In working on an algorithm (or a code) we are well advised to think carefully about requirements and priorities. It is my experience that these can be stated clearly as a set of adjectives about the method or code that form the title of this post. Moreover the order of these adjectives forms the order of the priorities from the users of the code. The priorities of those funding code development are quite often the direct opposite!

There is nothing quite so useless as doing with great efficiency something that should not be done at all.

– Peter Drucker

None of these priorities can be ignored. For example if the efficiency becomes too poor, the code won’t be used because time is money. A code that is too inaccurate won’t be used no matter how robust it is (these go together, with accurate and robust being a sort of “holy grail”).

None of these priorities can be ignored. For example if the efficiency becomes too poor, the code won’t be used because time is money. A code that is too inaccurate won’t be used no matter how robust it is (these go together, with accurate and robust being a sort of “holy grail”).

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

― Carl Sagan

The problem I’d like to raise your attention to be that the people handing out money to do the work seem inverts these priorities. This creates a distinct problem with making the work useful and impactful. The over-riding concern is the high-performance computing imperative, which is encoded in the call for efficiency. There is an operating assumption that all of the other characteristics are well in hand, and its just a matter of getting a computer (big and) fast enough to crush our problems out of sight and out of mind. Ironically, the meeting devoted to this dim-sighted worldview is this week, SC14. Thankfully, I’m not there.

All opinions are not equal. Some are a very great deal more robust, sophisticated and well supported in logic and argument than others.

― Douglas Adams

Robust. A robust code runs to completion. Robustness in its most refined and crudest sense is stability. The refined sense of robustness is the numerical stability that is so keenly important, but it is so much more. It gives an answer come hell or high water even if that answer is complete crap. Nothing upsets your users more than no answer; a bad answer is better than none at all. Making a code robust is hard work and difficult especially if you have morals and standards. It is an imperative.

Robust. A robust code runs to completion. Robustness in its most refined and crudest sense is stability. The refined sense of robustness is the numerical stability that is so keenly important, but it is so much more. It gives an answer come hell or high water even if that answer is complete crap. Nothing upsets your users more than no answer; a bad answer is better than none at all. Making a code robust is hard work and difficult especially if you have morals and standards. It is an imperative.

Physical. Getting physical answers is often thought of as being equal to robustness, and it should be. It isn’t so this needs to be a separate category. In a sense physical answers are a better source of robustness, that is, an upgrade. An example is that the density of a material must remain positive-definite, or velocities remain sub-luminal, and things like that. A deeper take on physicality involves quantities staying inside bounds imposed, or satisfaction of the second law of thermodynamics.

Robustness and physicality of solutions with a code are ideally defined by the basic properties of an algorithm. Upwind differencing is a good example where this happens (ideally). The reality is that achieving these goals usually takes a lot of tests and checks with corrective actions where the robustness or physicality is risked or violated. This makes for ugly algorithms and ugly codes. It makes purists very unhappy. Making them happy is the place where the engineering becomes science (or math).

A computational study is unlikely to lead to real scientific progress unless the software environment is convenient enough to encourage one to vary parameters, modify the problem, play around.

– Nick Trefethen

Flexible. You can write your code to solve one problem, if the problem is important enough, and you solve it well enough it might be a success. If your code can solve a lot of problems robustly (and physically) you might be even more successful. A code that is a jack-of-all-trades is usually a huge success. This requires a lot of thought, experience and effort to pull off. This usually gets into issues of meshing, material modeling, input, output, and generality in initial and boundary conditions. Usually the code gets messy in the process.

All that it is reasonable to ask for in a scientific calculation is stability, not accuracy. – Nick Trefethen

Accuracy. This is where things get interesting. For the most part accuracy is in conflict with every single characteristic we discuss. It is a huge challenge to both ends of the spectrum to robustness and efficiency. Accuracy makes codes more prone to failure (loss of robustness) and the failures have more modes. Accuracy is expensive and makes codes run longer. It can either cause more communication, or more complexity (or both). It makes numerical linear algebra harder and far more fragile. It makes boundary conditions, and initial conditions harder and encourages much more simplification of everything else. If it can be achieved accuracy is fantastic, but it is still a huge challenge to pull of.

