Judge a man by his questions rather than by his answers.

― Voltaire

In thinking about what makes work good for me, I explored an element of the creative process for me revolving around answering questions. If one doesn’t have the right question, the work isn’t framed correctly and progress will stall. A thing to consider in this frame of reference is what makes a good question? This itself is an excellent question! The quality of the question makes a great difference in framing the whole scientific enterprise, and can either lead to bad places of “knowledge cul-de-sacs” or open stunning vistas of understanding. Where you end up depends on the quality of the question you answer. Success depends far more on asking the right question than answering the question originally put to you (or you put to yourself).

truth, like gold, is to be obtained not by its growth, but by washing away from it all that is not gold.

― Leo Tolstoy

A great question is an achievement in itself although rarely viewed as such. More often than not little of the process of work goes into asking the right question. Often the questions we ask are highly dependent upon foundational assumptions that are never questioned. While assumptions about existing knowledge are essential, finding the weak or invalid assumptions is often the key to progress. These assumptions are wonderful for simplifying work, but also inhibit progress. Challenging assumptions is one of the most valuable things to do. Heretical ideas are fundamental to progress; all orthodoxy began as heresy. If the existing assumptions hold up under the fire of intense scrutiny they gain greater credibility and value. If they fall, new horizons are opened up to active exploration.

A great question is an achievement in itself although rarely viewed as such. More often than not little of the process of work goes into asking the right question. Often the questions we ask are highly dependent upon foundational assumptions that are never questioned. While assumptions about existing knowledge are essential, finding the weak or invalid assumptions is often the key to progress. These assumptions are wonderful for simplifying work, but also inhibit progress. Challenging assumptions is one of the most valuable things to do. Heretical ideas are fundamental to progress; all orthodoxy began as heresy. If the existing assumptions hold up under the fire of intense scrutiny they gain greater credibility and value. If they fall, new horizons are opened up to active exploration.

If we have no heretics we must invent them, for heresy is essential to health and growth.

― Yevgeny Zamyatin

It goes without saying that important questions are good ones. Defining importance is tricky business. There are plenty of important questions that lead nowhere “what’s the meaning of life?” or we simply can’t answer using existing knowledge, “is faster than light travel possible?” On the other hand we might do well to break these questions down to something more manageable that might be attacked, “is the second law of thermodynamics responsible for life?” or “what do subatomic particles tell us about the speed of light?” Part of the key to good scientific progress is threading the proverbial needle of important, worthy and possible to answer. When we manage to ask an important, but manageable question, we serve progress well. Easy questions are not valuable, but are attractive due to their lack of risk and susceptibility to management and planning. Sometimes the hardest part of the process is asking the question, and a well-defined and chosen problem can be amenable to trivial resolution. It turns out to be an immensely difficult task with lots of hard work to get to that point.

I have benefited mightily from asking some really great questions in the past. These  questions have led to the best research, and most satisfying professional work I’ve done. I would love to recapture this spirit of work again, with good questioning work feeling almost quaint in today’s highly over-managed climate. One simple question occurred in my study of efficient methods for solving the equations of incompressible flow. I was using a pressure projection scheme, which involves solving a Poisson equation at least once, if not more than once a time step. The most efficient way to do this involved using the multigrid method because of its algorithmic scaling being linear. The Poisson equation involves solving a large sparse system of linear equations, and the solution of linear equations scales with powers of the number of equations. Multigrid methods have the best scaling thought to be possible (I’d love to see this assumption challenged and sublinear methods discovered, I think they might well be possible).

questions have led to the best research, and most satisfying professional work I’ve done. I would love to recapture this spirit of work again, with good questioning work feeling almost quaint in today’s highly over-managed climate. One simple question occurred in my study of efficient methods for solving the equations of incompressible flow. I was using a pressure projection scheme, which involves solving a Poisson equation at least once, if not more than once a time step. The most efficient way to do this involved using the multigrid method because of its algorithmic scaling being linear. The Poisson equation involves solving a large sparse system of linear equations, and the solution of linear equations scales with powers of the number of equations. Multigrid methods have the best scaling thought to be possible (I’d love to see this assumption challenged and sublinear methods discovered, I think they might well be possible).

As problems with incompressible flows become more challenging such as involving large density jumps, the multigrid method begins to become fragile. Sometimes the optimal scaling breaks down, or the method fails altogether. I encountered these problems, but found that other methods like conjugate gradient could still solve the problems. The issue is that the conjugate gradient method is less efficient in its scaling than multigrid. As a result as problems become larger, the proportion of the solution time spent solving linear equations grows ever larger (the same thing is happening now to multigrid because of the cost of communication on modern computers). I posed the question of whether I could get the best of both methods, the efficiency with the robustness? Others were working on the same class of problems, and all of us found the solution. Combine the two methods together, effectively using a multigrid method to precondition the conjugate gradient method. It worked like a charm; it was both simple and stunningly effective. This approach has become so standard now that people don’t even think about it, its just the status quo.

As a result as problems become larger, the proportion of the solution time spent solving linear equations grows ever larger (the same thing is happening now to multigrid because of the cost of communication on modern computers). I posed the question of whether I could get the best of both methods, the efficiency with the robustness? Others were working on the same class of problems, and all of us found the solution. Combine the two methods together, effectively using a multigrid method to precondition the conjugate gradient method. It worked like a charm; it was both simple and stunningly effective. This approach has become so standard now that people don’t even think about it, its just the status quo.

At this point it is useful to back up and discuss a key aspect of the question-making process essential to refining a question into something productive. My original question was much different, “how can I fix multigrid?” was the starting point. I was working from the premise that multigrid was optimal and fast for easier problems, and conjugate gradient was robust, but slower. A key part of the process was a reframing the question. The question I ended up attacking was “can I get the positive attributes of both algorithms?” This changed the entire approach to solving the problem. At first, I tried switching between the two methods depending on the nature of the linear problem. This was difficult to achieve because the issues with the linear system are not apparent under inspection.

The key was moving from considering the algorithms as different options whole cloth, to combining them. The solution involved putting one algorithm inside the other. As it turns out the most reasonable and powerful way to do this is make multigrid a preconditioner for conjugate gradient. The success of the method is fully dependent on the characteristics of both algorithms. When multigrid is effective by itself, the conjugate gradient method is effectively innocuous. When multigrid breaks down, the conjugate gradient method picks up the pieces, and delivers robustness along with the linear scaling of multigrid. A key aspect of the whole development is embracing an assault on a philosophical constraint in solving linear systems. At the outset of this work these two methods were viewed as competitors. One worked on one or the other, and the two communities do not collaborate, or even talk to each other. They don’t like each other. They have different meetings, or different sessions at the same meeting. Changing the question allows progress, and is predicated on changing assumptions. Ultimately, the results win and the former feud fades into memory. In the process I helped create something wonderful and useful plus learned a huge amount of numerical (and analytical) linear algebra.

