What’s measured improves

― Peter F. Drucker

In area of endeavor standards of excellence are important. Numerical methods are no different. Every area of study has a standard set of test problems that researchers can demonstrate and study their work on. These test problems end up being used not just to communicate work, but also test whether work has been reproduced successfully or compare methods. Where the standards are sharp and refined the testing of methods has a degree of precision and results in actionable consequences. Where the standards are weak, expert judgment reigns and progress is stymied. In shock physics, the Sod shock tube (Sod 1978) is such a standard test. The problem is effectively a “hello World” problem for the field, but suffers from weak standards of acceptance focused on expert opinion of what is good and bad without any unbiased quantitative standard being applied. Ultimately, this weakness in accepted standards contributes to stagnant progress we are witnessing in the field. It also allows a rather misguided focus and assessment of capability to persist unperturbed by results (standards and metrics can energize progress, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/08/22/progress-is-incremental-then-it-isnt/).

In area of endeavor standards of excellence are important. Numerical methods are no different. Every area of study has a standard set of test problems that researchers can demonstrate and study their work on. These test problems end up being used not just to communicate work, but also test whether work has been reproduced successfully or compare methods. Where the standards are sharp and refined the testing of methods has a degree of precision and results in actionable consequences. Where the standards are weak, expert judgment reigns and progress is stymied. In shock physics, the Sod shock tube (Sod 1978) is such a standard test. The problem is effectively a “hello World” problem for the field, but suffers from weak standards of acceptance focused on expert opinion of what is good and bad without any unbiased quantitative standard being applied. Ultimately, this weakness in accepted standards contributes to stagnant progress we are witnessing in the field. It also allows a rather misguided focus and assessment of capability to persist unperturbed by results (standards and metrics can energize progress, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/08/22/progress-is-incremental-then-it-isnt/).

Sod’s shock tube is an example of a test problem being at the right time in the right place. It was published right at the nexus of progress in hyperbolic PDE’s, but before breakthroughs were well publicized. The article introduced a single problem applied to a large number of methods all of which performed poorly in one way or another. The methods were an amalgam of old and new methods demonstrating the general poor state of affairs for shock capturing methods in the late 1970’s. Since its publication is has become the opening ante for a method to demonstrate competence in computing shocks. The issues with this problem were highlighted in an earlier post, https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/08/18/getting-real-about-computing-shock-waves-myth-versus-reality/, where a variety of mythological thoughts are applied to computing shocks.

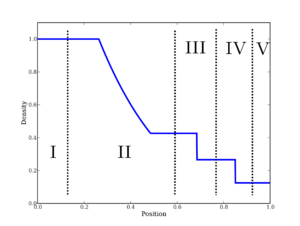

This problem is a very idealized shock problem in one dimension that is amenable to semi-analytical solution. As a result an effectively exact solution may be obtained via solution of nonlinear equations. The evaluation of the exact solution appropriately for comparison with numerical solutions is itself slightly nontrivial. The analytical solution needs to be properly integrated over the mesh cells to represent the correct integrated control volume values (more over this integration needs to be done for the correct conserved quantities). Comparison is usually done via the primitive variables, which may be derived from the conserved variable using standard techniques (I wrote about this a little while ago https://williamjrider.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/the-benefits-of-using-primitive-variables/ ). A shock tube is the flow that is results when two semi-infinite slabs of gas at different state conditions are held separately. They are then allowed to interact and a self-similar flow is created. This flow can contain all the basic compressible flow structures, shocks, rarefactions, and contact discontinuities.

Specifically, Sod’s shock tube (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sod_shock_tube) has the following conditions: in a one dimensional domain filled with an ideal gamma law gas,

Specifically, Sod’s shock tube (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sod_shock_tube) has the following conditions: in a one dimensional domain filled with an ideal gamma law gas, ,

, the domain is divided into two equal regions; on

,

; on

,

. The flow is described by the compressible Euler equations (conservation of mass,

, momentum

and energy

), and an equation of state,

. At time zero the flow develops a self-similar structure with a right moving shock followed by a contact discontinuity, and a left moving rarefaction (expansion fan). This is the classical Riemann problem. The solution may be found through semi-analytical means solving a nonlinear equation defined by the Rankine-Hugoniot relations (see Gottlieb and Groth for a wonderful exposition on this solution via Newton’s method).

The crux of the big issue with how this problem is utilized is that the analytical solution is not used for more than display in plotting comparisons with numerical solutions. The quality of numerical solutions is then only assessed qualitatively. This is a huge problem that directly inhibits progress. This is a direct result of having no standard beyond expert judgment on the quality. It leads to the classic “hand waving” argument for the quality of solutions. Actual quantitative differences are not discussed as part of the accepted standard. The expert can deftly focus on the parts of the solution they want to and ignore the parts that might be less beneficial to their argument. Real problems can persist and effectively be ignored (such as the very dissipative nature of some very popular high-order methods). Under this lack of standard relatively poorly performing methods can retain a high level of esteem while better performing methods are effectively ignored.

With all these problems, why does this state of affairs persist year after year? The first thing to note is that the standard of expert judgment is really good for experts. The expert can rule by asserting their expertise creating a bit of a flywheel effect. For experts whose favored methods would be exposed by better standards, it allows their continued use with relative impunity. The experts are then gate keepers for publications and standards, which tends to further the persistence of this sad state of affairs. The lack of any standard simply energizes the status quo and drives progress into hiding.

The key thing that has allowed this absurdity to exist for so long is the loss of accuracy associated with discontinuous solutions. For nonlinear solutions of the compressible Euler equations, high order accuracy is lost in shock capturing. As a result the designed order of accuracy for a computational method cannot be measured with a shock tube solution. As a result, one of the primary aims of verification is not achieved using this problem. One must always remember that order of accuracy is the confluence of two aspects, the method and the problem. Those stars need to align for the order of accuracy to be delivered.

Order of accuracy is almost always shown in results for other problems where no discontinuity exists. Typically a mesh refinement study, error norms, order of accuracy is provided as a matter of course. The same data is (almost) never shown for Sod’s shock tube. For discontinuous solutions the order of accuracy is (less than one). Ideally, the nonlinear features of the solution (shocks and expansions) converge at first-order, and the linearly degenerate feature (shears and contacts) converge at less than first order based on the details of the method (see the paper by Aslam, Banks and Rider (me). The core of the acceptance of the practice of not showing the error or convergence for shocked problems is the lack of differentiation of methods due to similar convergence rates for all methods (if they converge!). The relative security offered by the Lax-Wendroff theorem further emboldens people to ignore things (the weak solution guaranteed by it has to be entropy satisfying to be the right one!).

This is because the primal point of verification cannot be satisfied, but other aspects are still worth (or even essential) to pursue. Verification is also all about error estimation, and when the aims of order verification cannot be achieved, this becomes a primary concern. What people do not report and the aspect that is missing from the literature is the relatively large differences in error levels from different methods, and the impact of these differences practically. For most practical problems, the design order of accuracy cannot be achieved. These problems almost invariably converge at the lower order, but the level of error from a numerical method is still important, and may vary greatly based on details. In fact, the details and error levels actually have greater bearing on the utility of the method and its efficacy pragmatically under these conditions.

For all these reasons the current standard and practice with shock capturing methods are doing a great disservice to the community. The current practice inhibits progress by hiding deep issues and failing to expose the true performance of methods. Interestingly the source of this issue extends back to the inception of the problem by Sod. I want to be clear that Sod wasn’t to blame because none of the methods available to him were acceptable, but within 5 years very good methods arose, but the manner of presentation chosen originally persisted. Sod on showed qualitative pictures of the solution at a single mesh resolution (100 cells), and relative run times for the solution. This manner of presentation has persisted to the modern day (nearly 40 years almost without deviation). One can travel through the archival literature and see this pattern repeated over and over in an (almost) unthinking manner. The bottom line is that it is well past time to do better and set about using a higher standard.

