Linearity Breeds Contempt

—Peter Lax

A few weeks ago I went into my office and found a book waiting for me. It was one of the most pleasant surprises I’ve had at work for a long while, a biography of Peter Lax written by Reuben Hersh. Hersh is an emeritus professor of mathematics at the University of New Mexico (my alma mater), and a student of Lax at NYU. The book was a gift from my friend, Tim Trucano, who knew of my high regard and depth of appreciation for the work of Lax. I believe that Lax is one of the most important mathematicians of the 20th Century and he embodies a spirit that is all too lacking from current mathematical work. It is Lax’s steadfast commitment and execution of great pure math as a vehicle to producing great applied math that the book explicitly reports and implicitly advertises. Lax never saw a divide in math between the two and complete compatibility between them.

The publisher is the American Mathematical Society (AMS) and the book is a wonderfully technical and personal account of the fascinating and influential life of Peter Lax. Hersh’s account goes far beyond the obvious public and professional impact of Lax into his personal life and family although these are colored greatly by the greatest events of the 20th Century. Lax also has a deep connection to three themes in my own life: scientific computing, hyperbolic conservation laws and Los Alamos. He was a contributing member of the Manhattan Project despite being a corporal in the US Army and only 18 years old! Los Alamos and John von Neumann in particular had an immense influence on his life’s work with the fingerprints of that influence all over his greatest professional achievements.

The publisher is the American Mathematical Society (AMS) and the book is a wonderfully technical and personal account of the fascinating and influential life of Peter Lax. Hersh’s account goes far beyond the obvious public and professional impact of Lax into his personal life and family although these are colored greatly by the greatest events of the 20th Century. Lax also has a deep connection to three themes in my own life: scientific computing, hyperbolic conservation laws and Los Alamos. He was a contributing member of the Manhattan Project despite being a corporal in the US Army and only 18 years old! Los Alamos and John von Neumann in particular had an immense influence on his life’s work with the fingerprints of that influence all over his greatest professional achievements.

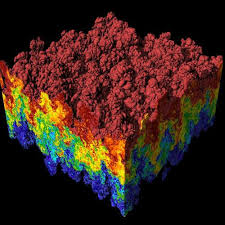

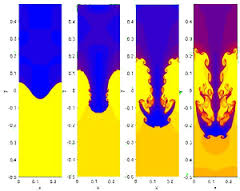

In 1945 scientific computing was just being born having provided an early example in a simulation of the plutonium bomb the previous year. Von Neumann was a visionary in scientific computing having already created the first shock capturing method and realizing the necessity of tackling the solution of shock waves through numerical investigations. The first real computers were a twinkle in Von Neumann’s eye. Lax was exposed to these ideas and along with his mentors at New York University (NYU), Courant and Friedrichs, soon set out making his own contributions to the field. It is easily defensible to credit Lax as being one of the primary creators of the field, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) along with Von Neumann and Frank Harlow. All of these men had a direct association with Los Alamos and access to computers, resources and applications that drove the creation of this area of study.

In 1945 scientific computing was just being born having provided an early example in a simulation of the plutonium bomb the previous year. Von Neumann was a visionary in scientific computing having already created the first shock capturing method and realizing the necessity of tackling the solution of shock waves through numerical investigations. The first real computers were a twinkle in Von Neumann’s eye. Lax was exposed to these ideas and along with his mentors at New York University (NYU), Courant and Friedrichs, soon set out making his own contributions to the field. It is easily defensible to credit Lax as being one of the primary creators of the field, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) along with Von Neumann and Frank Harlow. All of these men had a direct association with Los Alamos and access to computers, resources and applications that drove the creation of this area of study.

Lax’s work started with his thesis work at NYU, and continued with a year on staff at Los Alamos from 1949-1951. It is remarkable that upon leaving Los Alamos to take a professorship at NYU his vision of the future technical work in the area of shock waves and CFD had already achieved remarkable clarity of purpose and direction. He spent the next 20 years filling in all the details and laying the foundation for CFD for hyperbolic conservation laws across the world. He returned to Los Alamos every summer for a while and encouraged his students to do the same. He always felt that the applied environment should provide inspiration for mathematics and the problems studied by Los Alamos were weighty and important. Moreover he was a firm believer in the cause of the defense of the Country and its ideals. Surely this was a product of being driven from his native Hungary by the Nazis and their allies.