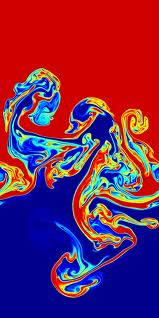

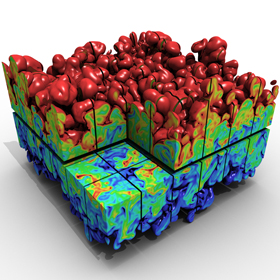

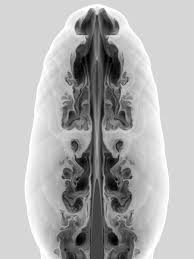

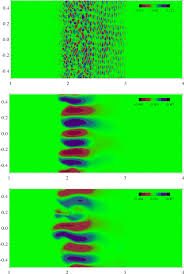

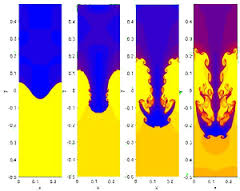

The second great question I’ll point to involved the study of modeling turbulent flows with what has become known as implicit large eddy simulation. Starting in the early 1990’s there was a stunning proposition that certain numerical methods seem to automatically (auto-magically) model aspects of turbulent flows. While working at Los Alamos and learning all about a broad class of nonlinearly stable methods, the claim that they could model turbulence caught my eye (I digested it, but fled in terror from turbulence!). Fast forward a few years and combine this observation with a new found interest in modeling turbulence, and a question begins to form. In learning about turbulence I digested a huge amount of theory regarding the physics, and our approaches to modeling it. I found large eddy simulation to be extremely interesting although aspects of the modeling were distressing. The models that worked well were performed poorly on the structural details of turbulence, and the models that matched the structure of turbulence were generally unstable. Numerical methods for solving large eddy simulation were generally based on principles vastly different than those I worked on, which were useful for solving Los Alamos’ problems.

The second great question I’ll point to involved the study of modeling turbulent flows with what has become known as implicit large eddy simulation. Starting in the early 1990’s there was a stunning proposition that certain numerical methods seem to automatically (auto-magically) model aspects of turbulent flows. While working at Los Alamos and learning all about a broad class of nonlinearly stable methods, the claim that they could model turbulence caught my eye (I digested it, but fled in terror from turbulence!). Fast forward a few years and combine this observation with a new found interest in modeling turbulence, and a question begins to form. In learning about turbulence I digested a huge amount of theory regarding the physics, and our approaches to modeling it. I found large eddy simulation to be extremely interesting although aspects of the modeling were distressing. The models that worked well were performed poorly on the structural details of turbulence, and the models that matched the structure of turbulence were generally unstable. Numerical methods for solving large eddy simulation were generally based on principles vastly different than those I worked on, which were useful for solving Los Alamos’ problems.

Having methods I worked on for codes that do solve our problems also model turbulence is tremendously attractive. The problem is the seemingly magical nature of this modeling. Being magical does not endow the modeling with confidence. The question that we constructed a research program around was “can we explain the magical capability of numerical methods with nonlinear stability to model turbulence?” We combined the observation that a broad class of methods seemed to provide effective turbulence modeling (or the universal inertial range physics). Basically the aspects of turbulence associated with the large-scale hyperbolic parts of the physics were captured. We found that it is useful to think of this as physics-capturing as an extension of shock-capturing. The explanation is technical, but astoundingly simple.

Upon study of the origins of large eddy simulation we discovered that the origins of the method were the same as shock capturing methods. Once the method was developed it evolved into its own subfield with its own distinct philosophy, and underlying assumptions. These assumptions had become limiting and predicated on a certain point-of-view. Shock capturing had also evolved in a different direction. Each field focused on different foundational principles and philosophy becoming significantly differentiated. For the most part they spoke different scientific languages. It was important to realize that their origins were identical with the first shock capturing method being precisely the first subgrid model for large eddy simulation. A big part of our research was bridging the divides that had developed over almost five decades and learn to translate from one language to the other.

We performed basic numerical analysis of nonlinearly stable schemes using a technique that produced the nonlinear truncation error. A nonlinear analysis is vital here. This uses a technique known as modified equation analysis. The core property of the methods empirically known to be successful in capturing the physics of turbulence is conservation (control volume schemes). It turns out that the nonlinear truncation error for a control volume method for a quadratic nonlinearity produces the fundamental scaling seen in turbulent flows (and shocks for that matter). This truncation error can be destabilizing for certain flow configurations, effectively being anti-dissipative. The nonlinear stability method keeps the anti-dissipative terms under control, producing physically relevant solutions (e.g., entropy-solutions).

A key observation makes this process more reasoned and connected to the traditional large eddy simulation community. The control volume term matches the large eddy simulation models that produce good structural simulations of turbulence (the so-called scale similarity model). The scale similarity model is unstable with classical numerical methods. Nonlinear stability fixes this problem with aplomb. We use as much scale similarity as possible without producing unphysical or unstable results. This helps explain why a disparate set of principles used to produce nonlinear stability provides effective turbulence modeling. Our analysis also shows why some methods are ineffective for turbulence modeling. If the dissipative stabilizing effects are too large and competitive with the scale similarity term, the nonlinear stability is ineffective as a turbulence model.

It is dangerous to be right in matters on which the established authorities are wrong.

― Voltaire

I should spend some time on some bad questions as examples of what shouldn’t be pursued. One prime example is offered as a seemingly wonderful question, the existence of solutions to the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. The impetus for this question is the bigger question of can we explain, predict or understand fluid turbulence? This problem is touted as a fundamental building block in this noble endeavor. The problem is the almost axiomatic belief that turbulence is contained within this model. The key term is incompressible, which renders the equations unphysical on several key accounts: it gives the system infinite speed of propagation, and divorces the equations from thermodynamics. Both features sever the ties of the equations from the physical universe. The arguing point is whether these two aspects disqualify it from addressing turbulence. I believe the answer is yes.

I should spend some time on some bad questions as examples of what shouldn’t be pursued. One prime example is offered as a seemingly wonderful question, the existence of solutions to the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. The impetus for this question is the bigger question of can we explain, predict or understand fluid turbulence? This problem is touted as a fundamental building block in this noble endeavor. The problem is the almost axiomatic belief that turbulence is contained within this model. The key term is incompressible, which renders the equations unphysical on several key accounts: it gives the system infinite speed of propagation, and divorces the equations from thermodynamics. Both features sever the ties of the equations from the physical universe. The arguing point is whether these two aspects disqualify it from addressing turbulence. I believe the answer is yes.

In my opinion this question should have been rejected long ago based on the available evidence. Given that our turbulence theory is predicated on the existence of singularities in ideal flows, and the clear absence of such singularities in the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations, we should reject the notion that turbulence is contained in them. Despite this evidence, the notion that turbulence is contained whole cloth in these unphysical equations remains unabated. It is treated as axiomatic. This is an example of an assumption that has out lived its usefulness. It will eventually be tossed out, and progress will bloom the path of its departure. One of the key things missing from turbulence is a connection to thermodynamics. Thermodynamics is such a powerful scientific concept and for it to be so absent from turbulence is a huge gap. Turbulence is a fundamental dissipative process and the second law is grounded on dissipation. The two should be joined into a coherent whole allowing unity and understanding to reign where confusion is supreme today.

Another poorly crafted question revolves around the current efforts for exascale class computers for scientific computing. There is little doubt that an exascale computer would be useful for scientific computing. A better question is what is the most beneficial way to push scientific computing forward? How can we make scientific computing more impactful in the real world? Can the revolution of mobile computing be brought to science? How can we make computing (really modeling and simulation) more effective in impacting scientific progress? Our current direction is an example of crafting an obvious question, with an obvious answer, but failing to ask a more cutting and discerning question. The consequence of our unquestioning approach to science will be wasted money and stunted progress.

