Prolog

The irony of this post is that the circumstances of my departure are a perfect conclusion. It was entirely consistent with the history of V&V and its present state. If peer review is unserious and not taken seriously, V&V is useless. To use AI well and safely, V&V is essential, yet it is absent in plans and programs. One of the things I’ve done since starting the blog is use the writing to help think about a talk I would give. T This is a throwback to that approach. I gave this talk on my last working day at Sandia, but wrote this ahead of that. Enjoy!

tl;dr

V&V has been a central pursuit of my professional career. The origins of V&V came from highly regulated nuclear pursuits such as waste and reactors. These rely upon modeling for understanding. Grafting these ideas onto Stockpile Stewardship is logical, but not immediately recognized. V&V was part of a redirect of the program toward balance and building capability. This balance and focus on capability has faded away. The program is all about supercomputing as it was at the beginning. The same basic recipe is being proposed for the pursuit of AI. In both cases, V&V is virtually absent, and the balance is non-existent. Our national programs are destined to fail through ignorance and hubris.

There is a risk that we will become a cargo culture around things like AI, but also our codes. This is the worship of a technology without any real understanding. The defense against this is doing hard peer review and critical assessments of capability. New expanded capability should be continuously sought. Instead, we see technology delivered for use from outside or the past. Any current evidence is rejected simply because we cannot fix any problem found. Bigger, faster computers give the illusion of progress without solid fundamentals. This renders these expensive computers as meaningless.

“One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken. Once you give a charlatan power over you, you almost never get it back.” ― Carl Sagan

The Origins of V&V

I’ve noted many times that V&V is simply the practice of the scientific method. This implies that weak V&V means weak science. Lack of V&V is the lack of science. Science is an engine of innovation and progress. Lack of science is a lack of innovation and progress.

“The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.” ― George Orwell

V&V has been a major part of my career, and I’ve worked in the V&V program for ASC since its beginning. The way I got into it was through methods work in hydrodynamic methods and physics at Los Alamos. It is another passion in my career. That has ended up being catastrophic for me at the end. Both passions are not possible in the current environment. Thus, I’ve always seen a connection between V&V and the quest for improvement in the codes (methods and models). It is my firm belief that that connection is broken today. There is little or no impetus or willingness to improve codes aside from computing power. The result is a V&V program that’s degenerated into a rubber stamp. If the assessment is good, they’re accepted; if the assessment is negative they are rejected. Honesty has no place in the direction or dialogue.

V&V is an essential form of peer review for modeling and simulation. The problem is that the sort of peer review that V&V embodies has virtually faded from existence. The form of peer review that resulted in the creation of the V&V program is also gone. No longer does the program get subjected to that sort of real feedback. The peer review is manipulatedand cooked before it’s even done. Only a positive peer review is accepted. Any honest critique is just nibbling around the edges, mostly so the praise doesn’t look completely biased.

The origins of V&V are found in various industries that are heavily regulated by the government. These include nuclear storage and nuclear reactors. In both cases, modeling and simulation are essential to work. The basic V&V principles were defined there, and the first applications were found. In both cases, there were high-consequence circumstances that could only be studied via simulation. These are relatedto very big, dangerous, consequential decisions. All of them requiresome measure of faith in those simulations in order for them to be accepted. Sandia National Labs played a key role in defining the foundations of V&V. It was bound to the work of key people: Pat Roache, Bill Oberkampf, Chris Roy, Marty Pilch, Tim Trucano, …

This was a natural fit with stockpile stewardship and working on nuclear weapons once testing ended. Now, simulation is key to that endeavor, too. Being a natural fit didn’t mean it was putto work initially.