Lax’s work started with his thesis work at NYU, and continued with a year on staff at Los Alamos from 1949-1951. It is remarkable that upon leaving Los Alamos to take a professorship at NYU his vision of the future technical work in the area of shock waves and CFD had already achieved remarkable clarity of purpose and direction. He spent the next 20 years filling in all the details and laying the foundation for CFD for hyperbolic conservation laws across the world. He returned to Los Alamos every summer for a while and encouraged his students to do the same. He always felt that the applied environment should provide inspiration for mathematics and the problems studied by Los Alamos were weighty and important. Moreover he was a firm believer in the cause of the defense of the Country and its ideals. Surely this was a product of being driven from his native Hungary by the Nazis and their allies.

Lax also comes from a Hungarian heritage that provided some of the greatest minds of the 20th Century with Von N eumann and Teller being standouts. Their immense intellectual gifts were driven Westward to America through the incalculable hatred and violence of the Nazis and their allies in World War 2. Ultimately, the United States benefited by providing these refugees sanctuary against the forces of hate and intolerance. This among other things led to the Nazis defeat and should provide an ample lesson regarding the values of tolerance and openness as a contrast.

eumann and Teller being standouts. Their immense intellectual gifts were driven Westward to America through the incalculable hatred and violence of the Nazis and their allies in World War 2. Ultimately, the United States benefited by providing these refugees sanctuary against the forces of hate and intolerance. This among other things led to the Nazis defeat and should provide an ample lesson regarding the values of tolerance and openness as a contrast.

The book closes with an overview of Lax’s major areas of technical achievement in a series of short essays. Lax received the Abel Prize for Mathematics in 2005 because of the depth and breath of his work in these areas. While hyperbolic conservation laws and CFD were foremost in his resume, he produced great mathematics in a number of other areas. In addition he provided continuous service to the NYU and United States in broader scientific leadership positions.

Before laying out these topics the book makes a special effort to describe Lax’s devotion to the creation of mathematics that is both pure and applied. In other words beautiful mathematics that stands toe to toe with any other pure math, but also has application to problems in the real world. He has an unwavering commitment to the idea that applied math should be good pure math too. The two are not in any way incompatible. Today too many mathematicians are keen to dismiss applied math as being a lesser topic and beneath pure math as a discipline.

This attitude is harmful to all of mathematics and the root of many deep problems in the field today. Mathematicians far and wide would be well-served to look to Lax as a shining example of how they should be thinking, solve problems, be of service and contribute to a better World.

…who may regard using finite differences as the last resort of a scoundrel that the theory of difference equations is a rather sophisticated affair, more sophisticated than the corresponding theory of partial differential equations.

—Peter Lax

me ten years ago, I’d have thought aliens delivered the technology to humans.

me ten years ago, I’d have thought aliens delivered the technology to humans.

In a sense the modern trajectory of supercomputing is quintessentially American, bigger and faster is better by fiat. Excess and waste are virtues rather than flaw. Except the modern supercomputer it is not better, and not just because they don’t hold a candle to the old Crays. These computers just suck in so many ways; they are soulless and devoid of character. Moreover they are already a massive pain in the ass to use, and plans are afoot to make them even worse. The unrelenting priority of speed over utility is crushing. Terrible is the only path to speed, and terrible is coming with a tremendous cost too. When a colleague recently quipped that she would like to see us get a computer we actually wanted to use, I’m convinced that she had the older generation of Crays firmly in mind.

In a sense the modern trajectory of supercomputing is quintessentially American, bigger and faster is better by fiat. Excess and waste are virtues rather than flaw. Except the modern supercomputer it is not better, and not just because they don’t hold a candle to the old Crays. These computers just suck in so many ways; they are soulless and devoid of character. Moreover they are already a massive pain in the ass to use, and plans are afoot to make them even worse. The unrelenting priority of speed over utility is crushing. Terrible is the only path to speed, and terrible is coming with a tremendous cost too. When a colleague recently quipped that she would like to see us get a computer we actually wanted to use, I’m convinced that she had the older generation of Crays firmly in mind. We have to go back to the mid-1990’s and the combination of computing and geopolitical issues that existed then. The path taken by the classic Cray supercomputers appeared to be running out of steam insofar as improving performance. The attack of the killer micros was defined as the path to continued growth in performance. Overall hardware functionality was effectively abandoned in favor of pure performance. The pure performance was only achieved in the case of benchmark problems that had little in common with actual applications. Performance on real application took a nosedive; a nosedive that the benchmark conveniently covered up. We still haven’t woken up to the reality.