Another poorly crafted question revolves around the current efforts for exascale class computers for scientific computing. There is little doubt that an exascale computer would be useful for scientific computing. A better question is what is the most beneficial way to push scientific computing forward? How can we make scientific computing more impactful in the real world? Can the revolution of mobile computing be brought to science? How can we make computing (really modeling and simulation) more effective in impacting scientific progress? Our current direction is an example of crafting an obvious question, with an obvious answer, but failing to ask a more cutting and discerning question. The consequence of our unquestioning approach to science will be wasted money and stunted progress.

Trust is equal parts character and competence… You can look at any leadership failure, and it’s always a failure of one or the other.

― Stephen M.R. Covey

This gets at a core issue with how science is managed today. Science has never been managed more tightly and becoming more structurally mismanaged. The tight management of science as exemplified by the exascale computing efforts is driven by an overwhelming lack of trust in those doing science. Rather than ask people open-ended questions subject to refinement through learning, we ask scientists to work on narrowly defined programs with preconceived outcomes. The reality is that any breakthrough, or progress for that matter will take a form not envisioned at the outset of the work. Any work that pushes mankind forward will take a form not foreseeable. By managing so tightly and constraining work, we are predestining the outcomes to be stunted and generally unworthy of the effort put into them.

Whether you’re on a sports team, in an office or a member of a family, if you can’t trust one another there’s going to be trouble.

― Stephen M.R. Covey

This is seeded by an overwhelming lack of t rust in people and science. Trust is a powerful concept and its departure from science has been disruptive and expensive. Today’s scientists are every bit as talented and capable as those of past generations, but society has withdrawn its faith in science. Science was once seen as a noble endeavor that embodied the best in humanity, but generally not so today. Progress in the state of human knowledge produced vast benefits for everyone and created the foundation for a better future. There was a sense of an endless frontier constantly pushing out and providing wonder and potential for everyone. This view was a bit naïve and overlooked the maxim that human endeavors in science are neither good or bad, producing outcomes dependent upon the manner of their use. For a variety of reasons, some embedded within the scientific community, the view of society changed and the empowering trust was withdrawn. It has been replaced with suspicion and stultifying oversight.

rust in people and science. Trust is a powerful concept and its departure from science has been disruptive and expensive. Today’s scientists are every bit as talented and capable as those of past generations, but society has withdrawn its faith in science. Science was once seen as a noble endeavor that embodied the best in humanity, but generally not so today. Progress in the state of human knowledge produced vast benefits for everyone and created the foundation for a better future. There was a sense of an endless frontier constantly pushing out and providing wonder and potential for everyone. This view was a bit naïve and overlooked the maxim that human endeavors in science are neither good or bad, producing outcomes dependent upon the manner of their use. For a variety of reasons, some embedded within the scientific community, the view of society changed and the empowering trust was withdrawn. It has been replaced with suspicion and stultifying oversight.

When I take a look at the emphasis in currently funded work, we see narrow vistas. There is a generally myopic and tactical view of everything. Long-term prospects, career development and broad objectives are obscured by management discipline and formality. Any sense of investment in the long-term is counter to the current climate. Nothing speaks more greatly to the overwhelming myopia is the attitude toward learning and personal development. It is only upon realizing that learning and research are essentially the same thing does it start to become clear how deeply we are hurting the scientific community. We have embraced a culture that is largely unquestioning with a well-scripted orthodoxy. Questions are seen as heresy against the established powers and punished. For most, learning is the acquisition of existing knowledge and skills. Research is learning new knowledge and skills. Generally speaking, those who have achieved mastery of their fields execute research. Since learning and deep career development is so hamstrung by our lack of trust, fewer people actually achieve the sort of mastery needed for research. The consequences for society are profound because we can expect progress to be thwarted.

Curiosity is more important than knowledge.

― Albert Einstein

One clear way to energize learning, and research is encouraging questioning. After encouraging a questioning attitude and approach to conducting work, we need to teach people to ask good questions, going back and refining questions, as better understanding is available. We need to identify and overcome assumptions subjecting them to unyielding scrutiny. The learning, research and development environment is equivalent to a questioning environment. By creating an unquestioning environment we short-circuit everything leading to progress, and ultimately cause much of the creative engine of humanity to stall. We would be well served by embracing the fundamental character of humanity as a creative, progressive and questioning species. These characteristics are parts of the best that people have to offer and allow each of us to contribute to the arc of history productively.

Curiosity is the engine of achievement.

― Ken Robinson

Brandt, Achi. “Multi-level adaptive solutions to boundary-value problems.” Mathematics of computation 31, no. 138 (1977): 333-390.

Briggs, William L., Van Emden Henson, and Steve F. McCormick. A multigrid tutorial. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2000.

Kershaw, David S. “The incomplete Cholesky—conjugate gradient method for the iterative solution of systems of linear equations.” Journal of Computational Physics 26, no. 1 (1978): 43-65.

Melson, N. Duane, T. A. Manteuffel, and S. F. Mccormick. “The Sixth Copper Mountain Conference on Multigrid Methods, part 1.” (1993).

Puckett, Elbridge Gerry, Ann S. Almgren, John B. Bell, Daniel L. Marcus, and William J. Rider. “A high-order projection method for tracking fluid interfaces in variable density incompressible flows.” Journal of Computational Physics130, no. 2 (1997): 269-282.

Boris, J. P., F. F. Grinstein, E. S. Oran, and R. L. Kolbe. “New insights into large eddy simulation.” Fluid dynamics research 10, no. 4-6 (1992): 199-228.

Porter, David H., Paul R. Woodward, and Annick Pouquet. “Inertial range structures in decaying compressible turbulent flows.” Physics of Fluids 10, no. 1 (1998): 237-245.

Margolin, Len G., and William J. Rider. “A rationale for implicit turbulence modelling.” International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 39, no. 9 (2002): 821-841.

Grinstein, Fernando F., Len G. Margolin, and William J. Rider, eds. Implicit large eddy simulation: computing turbulent fluid dynamics. Cambridge university press, 2007.

Fefferman, Charles L. “Existence and smoothness of the Navier-Stokes equation.” The millennium prize problems (2006): 57-67.

The largest portion and most important part of this process is the analysis that allows us to answer the question. Often the question needs to be broken down into a series of simpler questions some of which are amenable to easier solution. This process is hierarchical and cyclical. Sometimes the process forces us to step back and requires us to ask an even better or more proper question. In sense this is the process working in full with the better and more proper question being an act of creation and understanding. The analysis requires deep work and often study, research and educating oneself. A new question will force one to take the knowledge one has and combine it with new techniques producing enhanced capabilities. This process is on the job education, and fuels personal growth and personal growth fuels excellence. When you are answering a completely new question, you are doing research and helping to push the frontiers of science forward. When you are answering an old question, you are learning and you might answer the question in a new way yielding new understanding. At worst, you are growing as a person and professional.

The largest portion and most important part of this process is the analysis that allows us to answer the question. Often the question needs to be broken down into a series of simpler questions some of which are amenable to easier solution. This process is hierarchical and cyclical. Sometimes the process forces us to step back and requires us to ask an even better or more proper question. In sense this is the process working in full with the better and more proper question being an act of creation and understanding. The analysis requires deep work and often study, research and educating oneself. A new question will force one to take the knowledge one has and combine it with new techniques producing enhanced capabilities. This process is on the job education, and fuels personal growth and personal growth fuels excellence. When you are answering a completely new question, you are doing research and helping to push the frontiers of science forward. When you are answering an old question, you are learning and you might answer the question in a new way yielding new understanding. At worst, you are growing as a person and professional. Once this creation is available, new questions can be posed and solved. These creations allow new questions to be asked answered. This is the way of progress where technology and knowledge builds the bridge something better. If we support excellence and a process like this, we will progress. Without support for this process, we simply stagnate and whither away. The choice is simple either embrace excellence by loosening control, or chain people to mediocrity.

