A return to what I do best

For the first time in six years, I’m returning to writing about a topic within my professional field. This is where my true expertise lies, and frankly, it’s what I should be focusing on. If I were being cynical, I’d say this subject is entirely unrelated to work since it lacks any organizational support. It is clearly not our chosen strategy. Given that it’s neither a funded nor managed strategy, it’s essentially a hobby. Yet, it represents a significant missed opportunity for advancing several critical fields. Moreover, it highlights broader issues with our leadership and aversion to risk even when the rewards are large.

“Never was anything great achieved without danger.”

― Niccolo Machiavelli

Years ago when I blogged regularly, I often wrote one or two posts about upcoming talks. Some of my best work emerged from this process, which also enhanced the quality of my presentations. Writing is thinking; it forces deep reflection on a talk’s narrative and allows for refinement. By outlining ideas and considering supporting evidence, I could strengthen my arguments. Without this preparatory writing, my talks undoubtedly suffered. With this post, I hope to rectify this shortsighted but logical detour.

So, here goes!

“Don’t explain computers to laymen. Simpler to explain sex to a virgin.”

― Robert A. Heinlein

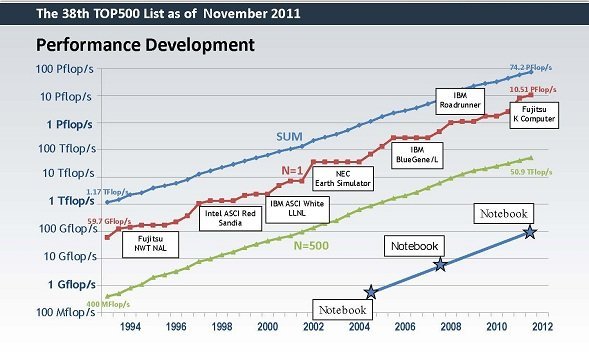

Algorithmic Impact and Moore’s Law

In recent years, the significance of algorithms in scientific computing has diminished considerably. Algorithms have historically been a substantial component of improving computing. They provide a performance boost beyond hardware acceleration. Unfortunately this decline in algorithmic impact coincides with the slowing of Moore’s Law. Moore’s law is the empirical observation that computing power doubles approximately every eighteen months leading to exponential increases. This rapid growth was fueled by a confluence of technological advancements integrated into hardware. However, this era of exponential growth ended about a decade ago. Instead of acknowledging this shift and adapting, it was met with an increased focus on hardware development. I’ve written extensively on this topic and won’t reiterate those points here.

“People who don’t take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year. People who do take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year.”