We have to go back to the mid-1990’s and the combination of computing and geopolitical issues that existed then. The path taken by the classic Cray supercomputers appeared to be running out of steam insofar as improving performance. The attack of the killer micros was defined as the path to continued growth in performance. Overall hardware functionality was effectively abandoned in favor of pure performance. The pure performance was only achieved in the case of benchmark problems that had little in common with actual applications. Performance on real application took a nosedive; a nosedive that the benchmark conveniently covered up. We still haven’t woken up to the reality.

are also prone to failures where ideas simply don’t pan out. Without the failure you don’t have the breakthroughs hence the fatal nature of risk aversion. Integrated over decades of timid low-risk behavior we have the makings of a crisis. Our low-risk behavior has already created a fast immeasurable gulf in what we can do today versus what we should be doing today.

are also prone to failures where ideas simply don’t pan out. Without the failure you don’t have the breakthroughs hence the fatal nature of risk aversion. Integrated over decades of timid low-risk behavior we have the makings of a crisis. Our low-risk behavior has already created a fast immeasurable gulf in what we can do today versus what we should be doing today.

come a new battleground for national supremacy. The United States will very likely soon commit to a new program for achieving progress in computing. This program by all accounts will be focused primarily on the computing hardware first, and then the system software that directly connects to this hardware. The goal will be the creation of a new generation of supercomputers that attempt to continue the growth of computing power into the next decade, and provide a path to “exascale”. I think it is past time to ask, “do we have the right priorities?” “Is this goal important and worthy of achieving?”

come a new battleground for national supremacy. The United States will very likely soon commit to a new program for achieving progress in computing. This program by all accounts will be focused primarily on the computing hardware first, and then the system software that directly connects to this hardware. The goal will be the creation of a new generation of supercomputers that attempt to continue the growth of computing power into the next decade, and provide a path to “exascale”. I think it is past time to ask, “do we have the right priorities?” “Is this goal important and worthy of achieving?” veral types of scaling with distinctly different character. Lately the dominant scaling in computing has been associated with parallel computing performance. Originally the focus was on strong scaling, which is defined by the ability of greater computing resources to solve a problem of fixed size faster. In other words perfect strong scaling would result from solving a problem twice as fast with two CPUs than with one CPU.

veral types of scaling with distinctly different character. Lately the dominant scaling in computing has been associated with parallel computing performance. Originally the focus was on strong scaling, which is defined by the ability of greater computing resources to solve a problem of fixed size faster. In other words perfect strong scaling would result from solving a problem twice as fast with two CPUs than with one CPU.

aspects of the algorithm and it’s scaling that speak to the memory-storage needed and the complexity of the algorithm’s implementation. These themes carry on to a discussion of more esoteric computational science algorithms next.

aspects of the algorithm and it’s scaling that speak to the memory-storage needed and the complexity of the algorithm’s implementation. These themes carry on to a discussion of more esoteric computational science algorithms next.

g, and the constant gets larger as scaling gets better. Nonetheless it is easy to see that if you’re solving a billion unknowns the difference between

g, and the constant gets larger as scaling gets better. Nonetheless it is easy to see that if you’re solving a billion unknowns the difference between

The counter-point to these methods is their computational cost and complexity. The second issue is their fragility, which can be recast as their robustness or stability in the face of real problems. Still their performance gains are sufficient to amortize the costs given the vast magnitude of the accuracy gains and effective scaling.

The counter-point to these methods is their computational cost and complexity. The second issue is their fragility, which can be recast as their robustness or stability in the face of real problems. Still their performance gains are sufficient to amortize the costs given the vast magnitude of the accuracy gains and effective scaling. The last issue to touch upon is the need to make algorithms robust, which is just another word for stable. Work on stability of algorithms is simply not happening these days. Part of the consequence is a lack of progress. For example one way to view the lack of ability of multigrid to dominate numerical linear algebra is its lack of robustness (stability). The same thing holds for high-order discretizations, which are typically not as robust or stable as low order ones. As a result low-order methods dominate scientific computing. For algorithms to prosper work on stability and robustness needs to be part of the recipe.

The last issue to touch upon is the need to make algorithms robust, which is just another word for stable. Work on stability of algorithms is simply not happening these days. Part of the consequence is a lack of progress. For example one way to view the lack of ability of multigrid to dominate numerical linear algebra is its lack of robustness (stability). The same thing holds for high-order discretizations, which are typically not as robust or stable as low order ones. As a result low-order methods dominate scientific computing. For algorithms to prosper work on stability and robustness needs to be part of the recipe. urrent program is so intellectually bankrupt as to be comical, and reflects a starkly superficial thinking that ignores the sort of facts staring them directly in the face such as the evidence of commercial computing. Computing matters because of how it impacts the real world we live it. This means the applications of computing matter most of all. In the approach to computing taken today the applications are taken completely for granted, and reality is a mere afterthought.

urrent program is so intellectually bankrupt as to be comical, and reflects a starkly superficial thinking that ignores the sort of facts staring them directly in the face such as the evidence of commercial computing. Computing matters because of how it impacts the real world we live it. This means the applications of computing matter most of all. In the approach to computing taken today the applications are taken completely for granted, and reality is a mere afterthought.