For all these reasons the current standard and practice with shock capturing methods are doing a great disservice to the community. The current practice inhibits progress by hiding deep issues and failing to expose the true performance of methods. Interestingly the source of this issue extends back to the inception of the problem by Sod. I want to be clear that Sod wasn’t to blame because none of the methods available to him were acceptable, but within 5 years very good methods arose, but the manner of presentation chosen originally persisted. Sod on showed qualitative pictures of the solution at a single mesh resolution (100 cells), and relative run times for the solution. This manner of presentation has persisted to the modern day (nearly 40 years almost without deviation). One can travel through the archival literature and see this pattern repeated over and over in an (almost) unthinking manner. The bottom line is that it is well past time to do better and set about using a higher standard.

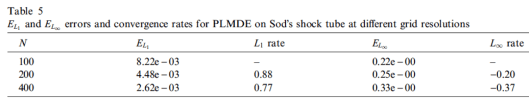

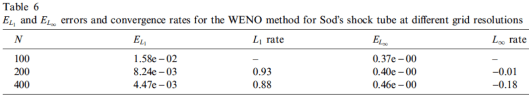

At a bare minimum we need to start reporting errors for these problems. This ought to not be enough, but it is an absolute minimum requirement. The problem is that the precise measurement of error is prone to vary due to details of implementation. This puts the onus on the full expression of the error measurement, itself an uncommon practice. It is uncommonly appreciated that the difference between different methods is actually substantial. For example in my own work with Jeff Greenough, the error level for the density in Sod’s problem between fifth order WENO, and a really good second-order MUSCL method is a factor of two in favor of the second-order method! (see Greenough and Rider 2004, the data is given in the tables below from the paper). This is exactly the sort of issue the experts are happy to resist exposing. Beyond this small step forward the application of mesh refinement with convergence testing should be standard practice. In reality we would be greatly served by looking at the rate of convergence to problems feature-by-feature. We could cut up the problem into regions and measure the error and rate of convergence separately for the shock, rarefaction and contact. This would provide a substantial amount of data that could be used to measure quality of solutions in detail and spur progress.

Two tables of data from Greenough and Rider 2004 displaying the density error for Sod’s problem (PLMDE = MUSCL).

We still use methods quite commonly that do not converge to the right solution for discontinuous problems (mostly in “production” codes). Without convergence testing this sort of pathology goes undetected. For a problem like Sod’s shock tube, it can still go undetected because the defect is relatively small. Usually it is only evident when the testing is on a more difficult problem with stronger shocks and rarefactions. Even then it is something that has to be looked for showing up as reduced convergence rates, or the presence of constant un-ordered error in the error structure, instead of the standard

. This subtlety is usually lost in a field where people don’t convergence test at all unless they expect full order of accuracy for the problem.

Now that I’ve thrown a recipe for improvement out there to consider, I think it’s worthwhile to defend expert judgment just a bit. Expertise has its role to play in progress. There are aspects of science that are not prone to measurement, science is still a human activity with tastes and emotion. This can be a force of good and bad, the need for dispassionate measurement is there as a counter-weight to the worst instincts of mankind. Expertise can be used to express a purely qualitative assessment that can make the difference between something that is merely good and great. Expert judgment can see through complexity to remediate results into a form with greater meaning. Expertise is more of a tiebreaker than the deciding factor. The problem today is that current practice means all we have is expert judgment and this is a complete recipe for the status quo and an utter lack of meaningful progress.

The important outcome from this discussion is crafting a path forward that makes the best use of our resources. Apply appropriate and meaningful metrics to the performance of methods and algorithms to make progress or lack of it concrete. Reduce, but retain the use of expertise and apply it to the qualitative aspects of results. The key to doing better is striking an appropriate balance. We don’t have it now, but getting to an improved practice is actually easy. This path is only obstructed by the tendency of the experts to hold onto their stranglehold.

An expert is someone who knows some of the worst mistakes that can be made in his subject, and how to avoid them.

― Werner Heisenberg

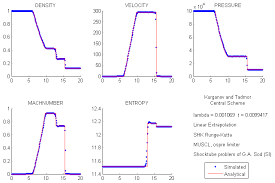

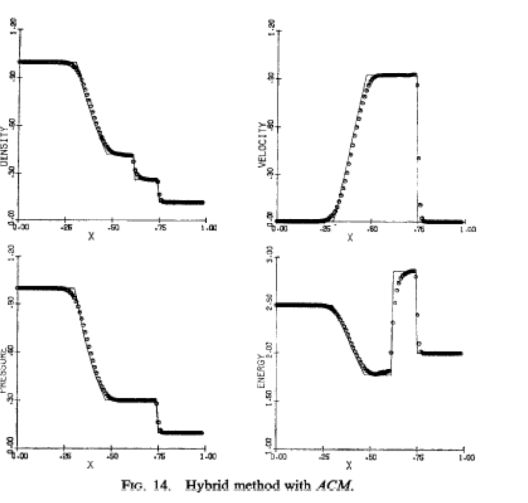

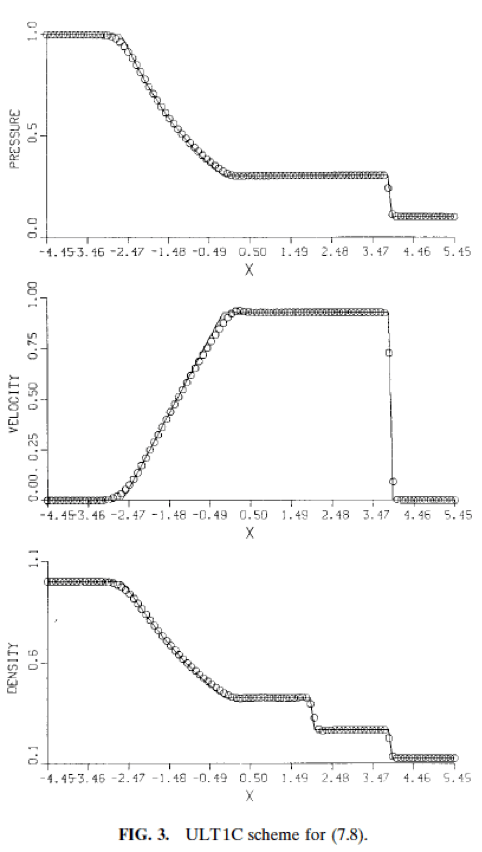

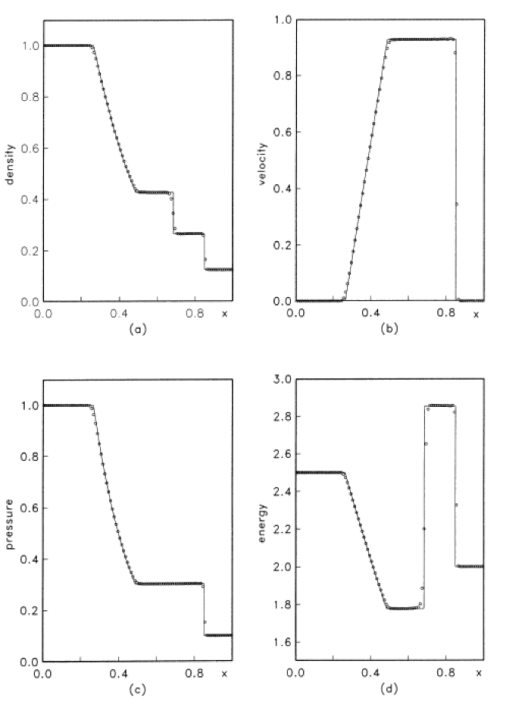

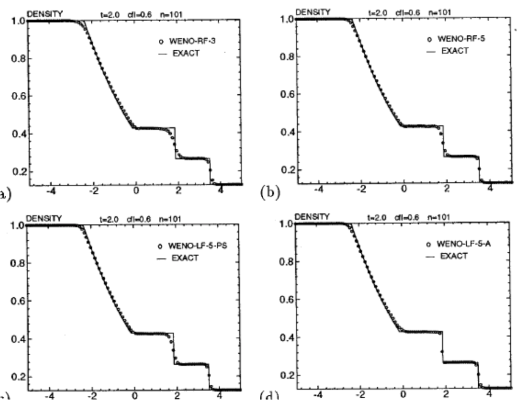

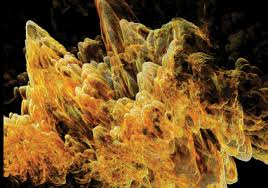

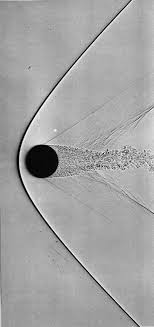

Historical montage of Sod shock tube results from Sod 1978, Harten 1983, Huynh 1996, Jiang and Shu 1996. First Sod’s result for perhaps the best performing method from his paper (just expert judgment on my part LOL).