Once this creation is available, new questions can be posed and solved. These creations allow new questions to be asked answered. This is the way of progress where technology and knowledge builds the bridge something better. If we support excellence and a process like this, we will progress. Without support for this process, we simply stagnate and whither away. The choice is simple either embrace excellence by loosening control, or chain people to mediocrity. exact solution. This makes it a more difficult task than code verification where an exact solution is known removing a major uncertainty. A secondary issue associated with not knowing the exact solution is the implications on the nature of the solution itself. With an exact solution, a mathematical structure exists allowing the solution to be achievable analytically. Furthermore, exact solutions are limited to relatively simple models that often cannot model reality. Thus, the modeling approach to which solution verification is applied is necessarily more complex. All of these factors are confounding and produce a more perilous environment to conduct verification. The key product of solution verification is an estimate of numerical error and the secondary product is the rate of convergence. Both of these quantities are important to consider in the analysis.

exact solution. This makes it a more difficult task than code verification where an exact solution is known removing a major uncertainty. A secondary issue associated with not knowing the exact solution is the implications on the nature of the solution itself. With an exact solution, a mathematical structure exists allowing the solution to be achievable analytically. Furthermore, exact solutions are limited to relatively simple models that often cannot model reality. Thus, the modeling approach to which solution verification is applied is necessarily more complex. All of these factors are confounding and produce a more perilous environment to conduct verification. The key product of solution verification is an estimate of numerical error and the secondary product is the rate of convergence. Both of these quantities are important to consider in the analysis.

three unknowns,

three unknowns,  There are several practical issues related to this whole thread of discussion. One often encountered and extremely problematic issue is insanely high convergence rates. After one has been doing verification or seeing others do verification for a while, the analysis will sometimes provide an extremely high convergence rate. For example a second order method used to solve a problem will produce a sequence that produces a seeming 15th order solution (this example is given later). This is a ridiculous and results in woeful estimates of numerical error. A result like this usually indicates a solution on a tremendously unresolved mesh, and a generally unreliable simulation. This is one of those things that analysts should be mindful of. Constrained solution of the nonlinear equations can mitigate this possibility and exclude it a priori. This general approach including the solution with other norms, constraints and other aspects is explored in the paper on Robust Verification. The key concept is the solution to the error estimation problem is not unique and highly dependent upon assumptions. Different assumptions lead to different results to the problem and can be harnessed to make the analysis more robust and impervious to issues that might derail it.

There are several practical issues related to this whole thread of discussion. One often encountered and extremely problematic issue is insanely high convergence rates. After one has been doing verification or seeing others do verification for a while, the analysis will sometimes provide an extremely high convergence rate. For example a second order method used to solve a problem will produce a sequence that produces a seeming 15th order solution (this example is given later). This is a ridiculous and results in woeful estimates of numerical error. A result like this usually indicates a solution on a tremendously unresolved mesh, and a generally unreliable simulation. This is one of those things that analysts should be mindful of. Constrained solution of the nonlinear equations can mitigate this possibility and exclude it a priori. This general approach including the solution with other norms, constraints and other aspects is explored in the paper on Robust Verification. The key concept is the solution to the error estimation problem is not unique and highly dependent upon assumptions. Different assumptions lead to different results to the problem and can be harnessed to make the analysis more robust and impervious to issues that might derail it. Before moving to examples of solution verification we will show how robust verification can be used for code verification work. Since the error is known, the only uncertainty in the analysis is the rate of convergence. As we can immediately notice that this technique will get rid of a crucial ambiguity in the analysis. In standard code verification analysis, the rate of convergence is never the exact formal order, and expert judgment is used to determine if the results is close enough. With robust verification, the convergence rate has an uncertainty and the question of whether the exact value is included in the uncertainty band can be asked. Before showing the results for this application of robust verification, we need to note that the exact rate of verification is only the asymptotic rate in the limit of

Before moving to examples of solution verification we will show how robust verification can be used for code verification work. Since the error is known, the only uncertainty in the analysis is the rate of convergence. As we can immediately notice that this technique will get rid of a crucial ambiguity in the analysis. In standard code verification analysis, the rate of convergence is never the exact formal order, and expert judgment is used to determine if the results is close enough. With robust verification, the convergence rate has an uncertainty and the question of whether the exact value is included in the uncertainty band can be asked. Before showing the results for this application of robust verification, we need to note that the exact rate of verification is only the asymptotic rate in the limit of  s study using some initial grids that were known to be inadequate. One of the codes was relatively well trusted for this class of applications and produced three solutions that for all appearances appeared reasonable. One of the key parameters is the pressure drop through the test section. Using grids 664K, 1224K and 1934K elements we got pressure drops of 31.8 kPa, 24.6 kPa and 24.4 kPa respectively. Using a standard curve fitting for the effective mesh resolution gave an estimate of 24.3 kPa±0.0080 kPa for the resolved pressure drop and a convergence rate of 15.84. This is an absurd result and needs to simply be rejected immediately. Using the robust verification methodology on the same data set, gives a pressure drop of 16.1 kPa±13.5 kPa with a convergence rate of 1.23, which is reasonable. Subsequent calculations on refined grids produced results that were remarkably close to this estimate confirming the power of the technique even when given data that was substantially corrupted.

s study using some initial grids that were known to be inadequate. One of the codes was relatively well trusted for this class of applications and produced three solutions that for all appearances appeared reasonable. One of the key parameters is the pressure drop through the test section. Using grids 664K, 1224K and 1934K elements we got pressure drops of 31.8 kPa, 24.6 kPa and 24.4 kPa respectively. Using a standard curve fitting for the effective mesh resolution gave an estimate of 24.3 kPa±0.0080 kPa for the resolved pressure drop and a convergence rate of 15.84. This is an absurd result and needs to simply be rejected immediately. Using the robust verification methodology on the same data set, gives a pressure drop of 16.1 kPa±13.5 kPa with a convergence rate of 1.23, which is reasonable. Subsequent calculations on refined grids produced results that were remarkably close to this estimate confirming the power of the technique even when given data that was substantially corrupted. Our final example is a simple case of validation using the classical phenomena of vortex shedding over a cylinder at a relatively small Reynolds number. This is part of a reasonable effort to validate a research code before using in on more serious problems. The key experimental value to examine is the Stouhal number defined,

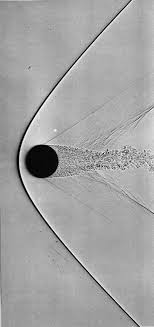

Our final example is a simple case of validation using the classical phenomena of vortex shedding over a cylinder at a relatively small Reynolds number. This is part of a reasonable effort to validate a research code before using in on more serious problems. The key experimental value to examine is the Stouhal number defined,

using a single discretization parameter only two discretizations are needed for verification (two equations to solve for two unknowns). For code verification the model for error is simple, generally a power law,

using a single discretization parameter only two discretizations are needed for verification (two equations to solve for two unknowns). For code verification the model for error is simple, generally a power law,  of accumulated error (since I’m using Mathematica so aspects of round-off error are pushed aside). In these cases round-off error would be another complication. Furthermore the backward Euler method for multiple equations would involve a linear (or nonlinear) solution that itself has an error tolerance that may significantly impact verification results. We see good results for

of accumulated error (since I’m using Mathematica so aspects of round-off error are pushed aside). In these cases round-off error would be another complication. Furthermore the backward Euler method for multiple equations would involve a linear (or nonlinear) solution that itself has an error tolerance that may significantly impact verification results. We see good results for  the quality of the solution that can be obtained. These two concepts go hand-in-hand. As simple closed form solution is easy to obtain and evaluation. Conversely, a numerical solution of partial differential equations is difficult and carries a number of serious issues regarding its quality and trustworthiness. These issues are addressed by an increased level of scrutiny on evidence provided by associated data. Each of benchmark is not necessarily analytical in nature, and the solutions are each constructed in different means with different expected levels of quality and accompanying data. This necessitates the differences in level of required documentation and accompanying supporting material to assure the user of its quality.