― Peter F. Drucker

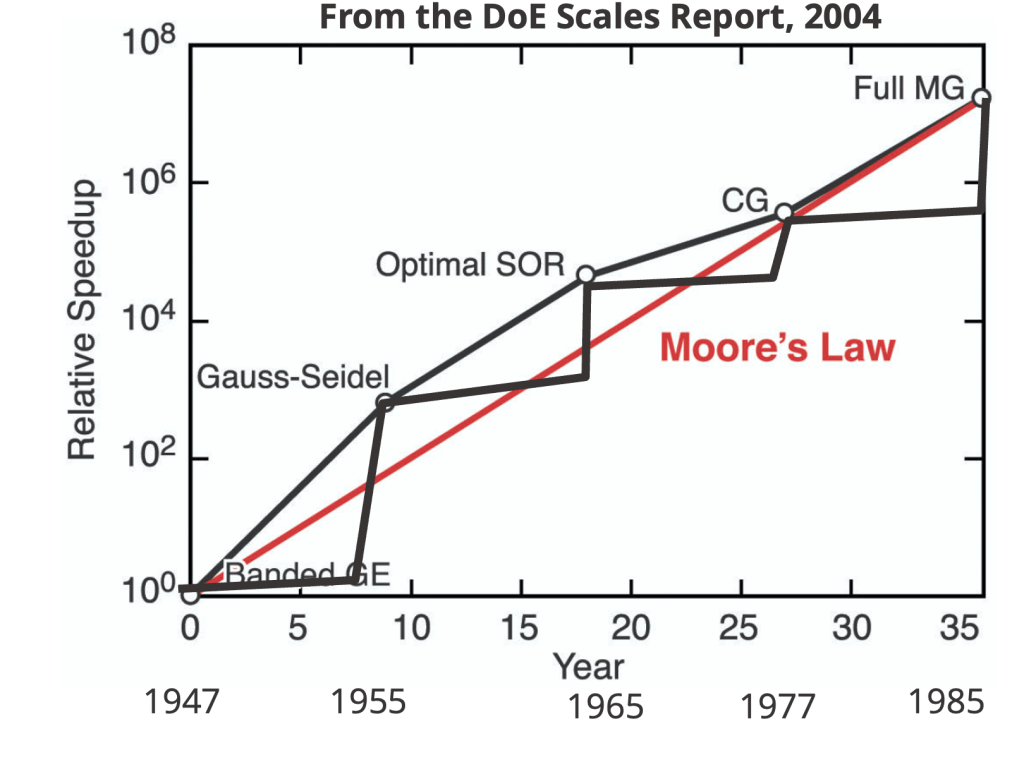

Simultaneously, we’ve neglected advancements in algorithms. Improving algorithms is inherently unpredictable.Breakthroughs are sporadic, defying schedules and plans. They emerge from ingenious solutions to previously insurmountable challenges and necessitate risk-taking. Such endeavors offer no guaranteed returns, a requirement often demanded by project managers. Instead, progress occurs in significant leaps after extended periods of apparent stagnation. Rather than a steady upward trajectory, advancements arrive in unpredictable bursts. This aversion to risk and the pursuit of guaranteed outcomes hinders the realization of algorithmic breakthroughs.

What is an algorithm?

An algorithm can be thought of as a recipe that instructs a computer to complete a task. Sorting a list is a classic algorithmic problem. Once a correct method is established, efficiency becomes the primary concern.

Algorithm efficiency is measured in terms of degrees of freedom, such as the length of a list. It is often expressed as a constant multiplied by the list length raised to a power (or its logarithm). This power significantly impacts efficiency,especially as the list grows. Consider the difference in effort for sorting a list of 100 items using linear, log-linear, and quadratic algorithms: 100, 460, and 10,000 operations, respectively. For a list of 1000 items, these numbers become 1000, 6900, and 1,000,000. We see differences in performance grow larger. As the list size increases, the impact of the constant factor before the scaling term diminishes. Note that generally, a linear algorithm has a larger constant than a quadratic one.

“An algorithm must be seen to be believed.”

As this example illustrates, algorithms are fundamentally powerful tools. Their efficiency scaling can dramatically reduce computational costs and accelerate calculations. This is just one of the many remarkable capabilities of algorithms. A large impact is they can significantly contributes to overall computing speed. Historically, the speedup achieved through algorithmic improvements has either matched or exceeded Moore’s Law. Even in the worst case, algorithms enhance and amplify the power of computer advancements. Our leaders seem to have ignored this. Certain incremental gains prime for project management with low risk are prioritized.

Algorithms for Scientific Computing

In the realm of scientific computing, the success of algorithms is most evident in linear algebra. For a long time during the early days of computing, algorithms kept pace with increasing computing speeds. This demonstrates that algorithms amplify the speed of computers. They complement each other, resulting in equally improved performance over a 40-year span.

Originally, linear algebra relied on dense algorithms with cubic work scaling (Gaussian elimination). These were replaced by relaxation and sparse-banded methods with quadratic scaling. Subsequently, Krylov methods, scaling to the three-halves or logarithmically with spectral methods, took over. Finally, in the mid-1980s, multigrid achieved linear scaling. Since then,there have been no further breakthroughs. Still from the 1940s to the mid-1980s, algorithms kept pace with hardware advancements. In this era the advances in hardware, which were massive was complimented by equal advances. In today’s words algorithms are a force multiplier.

“… model solved using linear programming would have taken 82 years to solve in 1988… Fifteen years later… this same model could be solved in roughly 1 minute, an improvement by a factor of roughly 43 million… a factor of roughly 1,000 was due to increased processor speed, … a factor of roughly 43,000 was due to improvements in algorithms!”

