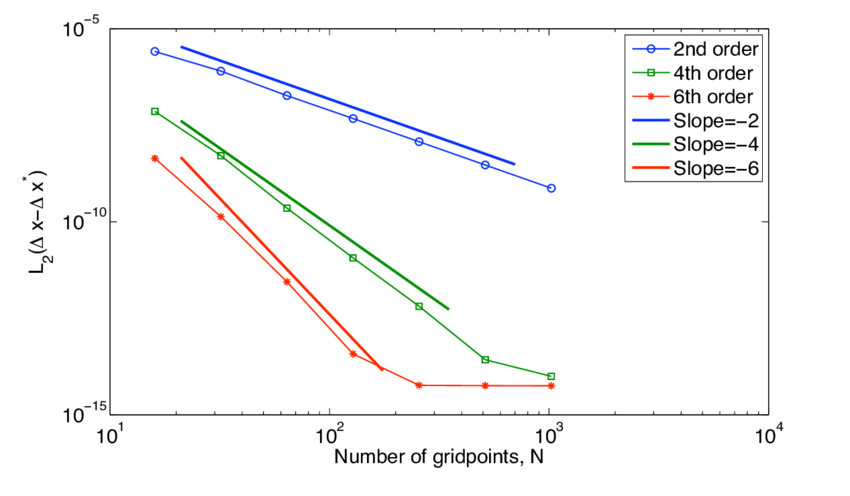

The basics of code verification are simple. A method for solving differential equations has an ideal order of accuracy. Code verification compares the solution by the code with an analytical solution over a sequence of meshes. If the order of accuracy observed matches the theory, the code is correct. If it does not, the code has an error either in the code or in the construction of the method. One of the key reasons we solve differential equations with computers is the dearth of analytical solutions. For most circumstances of practical interest, there is no analytical solution, nor circumstances that match the order of accuracy of method design.

One of the answers to the dearth of analytical solutions is the practice of the method of manufactured solutions (MMS). It is a simple idea in concept where an analytical right-hand side is added to equations to force a solution. The forced solution is known and ideal. Using this practice, the code can be studied. The technique has several practical problems that should be acknowledged. First is the complexity of these right-hand sides is often extreme, and the source term must be added to the code. It makes the code different than the code used to solve practical problems in this key way. Secondly, the MMS problems are wildly unrealistic. Generally speaking, the solutions with MMS are dramatically unlike any realistic solution.

MMS simply expands the distance of code verification for the code’s actual use. All this does is amplify the degree to which code users disdain code verification. The whole practice is almost constructed to destroy the importance of code verification. It’s also pretty much dull as dirt. Unless you just love math (some of us do), MMS isn’t exciting. We need to move forward towards practices people give a shit about. I’m going to start by naming a few.

“If you thought that science was certain – well, that is just an error on your part.” ― Richard P. Feynman

It Can Measure Accuracy

“I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something.” ― Richard P. Feynman

I’ve already taken a stab at this topic, noting that code verification needs are refresh:

Here, I will just recap the first and most obvious overlooked benefit, measuring the meaningful accuracy of codes. Code verification’s standard definition concentrates on order of accuracy as the key metric. Practical solutions with code rarely achieve the design order of accuracy. This further undermines code verification as significant. Most practical solutions give first-order accuracy (or lower). The second metric from verification is error, and with analytical solutions, you can get precise errors from the code. The second thing to focus on is the efficiency of a code that connects directly.

A practical measure of code efficiency is accuracy per unit effort. Both of these can be measured with code verification. One can get the precise errors by solving a problem with an analytical solution. By simultaneously measuring the cost of the solution, the efficiency can be assessed. For practical use, this measurement means far more than finding bugs via standard code verification. Users simply assume codes are bug-free and discount the importance of this. They don’t actually care much because they can’t see it. Yes, this is dysfunctional, but it is the objective reality.

The measurement and study of code accuracy is the most straightforward extension of the nominal dull as dirt practice. There’s so much more as we shall see..

It Can Test Symmetries

“Symmetry is what we see at a glance; based on the fact that there is no reason for any difference…” ― Blaise Pascal

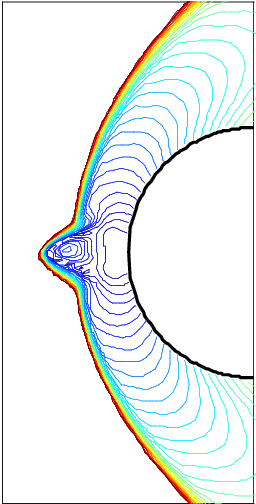

One of the most important aspect of many physical laws are symmetries. These are often preserved by ideal versions of these laws (like the differential equations code’s solve). Many of these symmetries are solved inexactly by methods in codes. Some of these symmetries are simple, like preservation of geometric symmetry, such as cylindrical or spherical flows. This can give rise to simple measures that accompany classical analytical solutions. The symmetry measure can augment the standard verification approach with additional value. In some applications, the symmetry is of extreme importance.