the quality of the solution that can be obtained. These two concepts go hand-in-hand. As simple closed form solution is easy to obtain and evaluation. Conversely, a numerical solution of partial differential equations is difficult and carries a number of serious issues regarding its quality and trustworthiness. These issues are addressed by an increased level of scrutiny on evidence provided by associated data. Each of benchmark is not necessarily analytical in nature, and the solutions are each constructed in different means with different expected levels of quality and accompanying data. This necessitates the differences in level of required documentation and accompanying supporting material to assure the user of its quality. The use of DNS as a surrogate for experimental data has received significant attention. This practice violates the fundamental definition of validation we have adopted because no observation of the physical world is used to define the data. This practice also raises other difficulties, which we will elaborate upon. First the DNS code itself requires that the verification basis further augmented by a validation basis for its application. This includes all the activities that would define a validation study including experimental uncertainty analysis numerical and physical equation based error analysis. Most commonly, the DNS serves to provide validation, but the DNS contains approximation errors that must be estimated as part of the “error bars” for the data. Furthermore, the code must have documented credibility beyond the details of the calculation used as data. This level of documentation again takes the form of the last form of verification benchmark introduced above because of the nature of DNS codes. For this reason we include DNS as a member of this family of benchmarks.

The use of DNS as a surrogate for experimental data has received significant attention. This practice violates the fundamental definition of validation we have adopted because no observation of the physical world is used to define the data. This practice also raises other difficulties, which we will elaborate upon. First the DNS code itself requires that the verification basis further augmented by a validation basis for its application. This includes all the activities that would define a validation study including experimental uncertainty analysis numerical and physical equation based error analysis. Most commonly, the DNS serves to provide validation, but the DNS contains approximation errors that must be estimated as part of the “error bars” for the data. Furthermore, the code must have documented credibility beyond the details of the calculation used as data. This level of documentation again takes the form of the last form of verification benchmark introduced above because of the nature of DNS codes. For this reason we include DNS as a member of this family of benchmarks.

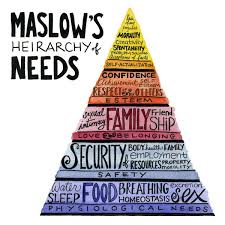

achieve a degree of access to resources that raise their access to a good life. With more resources the citizens can aspire toward a better, easier more fulfilled life. In essence the security of a Nation can allow people to exist higher on Maslow’s hierarchy needs. In the United States this is commonly expressed as “freedom”. Freedom is a rather superficial thing when used as a slogan. The needs of the citizens begin with having food and shelter than allow them to aspire toward a sense of personal safety. Societal safety is one means of achieving this (not that safety and security are pretty low on the hierarchy). With these in hand, the sense of community can be pursued and then sense of an esteemed self. Finally we get to the peak and the ability to pursue ones full personal potential.

achieve a degree of access to resources that raise their access to a good life. With more resources the citizens can aspire toward a better, easier more fulfilled life. In essence the security of a Nation can allow people to exist higher on Maslow’s hierarchy needs. In the United States this is commonly expressed as “freedom”. Freedom is a rather superficial thing when used as a slogan. The needs of the citizens begin with having food and shelter than allow them to aspire toward a sense of personal safety. Societal safety is one means of achieving this (not that safety and security are pretty low on the hierarchy). With these in hand, the sense of community can be pursued and then sense of an esteemed self. Finally we get to the peak and the ability to pursue ones full personal potential. . If one exists at this level, life isn’t very good, but its achievement is necessary for a better life. Gradually one moves up the hierarchy requiring greater access to resources and ease of maintaining the lower positions on the hierarchy. A vibrant National Security should allow this to happen, the richer a Nation becomes the higher on the hierarchy of needs its citizens reside. It is with some recognition of irony that my efforts and the Nation is stuck at such a low level on the hierarchy. Efforts toward bolstering the community the Nation forms seem to be too difficult to achieve today. We seem to be regressing from being a community or achieving personal fulfillment. We are stuck trying to be safe and secure. The question is whether those in the Nation can effectively provide the basis for existing high on the hierarchy of needs without being there themselves?

. If one exists at this level, life isn’t very good, but its achievement is necessary for a better life. Gradually one moves up the hierarchy requiring greater access to resources and ease of maintaining the lower positions on the hierarchy. A vibrant National Security should allow this to happen, the richer a Nation becomes the higher on the hierarchy of needs its citizens reside. It is with some recognition of irony that my efforts and the Nation is stuck at such a low level on the hierarchy. Efforts toward bolstering the community the Nation forms seem to be too difficult to achieve today. We seem to be regressing from being a community or achieving personal fulfillment. We are stuck trying to be safe and secure. The question is whether those in the Nation can effectively provide the basis for existing high on the hierarchy of needs without being there themselves? opportune time. Moore’s law is dead, and may be dead at all scales of computation. It may be the highest hanging fruit pursued at great cost while lower hanging fruits rots away without serious attention, or even conscious neglect. Perhaps nothing typifies this issue more than the state of validation in modeling and simulation.

opportune time. Moore’s law is dead, and may be dead at all scales of computation. It may be the highest hanging fruit pursued at great cost while lower hanging fruits rots away without serious attention, or even conscious neglect. Perhaps nothing typifies this issue more than the state of validation in modeling and simulation.

“What is a model?”

“What is a model?”  To conduct a validation assessment you need observations to compare to. This is an absolute necessity; if you have no observational data, you have no validation. Once the data is at hand, you need to understand how good it is. This means understanding how uncertain the data is. This uncertainty can come from three major aspects of the process: errors in measurement, errors in statistics, and errors in interpretation. In the order of how these were mentioned each of these categories become more difficult to assess and less common to actually be assessed in practice. Most commonly assessed is measurement error that is the uncertainty of the value of a measured quantity. This is a function of the measurement technology or the inference of the quantity from other data. The second aspect is associated with the statistical nature of the measurement. Is the observation or experiment repeatable? If it is not how much might the measured value differ due to changes in the system being observed? How typical are the measured values? In many cases this issue is ignored in a willfully ignorant manner. Finally, the hardest part of observational bias often defined as answering the question, “how do we know that we a measuring what we think we are?” Is there something systematic in our observed system that we have not accounted for that might be changing our observations. This may come from some sort of problem in calibrating measurements, or looking at the observed system in a manner that is inconsistent. These all lead to potential bias and distortion of the measurements.