Inserting V&V into ASCI

“That which can be asserted without evidence, can be dismissed without evidence.” ― Christopher Hitchens

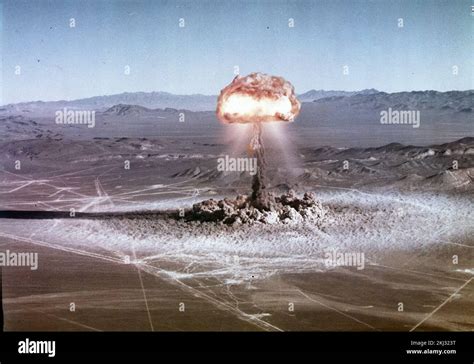

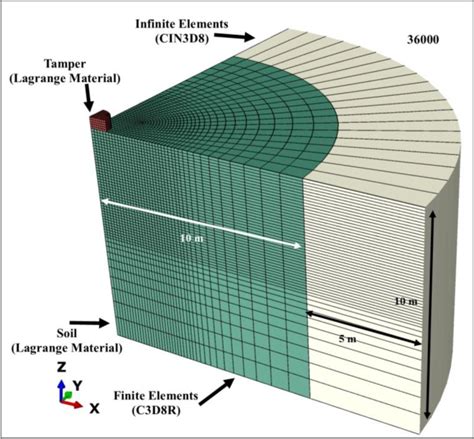

In 1992, the United States ceased to do full yield nuclear tests. Without the tests, the nation needed to ensure nuclear weapons worked properly using other techniques. This was called Stockpile Stewardship. The original program was simple in construction and concept. They would use the very best and fastest supercomputers to simulate weapons to replace that testing. We would build new experimental platforms. If you wanna know what it looked like, imagine what the Exascale Program recently looked like. Fast computers and codes with little other focus. Superficial comparisons with experiments would provide confidence.

In that time, there were a couple of main challenges.

1. The labs had lost their mainstay of funding and morale. The basic funding recipe also changed.

2. Basic identity was in free fall. The Labs were weak and despairing.

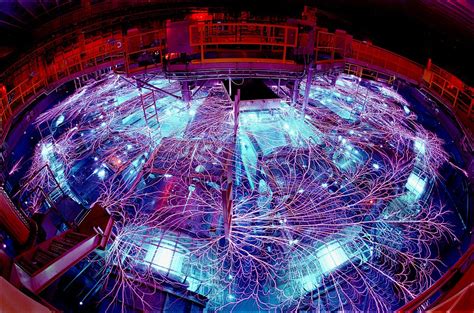

A complicating issue was that supercomputing was changing radically in the early 1990’s. We had entered the period where we needed to move from vector supercomputers defined by Cray to new classes of supercomputers defined by parallel computing. Thus, the basic structure and approach to writing the computer codes had to evolve. The labs had to rewrite codes extensively to use the new generation of computing. This offered an opportunity. The original program was devoid of seizing most of this opportunity. It was grossly superficial. Improving modeling and simulation with faster computers is simple. It is also a grossly insufficient half measure that ignores most of the power of computing. Physical models, better methods, and algorithms are all as powerful as faster computers. We see the same thing with current artificial intelligence approaches, and the conclusions are the same.

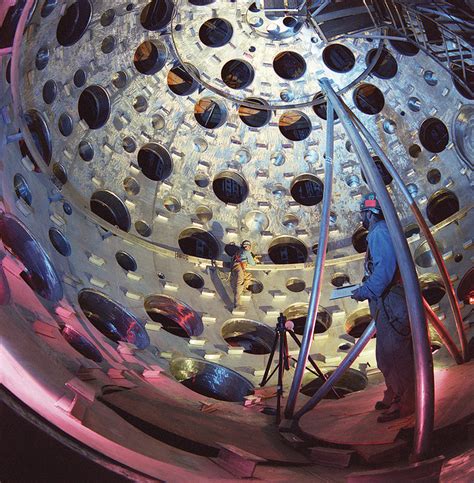

The problem with the program was that in order to fully replace testing, one needs far more basic science. This basic science is essential and augments what mere computing can provide. If you look at the value is of a computer, it depends on the mathematics and numerical methods used in the code. The models used in the codes are also essential and need to be developed. One also needs a program where one introduces other experimental data that is legally appropriate to obtain. These experiments provide as much of the basic character of a nuclear test as possible legally. This necessitates both a program where we understand the fidelity of those computer codes, and develop high-fidelity experimental facilities. This data is absolutely essential to the program’s validity. This program was the verification and validation program to synthesize these elements.

