Maturity, one discovers, has everything to do with the acceptance of ‘not knowing.

― Mark Z. Danielewski

U ncertainty quantification is a hot topic. It is growing in importance and practice, but people should be realistic about it. It is always incomplete. We hope that we have captured the major forms of uncertainty, but the truth is that our assumptions about simulation blind us to some degree. This is the impact of “unknown knowns” the assumptions we make without knowing we are making them. In most cases our uncertainty estimates are held hostage to the tools at our disposal. One way of thinking about this looks at codes as the tools, but the issue is far deeper actually being the basic foundation we base of modeling of reality upon.

ncertainty quantification is a hot topic. It is growing in importance and practice, but people should be realistic about it. It is always incomplete. We hope that we have captured the major forms of uncertainty, but the truth is that our assumptions about simulation blind us to some degree. This is the impact of “unknown knowns” the assumptions we make without knowing we are making them. In most cases our uncertainty estimates are held hostage to the tools at our disposal. One way of thinking about this looks at codes as the tools, but the issue is far deeper actually being the basic foundation we base of modeling of reality upon.

… Nature almost surely operates by combining chance with necessity, randomness with determinism…

― Eric Chaisson

One of the really uplifting trends in computational simulations is the focus on uncertainty estimation as part of the solution. This work is serving the demands of decision makers who increasingly depend on simulation. The practice allows simulations to come with a multi-faceted “error” bar. Just like the simulations themselves the uncertainty is going to be imperfect, and typically far more imperfect than the simulations themselves. It is important to recognize the nature of imperfection and incompleteness inherent in uncertainty quantification. The uncertainty itself comes from a number of sources, some interchangeable.

One of the really uplifting trends in computational simulations is the focus on uncertainty estimation as part of the solution. This work is serving the demands of decision makers who increasingly depend on simulation. The practice allows simulations to come with a multi-faceted “error” bar. Just like the simulations themselves the uncertainty is going to be imperfect, and typically far more imperfect than the simulations themselves. It is important to recognize the nature of imperfection and incompleteness inherent in uncertainty quantification. The uncertainty itself comes from a number of sources, some interchangeable.

Sometimes the hardest pieces of a puzzle to assemble, are the ones missing from the box.

― Dixie Waters

Let’s explore the basic types of uncertainty we study:

Epistemic: This is the uncertainty that comes from lack of knowledge. This could be associated with our imperfect modeling of systems and phenomena, or materials. It could come from our lack of knowledge regarding the precise composition and configuration of the systems we study. It could come from the lack of modeling for physical processes or features of a system (e.g., neglecting radiation transport, or relativistic effects). Epistemic uncertainty is the dominant form of uncertainty reported because tools exist to estimate it, and it treats simulation codes like “black boxes”.

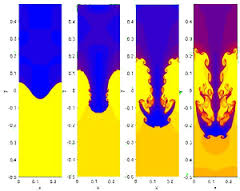

Aleatory: This is uncertainty due to the variability of phenomena. This is the weather. The archetype of variability is turbulence, but also think about the detailed composition of every single device. They are all different in some small degree never mind their history after being built. To some extent aleatory uncertainty is associated with a breakdown of continuum hypothesis and is distinctly scale dependent. As things are simulated at smaller scales different assumptions must be made. Systems will vary at a range of length and time scales, and as scales come into focus their variation must be simulated. One might argue that this is epistemic, in that if we could measure things precisely enough then it could be precisely simulated (given the right equations, constitutive equation and boundary conditions). This point of view is rational and constructive only to a small degree. For many systems of interest chaos reigns and measurements will never be precise enough to matter. By and large this form of uncertainty is simply ignored because simulations can’t provide information.

Aleatory: This is uncertainty due to the variability of phenomena. This is the weather. The archetype of variability is turbulence, but also think about the detailed composition of every single device. They are all different in some small degree never mind their history after being built. To some extent aleatory uncertainty is associated with a breakdown of continuum hypothesis and is distinctly scale dependent. As things are simulated at smaller scales different assumptions must be made. Systems will vary at a range of length and time scales, and as scales come into focus their variation must be simulated. One might argue that this is epistemic, in that if we could measure things precisely enough then it could be precisely simulated (given the right equations, constitutive equation and boundary conditions). This point of view is rational and constructive only to a small degree. For many systems of interest chaos reigns and measurements will never be precise enough to matter. By and large this form of uncertainty is simply ignored because simulations can’t provide information.