The fundamental law of computer science: As machines become more powerful, the efficiency of algorithms grows more important, not less.

– Nick Trefethen

Efficiency. The code runs fast and uses the computers well. This is always hard to do, a beautiful piece of code that clearly describes an algorithm turns into a giant plate of spaghetti, but runs like the wind. To get performance you end up throwing out that wonderful inheritance hierarchy you were so proud of. To get performance you get rid of all those options that you put into the code. This requirement is also in conflict with everything else. It is also the focus of the funding agencies. Almost no one is thinking productively about how all of this (doesn’t) fit together. We just assume that faster supercomputers are awesome and better.

Efficiency. The code runs fast and uses the computers well. This is always hard to do, a beautiful piece of code that clearly describes an algorithm turns into a giant plate of spaghetti, but runs like the wind. To get performance you end up throwing out that wonderful inheritance hierarchy you were so proud of. To get performance you get rid of all those options that you put into the code. This requirement is also in conflict with everything else. It is also the focus of the funding agencies. Almost no one is thinking productively about how all of this (doesn’t) fit together. We just assume that faster supercomputers are awesome and better.

Q.E.D.

God help us.

It isn’t a secret that the United States has engaged in a veritable orgy of classification since 9/11. What is less well known is the massive implied classification through other data categories such as “official use only (OUO)”. This designation is itself largely unregulated as such is quite prone to abuse.

It isn’t a secret that the United States has engaged in a veritable orgy of classification since 9/11. What is less well known is the massive implied classification through other data categories such as “official use only (OUO)”. This designation is itself largely unregulated as such is quite prone to abuse.

Again something at work has inspired me to write. It’s a persistent theme among authors, artists and scientists regarding the concept of the fresh start (blank page, empty canvas, original idea). I think its worth considering how truly “fresh” these really are. This idea came up during a technical planning meeting where one of participants viewed this new project as being offered a blank page.

Again something at work has inspired me to write. It’s a persistent theme among authors, artists and scientists regarding the concept of the fresh start (blank page, empty canvas, original idea). I think its worth considering how truly “fresh” these really are. This idea came up during a technical planning meeting where one of participants viewed this new project as being offered a blank page. Once we stepped over that threshold, conflict erupted over the choices available with little conclusion. A large part of the issue was the axioms each person was working with. Across the board we all took a different set of decisions to be axiomatic. At some time in the past these “axioms” were choices, and became axiomatic through success. Someone’s past success becomes the model for future success, and the choices that led to that success become unstated decisions we are generally completely unaware of. These form the foundation of future work and often become culturally iconic in nature.

Once we stepped over that threshold, conflict erupted over the choices available with little conclusion. A large part of the issue was the axioms each person was working with. Across the board we all took a different set of decisions to be axiomatic. At some time in the past these “axioms” were choices, and became axiomatic through success. Someone’s past success becomes the model for future success, and the choices that led to that success become unstated decisions we are generally completely unaware of. These form the foundation of future work and often become culturally iconic in nature. Take the basic framework for discretization as an operative example: at Sandia this is the finite element method; at Los Alamos it is finite volumes. At Sandia we talk “elements”, at Los Alamos it is “cells”. From there we continued further down the proverbial rabbit hole to discuss what sort of elements (tets or hexes). Sandia is a hex shop, causing all sorts of headaches, but enabling other things, or simply the way a difficult problem was tackled. Tets would improve some things, but produce other problems. For some ,the decisions are flexible, for others there isn’t a choice, the use of a certain type of element is virtually axiomatic. None of these things allows a blank slate, all of them are deeply informed and biased toward specific decisions of made in some cases decades ago.

Take the basic framework for discretization as an operative example: at Sandia this is the finite element method; at Los Alamos it is finite volumes. At Sandia we talk “elements”, at Los Alamos it is “cells”. From there we continued further down the proverbial rabbit hole to discuss what sort of elements (tets or hexes). Sandia is a hex shop, causing all sorts of headaches, but enabling other things, or simply the way a difficult problem was tackled. Tets would improve some things, but produce other problems. For some ,the decisions are flexible, for others there isn’t a choice, the use of a certain type of element is virtually axiomatic. None of these things allows a blank slate, all of them are deeply informed and biased toward specific decisions of made in some cases decades ago. The other day I risked a lot by comparing the choices we’ve collectively made in the past as “original sin”. In other words what is computing’s original sin? Of course this is a dangerous path to tread, but the concept is important. We don’t have a blank slate; our choices are shaped, if not made by decisions of the past. We are living, if not suffering due to decisions made years or decades ago. This is true in computing as much as any other area.