We appear to be living in a golden age of progress. I’ve come increasingly to the view that this is false. We are living in an age that is enjoying the fruits of a golden age and following the inertia of a scientific golden age. The forces powering the “progress” we enjoy are not being returned to our future generations. So, what are we going to do when we run out of the gains made by our fore bearers?

We appear to be living in a golden age of progress. I’ve come increasingly to the view that this is false. We are living in an age that is enjoying the fruits of a golden age and following the inertia of a scientific golden age. The forces powering the “progress” we enjoy are not being returned to our future generations. So, what are we going to do when we run out of the gains made by our fore bearers? Progress is a tremendous bounty to all. We can all benefit from wealth, longer and healthier lives, greater knowledge and general well-being. The forces arrayed against progress are small-minded and petty. For some reason the small-minded and petty interests have swamped forces for good and beneficial efforts. Another way of saying this is the forces of the status quo are working to keep change from happening. The status quo forces are powerful and well-served by keeping things as they are. Income inequality and conservatism are closely related because progress and change favors those who benefit from change. The people at the top favor keeping things just as they are.

Progress is a tremendous bounty to all. We can all benefit from wealth, longer and healthier lives, greater knowledge and general well-being. The forces arrayed against progress are small-minded and petty. For some reason the small-minded and petty interests have swamped forces for good and beneficial efforts. Another way of saying this is the forces of the status quo are working to keep change from happening. The status quo forces are powerful and well-served by keeping things as they are. Income inequality and conservatism are closely related because progress and change favors those who benefit from change. The people at the top favor keeping things just as they are.

Most of the technology that powers today’s world was actually developed a long time ago. Today the technology is simply being brought to “market”. Technology at a commercial level has a very long lead-time. The breakthroughs in science that surrounded the effort fighting the Cold War provide the basis of most of our modern society. Cell phones, computers, cars, planes, etc. are all associated with the science done decades ago. The road to commercial success is long and today’s economic supremacy is based on yesterday’s investments.

Most of the technology that powers today’s world was actually developed a long time ago. Today the technology is simply being brought to “market”. Technology at a commercial level has a very long lead-time. The breakthroughs in science that surrounded the effort fighting the Cold War provide the basis of most of our modern society. Cell phones, computers, cars, planes, etc. are all associated with the science done decades ago. The road to commercial success is long and today’s economic supremacy is based on yesterday’s investments.

plenty there that needs to be done.

plenty there that needs to be done. t up in trying to justify the funding for the path they are already taking. The damage done to long-term progress is accumulating with each passing year. Our leadership will not put significant resources into things that pay off far into the future (what good will that do them?). We have missed a number of potentially massive breakthroughs chasing progress from computers alone. The lack of perspective and balance in the course for progress shows a stunning lack of knowledge for the history of computing. The entire strategy is remarkably bankrupt philosophically. It is playing to the lowest intellectual denominator. An analogy that does the strategy too much justice would compare this to rating cars solely on the basis of horsepower.

t up in trying to justify the funding for the path they are already taking. The damage done to long-term progress is accumulating with each passing year. Our leadership will not put significant resources into things that pay off far into the future (what good will that do them?). We have missed a number of potentially massive breakthroughs chasing progress from computers alone. The lack of perspective and balance in the course for progress shows a stunning lack of knowledge for the history of computing. The entire strategy is remarkably bankrupt philosophically. It is playing to the lowest intellectual denominator. An analogy that does the strategy too much justice would compare this to rating cars solely on the basis of horsepower. The end product of our current strategy will ultimately starve the World of an avenue for progress. Our children will be those most acutely impacted by our mistakes. Of course we could chart another path that balanced computing emphasis with algorithms, methods and models. Improvements in our grasp of physics and engineering should probably be in the driver’s seat. This would require a significant shift in the focus, but the benefits would be profound.

The end product of our current strategy will ultimately starve the World of an avenue for progress. Our children will be those most acutely impacted by our mistakes. Of course we could chart another path that balanced computing emphasis with algorithms, methods and models. Improvements in our grasp of physics and engineering should probably be in the driver’s seat. This would require a significant shift in the focus, but the benefits would be profound.