– Designing a Digital Future: Federally Funded R&D in Networking and Information Technology

Examples of algorithmic impact are prevalent throughout scientific computing. In optimization, interior point methods dramatically accelerated calculations, outpacing hardware advancements for a period. More recently, the influence of algorithms has become apparent in private sector research. A prime example is Google’s PageRank algorithm. This revolutionized internet search. Once you used Google to search you never went back to Altavista or Yahoo. In the process it also laid the foundation for one of the world’s most influential and prosperous companies. Today Google has a market cap in excess of 2 trillion dollars.

“When people design web pages, they often cater to the taste of the Google search algorithm rather than to the taste of any human being.”

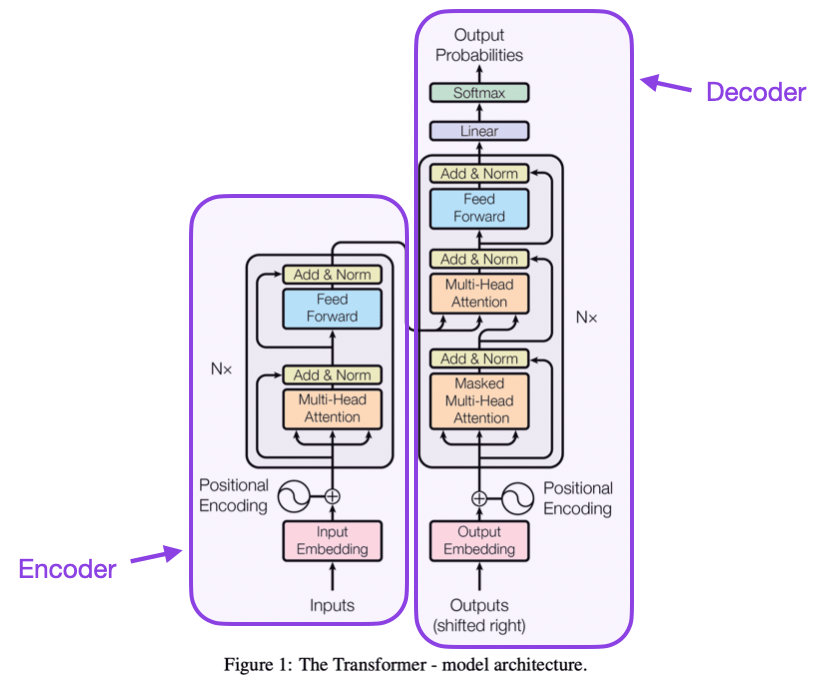

More recently, another algorithm has revolutionized the tech world: the transformer. This breakthrough was instrumental in the recent developments of large language models (LLMs). These have reshaped the technology landscape in the past couple years. The transformer’s impact is multifaceted. Most superficially, it excels at consuming and processing data in vector form, aligning perfectly with modern GPU hardware. This synergy has propelled NVIDIA to unprecedented heights of corporate success (lifting it to trillion dollar market cap).

Less obvious, but equally significant, is the transformer’s influence on LLM behavior. Unlike previous models that processed data sequentially, the transformer operates on vector data chunks, enabling the network to consider larger contexts. This represents a quantum leap in LLM capabilities and behavior.

A cautionary tale emerges from the transformer’s history. Google pioneered the algorithm, but others reaped the primary benefits. This highlights a common challenge with algorithmic advancements: those making the initial breakthrough may not see the principal benefits. Moreover, the vision to develop an algorithm often differs from the vision to optimize its use. This presents a persistent hurdle for project managers. Project manager are relentlessly myopic.

“Computer Science is no more about computers than astronomy is about telescopes”

― Edsger Wybe Dijkstra

It is well known that the power of algorithms is on par with the impact of hardware improvements. However, a key distinction lies in the predictability of progress. Algorithmic advancements stem from discovery and inspiration. These are elements that defy the quarterly planning cycles prevalent in contemporary research. An intolerance for failure hinders algorithmic progress. As exemplified by the transformer, algorithms often benefit organizations beyond their originators. Success lies in adapting to the capabilities of these innovative tools.

Algorithms I really care about

My professional focus lies in developing methods to solve hyperbolic conservation laws. The nature of these equations offers significant potential for algorithmic improvements, a fact often overlooked in current research directions. This oversight stems from a lack of clarity about the true measures of success in numerical simulations. The fundamental objective is to produce highly accurate solutions while minimizing computational effort. This is to be achieved while maintaining robustness, flexibility, and physical correctness.