Harten, Ami. “High resolution schemes for hyperbolic conservation laws.”Journal of computational physics 49, no. 3 (1983): 357-393.

Suresh, A., and H. T. Huynh. “Accurate monotonicity-preserving schemes with Runge–Kutta time stepping.” Journal of Computational Physics 136, no. 1 (1997): 83-99.

Jiang, Guang-Shan, and Chi-Wang Shu. “Efficient Implementation of Weighted ENO Schemes.” Journal of Computational Physics 126, no. 1 (1996): 202-228.

Sod, Gary A. “A survey of several finite difference methods for systems of nonlinear hyperbolic conservation laws.” Journal of computational physics 27, no. 1 (1978): 1-31.

Gottlieb, J. J., and C. P. T. Groth. “Assessment of Riemann solvers for unsteady one-dimensional inviscid flows of perfect gases.” Journal of Computational Physics 78, no. 2 (1988): 437-458.

Banks, Jeffrey W., T. Aslam, and W. J. Rider. “On sub-linear convergence for linearly degenerate waves in capturing schemes.” Journal of Computational Physics 227, no. 14 (2008): 6985-7002.

Greenough, J. A., and W. J. Rider. “A quantitative comparison of numerical methods for the compressible Euler equations: fifth-order WENO and piecewise-linear Godunov.” Journal of Computational Physics 196, no. 1 (2004): 259-281.

is exactly the spirit that has been utterly lost by the current high performance computer push. In a deep way the program lacks the appropriate humanity in its composition, which is absolutely necessary for progress.

is exactly the spirit that has been utterly lost by the current high performance computer push. In a deep way the program lacks the appropriate humanity in its composition, which is absolutely necessary for progress. enerated history of scientific computing. The key to the success and impact of scientific computing has been its ability to augment its foundational fields as a supplement to human’s innate intellect in an area that human’s ability is a bit diminished. While it supplements raw computational power, the impact of the field depends entirely on human’s natural talent as expressed in the base science and mathematics. One place of natural connection is the mathematical expression of the knowledge in basic science. Among the greatest sins of modern scientific computing is the diminished role of mathematics in the march toward progress.

enerated history of scientific computing. The key to the success and impact of scientific computing has been its ability to augment its foundational fields as a supplement to human’s innate intellect in an area that human’s ability is a bit diminished. While it supplements raw computational power, the impact of the field depends entirely on human’s natural talent as expressed in the base science and mathematics. One place of natural connection is the mathematical expression of the knowledge in basic science. Among the greatest sins of modern scientific computing is the diminished role of mathematics in the march toward progress. greater scientific computing. For example I work in an organization that is devoted to applied mathematics, yet virtually no mathematics actually takes place. Our applied mathematics programs have turned into software programs. Somehow the decision was made 20-30 years ago that software “weaponized” mathematics, and in the process the software became the entire enterprise, and the mathematics itself became lost, an afterthought of the process. Without the actual mathematical foundation for computing, important efficiencies, powerful insights and structural understanding is scarified.

greater scientific computing. For example I work in an organization that is devoted to applied mathematics, yet virtually no mathematics actually takes place. Our applied mathematics programs have turned into software programs. Somehow the decision was made 20-30 years ago that software “weaponized” mathematics, and in the process the software became the entire enterprise, and the mathematics itself became lost, an afterthought of the process. Without the actual mathematical foundation for computing, important efficiencies, powerful insights and structural understanding is scarified. raison d’être for math programs. In the process of the emphasis on the software instantiating mathematical ideas, the production and assault on mathematics has stalled. It has lost its centrality to the enterprise. This is horrible because there is so much yet to do.

raison d’être for math programs. In the process of the emphasis on the software instantiating mathematical ideas, the production and assault on mathematics has stalled. It has lost its centrality to the enterprise. This is horrible because there is so much yet to do. pletely unthinkable to be achieved. Discoveries make the impossible, possible, and we are denying ourselves the possibility of these results through our inept management of mathematics proper role in scientific computing. What might be some of the important topics in need of refined and focused mathematical thinking?

pletely unthinkable to be achieved. Discoveries make the impossible, possible, and we are denying ourselves the possibility of these results through our inept management of mathematics proper role in scientific computing. What might be some of the important topics in need of refined and focused mathematical thinking? y related to the multi-dimensional issues with compressible fluids is the topic of one of the Clay prizes. This is a million dollar prize for proving the existence of solutions to the Navier-Stokes equations. There is a deep problem with the way this problem is posed that may make its solution both impossible and practically useless. The equations posed in the problem statement are fundamentally wrong. They are physically wrong, not mathematically although this wrongness has consequences. In a very deep practical way fluids are never truly incompressible; incompressible is an approximation, but not a fact. This makes the equations have an intrinsically elliptic character (because incompressibility implies infinite sound speeds, and lack of thermodynamic character).

y related to the multi-dimensional issues with compressible fluids is the topic of one of the Clay prizes. This is a million dollar prize for proving the existence of solutions to the Navier-Stokes equations. There is a deep problem with the way this problem is posed that may make its solution both impossible and practically useless. The equations posed in the problem statement are fundamentally wrong. They are physically wrong, not mathematically although this wrongness has consequences. In a very deep practical way fluids are never truly incompressible; incompressible is an approximation, but not a fact. This makes the equations have an intrinsically elliptic character (because incompressibility implies infinite sound speeds, and lack of thermodynamic character). s such models tractable or not. The existence theory problems for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations are essential for turbulence. For a century it has largely been assumed that the Navier-Stokes equations describe turbulent flow with an acute focus on incompressibility. More modern understanding should have highlighted that the very mechanism we depend upon for creating the sort of singularities turbulence observations imply has been removed in the process of the choice of incompressibility. The irony is absolutely tragic. Turbulence brings almost an endless amount of difficulty to its study whether experimental, theoretical, or computational. In every case the depth of the necessary contributions by mathematics is vast. It seems somewhat likely that we have compounded the difficulty of turbulence by choosing a model with terrible properties. If so, it is likely that the problem remains unsolved, not due to its difficulty, but rather our blindness to the shortcomings, and the almost religious faith many have followed in attacking turbulence with such a model.