Numerical: Simulations involve taking a “continuous” system and cutting them up into discrete pieces. Insofar as the equations describe reality the solutions should approach a correct solution as these pieces get more numerous (and smaller). This is the essence of mesh refinement. Computational simulation is predicated upon this notion to an increasingly ridiculous degree. Regardless of the viability of the notion, the approximations made numerically are a source of error to be included in any error bar. Too often these errors are ignored, wrongly assumed to be small, or incorrectly estimated. There is no excuse for this today.

bar. Too often these errors are ignored, wrongly assumed to be small, or incorrectly estimated. There is no excuse for this today.

Users: the last sources of uncertainty examined are the people who use codes and construct models to be solved. As problem complexity grows the decisions in modeling become more subtle and prone to variability. Quite often modelers of equal skill will come up with distinctly different answers or uncertainties. Usually a problem is only modeled once, so this form of uncertainty (or the requisite uncertainty on the uncertainty) is completely hidden from view. Unless there is an understanding of how the problem definition and solution choices impact the solution, the uncertainty will be unquantified. Knowledge of this uncertainty is almost always larger for complex problems where it is less likely for the simulations to be conducted by independent teams. Studies have shown this to be as large or larger than other sources! Almost the only place this has received any systematic attention is nuclear reactor safety analysis.

As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality.

― Albert Einstein

One has to acknowledge that the line between epistemic and aleatory is necessarily fuzzy. In a sense the balance is tipped toward epistemic because of the tools exist to study it. At some level this is a completely unsatisfactory state of affairs. Some features of systems arise from the random behavior of the constituent parts of the system. Systems and their circumstances are just a little different, and these differences yield differences (sometimes slight) in the response. Sometimes these small differences create huge changes in the outcomes. It is these huge changes that drive a great deal of worry in decision-making. Addressing these issue is a huge challenge for computational modeling and simulation; a challenge that we simply aren’t addressing at all today.

Why?

The assumption of an absolute determinism is the essential foundation of every scientific enquiry.

― Max Planck

A large part of the reason for failing to address these matters is the implicit, but slavish devotion to determinism. Simulations are almost always viewed as the solution to a deterministic problem. This means there is AN answer. Answers are almost never sought in the sense of a probability distribution. Even probabilistic methods like Monte Carlo are trying to approach the deterministic solution. Reality is almost never AN answer and almost always a distribution. What we end up solving is the mean expected response of a system to the average circumstance. What is actually observed is a distribution of responses to a distribution of circumstances. Often the real question to answer in any study (with or without simulation) is what’s the worse that can reasonably happen? A level of confidence that says 95% or 99% of the responses will be less than some bad level usually defines the desired result. This sort of question is best thought of as aleatory, and our current simulation capability doesn’t begin to address it.

A large part of the reason for failing to address these matters is the implicit, but slavish devotion to determinism. Simulations are almost always viewed as the solution to a deterministic problem. This means there is AN answer. Answers are almost never sought in the sense of a probability distribution. Even probabilistic methods like Monte Carlo are trying to approach the deterministic solution. Reality is almost never AN answer and almost always a distribution. What we end up solving is the mean expected response of a system to the average circumstance. What is actually observed is a distribution of responses to a distribution of circumstances. Often the real question to answer in any study (with or without simulation) is what’s the worse that can reasonably happen? A level of confidence that says 95% or 99% of the responses will be less than some bad level usually defines the desired result. This sort of question is best thought of as aleatory, and our current simulation capability doesn’t begin to address it.

When your ideas shatter established thought, expect blowback.