The other day I risked a lot by comparing the choices we’ve collectively made in the past as “original sin”. In other words what is computing’s original sin? Of course this is a dangerous path to tread, but the concept is important. We don’t have a blank slate; our choices are shaped, if not made by decisions of the past. We are living, if not suffering due to decisions made years or decades ago. This is true in computing as much as any other area. In case you’re wondering about my writing habit and blog. I can explain a bit more. If you aren’t, stop reading. In the sense of authorship I force myself to face the blank page every day as an exercise in self-improvement. I read Charles Durhigg’s book “Habits” and realized that I needed better habits. I thought about what would make me better and set about building them up. I have a list of things to do every day, “write” “exercise” “walk” “meditate” “read” and so on.

In case you’re wondering about my writing habit and blog. I can explain a bit more. If you aren’t, stop reading. In the sense of authorship I force myself to face the blank page every day as an exercise in self-improvement. I read Charles Durhigg’s book “Habits” and realized that I needed better habits. I thought about what would make me better and set about building them up. I have a list of things to do every day, “write” “exercise” “walk” “meditate” “read” and so on. The blog is a concrete way of putting the writing to work. Usually, I have an idea the night before, and draft most of the thoughts during my morning dog walk (dogs make good motivators for walks). I still need to craft (hopefully) coherent words and sentences forming the theme. The blog allows me to publish the writing with a minimal effort, and forces me to take editing a bit more seriously. The whole thing is an effort to improve my writing both in style and ease of production.

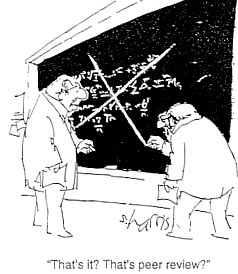

The blog is a concrete way of putting the writing to work. Usually, I have an idea the night before, and draft most of the thoughts during my morning dog walk (dogs make good motivators for walks). I still need to craft (hopefully) coherent words and sentences forming the theme. The blog allows me to publish the writing with a minimal effort, and forces me to take editing a bit more seriously. The whole thing is an effort to improve my writing both in style and ease of production. For some reason I’m having more “WTF” moments at work lately. Perhaps something is up, or I’m just paying attention to things. Yesterday we had a discussion about reviews, and people’s intense desire to avoid them. The topic came up because there have been numerous efforts to encourage and amplify technical review recently. There are a couple of reasons for this, mostly positive, but a tinge of negativity lies just below the surface. It might be useful to peel back the layers a bit and look at the dark underbelly.

For some reason I’m having more “WTF” moments at work lately. Perhaps something is up, or I’m just paying attention to things. Yesterday we had a discussion about reviews, and people’s intense desire to avoid them. The topic came up because there have been numerous efforts to encourage and amplify technical review recently. There are a couple of reasons for this, mostly positive, but a tinge of negativity lies just below the surface. It might be useful to peel back the layers a bit and look at the dark underbelly. I touched on this topic a couple of weeks ago (

I touched on this topic a couple of weeks ago ( The biggest problems with peer reviews are “bullshit reviews”. These are reviews that are mandated by organizations for the organization. These always get graded and the grades have consequences. The review teams know this thus the reviews are always on a curve, a very generous curve. Any and all criticism is completely muted and soft because of the repercussions. Any harsh critique even if warranted puts the reviewers (and their compensation for the review at risk). As a result of this dynamic, these reviews are quite close to a complete waste of time.

The biggest problems with peer reviews are “bullshit reviews”. These are reviews that are mandated by organizations for the organization. These always get graded and the grades have consequences. The review teams know this thus the reviews are always on a curve, a very generous curve. Any and all criticism is completely muted and soft because of the repercussions. Any harsh critique even if warranted puts the reviewers (and their compensation for the review at risk). As a result of this dynamic, these reviews are quite close to a complete waste of time. Because of the risk associated with the entire process, the organizations approach the review in an overly risk-averse manner, and control the whole thing. It ends up being all spin, and little content. Together with the dynamic created with the reviewers, the whole thing spirals into a wasteful mess that does no one any good. Even worse, the whole process has a corrosive impact on the perception of reviews. They end up having no up side; it is all down side and nothing useful comes out of them. All of this even though the risk from the reviews has been removed through a thoroughly incestuous process.