I should tell the story of how the ASC V&V program started. It all started with a high-stakes peer review around scientific concerns about ASCI (ASC). This resulted in a “Blue Ribbon Panel” formed to examine the program. The Blue Ribbon Panel Reviewis where I met Tim Trucano. Tim presented V&V to the panel, and I presented hydrodynamic methods research. It was a tense and difficult review in January 1999 in Washington DC. Travel was brutal as it followed on the heels of an East Coast blizzard. Out of this difficult review, the ASC program was reborn with the elements necessary for success listed above.

The V&V program was part of this. That crisis happened because of peer review. Experts from the national academies started to look at stockpile stewardship. It was a very important program for the nation, and they saw huge flaws in how the program was constructed. The program changed as a result and reaction. It made the program far better, too. For a while, the ASC program provided enormous boosts in the capability put into the codes. We had about 6-8 years of real scientific progress. The focus was on this broad-balance program that had supercomputing, but also modeling, numerical methods, and V&V. These all worked together to produce better modeling and simulation.

However, this era changed, and around 2007, this capability enhancement started to fade away. A big part of the death of peer review and the decay of the program was a management change. In 2006, LANL and LLNL both changed to corporate governance. The entire management model changed. The first to go was the methods development, which got folded into the code development. Then you saw a gradual diminishment of emphasis on modeling and V&V. Any and all critique of the codes and modeling became muted and light. The lack of peer review has hollowed out the quality of ASC and stockpile stewardship.

“Do you know what we call opinion in the absence of evidence? We call it prejudice.” ― Michael Crichton

The Death of Real Peer Review

Over the last 20 years, any sort of serious peer review has disappeared at the Labs. This puts national security at serious risk. It is essential to maintain high degrees of technical achievement and quality. The reasons are legion. Peer review is used to grade the labs and determine executive bonuses. Peer review causes plans to change and exposes problems. Peer review is difficult and painful. The combination of pain, grades, and money all works to undermine the willingness to accept critique. Today, this willingness has disappeared. We have allowed peer review to be managed in a way that makes it toothless and hollow.

What do we need?

Actual hard-nosed peer review with bona fide negative feedback. This is dead today. The management that now thinks that they basically walk into any review with either an A or an A+. As a result, we don’t have to bring our A game anymore. Instead, we justneed to work on our messaging and our ability to pull the wool over the eyes of the reviewers. The reviewers themselves know that the hard-nosed review isn’t welcome, so they pull all their punches too. It gets even worse the more you look at it. The reviews go into the executive bonus, so everyone knows executive compensation is at stake. No one wants to take money out of the boss’ pocket.

“The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command.” ― George Orwell

After the blue ribbon panel review and the welcome changes to ASC, they installed a continual review called the Burn Code Review. Just for those uninitiated, a burn code is a code that computes some of the most difficult parts of a nuclear weapons modeling, “The Burn”. This was extremely important and a huge challenge for the program. It was a hard-nosed and technicallyproficient expert review. This soon became too much for the program to take. So they replaced it with a review that was just advice. It became kinda like Tucker Carlson’s “Just Asking Questions” mantra instead of an actual review with grades. It’s very similar to the sort of grade inflation that’s taken place across universities.

You can look at the Ivy League, where everybody gets an A, no matter how good they are. I leave the Labs wondering if we have Schrodinger’s nuclear weapon. It either works or doesn’t work, but we don’t actually know. The difference is that the probabilities of it not working are constantly increasing. Without expertise in the right people working on it with honesty, we don’t know. Anything that could be a flashing warning sign is ignored. Concerns are simply brushed aside.

The end of the burn code review most clearly concedes to the lack of capability development in the program. When that ended, methods and models became fixed and unchanging. V&V simplybecame something that had the ability to rubber-stamp the results. Any negative feedback was unwelcome and could be rejected if it didn’t meet the political aims of the management. The political aims of the management became geared more and more as simply getting funding. They are not interested in what that funding actually did. It did not matter if what they were proposing was actually good or fit for the purpose of the stockpile.

The death of peer review at the labs is driven by the fact that the peer review goes into the grade that the labs get from the Department of Energy. So when a peer review is hard-nosed, the grade is low. When the grade is low, their bonus is actually affected. So everyone, the peer reviewers and the management, knows that a bad review leads to less money in the pocket of lab executives. Everyone knows that taking money out of your boss’s pocket is bad for your career. It also takes money out of everyone below the boss, too.