― Tim Fargo

The key aspect of this entire problem is a slavish devotion to determinism in modeling. Almost every modeling discipline sees the solution being sought as being utterly deterministic. This is lo gical if the conditions being modeled are known with exceeding precision. The problem is that such precision is virtually impossible for any circumstance. This is the core of the problem with simulating the aleatory uncertainty that so frequently remains untreated. It is almost completely ignored by a host of fundamental assumption in modeling that is inherited by simulations. These assumptions are holding back real progress in a host of fields of major importance.

gical if the conditions being modeled are known with exceeding precision. The problem is that such precision is virtually impossible for any circumstance. This is the core of the problem with simulating the aleatory uncertainty that so frequently remains untreated. It is almost completely ignored by a host of fundamental assumption in modeling that is inherited by simulations. These assumptions are holding back real progress in a host of fields of major importance.

Finally we must combine all these uncertainties to get our putative “error bar”. There are a number of ways to go about this combination with varying properties. The most popular knee-jerk approach is to use the root mean square of the contributions (square root of the sum of the squares). The sum of the absolute values would be a better and safer choice, since it is always larger (hence more conservative) than the sum of squares. If you’re feeling cavalier and want to play it dangerous, just use the largest uncertainty. Each of these choices is related to probabilistic assumptions, which in the case of sum of squares is assuming a normal distribution.

It is impossible to trap modern physics into predicting anything with perfect determinism because it deals with probabilities from the outset.

― Arthur Stanley Eddington

One of the most pernicious and deepening issues associated with uncertainty quantification is “black box” thinking. In many cases the simulation code is viewed as being a black box where the user knows very about its workings beyond a purely functional level. This often results in generic and generally uninformed decisions being made on uncertainty. The expectations of the models and numerical methods are understood only superficially, and this results in a superficial uncertainty estimate. Often the black box thinking extends to the tool used to get uncertainty too. We then get the result from a superposition of two black boxes. Not a lot light bets shed on reality in the process. Numerical errors are ignored, or simply misdiagnosed. Black box users often simply do a mesh sensitivity study, and assume that small changes under mesh variation are indicative of convergence and small errors. They may or may not be such evidence. Without doing a more formal analysis this sort of conclusion is not justified. If code and problem is not converging, the small changes may be indicative of very large numerical errors or even divergence and a complete lack of control.

methods are understood only superficially, and this results in a superficial uncertainty estimate. Often the black box thinking extends to the tool used to get uncertainty too. We then get the result from a superposition of two black boxes. Not a lot light bets shed on reality in the process. Numerical errors are ignored, or simply misdiagnosed. Black box users often simply do a mesh sensitivity study, and assume that small changes under mesh variation are indicative of convergence and small errors. They may or may not be such evidence. Without doing a more formal analysis this sort of conclusion is not justified. If code and problem is not converging, the small changes may be indicative of very large numerical errors or even divergence and a complete lack of control.

Whether or not it is clear to you,

no doubt the universe is unfolding

as it should.

― Max Ehrmann

The answer to this problem is deceptively simple make things “white box” testing. The problem is that making our black boxes into white boxes is far from simple. Perhaps the hardest thing about this is having people doing the modeling and simulation with sufficient expertise to treat the tools as white boxes. A more reasonable step forward is for people to simply realize the dangers inherent in black box testing mentality.

Science is a way of thinking much more than it is a body of knowledge.

― Carl Sagan

In many respects uncertainty quantification is in its infancy. The techniques are immature and terribly incomplete. Beyond this character, we are deeply tied to modeling philosophies that hold us back from progress. The whole field needs to mature and throw off the shackles imposed by the legacy of Newton and the entire rule of determinism that still holds much of science under its spell.

The riskiest thing we can do is just maintain the status quo.

― Bob Iger

Moore’s law isn’t a law, but rather an empirical observation that has held sway for far longer than could have been imagined fifty years ago. In some way shape or form, Moore’s law has provided a powerful narrative for the triumph of computer technology in our modern World. For a while it seemed almost magical in its gift of massive growth in computing power over the scant passage of time. Like all good things, it will come to an end, and soon if not already.

Moore’s law isn’t a law, but rather an empirical observation that has held sway for far longer than could have been imagined fifty years ago. In some way shape or form, Moore’s law has provided a powerful narrative for the triumph of computer technology in our modern World. For a while it seemed almost magical in its gift of massive growth in computing power over the scant passage of time. Like all good things, it will come to an end, and soon if not already.