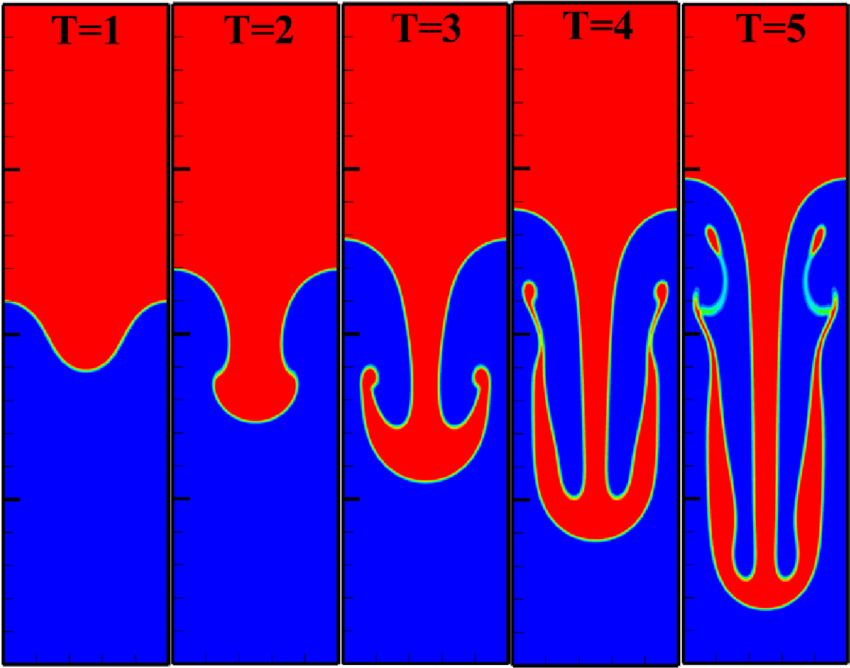

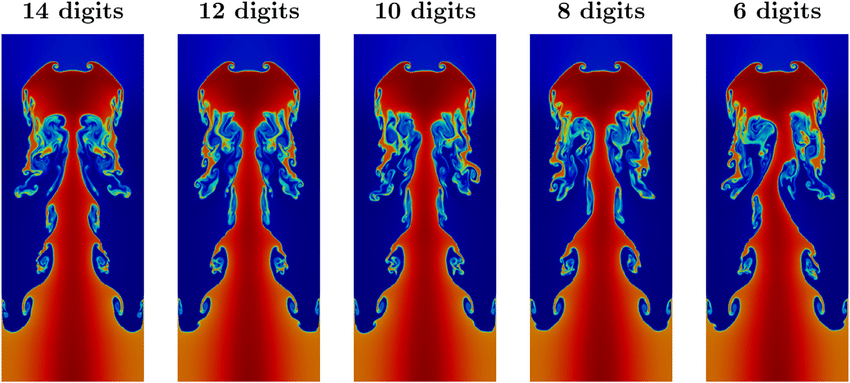

There are many more problems that can be examined for symmetry without having an analytical solution. One can create all sorts of problems with symmetries built into the solution. A good example of this is a Rayleigh-Taylor instability problem with a symmetry plane where left-right symmetry is desired. The solution can be examined as a function of time. This is an instability, and the challenge to symmetry grows over time. As the problem evolves forward the lack of symmetry becomes more difficult to control. It makes the test extreme if run for very long times. Symmetry problems also tend to grow as the mesh is refined.

It is a problem I used over 30 years ago to learn how to preserve stability. It was an incompressible variable-density code. I found the symmetry could be threatened by two main parts of the code: the details of upwinding in the discretization, and numerical linear algebra. I found that the pressure solve needed to be symmetric as well. I had to modify each part of the algorithm to get my desired result. The upwinding had to be changed to avoid any asymmetry concerning the sign of upwinding. This sort of testing and improvement is the hallmark of high-quality code and algorithms. Too little of this sort of work is taking place today.

It Can Find “Features”