“The scientific method’s central motivation is the ubiquity of error – the awareness that mistakes and self-delusion can creep in absolutely anywhere and that the scientist’s effort is primarily expended in recognizing and rooting out error.”

– David Donoho et al. (2009)

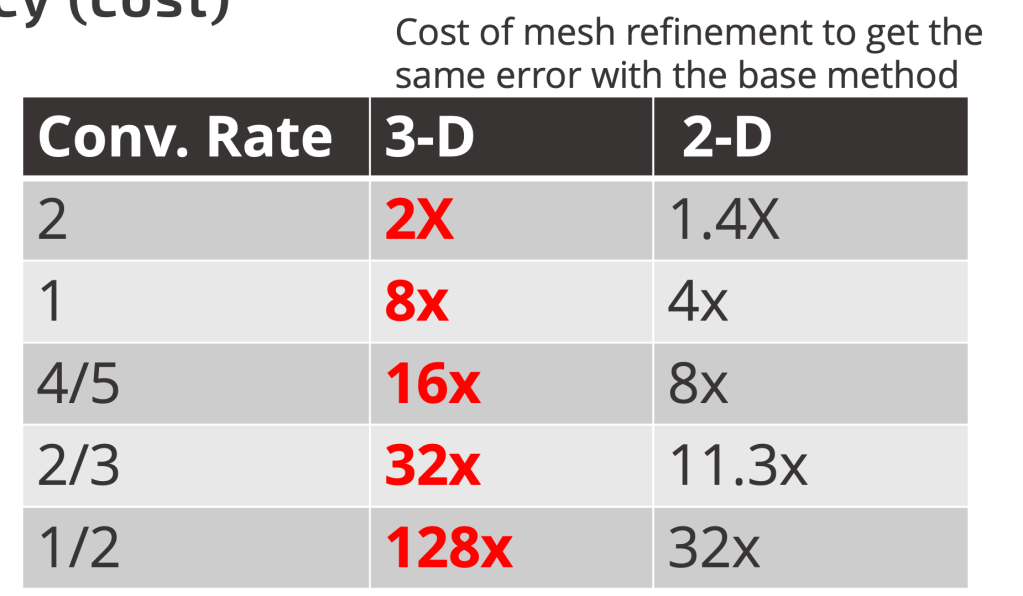

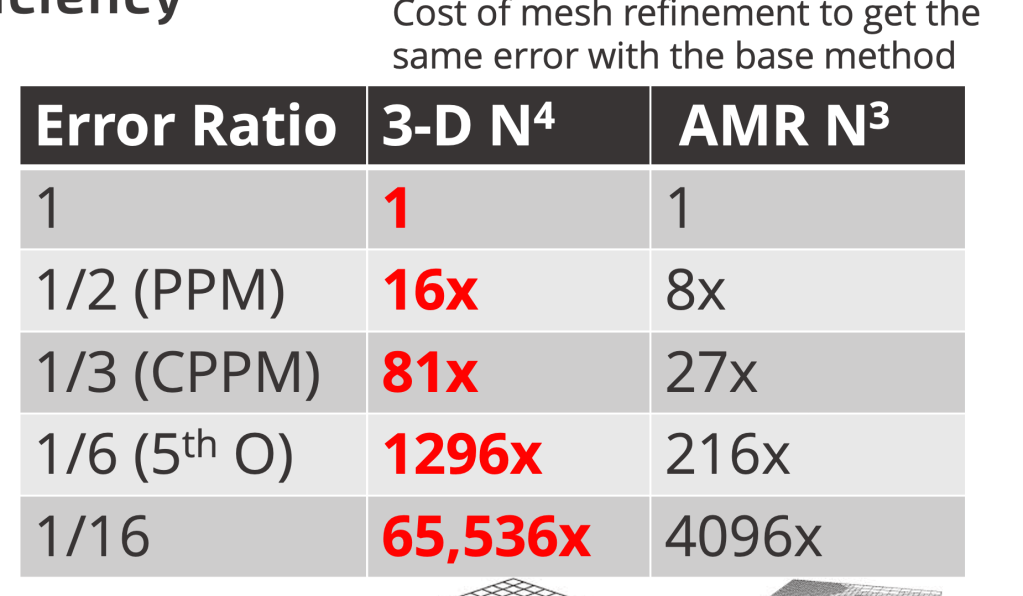

Achieving an unambiguous measure of solution accuracy uses a process known as code verification. A common misconceptions about code verification is its focus on bug finding rather than precise error quantification. It is equally important to understand how computational effort reduces error. Mesh refinement is a standard approach adding more degrees of freedom. This increases the cost in a well defined way that depends on the dimensionality of the problem. For a one-dimensional explicit calculation, computational cost scales quadratically with decreasing mesh size due to the linear relationship between time step and mesh size. In two and three dimensions, this scaling becomes cubic and quartic, respectively.

Code verification reveals both precise error (given an exact solution) and convergence rate. For problems with discontinuities like shock waves, the convergence rate is inherently limited to first order, regardless of the method used. This rate often falls below one due to numerical behavior near linear discontinuities. For simplicity, we will focus on the implications of first-order convergence. Given a fixed convergence rate, error accuracy becomes paramount. Furthermore as the convergence rate diminishes the base algorithmic accuracy grows in impact.

While testing is standard practice in hyperbolic conservation law research, it is often inconsistent. Accuracy is typically reported for smooth problems where high-order accuracy can be achieved. However, once smoothness is lost and accuracy drops to first order or less, reporting error ceases. Notably the problems with shock waves are the reason we study these equations. The Sod shock tube is a common test case, but results are presented graphically without quantitative comparison. This reflects a common misconception that qualitative assessments suffice after shock formation, disregarding the significance of accuracy differences.

“What’s measured improves”

– Peter Drucker

Because the order of accuracy is limited to first order, even small differences in accuracy become more significant. For standard methods, these base accuracy differences can easily range from two to four times, dramatically impacting computational cost to achieve an error level. Minimizing the effort required to achieve a desired accuracy level is crucial. The reason is simple: accuracy matters more as the convergence rate decreases. The lower the convergence rate, the greater the impact of accuracy on overall performance.