For those of us doing real practical work on computers this program is a disaster. Even doing the same things we do today will be harder and more expensive. It is likely that the practical work will get harder to complete and more difficult to be sure of. Real gains in throughput are likely to be far less than the reported gains in performance attributed to the new computers too. In sum the program will almost certainly be a massive waste of money. The plan is for most of the money going to the hardware and the hardware vendors (should I think corporate welfare?). All of this will be done to squeeze another 7 to 10 years of life out of Moore’s law even though the patient is metaphorically in a coma already.

For those of us doing real practical work on computers this program is a disaster. Even doing the same things we do today will be harder and more expensive. It is likely that the practical work will get harder to complete and more difficult to be sure of. Real gains in throughput are likely to be far less than the reported gains in performance attributed to the new computers too. In sum the program will almost certainly be a massive waste of money. The plan is for most of the money going to the hardware and the hardware vendors (should I think corporate welfare?). All of this will be done to squeeze another 7 to 10 years of life out of Moore’s law even though the patient is metaphorically in a coma already. If someone gives you some data and asks you to fit a function that “models” the data, many of you know the intuitive answer, “least squares”. This is the obvious, simple choice, and perhaps, not surprisingly, not the best answer. How bad this choice may be depends on the situation? One way to do better is to recognize the situations where the solution via least squares may be problematic, and produce an undue influence on the results.

If someone gives you some data and asks you to fit a function that “models” the data, many of you know the intuitive answer, “least squares”. This is the obvious, simple choice, and perhaps, not surprisingly, not the best answer. How bad this choice may be depends on the situation? One way to do better is to recognize the situations where the solution via least squares may be problematic, and produce an undue influence on the results. one. If the deviations are large or some of your data might be corrupt (i.e., outliers), the choice of least squares can be catastrophic. The corrupt data may have a completely overwhelming impact on the fit. There are a number of methods for dealing with outliers in least squares, and in my opinion none of them good.

one. If the deviations are large or some of your data might be corrupt (i.e., outliers), the choice of least squares can be catastrophic. The corrupt data may have a completely overwhelming impact on the fit. There are a number of methods for dealing with outliers in least squares, and in my opinion none of them good. Fortunately there are existing methods that are free from these pathologies. For example the least median deviation fit can deal with corrupt data easily. It naturally excludes outliers from the fit because of a different underlying model. Where least squares are the solution of a minimization problem in the energy or L2 norm, the least median deviation uses the L1 norm. The problem is that the fitting algorithm is inherently nonlinear, and generally not included in most software.

Fortunately there are existing methods that are free from these pathologies. For example the least median deviation fit can deal with corrupt data easily. It naturally excludes outliers from the fit because of a different underlying model. Where least squares are the solution of a minimization problem in the energy or L2 norm, the least median deviation uses the L1 norm. The problem is that the fitting algorithm is inherently nonlinear, and generally not included in most software.

One of the problems is that least squares are virtually knee-jerk in its application. It is contained in standard software such as Microsoft Excel and can be applied with almost no thought. If you have to write your own curve-fitting program by far the simplest approach is to use least squares. It can often produce a linear system of equations to solve where alternatives are invariably nonlinear. The key point is to realize that this convenience has a consequence. If your data reduction is important, it might be a good idea to think about what you ought to do a bit more.

One of the problems is that least squares are virtually knee-jerk in its application. It is contained in standard software such as Microsoft Excel and can be applied with almost no thought. If you have to write your own curve-fitting program by far the simplest approach is to use least squares. It can often produce a linear system of equations to solve where alternatives are invariably nonlinear. The key point is to realize that this convenience has a consequence. If your data reduction is important, it might be a good idea to think about what you ought to do a bit more.

A week ago I received bad news, the review for a paper were back. One might think that getting a review back would be good, but it rarely is. These reviews are too often a horrible soul-crushing experience. In this case I had reports from two reviewers, and one of them delivered the ego thrashing I’ve come to fear.

