“We don’t want to change. Every change is a menace to stability.” ― Aldous Huxley

There is a problem with finishing up a blog post on a vacation day, you forget one of the nice ideas you wanted to share. So here is a brief addendum to what I wrote yesterday.

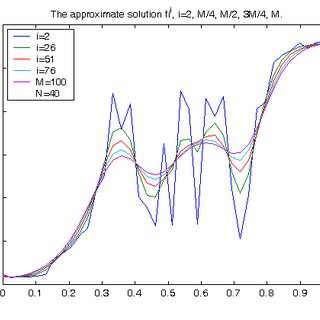

Here is a little addition to my last post here. It is another type of test I’ve tried, but also seldom seen documented. A standard threat to numerical methods is violating stability conditions. Stability is one of the most important numerical concepts. It is a prerequisite for convergence and is usually implicitly assumed. What is not usually tested is an active test of the transition of a calculation to instability. The simplest way to do this is to violate the time step size determined for instability.

The tests are simple. Basically, run the code with time steps over the stability limit and observe how sharp the limits are in practice. It also does a good job of documenting what an instability actually looks like when it appears. If the limit is not sharp, it might indicate an opportunity to improve the code by sharpening a bound. One could also examine if the lack of stability inhibits convergence, too. This would just be cases where the instability is mild and not catastrophic.

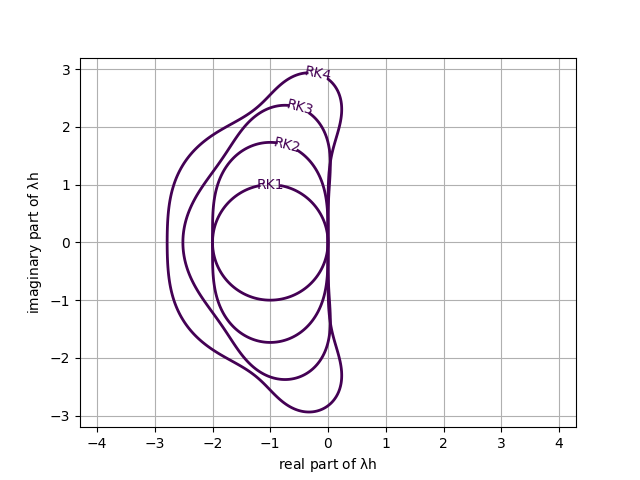

I did this once in my paper with Jeff Greenough, comparing a couple of methods for computing shocks. In this case, the test was the difference between linear and nonlinear stability for a Runge-Kutta integrator. The linear limit is far more generous than the nonlinear limit (by about a factor of three!). The accuracy of the method is significantly impacted at the limit of each of the two conditions. For shock problems, the difference in solutions and accuracy is much stronger. It also impacts the efficiency of the method a great deal.

Greenough, J. A., and W. J. Rider. “A quantitative comparison of numerical methods for the compressible Euler equations: fifth-order WENO and piecewise-linear Godunov.” Journal of Computational Physics 196, no. 1 (2004): 259-281.