To conduct a validation assessment you need observations to compare to. This is an absolute necessity; if you have no observational data, you have no validation. Once the data is at hand, you need to understand how good it is. This means understanding how uncertain the data is. This uncertainty can come from three major aspects of the process: errors in measurement, errors in statistics, and errors in interpretation. In the order of how these were mentioned each of these categories become more difficult to assess and less common to actually be assessed in practice. Most commonly assessed is measurement error that is the uncertainty of the value of a measured quantity. This is a function of the measurement technology or the inference of the quantity from other data. The second aspect is associated with the statistical nature of the measurement. Is the observation or experiment repeatable? If it is not how much might the measured value differ due to changes in the system being observed? How typical are the measured values? In many cases this issue is ignored in a willfully ignorant manner. Finally, the hardest part of observational bias often defined as answering the question, “how do we know that we a measuring what we think we are?” Is there something systematic in our observed system that we have not accounted for that might be changing our observations. This may come from some sort of problem in calibrating measurements, or looking at the observed system in a manner that is inconsistent. These all lead to potential bias and distortion of the measurements. The intrinsic benefit of this approach is a systematic investigation of the ability of the model to produce the features of reality. Ultimately the model needs to produce the features of reality that we care about, and can measure. This combination is good to balance in the process of validation, the ability to produce the reality necessary to conduct engineering and science, but also general observations. A really good confidence builder is the ability of model to produce proper results on things that we care as well as those don’t care about. One of the core issues is the high probability that many of the things we care about in a model cannot be observed, and the model acts as an inference device for science. In this case the observations act to provide confidence that the model’s inferences can be trusted. One of the keys to the whole enterprise is understanding the uncertainty intrinsic to these inferences, and good validation provides essential information for this.

The intrinsic benefit of this approach is a systematic investigation of the ability of the model to produce the features of reality. Ultimately the model needs to produce the features of reality that we care about, and can measure. This combination is good to balance in the process of validation, the ability to produce the reality necessary to conduct engineering and science, but also general observations. A really good confidence builder is the ability of model to produce proper results on things that we care as well as those don’t care about. One of the core issues is the high probability that many of the things we care about in a model cannot be observed, and the model acts as an inference device for science. In this case the observations act to provide confidence that the model’s inferences can be trusted. One of the keys to the whole enterprise is understanding the uncertainty intrinsic to these inferences, and good validation provides essential information for this. One of the greatest issues in validation is “negligible” errors and uncertainties. In many cases these errors are negligible by assertion and no evidence is given. A standing suggestion is that any negligible error or uncertainty be given a numerical value along with evidence for that value. If this cannot be done, the assertion is most likely to be specious, or at least poorly thought through. If you know it is small then you should know how small and why. It is more likely is that it is based on some combination of laziness and wishful thinking. In other cases this practice is an act of negligence, and worse yet it is simply willful ignorance on the part of practitioners. This is an equal opportunity issue for computational modeling and experiments. Often (almost always!) numerical errors are completely ignored in validation. The most brazen violators will simply assert without evidence that the errors are small or the calculated is converged without offering any evidence beyond authority.

One of the greatest issues in validation is “negligible” errors and uncertainties. In many cases these errors are negligible by assertion and no evidence is given. A standing suggestion is that any negligible error or uncertainty be given a numerical value along with evidence for that value. If this cannot be done, the assertion is most likely to be specious, or at least poorly thought through. If you know it is small then you should know how small and why. It is more likely is that it is based on some combination of laziness and wishful thinking. In other cases this practice is an act of negligence, and worse yet it is simply willful ignorance on the part of practitioners. This is an equal opportunity issue for computational modeling and experiments. Often (almost always!) numerical errors are completely ignored in validation. The most brazen violators will simply assert without evidence that the errors are small or the calculated is converged without offering any evidence beyond authority. tempt at perfection.

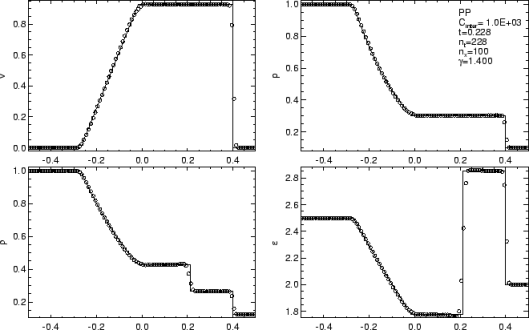

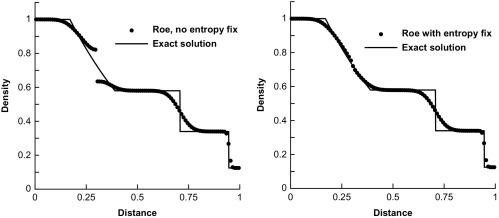

tempt at perfection. For gas dynamics, the mathematics of the model provide us with some very general character to the problems we solve. Shock waves are the preeminent feature of compressible gas dynamics, and a relatively predominant focal point for methods’ development and developer attention. Shock waves are nonlinear and naturally steepen thus countering dissipative effects. Shocks benefit through their character as garbage collectors, they are dissipative features and as a result destroy information. Some of this destruction limits the damage done by poor choices of numerical treatment. Being nonlinear one has to be careful with shocks. The very worst thing you can do is to add too little dissipation because this will allow the solution to generate unphysical noise or oscillations that are emitted by the shock. These oscillations will then become features of the solution. A lot of the robustness we seek comes from not producing oscillations, which can be best achieved with generous dissipation at shocks. Shocks receive so much attention because their improper treatment is utterly catastrophic, but they are not the only issue; the others are just more subtle and less apparently deadly.

For gas dynamics, the mathematics of the model provide us with some very general character to the problems we solve. Shock waves are the preeminent feature of compressible gas dynamics, and a relatively predominant focal point for methods’ development and developer attention. Shock waves are nonlinear and naturally steepen thus countering dissipative effects. Shocks benefit through their character as garbage collectors, they are dissipative features and as a result destroy information. Some of this destruction limits the damage done by poor choices of numerical treatment. Being nonlinear one has to be careful with shocks. The very worst thing you can do is to add too little dissipation because this will allow the solution to generate unphysical noise or oscillations that are emitted by the shock. These oscillations will then become features of the solution. A lot of the robustness we seek comes from not producing oscillations, which can be best achieved with generous dissipation at shocks. Shocks receive so much attention because their improper treatment is utterly catastrophic, but they are not the only issue; the others are just more subtle and less apparently deadly. The fourth standard feature is shear waves, which are a different form of linearly degenerate waves. Shear waves are heavily related to turbulence, thus being a huge source of terror. In one dimension shear is rather innocuous being just another contact, but in two or three dimensions our current knowledge and technical capabilities are quickly overwhelmed. Once you have a turbulent flow, one must deal with the conflation of numerical error, and modeling becomes a pernicious aspect of a calculation. In multiple dimensions the shear is almost invariably unstable and solutions become chaotic and boundless in terms of complexity. This boundless complexity means that solutions are significantly mesh dependent, and demonstrably non-convergent in a point wise sense. There may be a convergence in a measure-valued sense, but these concepts are far from well defined, fully explored and technically agreed upon.

The fourth standard feature is shear waves, which are a different form of linearly degenerate waves. Shear waves are heavily related to turbulence, thus being a huge source of terror. In one dimension shear is rather innocuous being just another contact, but in two or three dimensions our current knowledge and technical capabilities are quickly overwhelmed. Once you have a turbulent flow, one must deal with the conflation of numerical error, and modeling becomes a pernicious aspect of a calculation. In multiple dimensions the shear is almost invariably unstable and solutions become chaotic and boundless in terms of complexity. This boundless complexity means that solutions are significantly mesh dependent, and demonstrably non-convergent in a point wise sense. There may be a convergence in a measure-valued sense, but these concepts are far from well defined, fully explored and technically agreed upon. ns. The usual aim of solvers is to completely remove dissipation, but that runs the risk of violating the second law. It may be more advisable to keep a small positive dissipation working (perhaps using a hyperviscosity partially because control volumes add a nonlinear anti-dissipative error). This way the code stays away from circumstances that violate this essential physical law. We can work with other forms of entropy satisfaction too. Most notably is Lax’s condition that identifies the structures in a flow by the local behavior of the relevant characteristics of the flow. Across a shock the characteristics flow into the shock, and this condition should be met with dissipation. These structures are commonly present in the head of rarefactions.