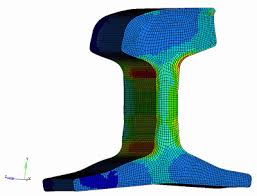

s such models tractable or not. The existence theory problems for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations are essential for turbulence. For a century it has largely been assumed that the Navier-Stokes equations describe turbulent flow with an acute focus on incompressibility. More modern understanding should have highlighted that the very mechanism we depend upon for creating the sort of singularities turbulence observations imply has been removed in the process of the choice of incompressibility. The irony is absolutely tragic. Turbulence brings almost an endless amount of difficulty to its study whether experimental, theoretical, or computational. In every case the depth of the necessary contributions by mathematics is vast. It seems somewhat likely that we have compounded the difficulty of turbulence by choosing a model with terrible properties. If so, it is likely that the problem remains unsolved, not due to its difficulty, but rather our blindness to the shortcomings, and the almost religious faith many have followed in attacking turbulence with such a model. es to problem solving. An area in need of fresh ideas, connections and better understanding is mechanics. This is a classical field with a rich and storied past, but suffering from a dire lack of connection between the classical mathematical rigor and the modern numerical world. Perhaps in no way is this more evident in the prevalent use of hypo-elastic models where hyper-elasticity would be far better. The hypo-elastic legacy comes from the simplicity of its numerical solution being the basis of methods and codes used around the World. It also only applies to very small incremental deformations. For the applications being studied, it should is invalid. In spite of this famous shortcoming, hypo-elasticity rules supreme, and hyper-elasticity sits in an almost purely academic role. Progress is needed here and mathematical rigor is part of the solution.

es to problem solving. An area in need of fresh ideas, connections and better understanding is mechanics. This is a classical field with a rich and storied past, but suffering from a dire lack of connection between the classical mathematical rigor and the modern numerical world. Perhaps in no way is this more evident in the prevalent use of hypo-elastic models where hyper-elasticity would be far better. The hypo-elastic legacy comes from the simplicity of its numerical solution being the basis of methods and codes used around the World. It also only applies to very small incremental deformations. For the applications being studied, it should is invalid. In spite of this famous shortcoming, hypo-elasticity rules supreme, and hyper-elasticity sits in an almost purely academic role. Progress is needed here and mathematical rigor is part of the solution. re less reliable). This area needs new ideas and a fresh perspective in the worst way. The second classical area of investigation that has stalled is high-order methods. I’ve written about this a lot. Needless to say we need a combination of new ideas, and a somewhat more honest and pragmatic assessment of what is needed in practical terms. We have to thread the needle of accuracy, efficiency and robustness in both cases. Again without mathematics holding us to the level of rigor it demands progress seems unlikely.

re less reliable). This area needs new ideas and a fresh perspective in the worst way. The second classical area of investigation that has stalled is high-order methods. I’ve written about this a lot. Needless to say we need a combination of new ideas, and a somewhat more honest and pragmatic assessment of what is needed in practical terms. We have to thread the needle of accuracy, efficiency and robustness in both cases. Again without mathematics holding us to the level of rigor it demands progress seems unlikely. orlds of physics and engineering need to seek mathematical rigor as a part of solidifying advances. Mathematics needs to seek inspiration from physics and engineering. Sometimes we need the pragmatic success in the ad hoc “seat of the pants” approach to provide the impetus for mathematical investigation. Finding out that something works tends to be a powerful driver to understanding why something works. For example the field of compressed sensing arose from a practical and pragmatic regularization method that worked without theoretical support. Far too much emphasis is placed on software and far too little on mathematical discovery and deep understand. We need a lot more discovery and understanding today, perhaps no place more than scientific computing!

orlds of physics and engineering need to seek mathematical rigor as a part of solidifying advances. Mathematics needs to seek inspiration from physics and engineering. Sometimes we need the pragmatic success in the ad hoc “seat of the pants” approach to provide the impetus for mathematical investigation. Finding out that something works tends to be a powerful driver to understanding why something works. For example the field of compressed sensing arose from a practical and pragmatic regularization method that worked without theoretical support. Far too much emphasis is placed on software and far too little on mathematical discovery and deep understand. We need a lot more discovery and understanding today, perhaps no place more than scientific computing! and terrifying shit show of the 2016 American Presidential election. It all seems to be coming together in a massive orgy of angst, lack of honesty and fundamental integrity across the full spectrum of life. As an active adult within this society I feel the forces tugging away at me, and I want to recoil from the carnage I see. A lot of days it seems safer to simply stay at home and hunker down and let this storm pass. It seems to be present at every level of life involving what is open and obvious to what is private and hidden.

and terrifying shit show of the 2016 American Presidential election. It all seems to be coming together in a massive orgy of angst, lack of honesty and fundamental integrity across the full spectrum of life. As an active adult within this society I feel the forces tugging away at me, and I want to recoil from the carnage I see. A lot of days it seems safer to simply stay at home and hunker down and let this storm pass. It seems to be present at every level of life involving what is open and obvious to what is private and hidden. the same thing is that progress depends on finding important, valuable problems and driving solutions. A second piece of integrity is hard work, persistence, and focus on the important valuable problems linked to great National or World concerns. Lastly, a powerful aspect of integrity is commitment to self. This includes a focus on self-improvement, and commitment to a full and well-rounded life. Every single bit of this is in rather precarious and constant tension, which is fine. What isn’t fine is the intrusion of outright bullshit into the mix undermining integrity at every turn.

the same thing is that progress depends on finding important, valuable problems and driving solutions. A second piece of integrity is hard work, persistence, and focus on the important valuable problems linked to great National or World concerns. Lastly, a powerful aspect of integrity is commitment to self. This includes a focus on self-improvement, and commitment to a full and well-rounded life. Every single bit of this is in rather precarious and constant tension, which is fine. What isn’t fine is the intrusion of outright bullshit into the mix undermining integrity at every turn. inimal value that get marketed as breakthroughs. The lack of integrity at the level of leadership simply takes this bullshit and passes it along. Eventually the bullshit gets to people who are incapable of recognizing the difference. Ultimately, the result of the acceptance of bullshit produces a lowering of standards, and undermines the reality of progress. Bullshit is the death of integrity in the professional world.

inimal value that get marketed as breakthroughs. The lack of integrity at the level of leadership simply takes this bullshit and passes it along. Eventually the bullshit gets to people who are incapable of recognizing the difference. Ultimately, the result of the acceptance of bullshit produces a lowering of standards, and undermines the reality of progress. Bullshit is the death of integrity in the professional world. within a vibrant and growing bullshit economy. Taken in this broad context, the dominance of bullshit in my professional life and the potential election of Donald Trump are closely connected.

within a vibrant and growing bullshit economy. Taken in this broad context, the dominance of bullshit in my professional life and the potential election of Donald Trump are closely connected. ated by fear mongering bullshit. Even worse it has paved the way for greater purveyors of bullshit like Trump. We may well see bullshit providing the vehicle to elect an unqualified con man as the President.

ated by fear mongering bullshit. Even worse it has paved the way for greater purveyors of bullshit like Trump. We may well see bullshit providing the vehicle to elect an unqualified con man as the President. e beauty of it is the made up shit can conform to whatever narrative you desire, and completely fit whatever your message is. In such a world real problems can simply be ignored when the path to progress is problematic for those in power.

e beauty of it is the made up shit can conform to whatever narrative you desire, and completely fit whatever your message is. In such a world real problems can simply be ignored when the path to progress is problematic for those in power. n the early days of computational science we were just happy to get things to work for simple physics in one spatial dimension. Over time, our grasp on more difficult coupled multi-dimensional physics became ever more bold and expansive. The quickest route to this goal was the use of operator splitting where the simple operators, single physics and one-dimensional were composed into complex operators. Most of our complex multiphysics codes operate in this operator split manner. Research into doing better almost always entails doing away with this composition of operators, or operator splitting and doing everything fully coupled. It is assumed that this is always superior. Reality is more difficult than this proposition, and most of the time the fully coupled or unsplit approach is actually worse with lower accuracy and greater expense with little identifiable benefits. So the question is should we keep trying to do this?