There’s an absolutely toxic knock-on effect to the lack of hard-nosed external peer review. Pretty soon, internal peer review becomes weak, too. It justrolls into a dirty snowball of mediocrity. With this comes a general sense that the lab is in decline rather than pushing forward. The pursuit of science and progress grinds to a halt. This is where we are today. I will note that the current program is starting to resemble the original program more fully. This is completely true if you look at how the AI program is constructed. The Cargo Cult is fully installed, and the Labs just offer really huge supercomputers.

“I think the educational and psychological studies I mentioned are examples of what I would like to call cargo cult science. In the South Seas there is a cargo cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things cargo cult science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.” ― Richard Feynman

A Cargo cult was an analogy introduced by Richard Feynman. This is science hollowed out from understanding and true meaning. This danger is very real. The methods, models, and codes are becoming less and less understood over time. The true nature of the simulation results is not critically examined. All of this is doubly true for artificial intelligence. The LLMs used by the Labs are black boxes. There is a very dim and limited understanding of how these models produce their results. We are not doing the science to produce understanding, nor the assessment. Rather than becoming a cargo cult, the AI effort is foundedas one.

This takes us to where we are today.

“No matter what he does, every person on earth plays a central role in the history of the world. And normally he doesn’t know it.” ― Paulo Coelho

The Decay to the Present

If you look at those elements of the program that were added, we can see that each of them has faded in intensity, focus, and importance. Today, method development in ASC is virtuallydead. The codes basically have fixed capability, and we’ve learned to accept our limitations. In fact, the limitations are permanent. Code verification can find simple bugs, but any deeper problem is not welcome. The resources to fix problems are not there. All the effort is going into putting codes on the new computers. This is true almost across the board. We have codes that are using antiquated, decrepit methods and are fading away from the state of the art.

The situation with modeling is marginally better, but really not all that healthy. The models in the codes are generally unsuitable and also antiquated. We move to where the program is largely just tweaking these models, providing calibration. We know many model are physically inappropriate for their use. They need continued exploration of improvements to remove unphysical calibration.

In a sense, the V&V program is the healthiest, but the rot that we see with methods and models is clearly happening there. The key is to look at the process. We’ve lost the ability to have vibrant peer review and accept and react to bad V&V results the way that a scientific organization should. In a healthy dynamic, we would take bad results and react. The right approach is to fix the codes; fix the models, and fix the methods depending on the evidence. Instead, bad results are rejected. There’s a feeling that there’s no money, expertise or willingness to engage in fixing anything. We’ve got into a place where V&V is merely a rubber stamp for mediocre work. Mark my words: The work is getting more and more mediocre with each passing year. Each passing year, there are fewer experts, and they are less heard.

If one wants to look at the future, one can see the Exascale program and the AI program. Both are basically modern carbon copies of the original ASCI program. It’s basically codes, supercomputers, and applications with little else.

What’s missing? The balance.

There needs to be a balance in science, and a balance in what goes on to the computers. We’ve lost the ability to understand that what goes on to the computer is as or more important than the computers themselves. My belief is that computing and supercomputing is an unbiased good. More computing is always better. What we should be asking ourselves is what we have sacrificed in order to get that supercomputing? Do we have the balance right? My sense is that today we don’t. V&V is the harbinger of that. The V&V program is simply a hollow version of what it once was and is no longer providing integrated, intimate, and fact-based feedback to the quality of what’s in the codes.

Take the Exascale program as a prime example. Instead of learning from the lessons of the ASCI program, the Exascale program was a step backwards. All computing and no science, just with the codes on faster computers and the science applications. The truth is that the computers do allow better science, but within the confines of the codes. The models and methods in the codes are equally important, both in terms of quality. Other foci are routes for improvement of results. Those improvements were completely sidelined by the focus on computing. A weak V&V program simply means progress or issues cannot be measured or detected. Both elements of V&V connect to objective reality. Reality is difficult and virtual reality isn’t. Current programs focus on the virtual because it can be easily managed.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” ― Mark Twain

The Future: AI as a Challenge

We see exactly the same mindset in how we’re pursuing AI today. It is all computing, along with various demo projects and hero calculations. No built-in credibility can be seen, nor any sort of sense that the credibility is important. The methods and algorithms built into AI are not a point of discussion. We have this magical belief that somehow scaling and raw computing will create the necessary conditions for artificial general intelligence (AGI). This is a virtual impossibility; the route to AGI is harder. The true result of both the Exascale program and our approach to AI is basicallyceding the future to China. We are making sure that the United States loses its supremacy in science. Each year we fall further behind.