Because of the risk associated with the entire process, the organizations approach the review in an overly risk-averse manner, and control the whole thing. It ends up being all spin, and little content. Together with the dynamic created with the reviewers, the whole thing spirals into a wasteful mess that does no one any good. Even worse, the whole process has a corrosive impact on the perception of reviews. They end up having no up side; it is all down side and nothing useful comes out of them. All of this even though the risk from the reviews has been removed through a thoroughly incestuous process. An element in the overall dynamic is the societal image of external review as a sideshow meant to embarrass. The congressional hearing is emblematic of the worst sort of review. The whole point is grandstanding and/or destroying those being reviewed. Given this societal model, it is no wonder that reviews have a bad name. No one likes to be invited to their own execution.

An element in the overall dynamic is the societal image of external review as a sideshow meant to embarrass. The congressional hearing is emblematic of the worst sort of review. The whole point is grandstanding and/or destroying those being reviewed. Given this societal model, it is no wonder that reviews have a bad name. No one likes to be invited to their own execution. environment we find ourselves. First of all, people should be trained or educated in conducting, accepting and responding to reviews. Despite its importance to the scientific process, we are never trained how to conduct, accept or responds to a review (response happens a bit in a typical graduate education). Today, it is a purely experiential process. Next, we should stop including the scoring of reviews in any organizational “score”. Instead the quality of the review including the production or hard-hitting critique should be expected as a normal part of organizational functioning.

environment we find ourselves. First of all, people should be trained or educated in conducting, accepting and responding to reviews. Despite its importance to the scientific process, we are never trained how to conduct, accept or responds to a review (response happens a bit in a typical graduate education). Today, it is a purely experiential process. Next, we should stop including the scoring of reviews in any organizational “score”. Instead the quality of the review including the production or hard-hitting critique should be expected as a normal part of organizational functioning. I’m a progressive. In almost every way that I can imagine, I favor progress over the status quo. This is true for science, music, art, and literature, among other things. The one place where I tend to be status quo are work and personal relationships that form the foundation for my progressive attitudes. These foundations are formed by several “social contracts” that serve to define the roles and expectations. Without this foundation, the progress I so cherish is threatened because people naturally retreat to conservatism for stability.

I’m a progressive. In almost every way that I can imagine, I favor progress over the status quo. This is true for science, music, art, and literature, among other things. The one place where I tend to be status quo are work and personal relationships that form the foundation for my progressive attitudes. These foundations are formed by several “social contracts” that serve to define the roles and expectations. Without this foundation, the progress I so cherish is threatened because people naturally retreat to conservatism for stability. What I’ve come to realize is that the shortsighted, short is demolishing many of these social contracts –term thinking dominating our governance. Our social contracts are the basis of trust and faith in our institutions whether they are the rule of government, or the place we work. In each case we are left with a severe corrosion of the intrinsic faith once granted these cornerstones of public life. The cost is enormous, and may have created a self-perpetuating cycle of loss of trust precipitating more acts that undermine trust.

What I’ve come to realize is that the shortsighted, short is demolishing many of these social contracts –term thinking dominating our governance. Our social contracts are the basis of trust and faith in our institutions whether they are the rule of government, or the place we work. In each case we are left with a severe corrosion of the intrinsic faith once granted these cornerstones of public life. The cost is enormous, and may have created a self-perpetuating cycle of loss of trust precipitating more acts that undermine trust. What gets lost? Almost everything. Progress, quality, security, you name it. Our short-term balance sheet looks better, but our long-term prospects look dismal. The scary thing is that these developments help drive conservative thinking, which in turn drives these developments. As much as anything this could explain our Nation’s 50-year march to the right. We have taken the virtuous cycle we were granted, and developed a viscous cycle. It is a cycle that we need to get out of before it crushes our future.