The algorithmic payoff

Consider a method that halves the error for double the cost at a given mesh resolution. We break even with second-order accuracy, a mesh half the size of the original is required in one dimension. For third and fourth-order accuracy, the break-even points shift to two and three dimensions, respectively. These dynamics change entirely when considering the fixed first-order accuracy imposed by mathematical theory.

“The fundamental law of computer science: As machines become more powerful, the efficiency of algorithms grows more important, not less.“

– Nick Trefethen

In one dimension, the less accurate method is twice as costly for the same error. This factor escalates to four times in two dimensions and eight times in three dimensions. As accuracy disparities grow, the advantage of higher accuracy expands exponentially. A sixteen-fold error difference can lead to a staggering 65,000-fold cost advantage in 3D. Consequently, even significantly more expensive methods can offer substantial benefits. Essentially the error difference amortizes the algorithmic cost. Despite this potential, the field remains entrenched in decades-old,low-accuracy approaches. This stagnation is rooted in a fear of failure and short-term thinking, with long-term consequences.

If failure is not an option, then neither is success.

― Seth Godin

This entire dynamic is inextricably linked to a shift toward short-term focus and risk aversion. Long-term objectives are essential for algorithmic advancement, demanding vision and persistence. The capacity to withstand repeated failures while maintaining faith in eventual success is equally critical. Unfortunately, today’s obsession with short-term project management stifles progress at its inception. This myopic approach is profoundly detrimental to long-term advancement.

References

Lax, Peter D., and Robert D. Richtmyer. “Survey of the stability of linear finite difference equations.” Communications on pure and applied mathematics 9, no. 2 (1956): 267-293.

Majda, Andrew, and Stanley Osher. “Propagation of error into regions of smoothness for accurate difference approximations to hyperbolic equations.” Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 30, no. 6 (1977): 671-705.

Banks, Jeffrey W., T. Aslam, and William J. Rider. “On sub-linear convergence for linearly degenerate waves in capturing schemes.” Journal of Computational Physics 227, no. 14 (2008): 6985-7002.