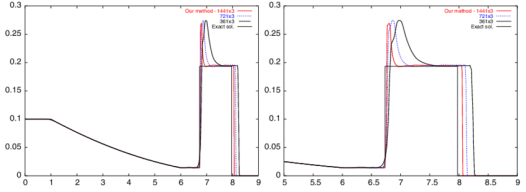

ns. The usual aim of solvers is to completely remove dissipation, but that runs the risk of violating the second law. It may be more advisable to keep a small positive dissipation working (perhaps using a hyperviscosity partially because control volumes add a nonlinear anti-dissipative error). This way the code stays away from circumstances that violate this essential physical law. We can work with other forms of entropy satisfaction too. Most notably is Lax’s condition that identifies the structures in a flow by the local behavior of the relevant characteristics of the flow. Across a shock the characteristics flow into the shock, and this condition should be met with dissipation. These structures are commonly present in the head of rarefactions. hods I have devised or the MP methods of Suresh and Huynh. Both of these methods are significantly more accurate than WENO methods.

hods I have devised or the MP methods of Suresh and Huynh. Both of these methods are significantly more accurate than WENO methods. technology and communication unthinkable a generation before. My chosen profession looks increasingly like a relic of that Cold War, and increasingly irrelevant to the World that unfolds before me. My workplace is failing to keep pace with change, and I’m seeing it fall behind modernity in almost every respect. It’s a safe, secure job, but lacks most of the edge the real World offers. All of the forces unleashed in today’s World make for incredible excitement, possibility, incredible terror and discomfort. The potential for humanity is phenomenal, and the risks are profound. In short, we live in simultaneously in incredibly exciting and massively sucky times. Yes, both of these seemingly conflicting things can be true.

technology and communication unthinkable a generation before. My chosen profession looks increasingly like a relic of that Cold War, and increasingly irrelevant to the World that unfolds before me. My workplace is failing to keep pace with change, and I’m seeing it fall behind modernity in almost every respect. It’s a safe, secure job, but lacks most of the edge the real World offers. All of the forces unleashed in today’s World make for incredible excitement, possibility, incredible terror and discomfort. The potential for humanity is phenomenal, and the risks are profound. In short, we live in simultaneously in incredibly exciting and massively sucky times. Yes, both of these seemingly conflicting things can be true. violence increasingly in a state-sponsored way is increasing. The violence against change is growing whether it is by governments or terrorists. What isn’t commonly appreciated is the alliance in violence of the right wing and terrorists. Both are fighting against the sorts of changes modernity is bringing. The fight against terror is giving the violent right wing more power. The right wing and Islamic terrorists have the same aim, undoing the push toward progress with modern views of race, religion and morality. The only difference is the name of the prophet the violence is done in name of.

violence increasingly in a state-sponsored way is increasing. The violence against change is growing whether it is by governments or terrorists. What isn’t commonly appreciated is the alliance in violence of the right wing and terrorists. Both are fighting against the sorts of changes modernity is bringing. The fight against terror is giving the violent right wing more power. The right wing and Islamic terrorists have the same aim, undoing the push toward progress with modern views of race, religion and morality. The only difference is the name of the prophet the violence is done in name of. which provides the rich and powerful the tools to control their societies as well. They also wage war against the sources of terrorism creating the conditions and recruiting for more terrorists. The police states have reduced freedom and lots of censorship, imprisonment, and opposition to personal empowerment. The same police states are effective at repressing minority groups within nations using the weapons gained to fight terror. Together these all help the cause of the right wing in blunting progress. The two allies like to kill each other too, but the forces of hate; fear and doubt work to their greater ends. In fighting terrorism we are giving them exactly what they want, the reduction of our freedom and progress. This is also the aim of right wing; stop the frightening future from arriving through the imposition of traditional values. This is exactly what the religious extremists want be they Islamic or Christian.

which provides the rich and powerful the tools to control their societies as well. They also wage war against the sources of terrorism creating the conditions and recruiting for more terrorists. The police states have reduced freedom and lots of censorship, imprisonment, and opposition to personal empowerment. The same police states are effective at repressing minority groups within nations using the weapons gained to fight terror. Together these all help the cause of the right wing in blunting progress. The two allies like to kill each other too, but the forces of hate; fear and doubt work to their greater ends. In fighting terrorism we are giving them exactly what they want, the reduction of our freedom and progress. This is also the aim of right wing; stop the frightening future from arriving through the imposition of traditional values. This is exactly what the religious extremists want be they Islamic or Christian. Driving the conservatives to such heights of violence and fear are changes to society of massive scale. Demographics are driving the changes with people of color becoming impossible to ignore, along with an aging population. Sexual freedom has emboldened people to break free of traditional boundaries of behavior, gender and relationships. Technology is accelerating the change and empowering people in amazing ways. All of this terrifies many people and provides extremists with the sort of alarmist rhetoric needed to grab power. We see these forces rushing headlong toward each other with society-wide conflict the impact. Progressive and conservative blocks are headed toward a massive fight. This also lines up along urban and rural lines, young and old, educated and uneducated. The future hangs in the balance and it is not clear who has the advantage.

Driving the conservatives to such heights of violence and fear are changes to society of massive scale. Demographics are driving the changes with people of color becoming impossible to ignore, along with an aging population. Sexual freedom has emboldened people to break free of traditional boundaries of behavior, gender and relationships. Technology is accelerating the change and empowering people in amazing ways. All of this terrifies many people and provides extremists with the sort of alarmist rhetoric needed to grab power. We see these forces rushing headlong toward each other with society-wide conflict the impact. Progressive and conservative blocks are headed toward a massive fight. This also lines up along urban and rural lines, young and old, educated and uneducated. The future hangs in the balance and it is not clear who has the advantage. maintain communication via text, audio or video with amazing ease. This starts to form different communities and relationships that are shaking culture. It’s mostly a middle class phenomenon and thus the poor are left out, and afraid.

maintain communication via text, audio or video with amazing ease. This starts to form different communities and relationships that are shaking culture. It’s mostly a middle class phenomenon and thus the poor are left out, and afraid. For example in my public life, I am not willing to give up the progress, and feel that the right wing is agitating to push the clock back. The right wing feels the changes are immoral and frightening and want to take freedom away. They will do it in the name of fighting terrorism while clutching the mantle of white nationalism and the Bible in the other hand. Similar mixes are present in Europe, Russia, and remarkably across the Arab world. My work World is increasingly allied with the forces against progress. I see a deep break in the not to distant future where the progress scientific research depends upon will be utterly incongruent with the values of my security-obsessed work place. The two things cannot live together effectively and ultimately the work will be undone by its inability to commit itself to being part of the modern World. The forces of progress are powerful and seemingly unstoppable too. We are seeing the unstoppable force of progress meet the immovable object of fear and oppression. It is going to be violent and sudden. My belief in progress is steadfast, and unwavering. Nonetheless, we have had episodes in human history where progress was stopped. Anyone heard of the dark ages? It can happen.