The basic problem is that we’ve learned nothing from our experience. Instead of moving towards creating a more balanced and appropriate program that focuses on how science is actually accomplished, we’ve instead reverted to the original ASCI program. We have a pure focus on computing. The reasons for this are simple. It’s easy to sell to Congress. Big computers are good for business. The sales pitch is simple and Congress can see a computer. They cannot see math, code, or physics (they do like big experimental facilities). Instead of supporting science, the labs are simply subservient to the money.

One of the key metrics that one can look at is what it takes to double the quality of the solution within a computer code. If a computer code is converging at first-order accuracy, you have to double the mesh to double the accuracy. This is a reasonable rate for applied problems. For a 3D time-dependent problem, this means that a factor of 16 more computing will be neededto get twice the accuracy (assuming efficiency doesn’t degrade). This is an important thing to look at. If you have implicit algorithms that are not linearly efficient or poorly parallelized, that amount of computing will grow.

One of the starkly amazing things about artificial intelligence is that to double the capability of artificial intelligence computationally is vastly more expensive than it is for modeling and simulation codes. This also goes to the fact that AI is not based on physical laws that can be written down, but rather on data. One estimate I got from asking ChatGPT. So, take it with a big grain of salt! There, I applied the usual scaling laws for AI and found that to double the capability of an AI, you would need a million times more compute. Increase the parameter set, the number of values tweaked in the neural network, to be simple about it by 20,000 or a thousand times the amount of data.

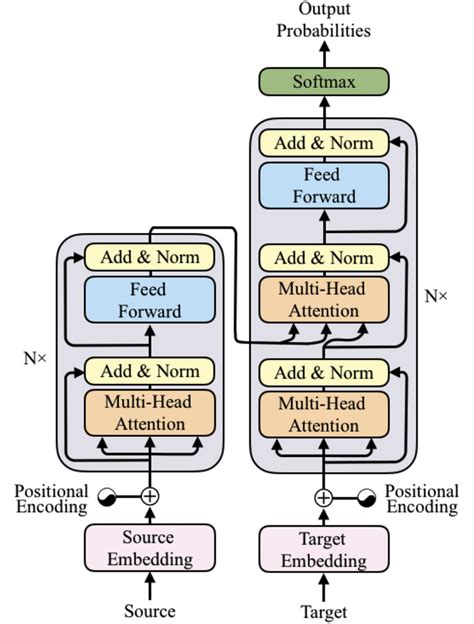

All of these numbers are vastly less efficient than those you have for modeling simulation. In addition, we do not have 1000 times the data to help. Take that, the breakthrough that caused the current AI boom was purelyan algorithmic invention. Granted, the algorithm was very well grafted onto the modern computing hardware. This was the Transformer algorithm. The big key was the attention mechanisms that produced a leap in capability. This was probably on the order of a factor of ten to a hundred.

The fact that algorithmic advances are not what we are focus is mind-boggling at best. It is plain stupidity. In modeling and simulation, the argument is that algorithms provide a bigger bang for the buck. They provide greater improvements than computers and has even more evidence in support of it. Yet, we do not actually do that there either. We are taking the same path with AI, with an even worse trajectory. This provides a deep condemnation of our ability to invest in progress. We ignore the evidence that is obvious and ubiquitous.

V&V builds trust. A program that avoids V&V, peer review, and evidence cannot be trusted. To trust simulations or AI, we need V&V. If we want simulations and AI to improve, we need V&V. All ofthis essential if these technologies achieve their potential. Today’s trends all point in the opposite direction. The technology is simply used without deep understanding or attention to correctness. This is the path to becoming a “Cargo Cult”.

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” ― Carl Sagan

All of this speaks volumes about the current environment. There we find ourselves in a place where peer review is light and unremittingly positive. Any negative review is rejected out of hand. We create systems that are structured so that the negative review never comes. The current management system cannot withstand a negative review and manages to never see one.

“The absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence.” ― Carl Sagan