A week ago I received bad news, the review for a paper were back. One might think that getting a review back would be good, but it rarely is. These reviews are too often a horrible soul-crushing experience. In this case I had reports from two reviewers, and one of them delivered the ego thrashing I’ve come to fear. In total the two reviews were generally consistent on the details of the paper, and the sorts of suggestions for bringing the paper into the condition needed to allow publication. The difference was the tone of the reviews. One of the reviews was completely constructive and detailed in its critique. Each and every critique was offered in a positive light even when the error was pure carelessness.

In total the two reviews were generally consistent on the details of the paper, and the sorts of suggestions for bringing the paper into the condition needed to allow publication. The difference was the tone of the reviews. One of the reviews was completely constructive and detailed in its critique. Each and every critique was offered in a positive light even when the error was pure carelessness. it could have been much easier. There is nothing wrong with being critical, but the way its done matters a lot.

it could have been much easier. There is nothing wrong with being critical, but the way its done matters a lot.

Scientific computing is still dominated by the same two big uses that existed at the beginning. Recently data analysis has reasserted itself as the big “new” thing. This is mostly the consequence of the deluge of data coming from the Internet, and the impending Internet of things. For mainstream science, the initial value problem still holds sway for a broader set of activities although data is big in astronomy, geophysics and social sciences.

Scientific computing is still dominated by the same two big uses that existed at the beginning. Recently data analysis has reasserted itself as the big “new” thing. This is mostly the consequence of the deluge of data coming from the Internet, and the impending Internet of things. For mainstream science, the initial value problem still holds sway for a broader set of activities although data is big in astronomy, geophysics and social sciences.

I don’t think software gets the support or respect it deserves particularly in scientific computing. It is simply too important to treat it the way we do. It should be regarded as an essential professional contribution and supported as such. Software shouldn’t be a one-time investment either; it requires upkeep and constant rebuilding to be healthy. Too often we pay for the first version of the code then do everything else on the cheap. The code decays and ultimately is overcome by technical debt. The final danger with code is the loss of the knowledge basis for the code itself. Too much scientific software is “magic” code that no one understands. If no one understands the code, the code is probably dangerous to use.

I don’t think software gets the support or respect it deserves particularly in scientific computing. It is simply too important to treat it the way we do. It should be regarded as an essential professional contribution and supported as such. Software shouldn’t be a one-time investment either; it requires upkeep and constant rebuilding to be healthy. Too often we pay for the first version of the code then do everything else on the cheap. The code decays and ultimately is overcome by technical debt. The final danger with code is the loss of the knowledge basis for the code itself. Too much scientific software is “magic” code that no one understands. If no one understands the code, the code is probably dangerous to use. computing. The connection to work of importance and value is essential to understand, and the lack of such understanding explains why our current trajectory is so problematic. Just to reiterate, the value of computing, or scientific computing is found in the real world. The real world is studied through the use of models in scientific computing that are most often differential equations. Using algorithms or methods we then solve these models. These models as interpreted by their solution methods or algorithms are expressed in computer code, which in turn runs on a computer.

computing. The connection to work of importance and value is essential to understand, and the lack of such understanding explains why our current trajectory is so problematic. Just to reiterate, the value of computing, or scientific computing is found in the real world. The real world is studied through the use of models in scientific computing that are most often differential equations. Using algorithms or methods we then solve these models. These models as interpreted by their solution methods or algorithms are expressed in computer code, which in turn runs on a computer.

More importantly software often outlives the people responsible for the intellectual capital represented in it. A real danger is the loss of expertise in what the software is actually doing. There is a specific and real danger in using software that isn’t understood. Many times the software is used as a library and not explicitly understood by the user. The software is treated as a storehouse of ideas, but if those ideas are not fully understood there is danger. It is important that the ideas in software be alive and fully comprehended.

More importantly software often outlives the people responsible for the intellectual capital represented in it. A real danger is the loss of expertise in what the software is actually doing. There is a specific and real danger in using software that isn’t understood. Many times the software is used as a library and not explicitly understood by the user. The software is treated as a storehouse of ideas, but if those ideas are not fully understood there is danger. It is important that the ideas in software be alive and fully comprehended.