“A clever person solves a problem. A wise person avoids it.” ― Albert Einstein

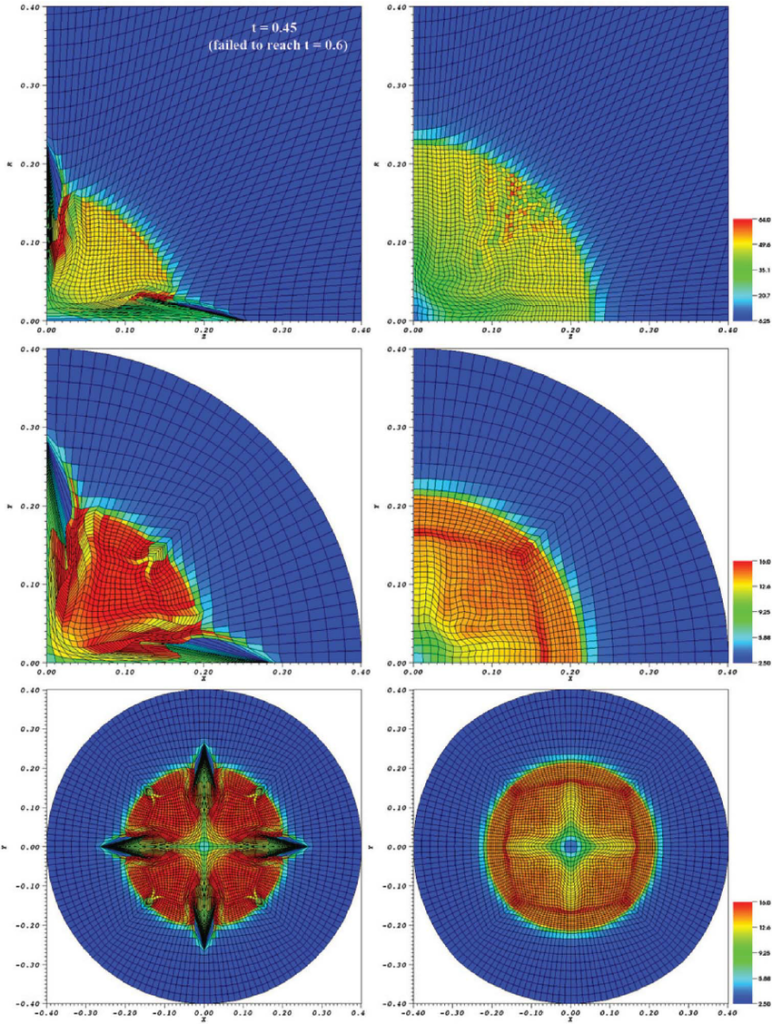

The usual mantra for code verification is lack of convergence means a bug. This is not true. This is a very naive and limiting perspective. For codes that compute the solution to shock waves (and weak solutions), correct solutions require conservation and entropy conditions. Methods and codes do not always adhere to these conditions. In those cases, a “perfect” bug-free code will produce incorrect solutions. They will converge on a solution, just converge to the wrong solution. The wrong solution is a feature of the method and code. These wrong solutions are revealed easily by extreme solutions with very strong shocks.

These features are easily fixed by using different methods. The problem is that the codes with these features are the product of decades of investment and reflect deeply held cultural norms. Respect for verification is acutely not one of those norms. My experience is that users of these codes make all sorts of excuses for this feature. Mostly, this sounds like the systematic devaluing of the verification work and excuses for ignoring the problem. Usually, they start talking about how important the practical work the code does. They fail to see how damning the results of failing to solve these problems. Frankly, it is a pathetic and unethical stand. I’ve seen this over and over at multiple Labs.

Before I leave this topic, I will get to another example of a code feature. This has a similarity to the symmetry examination. Shock codes can often have a shock instability with a funky name, the carbuncle phenomenon. This is where you have a shock aligned with a grid, and the shock becomes non-aligned and unstable. This feature is a direct result of properly implemented methods. It is subtle and difficult to detect. For a large class of problems, it is a fatal flaw. Fixing the problem requires some relatively simple but detailed changes to the code. It also shows up in strong shock problems like Noh and Sedov. At the symmetry axes, the shocks can lose stability and show anomalous jetting.

This gets to the last category of code verification benefits, determining a code’s limits and a research agenda.

“What I cannot create, I do not understand.” ― Richard P. Feynman

It Can Find Your Limits and Define Research

If you are doing code verification correctly, the results will show you a couple of key things: what the limits of the code are, and where research is needed. My philosophy of code verification is to beat the shit out of a code. Find problems that break the code. The better the code is, the harder it is to break. The way you break the code is to define harder problems with more extreme conditions. One needs to do research to get to the correct convergent solutions.

Where the code breaks is a great place to focus on research. Moving the horizons of capability outward can define an excellent and useful research agenda. In a broad sense, the identification of negative features is a good practice (the previous section). Another example of this is extreme expansion waves approaching vacuum conditions. In the past, I have found that most usual shock methods cannot solve this problem well. Solutions are either non-convergent or so poorly convergent as to render the code useless.

This problem is not altogether surprising given the emphasis on methods. Computing shock waves has been the priority for decades. When a method cannot compute a shock properly, the issues are more obvious. There is a clear lack of convergence in some cases or catastrophic instability. Expansion waves are smooth, offering less challenge, but they are also dissipation-free and nonlinear. Methods focused on shocks shouldn’t necessarily solve them well (and don’t when they’re strong enough).

I’ll close by another related challenge. The use of methods that are not conservative is driven by the desire to compute adiabatic flows. For some endeavors like fusion, adiabatic mechanisms are essential. Conservative methods necessary for shocks often (or generally) cannot compute adiabatic flows well. A good research agenda might be finding the methods that can achieve conservations, preserving adiabatic flows, and strong shock waves. A wide range of challenging verification test problems is absolutely essential for success.

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.” ― Richard P. Feynman