What gets lost? Almost everything. Progress, quality, security, you name it. Our short-term balance sheet looks better, but our long-term prospects look dismal. The scary thing is that these developments help drive conservative thinking, which in turn drives these developments. As much as anything this could explain our Nation’s 50-year march to the right. We have taken the virtuous cycle we were granted, and developed a viscous cycle. It is a cycle that we need to get out of before it crushes our future. We got here through overconfidence and loss of trust can we get out of it by combining realism with trust in each other. Right now, the signs are particularly bad with nothing looking like realism, or trust being part of the current public discourse on anything.

We got here through overconfidence and loss of trust can we get out of it by combining realism with trust in each other. Right now, the signs are particularly bad with nothing looking like realism, or trust being part of the current public discourse on anything.

It seems to be a lot easier to metaphorically put our heads in the sand. A lot of the time we go to great lengths to convince ourselves of the opposite of the truth, to convince ourselves that we are the master’s of the universe. Instead we can only achieve the mastery we crave though the opposite. We should never consider our knowledge and capability to be flawless, but flawed and incomplete.

It seems to be a lot easier to metaphorically put our heads in the sand. A lot of the time we go to great lengths to convince ourselves of the opposite of the truth, to convince ourselves that we are the master’s of the universe. Instead we can only achieve the mastery we crave though the opposite. We should never consider our knowledge and capability to be flawless, but flawed and incomplete. The people applying calibrated models are often lauded as the models of success. The problems with this are deep and pernicious. We want to do much more than calibrate results, we want to understand and explore the unknown. The only way to do that is systematically uncover our failings, and shortcomings with a ken focus on exposing the limits we have. The practical success of calibrated modeling stands squarely in the way of pushing the bounds of knowledge.

The people applying calibrated models are often lauded as the models of success. The problems with this are deep and pernicious. We want to do much more than calibrate results, we want to understand and explore the unknown. The only way to do that is systematically uncover our failings, and shortcomings with a ken focus on exposing the limits we have. The practical success of calibrated modeling stands squarely in the way of pushing the bounds of knowledge.

We are encouraged by everything around us to work on things that are important. Given the intrinsic differences between the messaging we are given explicitly and implicitly, its hard to really decide what’s important. Of course, if you work on what’s important you will personally make a bit more money. You really make a lot of money if you work specifically in the money making industry…

We are encouraged by everything around us to work on things that are important. Given the intrinsic differences between the messaging we are given explicitly and implicitly, its hard to really decide what’s important. Of course, if you work on what’s important you will personally make a bit more money. You really make a lot of money if you work specifically in the money making industry…

These words are spoken whenever we go into planning “reportable” milestones in virtually every project I know about. If we are getting a certain chunk of money, we are expected to provide milestones that report our progress. It is a reasoned and reasonable thing, but the execution is horribly botched by the expectations that are grafted onto the milestone. Along with the guidance in the title of this post, we are told, “these milestones must always be successful, so choose your completion criteria carefully.” Along with this we make sure that these milestones don’t contain too much risk.

These words are spoken whenever we go into planning “reportable” milestones in virtually every project I know about. If we are getting a certain chunk of money, we are expected to provide milestones that report our progress. It is a reasoned and reasonable thing, but the execution is horribly botched by the expectations that are grafted onto the milestone. Along with the guidance in the title of this post, we are told, “these milestones must always be successful, so choose your completion criteria carefully.” Along with this we make sure that these milestones don’t contain too much risk. The real danger in the philosophy we have adopted is the creeping intrusion of mediocrity into everything we do. Nothing is important enough to take risks with. The thoughts expressed through these words are driving a mindless march toward mediocrity, once great research institutions are being thrust headfirst into the realm of milquetoast also-rans. The scientific and engineering superiority of the United States is leaving in lockstep with every successfully completed milestone built this way.

The real danger in the philosophy we have adopted is the creeping intrusion of mediocrity into everything we do. Nothing is important enough to take risks with. The thoughts expressed through these words are driving a mindless march toward mediocrity, once great research institutions are being thrust headfirst into the realm of milquetoast also-rans. The scientific and engineering superiority of the United States is leaving in lockstep with every successfully completed milestone built this way. Science depends on venturing bravely into the unknown, a task of inherent risk, and massive potential reward. The reward and risk are linked intimately; with nothing risked, nothing is gained. By making milestones both important and free of risk, we sap vitality from our work. Instead of wisely and competently stewarding the resources we are trusted with, they are squandered on work that is shallow and uninspired. Rather than being the best we can do, it becomes the thing we can surely do.