n the early days of computational science we were just happy to get things to work for simple physics in one spatial dimension. Over time, our grasp on more difficult coupled multi-dimensional physics became ever more bold and expansive. The quickest route to this goal was the use of operator splitting where the simple operators, single physics and one-dimensional were composed into complex operators. Most of our complex multiphysics codes operate in this operator split manner. Research into doing better almost always entails doing away with this composition of operators, or operator splitting and doing everything fully coupled. It is assumed that this is always superior. Reality is more difficult than this proposition, and most of the time the fully coupled or unsplit approach is actually worse with lower accuracy and greater expense with little identifiable benefits. So the question is should we keep trying to do this? solution involves a precise dynamic balance. This is when you have the situation of equal and opposite terms in the equations that produce solutions in near equilibrium. This produces critical points where solution make complete turns in outcomes based on the very detailed nature of the solution. These situations also produce substantial changes in the effective time scales of the solution. When very fast phenomena combine in this balanced form, the result is a slow time scale. It is most acute in the form of the steady-state solution where such balances are the full essence of the physical solution. This is where operator splitting is problematic and should be avoided.

solution involves a precise dynamic balance. This is when you have the situation of equal and opposite terms in the equations that produce solutions in near equilibrium. This produces critical points where solution make complete turns in outcomes based on the very detailed nature of the solution. These situations also produce substantial changes in the effective time scales of the solution. When very fast phenomena combine in this balanced form, the result is a slow time scale. It is most acute in the form of the steady-state solution where such balances are the full essence of the physical solution. This is where operator splitting is problematic and should be avoided. ods is their disadvantage for the fundamental approximations. When operators are discretized separately quite efficient and optimized approaches can be applied. For example if solving a hyperbolic equation it can be very effective and efficient to produce an extremely high-order approximation to the equations. For the fully coupled (unsplit) case such approximations are quite expensive, difficult and complex to produce. If the solution you are really interested in is first-order accurate, the benefit of the fully coupled case is mostly lost. This is with the distinct exception of small part of the solution domain where the dynamic balance is present and the benefits of coupling are undeniable.

ods is their disadvantage for the fundamental approximations. When operators are discretized separately quite efficient and optimized approaches can be applied. For example if solving a hyperbolic equation it can be very effective and efficient to produce an extremely high-order approximation to the equations. For the fully coupled (unsplit) case such approximations are quite expensive, difficult and complex to produce. If the solution you are really interested in is first-order accurate, the benefit of the fully coupled case is mostly lost. This is with the distinct exception of small part of the solution domain where the dynamic balance is present and the benefits of coupling are undeniable. method should be adaptive and locally tailored to the nature of the solution. One size fits all is almost never the right answer (to anything). Unfortunately this whole line of attack is not favored by anyone these days, we seem to be stuck in the worst of both worlds where codes used for solving real problems are operator split, and research is focused on coupling without regard for the demands of reality. We need to break out of this stagnation! This is ironic because stagnation is one of the things that coupled methods excel at!

method should be adaptive and locally tailored to the nature of the solution. One size fits all is almost never the right answer (to anything). Unfortunately this whole line of attack is not favored by anyone these days, we seem to be stuck in the worst of both worlds where codes used for solving real problems are operator split, and research is focused on coupling without regard for the demands of reality. We need to break out of this stagnation! This is ironic because stagnation is one of the things that coupled methods excel at! Today’s title is a conclusion that comes from my recent assessments and experiences at work. It has completely thrown me off stride as I struggle to come to terms with the evidence in front of me. The obvious and reasonable conclusions from the consideration of recent experiential evidence directly conflicts with most of my most deeply held values. As a result I find myself in a deep quandary about how to proceed with work. Somehow my performance is perceived to be better when I don’t care much about my work. One reasonable conclusion is that when I have little concern about outcomes of the work, I don’t show my displeasure when those outcomes are poor.

Today’s title is a conclusion that comes from my recent assessments and experiences at work. It has completely thrown me off stride as I struggle to come to terms with the evidence in front of me. The obvious and reasonable conclusions from the consideration of recent experiential evidence directly conflicts with most of my most deeply held values. As a result I find myself in a deep quandary about how to proceed with work. Somehow my performance is perceived to be better when I don’t care much about my work. One reasonable conclusion is that when I have little concern about outcomes of the work, I don’t show my displeasure when those outcomes are poor. nal integrity is important to pay attention to. Hard work, personal excellence and a devotion to progress has been the path to my success professionally. The only thing that the current environment seems to favor is hard work (and even that’s questionable). The issues causing tension are related to technical and scientific quality, or work that denotes any commitment to technical excellence. It’s everything I’ve written about recently, success with high performance computing, progress in computational science, and integrity in peer review. Attention to any and all of these topics is a source of tension that seems to be completely unwelcome. We seem to be managed to mostly pay attention to nothing but the very narrow and well-defined boundaries of work. Any thinking or work “outside the box” seems to invite ire, punishment and unhappiness. Basically, the evidence seems to indicate that my performance is perceived to be much better if I “stay in the box”. In other words I am managed to be predictable and well defined in my actions, don’t provide any surprises.

nal integrity is important to pay attention to. Hard work, personal excellence and a devotion to progress has been the path to my success professionally. The only thing that the current environment seems to favor is hard work (and even that’s questionable). The issues causing tension are related to technical and scientific quality, or work that denotes any commitment to technical excellence. It’s everything I’ve written about recently, success with high performance computing, progress in computational science, and integrity in peer review. Attention to any and all of these topics is a source of tension that seems to be completely unwelcome. We seem to be managed to mostly pay attention to nothing but the very narrow and well-defined boundaries of work. Any thinking or work “outside the box” seems to invite ire, punishment and unhappiness. Basically, the evidence seems to indicate that my performance is perceived to be much better if I “stay in the box”. In other words I am managed to be predictable and well defined in my actions, don’t provide any surprises. The only way I can “stay in the box” is to turn my back on the same values that brought me success. Most of my professional success is based on doing “out of the box” thinking working to provide real progress on important issues. Recently it’s been pretty clear that this isn’t appreciated any more. To stop thinking out of the box I need to stop giving a shit. Every time I seem to care more deeply about work and do something extra not only is it not appreciated; it gets me into trouble. Just do the minimum seems to be the real directive, and extra effort is not welcome seem to be the modern mantra. Do exactly what you’re told to do, no more and no less. This is the path to success.

The only way I can “stay in the box” is to turn my back on the same values that brought me success. Most of my professional success is based on doing “out of the box” thinking working to provide real progress on important issues. Recently it’s been pretty clear that this isn’t appreciated any more. To stop thinking out of the box I need to stop giving a shit. Every time I seem to care more deeply about work and do something extra not only is it not appreciated; it gets me into trouble. Just do the minimum seems to be the real directive, and extra effort is not welcome seem to be the modern mantra. Do exactly what you’re told to do, no more and no less. This is the path to success. done the experiment and the evidence was absolutely clear. When I don’t care, don’t give a shit and have different priorities than work, I get awesome performance reviews. When I do give a shit, it creates problems. A big part of the problem is the whole “in the box” and “out of the box” issue. We are managed to provide predictable results and avoid surprises. It is all part of the low risk mindset that permeates the current World, and the workplace as well. Honesty and progress is a source of tension (i.e., risk) and as such it makes waves, and if you make waves you create problems. Management doesn’t like tension, waves or anything that isn’t completely predictable. Don’t cause trouble or make problems, just do stuff that makes us look good. The best way to provide this sort of outcome is just come to work and do what you’re expected to do, no more, no less. Don’t be creative and let someone else tell you what is important. In other words, don’t give a shit, or better yet don’t give fuck either.

done the experiment and the evidence was absolutely clear. When I don’t care, don’t give a shit and have different priorities than work, I get awesome performance reviews. When I do give a shit, it creates problems. A big part of the problem is the whole “in the box” and “out of the box” issue. We are managed to provide predictable results and avoid surprises. It is all part of the low risk mindset that permeates the current World, and the workplace as well. Honesty and progress is a source of tension (i.e., risk) and as such it makes waves, and if you make waves you create problems. Management doesn’t like tension, waves or anything that isn’t completely predictable. Don’t cause trouble or make problems, just do stuff that makes us look good. The best way to provide this sort of outcome is just come to work and do what you’re expected to do, no more, no less. Don’t be creative and let someone else tell you what is important. In other words, don’t give a shit, or better yet don’t give fuck either.