For example in my public life, I am not willing to give up the progress, and feel that the right wing is agitating to push the clock back. The right wing feels the changes are immoral and frightening and want to take freedom away. They will do it in the name of fighting terrorism while clutching the mantle of white nationalism and the Bible in the other hand. Similar mixes are present in Europe, Russia, and remarkably across the Arab world. My work World is increasingly allied with the forces against progress. I see a deep break in the not to distant future where the progress scientific research depends upon will be utterly incongruent with the values of my security-obsessed work place. The two things cannot live together effectively and ultimately the work will be undone by its inability to commit itself to being part of the modern World. The forces of progress are powerful and seemingly unstoppable too. We are seeing the unstoppable force of progress meet the immovable object of fear and oppression. It is going to be violent and sudden. My belief in progress is steadfast, and unwavering. Nonetheless, we have had episodes in human history where progress was stopped. Anyone heard of the dark ages? It can happen. work. This is delivered with disempowering edicts and policies that conspire to shackle me, and keep me from doing anything. The real message is that nothing you do is important enough to risk fucking up. I’m convinced that the things making work suck are strongly connected to everything else.

work. This is delivered with disempowering edicts and policies that conspire to shackle me, and keep me from doing anything. The real message is that nothing you do is important enough to risk fucking up. I’m convinced that the things making work suck are strongly connected to everything else. adapting and pushing themselves forward, the organization will stagnate or be left behind by the exciting innovations shaping the World today. When the motivation of the organization fails to emphasize productivity and efficiency, the recipe is disastrous. Modern technology offers the potential for incredible advances, but only if they’re seeking advantage. If minds are not open to making things better, it is a recipe for frustration.

adapting and pushing themselves forward, the organization will stagnate or be left behind by the exciting innovations shaping the World today. When the motivation of the organization fails to emphasize productivity and efficiency, the recipe is disastrous. Modern technology offers the potential for incredible advances, but only if they’re seeking advantage. If minds are not open to making things better, it is a recipe for frustration. unwittingly enter into the opposition to change, and assist the conservative attempt to hold onto the past.

unwittingly enter into the opposition to change, and assist the conservative attempt to hold onto the past. code. You found some really good problems that “go to eleven.” If you do things right, your code will eventually “break” in some way. The closer you look, the more likely it’ll be broken. Heck your code is probably already broken, and you just don’t know it! Once it’s broken, what should you do? How do you get the code back into working order? What can you do to figure out why it’s broken? How do you live with the knowledge of the limitations of the code? Those limitations are there, but usually you don’t know them very well. Essentially you’ve gone about the process of turning over rocks with your code until you find something awfully dirty-creepy crawly underneath. You then have mystery to solve, and/or ambiguity to live with from the results.

code. You found some really good problems that “go to eleven.” If you do things right, your code will eventually “break” in some way. The closer you look, the more likely it’ll be broken. Heck your code is probably already broken, and you just don’t know it! Once it’s broken, what should you do? How do you get the code back into working order? What can you do to figure out why it’s broken? How do you live with the knowledge of the limitations of the code? Those limitations are there, but usually you don’t know them very well. Essentially you’ve gone about the process of turning over rocks with your code until you find something awfully dirty-creepy crawly underneath. You then have mystery to solve, and/or ambiguity to live with from the results.

failures that can go unnoticed without expert attention. One of the key things is the loss of accuracy in a solution. This could be the numerical level of error being wrong, or the rate of convergence of the solution being outside the theoretical guarantees for the method (convergence rates are a function of the method and the nature of the solution itself). Sometimes this character is associated with an overly dissipative solution where numerical dissipation is too large to be tolerated. At this subtle level we are judging failure by a high standard based on knowledge and expectations driven by deep theoretical understanding. These failings generally indicate you are at a good level of testing and quality.

failures that can go unnoticed without expert attention. One of the key things is the loss of accuracy in a solution. This could be the numerical level of error being wrong, or the rate of convergence of the solution being outside the theoretical guarantees for the method (convergence rates are a function of the method and the nature of the solution itself). Sometimes this character is associated with an overly dissipative solution where numerical dissipation is too large to be tolerated. At this subtle level we are judging failure by a high standard based on knowledge and expectations driven by deep theoretical understanding. These failings generally indicate you are at a good level of testing and quality. methods. You should be intimately familiar with the conditions for stability for the code’s methods. You should assure that the stability conditions are not being exceeded. If a stability condition is missed, or calculated incorrectly, the impact is usually immediate and catastrophic. One way to do this on the cheap is modify the code’s stability condition to a more conservative version usually with a smaller safety factor. If the catastrophic behavior goes away then it points a finger at the stability condition with some certainty. Either the method is wrong, or not coded correctly, or you don’t really understand the stability condition properly. It is important to figure out which of these possibilities you’re subject to. Sometimes this needs to be studied using analytical techniques to examine the stability theoretically.

methods. You should be intimately familiar with the conditions for stability for the code’s methods. You should assure that the stability conditions are not being exceeded. If a stability condition is missed, or calculated incorrectly, the impact is usually immediate and catastrophic. One way to do this on the cheap is modify the code’s stability condition to a more conservative version usually with a smaller safety factor. If the catastrophic behavior goes away then it points a finger at the stability condition with some certainty. Either the method is wrong, or not coded correctly, or you don’t really understand the stability condition properly. It is important to figure out which of these possibilities you’re subject to. Sometimes this needs to be studied using analytical techniques to examine the stability theoretically. Another approach to take is systematically make the problem you’re solving easier until the results are “correct,” or the catastrophic behavior is replaced with something less odious. An important part of this process is more deeply understand how the problems are being triggered in the code. What sort of condition is being exceeded and how are the methods in the code going south? Is there something explicit that can be done to change the methodology so that this doesn’t happen? Ultimately, the issue is a systematic understanding of how the code and its method’s behave, their strengths and weaknesses. Once the weakness is exposed in the testing can you do something to get rid of it? Whether the weakness is a bug or feature of the code is another question to answer. Through the process of successively harder problems one can make the code better and better until you’re at the limits of knowledge.

Another approach to take is systematically make the problem you’re solving easier until the results are “correct,” or the catastrophic behavior is replaced with something less odious. An important part of this process is more deeply understand how the problems are being triggered in the code. What sort of condition is being exceeded and how are the methods in the code going south? Is there something explicit that can be done to change the methodology so that this doesn’t happen? Ultimately, the issue is a systematic understanding of how the code and its method’s behave, their strengths and weaknesses. Once the weakness is exposed in the testing can you do something to get rid of it? Whether the weakness is a bug or feature of the code is another question to answer. Through the process of successively harder problems one can make the code better and better until you’re at the limits of knowledge. Whether you are at the limits of knowledge takes a good deal of experience and study. You need to know the field and your competition quite well. You need to be willing to borrow from others and consider their success carefully. There is little time for pride, if you want to get to the frontier of capability; you need to be brutal and focused along the path. You need to keep pushing your code with harder testing and not be satisfied with the quality. Eventually you will get to problems that cannot be overcome with what people know how to do. At that point your methodology probably needs to evolve a bit. This is really hard work, and prone to risk and failure. For this reason most codes never get to this level of endeavor, its simply too hard on the code developers, and worse on those managing them. Today’s management of science simply doesn’t enable the level of risk and failure necessary to get to the summit of our knowledge. Management wants sure results and cannot deal with ambiguity at all, and striving at the frontier of knowledge is full of it, and usually ends up failing.