Science depends on venturing bravely into the unknown, a task of inherent risk, and massive potential reward. The reward and risk are linked intimately; with nothing risked, nothing is gained. By making milestones both important and free of risk, we sap vitality from our work. Instead of wisely and competently stewarding the resources we are trusted with, they are squandered on work that is shallow and uninspired. Rather than being the best we can do, it becomes the thing we can surely do. When push comes to shove, these milestones are always done, and always first in line for resource allocation. At the same time we have neutered them from the outset. The strategy (if you can call it that!) is self-defeating, and only yields the short-term benefit of the appearance of success. This appearance of success is believed to be necessary for continuing the supply of resources.

When push comes to shove, these milestones are always done, and always first in line for resource allocation. At the same time we have neutered them from the outset. The strategy (if you can call it that!) is self-defeating, and only yields the short-term benefit of the appearance of success. This appearance of success is believed to be necessary for continuing the supply of resources.

If you haven’t heard of “wicked problems” before it’s a concept that you should familiarize your self with. Simply put, a wicked problem is a problem that can’t be stated or defined without attempting to solve it. Even then your definition will be woefully incomplete. Wicked problems are recursive. Every attempt to solve the problem yields a better definition of the problem. They are the metaphorical onion where peeling back every layer produces another layer.

If you haven’t heard of “wicked problems” before it’s a concept that you should familiarize your self with. Simply put, a wicked problem is a problem that can’t be stated or defined without attempting to solve it. Even then your definition will be woefully incomplete. Wicked problems are recursive. Every attempt to solve the problem yields a better definition of the problem. They are the metaphorical onion where peeling back every layer produces another layer.

In code development this often takes the form of refactoring where the original design of part of the software is redone based on the experience gained through its earlier implementation. You understand the use of and form that the software should take once you’ve tried to write it (or twice or thrice or…). The point is that the implementation is better the second or third time based on the experience of the earlier work. In essence this is embracing failure in its proper role as a learning experience. A working, but ultimately failed form of the software is the best experience for producing a better piece of software.

In code development this often takes the form of refactoring where the original design of part of the software is redone based on the experience gained through its earlier implementation. You understand the use of and form that the software should take once you’ve tried to write it (or twice or thrice or…). The point is that the implementation is better the second or third time based on the experience of the earlier work. In essence this is embracing failure in its proper role as a learning experience. A working, but ultimately failed form of the software is the best experience for producing a better piece of software. This principle applies far more broadly to scientific endeavors. An archetypical scientific wicked problem is climate change not simply because the complexity of the scientific aspects of the problem, but also the political and cultural dynamics stirred up. In this way climate change connects back to the traditional wicked problems from the social sciences. A more purely scientific problem that is wicked is turbulence because of its enormous depth in terms of physics, engineering and math with an almost metaphysical level of intractability arising naturally. Turbulence is also connected to a wealth of engineering endeavors with immense economic consequences.

This principle applies far more broadly to scientific endeavors. An archetypical scientific wicked problem is climate change not simply because the complexity of the scientific aspects of the problem, but also the political and cultural dynamics stirred up. In this way climate change connects back to the traditional wicked problems from the social sciences. A more purely scientific problem that is wicked is turbulence because of its enormous depth in terms of physics, engineering and math with an almost metaphysical level of intractability arising naturally. Turbulence is also connected to a wealth of engineering endeavors with immense economic consequences.

Maintaining the perspective of wickedness as being fundamental is useful as it drives home the belief that your deep knowledge is intrinsically limited. The way that experts look at V&V (or any other wicked problem) is based on their own experience, but is not “right” or “correct” in and of itself. It is simply a workable structure that fits the way they have attacked the problem over time.

Maintaining the perspective of wickedness as being fundamental is useful as it drives home the belief that your deep knowledge is intrinsically limited. The way that experts look at V&V (or any other wicked problem) is based on their own experience, but is not “right” or “correct” in and of itself. It is simply a workable structure that fits the way they have attacked the problem over time.