The news is full of stories and outrage at Hillary Clinton’s e-mail scandal. I don’t feel that anyone has remotely the right perspective on how this happened, and why it makes perfect sense in the current system. It epitomizes a system that is prone to complete breakdown because of the deep neglect of information systems both unclassified and classified within the federal system. We just don’t pay IT professionals enough to get good service. The issue also gets to the heart of the overall treatment of classified information by the United States that is completely out of control. The tendency to classify things is completely running amok far beyond anything that is in the actual best interests of society. To

The news is full of stories and outrage at Hillary Clinton’s e-mail scandal. I don’t feel that anyone has remotely the right perspective on how this happened, and why it makes perfect sense in the current system. It epitomizes a system that is prone to complete breakdown because of the deep neglect of information systems both unclassified and classified within the federal system. We just don’t pay IT professionals enough to get good service. The issue also gets to the heart of the overall treatment of classified information by the United States that is completely out of control. The tendency to classify things is completely running amok far beyond anything that is in the actual best interests of society. To compound things, further it highlights the utter and complete disparity in how laws and rules do not apply to the rich and powerful. All of this explains what happened, and why; yet it doesn’t make what she did right or justified. Instead it points out why this sort of thing is both inevitable and much more widespread (i.e., John Deutch, Condoleezza Rich, Colin Powell,

compound things, further it highlights the utter and complete disparity in how laws and rules do not apply to the rich and powerful. All of this explains what happened, and why; yet it doesn’t make what she did right or justified. Instead it points out why this sort of thing is both inevitable and much more widespread (i.e., John Deutch, Condoleezza Rich, Colin Powell, and what is surely a much longer list of violations of the same thing Clinton did).

and what is surely a much longer list of violations of the same thing Clinton did). Last week I had to take some new training at work. It was utter torture. The DoE managed to find the worst person possible to train me, and managed to further drain them of all personality then treated him with sedatives. I already take a massive amount of training, most of which utterly and completely useless. The training is largely compliance based, and generically a waste of time. Still by the already appalling standards, the new training was horrible. It is the Hillary-induced E-mail classification training where I now have the authority to mark my classified E-mails as an “E-mail derivative classifier”. We are constantly taking reactive action via training that only undermines the viability and productivity of my workplace. Like most my training, this current training is completely useless, and only serves the “cover your ass” purpose that most training serves. Taken as a whole our environment is corrosive and undermines any and all motivation to give a single fuck about work.

Last week I had to take some new training at work. It was utter torture. The DoE managed to find the worst person possible to train me, and managed to further drain them of all personality then treated him with sedatives. I already take a massive amount of training, most of which utterly and completely useless. The training is largely compliance based, and generically a waste of time. Still by the already appalling standards, the new training was horrible. It is the Hillary-induced E-mail classification training where I now have the authority to mark my classified E-mails as an “E-mail derivative classifier”. We are constantly taking reactive action via training that only undermines the viability and productivity of my workplace. Like most my training, this current training is completely useless, and only serves the “cover your ass” purpose that most training serves. Taken as a whole our environment is corrosive and undermines any and all motivation to give a single fuck about work. professionals work on old hardware with software restrictions that serve outlandish and obscene security regulations that in many cases are actually counter-productive. So, if Hillary were interested in getting anything done she would be quite compelled to leave the federal network for greener, more productive pastures.

professionals work on old hardware with software restrictions that serve outlandish and obscene security regulations that in many cases are actually counter-productive. So, if Hillary were interested in getting anything done she would be quite compelled to leave the federal network for greener, more productive pastures. ything is not my or anyone’s actual productivity, but rather the protection of information, or at least the appearance of protection. Our approach to everything is administrative compliance with directives. Actual performance on anything is completely secondary to the appearance of performance. The result of this pathetic approach to providing the taxpayer with benefit for money expended is a dysfunctional system that provides little in return. It is primed for mistakes and outright systematic failures. Nothing stresses the system more than a high-ranking person hell-bent on doing their job. The sort of people who ascend to high positions like Hillary Clinton find the sort of compliance demanded by the system awful (because it is), and have the power to ignore it.

ything is not my or anyone’s actual productivity, but rather the protection of information, or at least the appearance of protection. Our approach to everything is administrative compliance with directives. Actual performance on anything is completely secondary to the appearance of performance. The result of this pathetic approach to providing the taxpayer with benefit for money expended is a dysfunctional system that provides little in return. It is primed for mistakes and outright systematic failures. Nothing stresses the system more than a high-ranking person hell-bent on doing their job. The sort of people who ascend to high positions like Hillary Clinton find the sort of compliance demanded by the system awful (because it is), and have the power to ignore it. Of course I’ve seen this abuse of power live and in the flesh. Take the former Los Alamos Lab Director, Admiral Pete Nanos who famously shut the Lab down an denounced the staff as “Butthead Cowboys!” He blurted out classified information in an unclassified meeting in front of hundreds if not thousands of people. If he had taken his training, and been compliant he should have known better. Instead of being issued a security infraction like any of the butthead cowboys in attendance would have gotten, he got a pass. The powers that be simply declassified the material and let him slide by. Why? Power comes with privileges. When you’re in a position of power you find the rules are different. This is a maxim repeated over and over in our World. Some of this looks like white privilege, or rich white privilege where you can get away with smoking pot, or raping unconscious girls with no penalty, or lightened penalties. If you’re not white or not rich you pay a much stiffer penalty including prison time.

Of course I’ve seen this abuse of power live and in the flesh. Take the former Los Alamos Lab Director, Admiral Pete Nanos who famously shut the Lab down an denounced the staff as “Butthead Cowboys!” He blurted out classified information in an unclassified meeting in front of hundreds if not thousands of people. If he had taken his training, and been compliant he should have known better. Instead of being issued a security infraction like any of the butthead cowboys in attendance would have gotten, he got a pass. The powers that be simply declassified the material and let him slide by. Why? Power comes with privileges. When you’re in a position of power you find the rules are different. This is a maxim repeated over and over in our World. Some of this looks like white privilege, or rich white privilege where you can get away with smoking pot, or raping unconscious girls with no penalty, or lightened penalties. If you’re not white or not rich you pay a much stiffer penalty including prison time.

complete and utter bullshit. People who have highlighted huge systematic abuses of power involving murder and vast violation of constitutional law are thrown to the proverbial wolves. There is no protection, it is viewed as treason and these people are treated as harshly as possible (Snowden, Assange, and Manning come to mind). As I’ve noted above people in positions of authority can violate the law with utter impunity. At the same time classification is completely out of control. More and mo

complete and utter bullshit. People who have highlighted huge systematic abuses of power involving murder and vast violation of constitutional law are thrown to the proverbial wolves. There is no protection, it is viewed as treason and these people are treated as harshly as possible (Snowden, Assange, and Manning come to mind). As I’ve noted above people in positions of authority can violate the law with utter impunity. At the same time classification is completely out of control. More and mo re is being classified with less and less control. Such classification often only serves to hide information and serve the needs of the status quo power structure.

re is being classified with less and less control. Such classification often only serves to hide information and serve the needs of the status quo power structure. I’ll just say up front that my contention is that there is precious little excellence to be found today in many fields. Modeling & simulation is no different. I will also contend that excellence is relatively easy to obtain, or at the very least a key change in mindset will move us in that direction. This change in mindset is relatively small, but essential. It deals with the general setting of satisfaction with the current state and whether restlessness exists that ends up allowing progress to be sought. Too often there seems to be an innate satisfaction with too much of the “ecosystem” for modeling & simulation, and not enough agitation for progress. We should continually seek the opportunity and need for progress in the full spectrum of work. Our obsession with planning, and micromanagement of research ends up choking the success from everything it touches by short-circuiting the entire natural process of progress, discovery and serendipity.