Lax, Peter D. “Accuracy and resolution in the computation of solutions of linear and nonlinear equations.” In Recent advances in numerical analysis, pp. 107-117. Academic Press, 1978.

Page, Lawrence, Sergey Brin, Rajeev Motwani, and Terry Winograd. The pagerank citation ranking: Bring order to the web. Technical report, Stanford University, 1998.

Vaswani, Ashish, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. “Attention is all you need.” Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

Sod, Gary A. “A survey of several finite difference methods for systems of nonlinear hyperbolic conservation laws.” Journal of computational physics 27, no. 1 (1978): 1-31.

Greenough, J. A., and W. J. Rider. “A quantitative comparison of numerical methods for the compressible Euler equations: fifth-order WENO and piecewise-linear Godunov.” Journal of Computational Physics 196, no. 1 (2004): 259-281.

Rider, William J., Jeffrey A. Greenough, and James R. Kamm. “Accurate monotonicity-and extrema-preserving methods through adaptive nonlinear hybridizations.” Journal of Computational Physics 225, no. 2 (2007): 1827-1848.

All true, but the diagnosis is generalizable to nearly all technical knowledge based work in disparate fields. I began my career as a computational mathematician 35 years ago specializing in optimizing CFD codes and computing systems, together. I stopped doing that 25 years ago because the salaries paid were slowly diminishing to practical zero. I originally started out as a chemical engineer though, and my spouse as well, and she’s ending her career soon as a packaging engineer. Along the way management has successfully destroyed any possibility of actually solving problems in house. So modifications/bug fixes to installed machinery and processes, most of which are driven by software, must be outsourced to entities external to the firm. The cost of the external expertise is so expensive that only in the most extreme cases is it deemed to be justified. So the machinery/processes are run in the stupidest/least efficient possible way.

Your complaint in this post boils down to management doesn’t actually want to pay employees to maintain eg your expertise. The risk aversion you discuss is I think more broadly viewed by management as a tradeoff between being dependent on in house expertise (which is potentially ephemeral) vs. just relying on off the shelf consultants/tech. This intentionally prejudices the available solution spaces within the org for technical problems to be restricted to the lowest possible level of expertise. And thus *your* algorithm space ends up as the dumbest possible, consistent with management being able to demonstrate short term success that is in turn consistent with parameters *management* values.

It seems incredibly short sighted and suicidal but things can go on for a long time, until they don’t. Consider Boeing.

Thanks for the comment. I’ll just note that my expertise is applied to work for the federal government. Its part of our national nuclear deterrent. So by not maintaining the expertise of me and my colleagues the deterrent is being undermined. Yes Boeing is a good example and basically a canary in the coal mine. Its problems are repeated all over.

Thanks Bill, agreed about the deterrent business.

Fresh out in 1989 I spent 5 years at NAS/NASA Ames, and then a short jaunt at Sandia/Livermore. 30 years ago those places were absolutely great for undirected (bottom-up) research, as long as you could make the technical case that practical *implementable* improvements in the areas of interest were (at least somewhat) likely. I have no idea what they’re like now, nor do I know anything about the NM labs, though I did visit them at the time.

The on-site contractors at the time were very much part of the research teams, so contractor management basically ceded actual management of day-to-day (really month-to-month) tasks to the government team leaders, who were all in on build the worlds best, and be efficient about it. I started out as a contractor and was able to spend a fair amount of time in the Stanford libraries and attend talks from IBM/HP/PARC/SUN researchers.

Earlier though when I was an undergraduate at GaTech, I co-oped at a GE nuclear fuels facility in the health physics department, and the atmosphere, 8 years earlier from NASA, was much the same. Bring in what you need and perform whatever actions are required to make the facility safe, in practicable state-of-the-art terms.

AFAICT, that sort of technical working environment where local expertise was encouraged to flourish and initiate direction might be pretty rare these days.

I have no idea where things are going but my daughter is well into her PhD and… I shall see what she sees a couple of years from now.

Since I started at Los Alamos in ’89 we are about the same age. Things there were fantastic for a decade or so. Then things unraveled and have continued to for the past 20+ years. A lot of this comes down to “safety” in practical terms, but also being “safe” from failure. If you can’t fail, you can’t succeed either.

Pingback: Code Verification Needs a Refresh | The Regularized Singularity