I’ll just say up front that my contention is that there is precious little excellence to be found today in many fields. Modeling & simulation is no different. I will also contend that excellence is relatively easy to obtain, or at the very least a key change in mindset will move us in that direction. This change in mindset is relatively small, but essential. It deals with the general setting of satisfaction with the current state and whether restlessness exists that ends up allowing progress to be sought. Too often there seems to be an innate satisfaction with too much of the “ecosystem” for modeling & simulation, and not enough agitation for progress. We should continually seek the opportunity and need for progress in the full spectrum of work. Our obsession with planning, and micromanagement of research ends up choking the success from everything it touches by short-circuiting the entire natural process of progress, discovery and serendipity. n my view the desire for continual progress is the essence of excellence. When I see the broad field of modeling & simulation the need for progress seems pervasive and deep. When I hear our leaders talk such needs are muted and progress seems to only depend on a few simple areas of focus. Such a focus is always warranted if there is an opportunity to be taken advantage of. Instead we seem to be in an age where the technological opportunity being sought is arrayed against progress, computer hardware. In the process of trying to force progress where it is less available the true engines of progress are being shut down. This represents mismanagement of epic proportions and needs to be met with calls for sanity and intelligence in our future.

n my view the desire for continual progress is the essence of excellence. When I see the broad field of modeling & simulation the need for progress seems pervasive and deep. When I hear our leaders talk such needs are muted and progress seems to only depend on a few simple areas of focus. Such a focus is always warranted if there is an opportunity to be taken advantage of. Instead we seem to be in an age where the technological opportunity being sought is arrayed against progress, computer hardware. In the process of trying to force progress where it is less available the true engines of progress are being shut down. This represents mismanagement of epic proportions and needs to be met with calls for sanity and intelligence in our future. The way toward excellence, innovation and improvement is to figure out how to break what you have. Always push your code to its breaking point; always know what reasonable (or even unreasonable) problems you can’t successfully solve. Lack of success can be defined in multiple ways including complete failure of a code, lack of convergence, lack of quality, or lack of accuracy. Generally people test their code where it works and if they are good code developers they continue to test the code all the time to make sure it still works. If you want to get better you push at the places where the code doesn’t work, or doesn’t work well. You make the problems where it didn’t work part of the ones that do work. This is the simple and straightforward way to progress, and it is stunning how few efforts follow this simple, and obvious path. It is the golden path that we deny ourselves of today.

The way toward excellence, innovation and improvement is to figure out how to break what you have. Always push your code to its breaking point; always know what reasonable (or even unreasonable) problems you can’t successfully solve. Lack of success can be defined in multiple ways including complete failure of a code, lack of convergence, lack of quality, or lack of accuracy. Generally people test their code where it works and if they are good code developers they continue to test the code all the time to make sure it still works. If you want to get better you push at the places where the code doesn’t work, or doesn’t work well. You make the problems where it didn’t work part of the ones that do work. This is the simple and straightforward way to progress, and it is stunning how few efforts follow this simple, and obvious path. It is the golden path that we deny ourselves of today. n the success of modeling & simulation to date. We are too satisfied that the state of the art is fine and good enough. We lack a general sense that improvements, and progress are always possible. Instead of a continual striving to improve, the approach of focused and planned breakthroughs has beset the field. We have a distinct management approach that provides distinctly oriented improvements while ignoring important swaths of the technical basis for modeling & simulation excellence. The result of this ignorance is an increasingly stagnant status quo that embraces “good enough” implicitly through a lack of support for “better”.

n the success of modeling & simulation to date. We are too satisfied that the state of the art is fine and good enough. We lack a general sense that improvements, and progress are always possible. Instead of a continual striving to improve, the approach of focused and planned breakthroughs has beset the field. We have a distinct management approach that provides distinctly oriented improvements while ignoring important swaths of the technical basis for modeling & simulation excellence. The result of this ignorance is an increasingly stagnant status quo that embraces “good enough” implicitly through a lack of support for “better”. Modeling & simulation arose to utility in support of real things. It owes much of its prominence to the support of national defense during the cold war. Everything from fighter planes to nuclear weapons to bullets and bombs utilized modeling & simulation to strive toward the best possible weapon. Similarly modeling & simulation moved into the world of manufacturing aiding in the design and analysis of cars, planes and consumer products across the spectrum of the economy. The problem is that we have lost sight of the necessity of these real world products as the engine of improvement in modeling & simulation. Instead we have allowed computer hardware to become an end unto itself rather than simply a tool. Even in computing, hardware has little centrality to the field. In computing today, the “app” is king and the keys to the market hardware is simply a necessary detail.

Modeling & simulation arose to utility in support of real things. It owes much of its prominence to the support of national defense during the cold war. Everything from fighter planes to nuclear weapons to bullets and bombs utilized modeling & simulation to strive toward the best possible weapon. Similarly modeling & simulation moved into the world of manufacturing aiding in the design and analysis of cars, planes and consumer products across the spectrum of the economy. The problem is that we have lost sight of the necessity of these real world products as the engine of improvement in modeling & simulation. Instead we have allowed computer hardware to become an end unto itself rather than simply a tool. Even in computing, hardware has little centrality to the field. In computing today, the “app” is king and the keys to the market hardware is simply a necessary detail. To address the proverbial “elephant in the room” the national exascale program is neither a good goal, nor bold in any way. It is the actual antithesis of what we need for excellence. The entire program will only power the continued decline in achievement in the field. It is a big project that is being managed the same way bridges are built. Nothing of any excellence will come of it. It is not inspirational or aspirational either. It is stale. It is following the same path that we have been on for the past 20 years, improvement in modeling & simulation by hardware. We have tremendous places we might harness modeling & simulation to help produce and even enable great outcomes. None of these greater societal goods is in the frame with exascale. It is a program lacking a soul.

To address the proverbial “elephant in the room” the national exascale program is neither a good goal, nor bold in any way. It is the actual antithesis of what we need for excellence. The entire program will only power the continued decline in achievement in the field. It is a big project that is being managed the same way bridges are built. Nothing of any excellence will come of it. It is not inspirational or aspirational either. It is stale. It is following the same path that we have been on for the past 20 years, improvement in modeling & simulation by hardware. We have tremendous places we might harness modeling & simulation to help produce and even enable great outcomes. None of these greater societal goods is in the frame with exascale. It is a program lacking a soul. The title is a bit misleading so it could be concise. A more precise one would be “Progress is mostly incremental; then progress can be (often serendipitously) massive” Without accepting incremental progress as the usual, typical outcome, the massive leap forward is impossible. If incremental progress is not sought as the natural outcome of working with excellence, progress dies completely. The gist of my argument is that attitude and orientation is the key to making things better. Innovation and improvement are the result of having the right attitude and orientation rather than having a plan for it. You cannot schedule breakthroughs, but you can create an environment and work with an attitude that makes it possible, if not likely. The maddening thing about breakthroughs is their seemingly random nature, you cannot plan for them they just happen, and most of the time they don’t.

The title is a bit misleading so it could be concise. A more precise one would be “Progress is mostly incremental; then progress can be (often serendipitously) massive” Without accepting incremental progress as the usual, typical outcome, the massive leap forward is impossible. If incremental progress is not sought as the natural outcome of working with excellence, progress dies completely. The gist of my argument is that attitude and orientation is the key to making things better. Innovation and improvement are the result of having the right attitude and orientation rather than having a plan for it. You cannot schedule breakthroughs, but you can create an environment and work with an attitude that makes it possible, if not likely. The maddening thing about breakthroughs is their seemingly random nature, you cannot plan for them they just happen, and most of the time they don’t. modern management seems to think that innovation is something to be managed for and everything can be planned. Like most things where you just try too damn hard, this management approach has exactly the opposite effect. We are actually unintentionally, but actively destroying the environment that allows progress, innovation and breakthroughs to happen. The fastidious planning does the same thing. It is a different thing than having a broad goal and charter that pushes toward a better tomorrow. Today we are expected to plan our research like we are building a goddamn bridge! It is not even remotely the same! The result is the opposite and we are getting less for every research dollar than ever before.

modern management seems to think that innovation is something to be managed for and everything can be planned. Like most things where you just try too damn hard, this management approach has exactly the opposite effect. We are actually unintentionally, but actively destroying the environment that allows progress, innovation and breakthroughs to happen. The fastidious planning does the same thing. It is a different thing than having a broad goal and charter that pushes toward a better tomorrow. Today we are expected to plan our research like we are building a goddamn bridge! It is not even remotely the same! The result is the opposite and we are getting less for every research dollar than ever before. A large part of the problem with our environment is an obsession with measuring performance by the achievement of goals or milestones. Instead of working to create a super productive and empowering work place where people work exceptionally by intrinsic motivation, we simply set “lofty” goals and measure their achievement. The issue is the mindset implicit in the goal setting and measuring; this is the lack of trust in those doing the work. Instead of creating an environment and work processes that enable the best performance, we define everything in terms of milestones. These milestones and the attitudes that surround them sew the seeds of destruction, not because goals are wrong or bad, but because the behavior driven by achieving management goals is so corrosively destructive.

A large part of the problem with our environment is an obsession with measuring performance by the achievement of goals or milestones. Instead of working to create a super productive and empowering work place where people work exceptionally by intrinsic motivation, we simply set “lofty” goals and measure their achievement. The issue is the mindset implicit in the goal setting and measuring; this is the lack of trust in those doing the work. Instead of creating an environment and work processes that enable the best performance, we define everything in terms of milestones. These milestones and the attitudes that surround them sew the seeds of destruction, not because goals are wrong or bad, but because the behavior driven by achieving management goals is so corrosively destructive.

So the difference is really simple and clear. You must be expanding the state of the art, or defining what it means to be world class. Simply being at the state of the art or world class is not enough. Progress depends on being committed and working actively at improving upon and defining state of the art and world-class work. Little improvements can lead to the massive breakthroughs everyone aspires toward, and really are the only way to get them. Generally all these things are serendipitous and depend entirely on a culture that creates positive change and prizes excellence. One never really knows where the tipping point is and getting to the breakthrough depends mostly on the faith that it is out there waiting to be discovered.

So the difference is really simple and clear. You must be expanding the state of the art, or defining what it means to be world class. Simply being at the state of the art or world class is not enough. Progress depends on being committed and working actively at improving upon and defining state of the art and world-class work. Little improvements can lead to the massive breakthroughs everyone aspires toward, and really are the only way to get them. Generally all these things are serendipitous and depend entirely on a culture that creates positive change and prizes excellence. One never really knows where the tipping point is and getting to the breakthrough depends mostly on the faith that it is out there waiting to be discovered. Computing the solution to flows containing shock waves used to be exceedingly difficult, and for a lot of reasons it is now modestly difficult. Solutions for many problems may now be considered routine, but numerous pathologies exist and the limit of what is possible still means research progress are vital. Unfortunately there seems to be little interest in making such progress from those funding research, it goes in the pile of solved problems. Worse yet, there a numerous preconceptions about results, and standard practices about how results are presented that contend to inhibit progress. Here, I will outline places where progress is needed and how people discuss research results in a way that furthers the inhibitions.

Computing the solution to flows containing shock waves used to be exceedingly difficult, and for a lot of reasons it is now modestly difficult. Solutions for many problems may now be considered routine, but numerous pathologies exist and the limit of what is possible still means research progress are vital. Unfortunately there seems to be little interest in making such progress from those funding research, it goes in the pile of solved problems. Worse yet, there a numerous preconceptions about results, and standard practices about how results are presented that contend to inhibit progress. Here, I will outline places where progress is needed and how people discuss research results in a way that furthers the inhibitions. table. To do the best job means making some hard choices that often fly in the face of ideal circumstances. By making these hard choices you can produce far better methods for practical use. It often means sacrificing things that might be nice in an ideal linear world for the brutal reality of a nonlinear world. I would rather have something powerful and functional in reality than something of purely theoretical interest. The published literature seems to be opposed to this point-of-view with a focus on many issues of little practical importance.

table. To do the best job means making some hard choices that often fly in the face of ideal circumstances. By making these hard choices you can produce far better methods for practical use. It often means sacrificing things that might be nice in an ideal linear world for the brutal reality of a nonlinear world. I would rather have something powerful and functional in reality than something of purely theoretical interest. The published literature seems to be opposed to this point-of-view with a focus on many issues of little practical importance. upon this example. Worse yet, the difficulty of extending Lax’s work is monumental. Moving into high dimensions invariably leads to instability and flow that begins to become turbulent, and turbulence is poorly understood. Unfortunately we are a long way from recreating Lax’s legacy in other fields (see e.g.,

upon this example. Worse yet, the difficulty of extending Lax’s work is monumental. Moving into high dimensions invariably leads to instability and flow that begins to become turbulent, and turbulence is poorly understood. Unfortunately we are a long way from recreating Lax’s legacy in other fields (see e.g.,  where it does not. Progress in turbulence is stagnant and clearly lacks key conceptual advances necessary to chart a more productive path. It is vital to do far more than simply turn codes loose on turbulent problems and let great solutions come out because they won’t. Nonetheless, it is the path we are on. When you add shocks and compressibility to the mix, everything gets so much worse. Even the most benign turbulence is poorly understood much less anything complicated. It is high time to inject some new ideas into the study rather than continue to hammer away at the failed old ones. In closing this vignette, I’ll offer up a different idea: perhaps the essence of turbulence is compressible and associated with shocks rather than being largely divorced from these physics. Instead of building on the basis of the decisively unphysical aspects of incompressibility, turbulence might be better built upon a physical foundation of compressible (thermodynamic) flows with dissipative discontinuities (shocks) that fundamental observations call for and current theories cannot explain.

where it does not. Progress in turbulence is stagnant and clearly lacks key conceptual advances necessary to chart a more productive path. It is vital to do far more than simply turn codes loose on turbulent problems and let great solutions come out because they won’t. Nonetheless, it is the path we are on. When you add shocks and compressibility to the mix, everything gets so much worse. Even the most benign turbulence is poorly understood much less anything complicated. It is high time to inject some new ideas into the study rather than continue to hammer away at the failed old ones. In closing this vignette, I’ll offer up a different idea: perhaps the essence of turbulence is compressible and associated with shocks rather than being largely divorced from these physics. Instead of building on the basis of the decisively unphysical aspects of incompressibility, turbulence might be better built upon a physical foundation of compressible (thermodynamic) flows with dissipative discontinuities (shocks) that fundamental observations call for and current theories cannot explain. Let’s get to one of the biggest issues that confounds the computation of shocked flows, accuracy, convergence and order-of-accuracy. For computing shock waves, the order of accuracy is limited to first-order for everything emanating from any discontinuity (Majda & Osher 1977). Further more nonlinear systems of equations will invariably and inevitably create discontinuities spontaneously (Lax 1973). In spite of these realities the accuracy of solutions with shocks still matters, yet no one ever measures it. The reasons why it matter are far more subtle and refined, and the impact of accuracy is less pervasive in its victory. When a flow is smooth enough to allow high-order convergence, the accuracy of the solution with high-order methods is unambiguously superior. With smooth solutions the highest order method is the most efficient if you are solving for equivalent accuracy. When convergence is limited to first-order the high-order methods effectively lower the constant in front of the error term, which is less efficient. One then has the situation where the gains with high-order must be balanced with the cost of achieving high-order. In very many cases this balance is not achieved.